November 2016

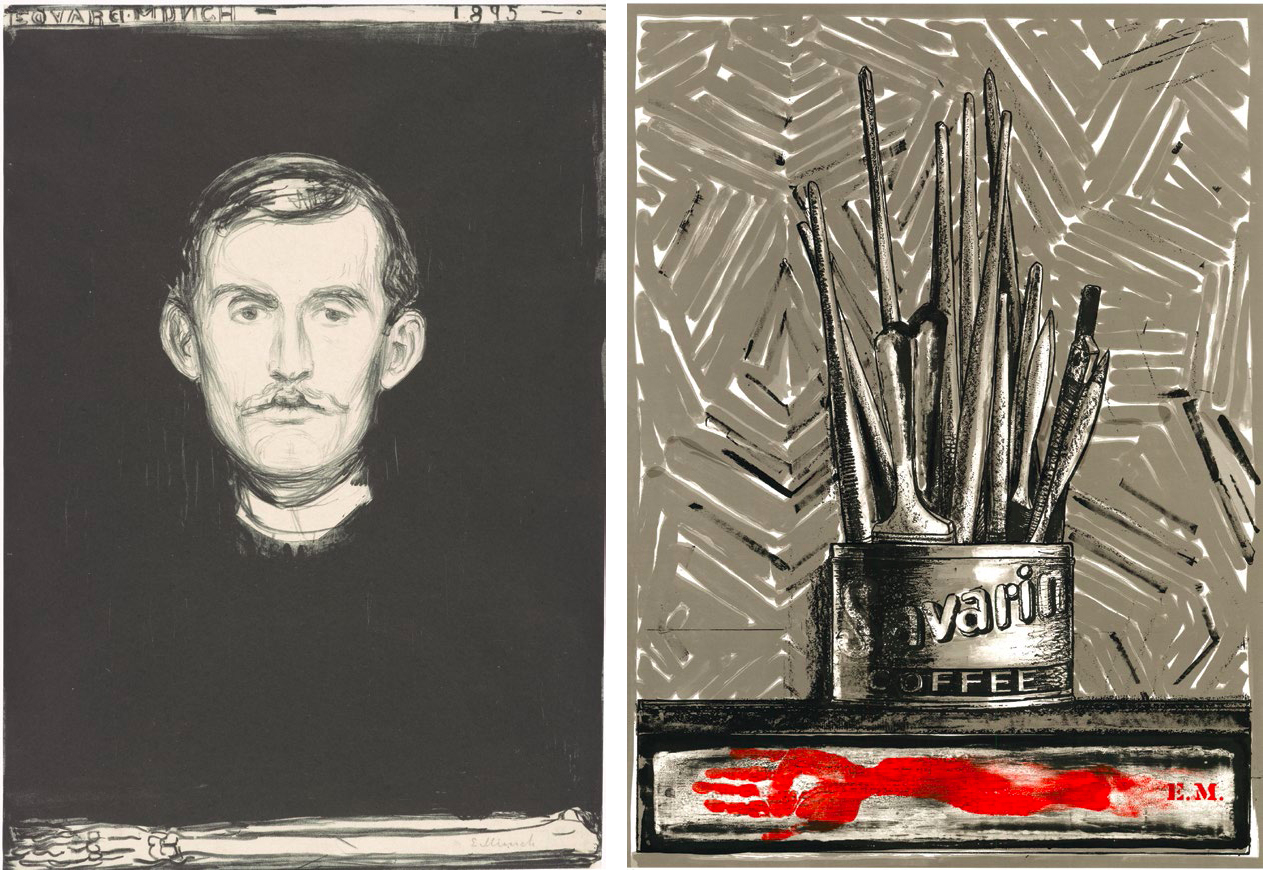

Left: Edvard Munch. Self-Portrait. 1895. Lithograph. 18 × 12½ in. Munchmuseet, Oslo.

Right: Jasper Johns. Savarin. 1981. Lithograph. 50 × 38 in. Private collection.

Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch:

Love, Loss, and the Cycle of Life

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

Opens November 12

Munch and van Gogh, Munch and Mapplethorpe, Munch and Warhol, Munch and Bjarne Melgaard: the poor guy can’t get a show of his own! In the last five years or so, the Norwegian artist — whose Scream is not his most interesting painting, and whose haunted, phantasmic prints may be his most enduring work — has played the elder figure in half a dozen two-man shows. (He was also the anchor of “Munch and Expressionism,” seen earlier this year at New York’s Neue Galerie, which put the artist alongside Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and his other German and Austrian followers.) Many of these Munch-and-after exhibitions have been co-organized by Oslo’s Munchmuseet, and though that institution naturally wants to elevate Munch’s international standing, there’s an art historical impulse at work as well. For Munch fits awkwardly into our story of the years around 1900. His eerie, often pained, sometimes dissolute imagery sticks out from the standard narrative of modernism — and it may be through his later admirers that we can best grasp his singularity.

The latest of these double-trouble exhibitions opened in Oslo this summer, when the Munchmuseet brought in a large cache of prints and paintings by Jasper Johns, the greatest headscratcher of postwar American art. (The museum is soon to move to the Norwegian capital’s flourishing Bjørvika neighborhood, which our correspondent Johanne Nordby Wernø analyzed in Even no. 3.) This month the show arrives in the United States, and like its predecessors it looks past style to unearth the influence of Munch on an artist who seems unalike at first. But Johns is a master of the quiet quotation — Leonardo, Cézanne, Duchamp, they’re all in there — and, in 1981, in the corner of a print depicting his trademark coffee can filled with paintbrushes, he stenciled the initials E.M. He had been looking at a coal-black self-portrait of Munch’s, in which the artist’s head floats above a disembodied arm. Though Johns did not quote it directly, he channeled it into the container of brushes that are his own sideways self-portrait. Munch’s signature was his own.

In the same year, Johns began a suite of three large paintings, some of the last to feature his distinctive crosshatching, all of which were entitled Between the Clock and the Bed. The linear slashes, encased in jarring complementary colors, are as cool and composed as anything Johns has painted. Look, though, at Munch’s very late Self-Portrait Between the Clock and the Bed, completed in 1943. The artist, nearly 80, stands stock-still and anxious, hands dangling from a baggy blue jacket. To his right is a grandfather clock, its face level with the artist’s own, counting down the time left until the final hour. To his left is the bed — a modest cot, one you might even confuse for a hospital berth. And the bedspread: it's crosshatched, slashed with lines of red and navy, and must have reverberated for Johns with uncanny force. (This show includes not just all three Johns paintings and the Munch they draw from, but the quilt too!) What Munch made emotional, Johns made cerebral — but the Norwegian’s weirdness is there, skulking beneath the American’s impassive surface.

Alice Neel

Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

Opens November 5

Neel’s intimate, uneasy portraits — of the poet Frank O’Hara, of artists Andy Warhol and Robert Smithson, of herself, eightysomething and nude — stand proudly askew in the history of postwar American painting. This show musters 70 of her fleshy paintings, whose funny proportions and coloring only compound their psychological acuity. Tours next year to Arles and Hamburg.

Tacita Dean

Museo Tamayo, Mexico City

Opens November 5

The British artist is at work on a new film for this exhibition, which also features her underappreciated, chalky black-and-white paintings. Dean’s dogged commitment to analog film — the number of labs that can develop her footage keeps shrinking — forms part of a greater exploration of memory and obsolescence.

11th Shanghai Biennale

Power Station of Art, Shanghai

Opens November 11

Its theme, the question “Why not ask again?”, sounds annoyingly vague at first. But this year's edition of China's oldest biennale has been curated by the Delhi-based trio Raqs Media Collective, who have promised to apply their intellectual heft and sociological bent to a number of “pressure points.” In a country where questioning is subversive, it will be interesting to see how much pressure the 92 artists can actually apply, given that the exhibitions are being held at the Power Station, a state-run space.

David Hockney

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Opens November 11

The naked boys in the pools of Beverly Hills are easy to love, but how do you feel about the later Hockney: giant, Day-Glo panoramas of Yorkshire forests, or sallow full-length portraits with seafoam backdrops? Prepare for a barrage of paintings, photos, iPad drawings, and videos: over 700 works, all from the last decade and not always on the near side of goofiness.

Oil on canvas. 38½ × 50½ in. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

The Artist’s Museum

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

Opens November 16

In this meta-examination of how art is conceptualized, produced, and exhibited, 12 artists — among them Rachel Harrison, Carol Bove, and the thoughtful Italian filmmaker Rosa Barba — take a turn as cultural historians or curators, assembling artifacts and weaving other artworks into their photographs, films, and installations. The show has been organized by the shrewd Dan Byers, who co-helmed the much admired Carnegie International in 2013.

Frédéric Bazille: The Youth of Impressionism

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Opens November 18

In an 1870 painting we see Manet, Renoir, Monet, and the writer Émile Zola in Bazille's studio; Manet himself took a brush to the painting, and added a figure of his young admirer. It was one of Bazille's last works: later that year he was shot dead on a battlefield of the Franco-Prussian War, aged just 28. This definitive retrospective of the almost-impressionist is one of the year's most important shows; it garnered raves at its first stop in Bazille's hometown of Montpellier, and tours next year to the National Gallery in Washington.

Francis Alÿs

Secession, Vienna

Opens November 18

Think of them as fables: a man pushes a block of ice through a hot city until it melts, a phalanx of students grabs shovels and moves a mountain by some infinitesimal degree. The Belgian artist is a storyteller of the everyday, and this show will feature both a new film and more than a hundred tender paintings of quotidian Mexico City that could fit in your pocket.

Samson Kambalu

NSU Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale

Opens November 23

The Malawian artist and author had a hit at the last Venice Biennale with his bogglingly complex archival study of the writer Gianfranco Sanguinetti. (The Italian situationist ended up suing Kambalu, and lost.) This first American exhibition features 12 recent films by Kambalu, screened inside a reproduction of Thomas Edison’s 19th-century production studio. His "Nyau Cinema" is also showing this month at London's Whitechapel Gallery.