Spin Cycle

by Lucy Madison

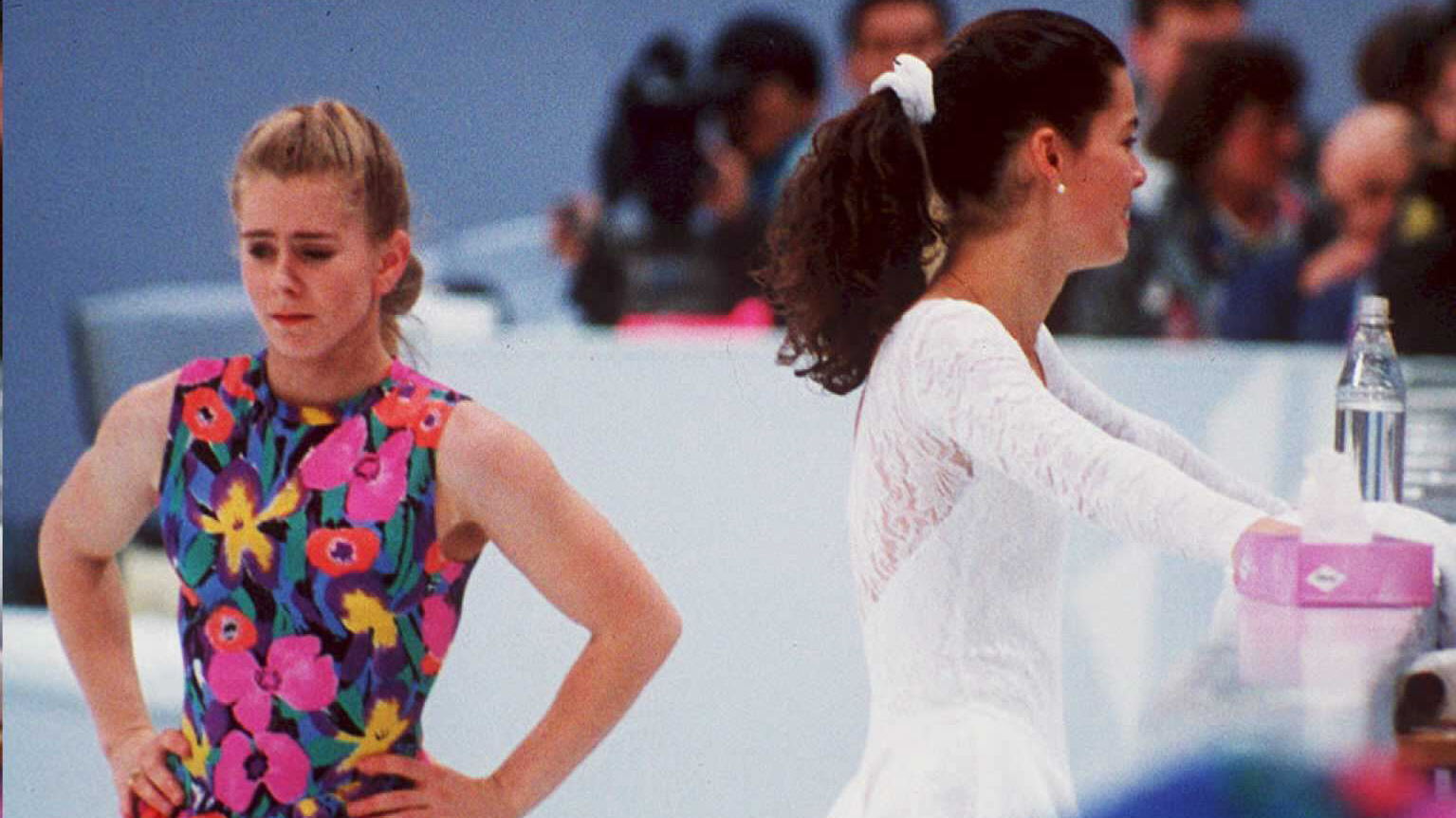

Tonya Harding is awarded the gold medal at the 1991 US Figure Skating Championships, alongside Kristi Yamaguchi (silver) and Nancy Kerrigan (bronze). Photo: Tim Defrisco.

I am a longtime Tonya Harding superfan, and I have suffered many indignities for my love. My parents looked on in mild confusion when, at age five and wearing my first pair of figure skates, I declared her my favorite athlete. My brother dubbed her “thunder thighs,” and then transferred that nickname to me. For years after Tonya’s rise to US champion and later humiliation, I was mocked by my friends for my devotion to an athlete widely reviled as graceless, classless, and criminal.

As a skater, Tonya had always been considered powerful but artistically inept. She was short and sturdy in stature, with these huge, thrilling jumps but absolutely nothing in the way of balletic extension or grace; she was looked on by the media and the skating community as trashy, mean, and definitely guilty of trying to club Nancy Kerrigan in the knee. She was the skating world’s red-headed stepchild, and, to the extent that the wider nation thought about her at all, they seemed to agree. Then, in 2014, the tides started to turn. The literary journal The Believer published a lengthy apology for the skater, and other reevaluations of Tonya’s legacy began popping up online. The filmmaker Nanette Burstein directed a riveting and sympathetic documentary called The Price of Gold, which detailed Harding’s hardscrabble background and the saga of the 1994 Olympics, after which she was banned from the sport for life. A couple of New York writers started selling $65 sweatshirts emblazoned with the phrase “No Comment,” an homage to a shirt Tonya wore back in the day. (I bought one.) My beloved black sheep was now trendy. The arc of history had been long, but it had bent toward Tonya.

This is all to say that I was excited to watch I, Tonya, the new mockumentary from director Craig Gillespie that promised a revisionist celebration of my childhood hero. The first half of the film depicts Tonya’s troubled upbringing at the hands of her abusive, alcoholic stage mother; the second recounts the comically bungled hit-job on fellow skater Nancy Kerrigan, executed by her ex-husband Jeff Gillooly and a handful of oafish accomplices. I wanted to love this movie. And for those who remember Tonya only as a one-dimensional 90s monster, perhaps the movie’s narrative does enable a slightly more complex reading of an athlete with superhuman talents and human flaws. But I found it to be a hard shell of nostalgic camp, empty on the inside but for a hint of disdain.

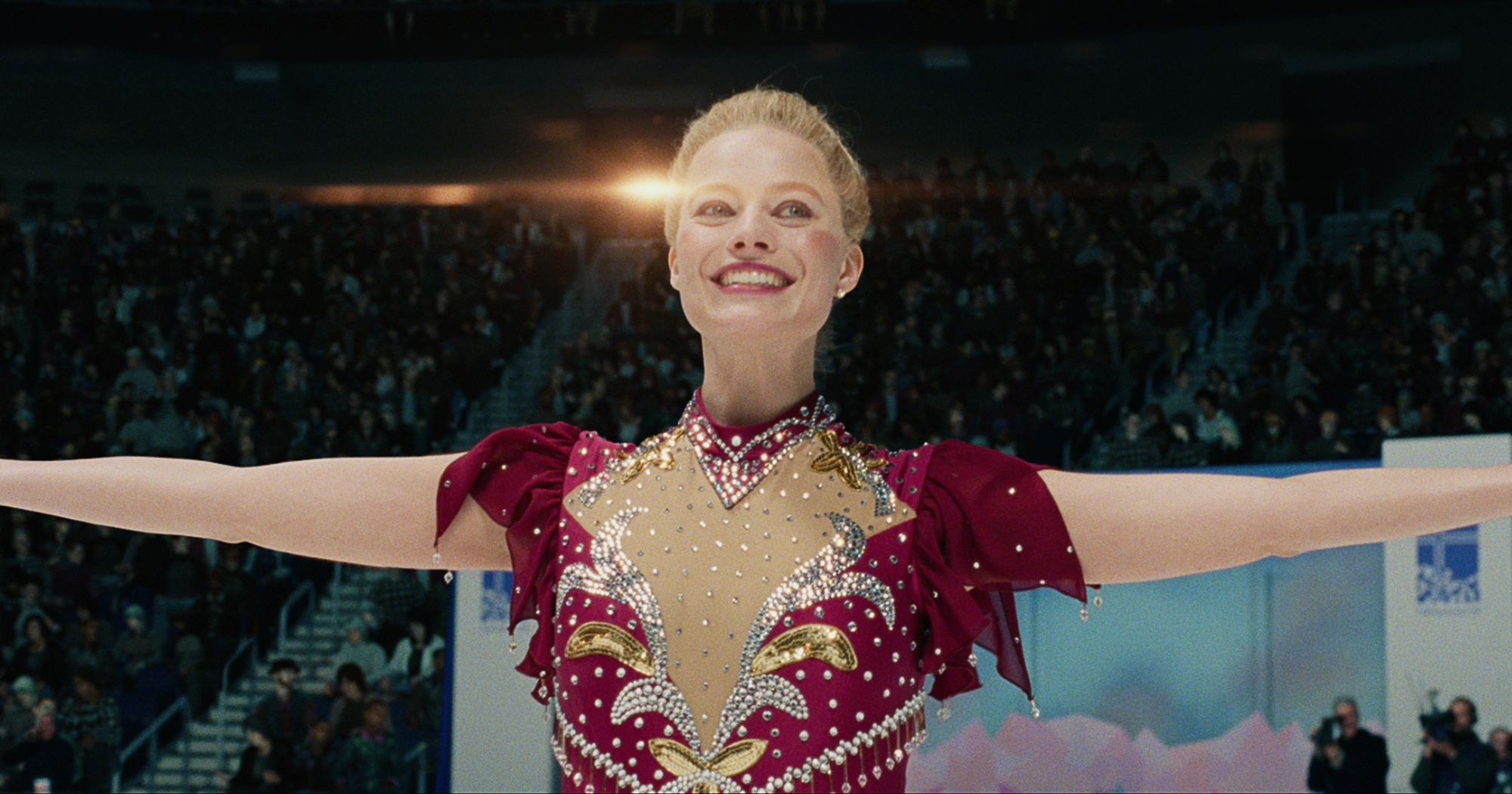

The Tonya I knew and loved, Tonya the skater, was mostly missing from I, Tonya. The Australian actor Margot Robbie does her best with the material, but her performance mirrors the confused tone of the film, which vacillates between seriousness and high camp. Only in a few sequences does Robbie show what made Tonya so winningly Tonya-ish — like the scene where she’s on an early date with Gillooly and casually corrects his inexpert attempt to fix his car. Or the montage that shows her getting into shape by rolling logs and doing the workout from Rocky. It’s those little details, too rare in Gillespie’s hollow and hard portrait, that show how Tonya was original and unexpected and, for all of her “rough edges,” kind of sweetly naïve.

We’re given any number of reasons to pity Tonya, but few to love her. Yet Tonya was tenacious and full of contradictions, and it seemed to genuinely hurt and confuse her that Americans hated her so much. She was physically powerful and came off as almost shockingly tough, but that didn’t mean she was immune to the constant criticism of her body, her hair, her “look.” (I’m reluctant to go after Robbie for her physique, but she is simply too tall, thin, and elegant to make a convincing Tonya Harding. At one point during the movie it dawned on me that the actress actually looked more like… Nancy Kerrigan.) Tonya could be lazy, reckless, and ruthlessly determined all in the stretch of a minute, which made for breathtaking television. She would fail and fail and fail again, and then, just when you thought she was finished for good, she would do something charming and spectacular, and would draw me in all over again. She was relatable, and above all she was real — which was then and remains now an anomaly in elite figure skating.

A film that evokes those contradictions much more successfully is Burstein’s The Price of Gold — a movie that was hard to stop thinking about as I watched I, Tonya, not least because Gillespie’s film feels like a derivative and lesser version of it. Tonya distinguishes itself from Gold primarily by turning up the comedy: In one scene, Tonya curses out a panel of figure skating judges while wearing a ridiculous bubble-gum-pink outfit; in another, she shoots a gun at Gillooly, then turns to the camera and snarkily denies that she shot anyone. (These straight-at-the-camera asides frequently occur during moments of domestic violence.) Whereas Burstein’s touch is deft and sensitive when it comes to Tonya’s class background and abuse by her mother and husband, Gillespie’s direction is heavy-handed and condescending: Tonya’s skating getups, hair and makeup included, are unrealistically garish, for instance, and her mom’s odd appearance and incessant smoking are played for laughs. He strives for big moments of comedy and drama without achieving much of either. Say what you will about Tonya, at least she knew how to land a tricky combination.

I was 8 years old when Tonya became the first American woman to land the triple axel in competition, and the thrill of the moment was so resonant for me that I still remember exactly where I was when it happened. As a skater I loved Tonya because, like her, I was strong and fast and artless; I loved to see her succeed because it meant I had a chance, too. On the human level, I was already aware that I wasn’t as perfect or beautiful or popular as I would like to be, and yet here was an example of an obviously flawed woman — someone who my mom would surely not have picked as my role model — still experiencing ecstatic heights of glory and success. In the movie, though, Robbie plays the triple axel scene with a sort of deranged look on her face. How cruel, in a moment I remember as so pure and joyful, to give Tonya crazy-eyes. The skater, for what it’s worth, is said to have liked the final cut of the film, and she was at the premiere, posing in pictures with Robbie; it did look like she was having fun. The media has been dining out on the story of Tonya Harding for decades. Let’s hope this time she at least got paid.