Master of Fortune

by Thomas Chatterton Williams

Kerry James Marshall. Untitled (Painter). 2009. Acrylic on PVC panel.

44½ × 43 in. Museum

of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

Kehinde Wiley: Lamentation

Petit Palais, Paris

October 20, 2016 – January 15, 2017

Kerry James Marshall: Mastry

Met Breuer, New York

October 25, 2016 – January 29, 2017

“All Black Everything” was a phrase that became popular, briefly, around the release of Jay Z and Kanye West’s 2012 album Watch the Throne. A rallying cry as well as a sentiment tapping into the larger jubilation and sense of pride that the glamorous Obama presidency had sparked four years prior, it was also a tacit acknowledgment of the historical and ongoing exclusion that black people face, especially at the higher levels of American culture. It was an exuberantly aspirational response to what the Chicago-based painter Kerry James Marshall has described — via Ralph Ellison’s classic Invisible Man — as “the simultaneity of presence and absence” specific to the African-American plight. Watch the Throne, as Zadie Smith observed, “paints the world black: black bar mitzvahs, black cars, paintings of black girls in the MoMA, all black everything, as if it might be possible in a single album to peel back thousands of years of negative connotation. Black no longer the shadow or the reverse or the opposite of something but now the thing itself.” Black, in other words, as another kind of normal, but also an excellence.

That expression — all black everything — kept running through my mind as I took in two recent shows: the 61-year-old Marshall’s own glorious retrospective, “Mastry,” at the Met Breuer in Manhattan (and forthcoming in 2017 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles), and the 39-year-old Kehinde Wiley’s much smaller exhibition, “Lamentation,” at the Petit Palais in Paris. I thought about it as I passed from Léon Bonnat’s staid, ghost-white depiction of Christ on the cross, done in 1874, to confront the color and light bursting from Wiley’s hexagonal column of stained glass pseudo-religious panels. The works have an immediate visual appeal. The almost photographic realism of Wiley’s subjects’ youthful, brown-skinned bodies and faces undeniably disrupts the imperial setting in which they are displayed. So too does the more metaphorical “blackness” of their clothing and mannerisms, a defiant interrogation of the politics of respectability, as conveyed through a specific set of class signifiers — tattoos, hair weaves with red and blue highlights, gold necklaces, Air Jordans. But that disruption lasts only for a moment. With Wiley, once the novelty of the experiment wears off — “urban” black people in poses of classical European portraiture — the works, including a couple of enormous oil paintings of large figures in repose against the artist’s signature patterned backgrounds, seem oddly solipsistic. They convey stubbornly little outside of themselves: a question is posed without even the gesture of an answer. This is one kind of all black everything, but it feels like a gimmick, the aesthetic equivalent of blue ketchup.

That is not the case wandering through the immersive, phantasmagoric Marshall retrospective at the Met Breuer. Though the two artists ostensibly traffic in the same basic material of the contemporary black American social context, and though they both banish whiteness from their purview almost entirely (outside of the fact of the works’ formal inheritance — large-scale figurative painting; oil on canvas and stained glass for Wiley; acrylic, oil, and more obscure modes like egg tempera for Marshall), the effects the two are able to achieve could hardly be more different. Albert Murray, the great literary and jazz critic, once observed, “Any fool can see that the white people are not really white, and that black people are not black.” As if to emphasize the literal truth of that statement, and to articulate the sheer and willful inaccuracy of the everyday language we rely on to sort others and ourselves into abstract color categories that carry real social consequences, Marshall paints his subjects not brown, not even dark brown, but inhumanly black. His is a parallel world of bodies sheathed in licorice skin. While we have lost — if we ever had — the ability to look at brown people objectively, the appearance of actual black people destabilizes: there is the elegance of the panther on display here, and the occasional white face (rendered accurately, not as white but in flesh tones) almost looks ludicrous in comparison.

Ian Alteveer, the curator of this show’s New York iteration, staged an entire, breathtaking bay of the Met Breuer’s fourth floor with one of Marshall’s strongest series: nine historical-scale paintings of housing projects in Chicago and Los Angeles, as well as bright and cheerful suburban scenes that turn Norman Rockwell on his head. In one of the most arresting canvases, Bang (1994), a trio of jet-black children, one girl and two boys, stand in a spacious and pristine backyard replete with barbecue grill and white picket fence. The girl, with braided hair and a pink skirt, regards the boys while holding an American flag; the boys, dressed identically in white T-shirts and black-and-white Converse All Star sneakers, solemnly regard the flag, their right hands on their chests in salute. “WE ARE ONE,” reads a banner snaking beneath the children’s feet, and down there too are four pink clouds. Marshall has painted the words “HAPPY JULY 4TH” on the first three, and the last says “BANG,” an ambiguous onomatopoeia that could signify fireworks or something grimmer. This is their country, too, the painting would like to remind us; whether that country wishes to reciprocate their pledge of allegiance or not is another question.

Acrylic and collage on canvas. 8 ft. 4 in. × 11 ft. 10 in. Denver Art Museum.

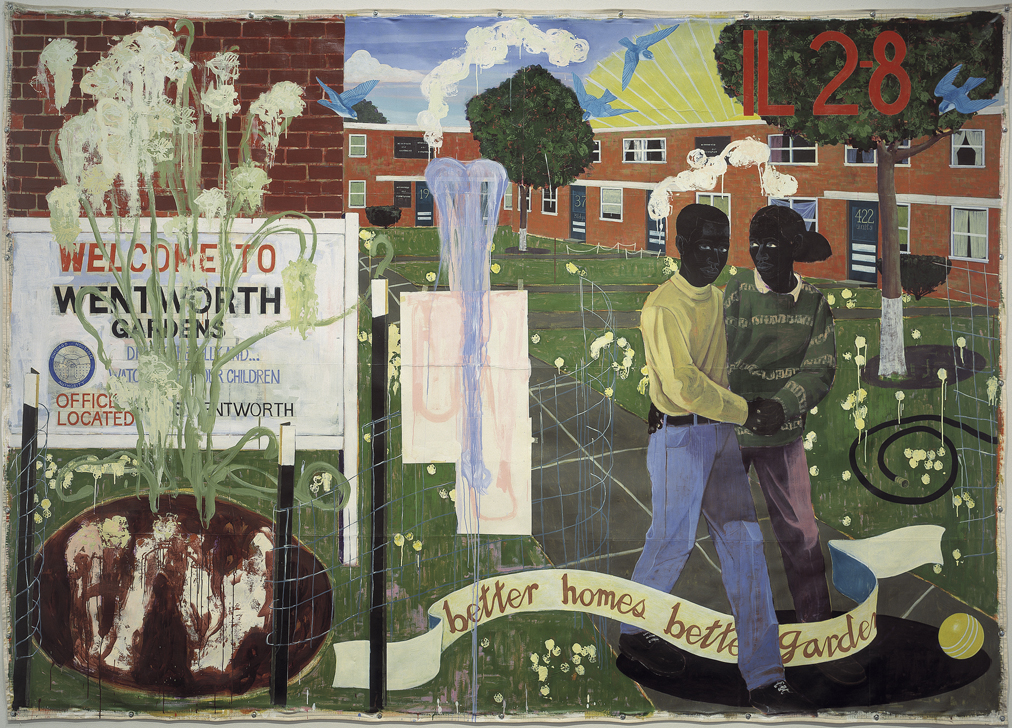

Many Mansions, also from 1994, shows three black men in pants and shoes as black as their hair and skin, pressed shirts as white as their eyes, and tie bars that glisten like the studs in their ears, beautifying the grounds around their housing project. They rake and tend to the flowerbeds that have been rejuvenated in the sunshine, two Easter baskets letting us know the season is spring. This painting complements another from the same year, titled Better Homes, Better Gardens, in which two black male teens — who might very well, in another setting, or in the eyes of another artist, be depicted as menacing — walk peacefully through the Wentworth Gardens housing project in Chicago, their hands clasped and arms draped around each other’s waists. It is a sight as tender and challenging to our assumptions of black masculinity as Barry Jenkins’s wonderful recent film Moonlight. The image’s awareness of itself as art, and specifically as painting, the illustrative flourishes rendered on top of the scene, notably the spattered yellow dots and the messily articulated flowers; and the textual elements and flatness of the landscape also bring to mind the British Pop pioneer Richard Hamilton’s landmark 1956 collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? What is it indeed?

There are many other treasures. Toward the end of the show is a series of untitled portraits from 2009 of fictional painters. One woman — her skin darker than her dark brown hair, and so black it gleams at two points on her forehead like corners of polished onyx — mixes her pigments on an enormous palette, staring out at the viewer with what can only be described as a look of sheer integrity. The same woman, on another day, labors over her self-portrait, whose canvas is ironically detailed like a paint-by-numbers composition; in another, a man does the same. These two painters then reappear in full-frontal nudity in a pair of stunning pictures, Bride of Frankenstein and Frankenstein, both from 2009. Here, the bright white points across the tops of their faces mimic the electricity that surges through Frankenstein’s monster or the stitches that sometimes appear along its forehead. The man is hunched as though he might pounce. A long, almost animal penis dangling between his thighs serves as a rebuke to the Greek and Renaissance preoccupation with minuscule genitalia as some mark of elevation. The bride, for her part, hands on hips and eyes saying she is tired and having none of it today, wears her voluptuous nakedness like a badge of honor, with all of the self-possession of Manet’s Olympia and none of the servility that both that white courtesan and her black servant necessarily embody. The woman we are watching here is no prostitute. The diamond band on her finger reminds us she is not ours.

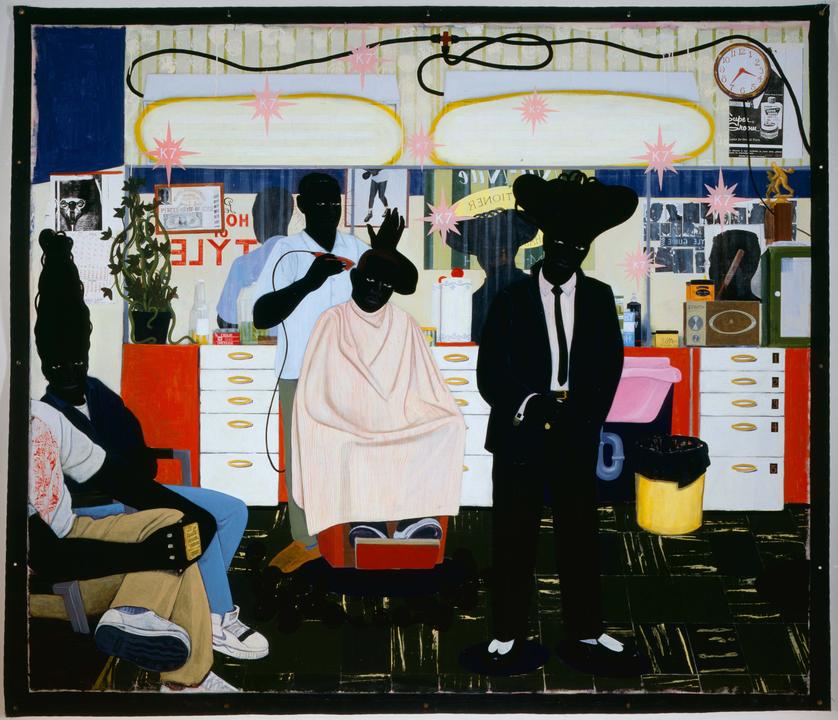

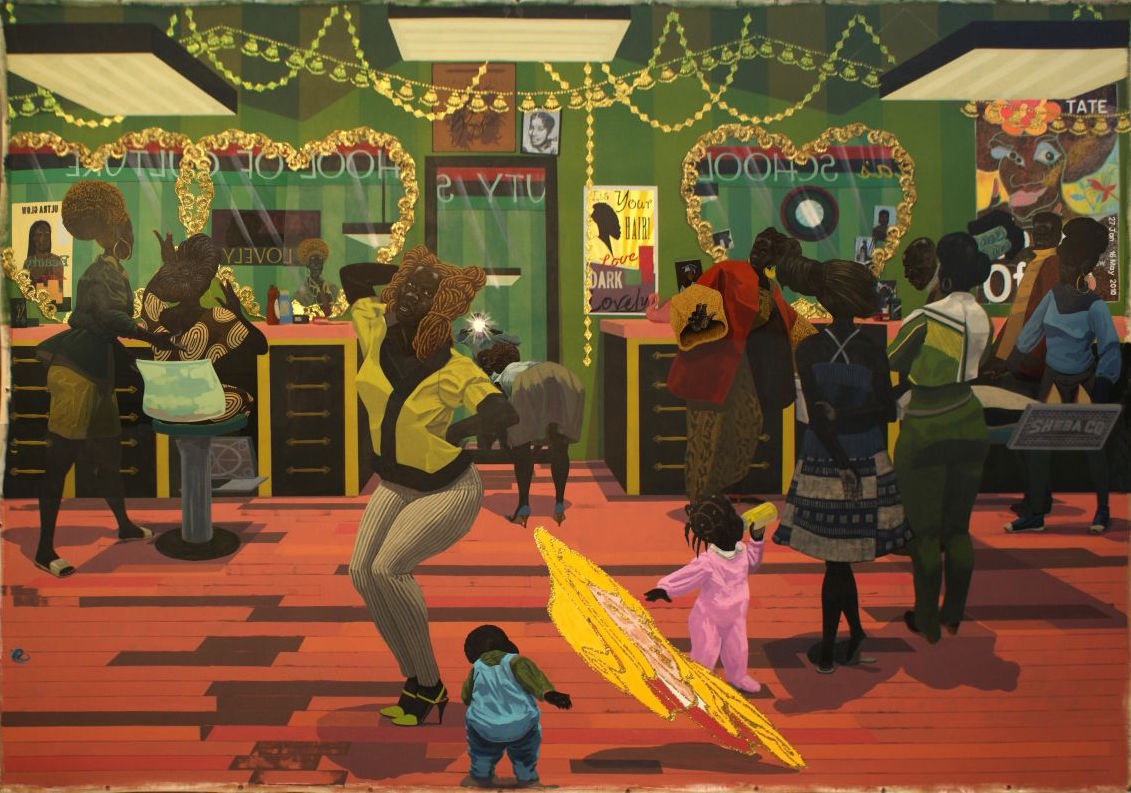

In contrast to Wiley, the longer one lingers in Marshall’s world, the less its freshness fades; the more the paintings reveal. At the Met Breuer, the tone was set by the very first painting on the third floor: his massive De Style (1993), a gorgeous barbershop scene whose title plays both on black slang and the interwar Dutch movement that strove to simplify visual compositions. Marshall restricts himself, like Mondrian and the other artists of De Stijl, to black, white and (mostly) primary colors, but he is uninterested, here or elsewhere, in abstraction. Four of the five figures that populate the room all stare straight at the viewer (the fifth’s upper body is partially outside of the picture). Their clothing mixes eras: one man is chic in black suit, white shirt, and skinny black tie, hair elaborately piled high in a crown of dreadlocks, spats on his feet. Another sports white tennis shoes and a four-finger ring of the fashion adopted by rappers in the late 1980s. But the central figure, shrouded in a peach cape, holds his head to the side, the barber’s elbow bent behind him at such an angle that, when looking from a distance, the two conjoin into what looks like a silhouette of the rapper Biggie Smalls’s iconic Kangol.

The intergenerationality and intrinsic Americanness — these are not interlopers, upstarts, or new arrivals — of the black experience manifests in numerous subtle and thought-provoking moments throughout the exhibition. Specifically, the connective tissue of music throughout the black aesthetic tradition is something Marshall harnesses, as writers like Murray and Ellison did in their literature, to complicate and deepen his engagement with the western artistic tradition. The superimposition of notes and song lyrics directly onto numerous canvases feels both obvious and ingenious. In Past Times (1997), a stunning, giant image of lakeside picnickers, Marshall evokes generational difference in the black experience through the juxtaposition of song lyrics emitting from parallel boomboxes: from one, the Temptations belt out “It was just my imagination running away with me”; from the other Snoop Dogg raps, “With my mind on my money and my money on my mind.” Both songs, of course, represent music that was embraced and even co-opted by suburban whites. But if that is of any consequence to the blacks in Past Times, they don’t let on. Instead, decked out in crisp white linen, they play croquet and golf and waterski behind motorboats, owning all of it. The scene easily rises to the scale and force of Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe or A Sunday on La Grande Jatte.

9 ft. × 13 ft. 2 in. Birmingham Museum of Art.

That’s because, beyond all of the ideas he manages to pack into an eight-by-ten-foot space, Marshall really can paint, more rigorously and ambitiously than virtually any other American in recent memory. Walking amid the 72 paintings here, spanning three and a half decades, I was reminded at times of Manet and Seurat, but also of Rembrandt and even the symbolist and primitivist Henri Rousseau, whose Sleeping Gypsy (1897) seems to lurk at the borders of Marshall’s dreamscape. It’s not coincidental; Marshall’s encyclopedic knowledge of art history suffuses his practice. Whereas Wiley’s facile interest in swapping a black mother and child for the seated Madonna and Christ amounts to little more than pastiche, Marshall announces himself as the continuation — the salvation, even — of the Western painterly tradition in its entirety. That commitment may set him at odds with many of the leading painters of the last 40 years; technical acuity has long been eliminated as a marker of quality in art, and conceptual sophistication has often gone hand in hand with an indifference to the past. But in Marshall’s case, working with the history of art does not offer a conservative evasion of the challenges posed by the readymade, conceptual art, and the rest of the modernist inheritance. On the contrary, it is at once a personal and political affirmation. The goals of these paintings can only be realized through a dialogue with older art, a dialogue in which Marshall speaks as an equal.

This self-awareness and sense of mission is firmly on display in the illuminating pendant exhibition, “Kerry James Marshall Selects,” in which the artist showcases some 40 works from the Met’s collection, ranging from the Northern Renaissance to French postimpressionism, and from African masks to mid-century American photography. (The only two living artists included are Frank Stella and Gerhard Richter — not very modest picks for colleagues on Marshall’s behalf.) This is a shrewd gambit, no, a warning, against the temptation to reduce his own vast accomplishment to one of mere identity politics or simplistic race pride in the “black is beautiful” manner. Marshall’s paintings, this show proves, can sit confidently — even superiorly — beside anything in the Met’s own holdings. “But why all the pretty icons always all white?” Jay Z raps on Watch the Throne, “Put some colored girls in the MoMA.” Marshall has done the rapper one better: he’s put himself on Mount Olympus.