Alphabet City

by Linda Besner

I had been living in Toronto for five years when, one morning, I swung my feet out of bed and splashed into a pool of water. I admit I was less surprised than one might hope; the apartment was a clammy basement unit, gently but insistently returning to nature. Visitors from out of town politely stifled their horror, but to friends in the city, who all lived with roommates farther from the core, my crumbling bunker was a gem — C$550 (or US$450) for a one-bedroom all to myself, within walking distance of Thai food, a university library, 24-hour strawberry milkshakes, and mass transit. I knew that if I ever left the apartment, I would have to leave the city. That morning, when I moved my bed to mop up the seeping stormwater, I discovered a delicate fringe of green mold dappling the wall. I decided then to move back to Montreal.

That was in 2013; the average house in Toronto now costs a hair less than a million Canadian dollars (or US$780,000, a rise of 33% in just the past year), and dank basement studios the same size as mine (cynically marketed as “blofts”) commonly rent for a thousand dollars a month. On November 1 this year, Sidewalk Labs, a division of Alphabet (the corporate parent of Google), held a town hall meeting in downtown Toronto to discuss its recently announced and unprecedented project: an urban innovation hub that would target the city’s problems of affordability and sustainability by building a neighborhood “from the internet up.”

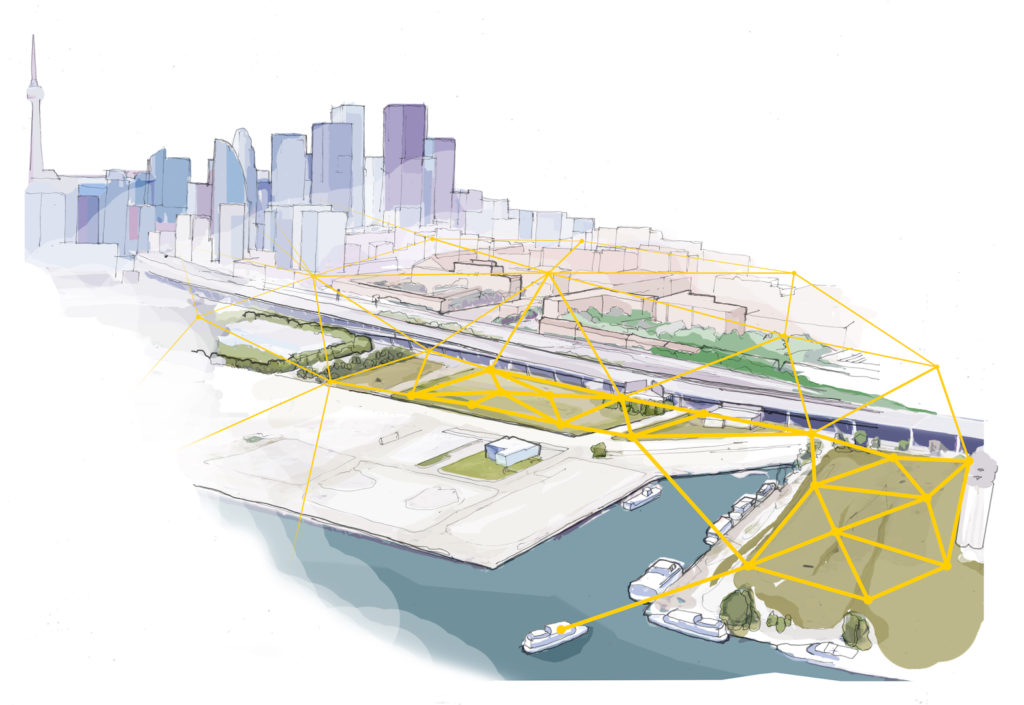

This technocratic nirvana would be situated in a 12-acre plot called Quayside, located just east of the downtown core, in the spit of post-industrial misery clamped between the deafening Gardiner Expressway and the polluted shore of Lake Ontario. Unlike recent bids by governments desperate to house Amazon’s new headquarters (Chicago offered the company a staggering billion dollars of workers’ income taxes to sweeten the deal), Quayside will receive a guaranteed US$50 million in investment from Alphabet in the next year. Moreover, if all goes well in Sidewalk Labs’ partnership with the government land-stewardship corporation that oversees waterfront development, this modest experiment will eventually be scaled up into a set of networked neighborhoods covering 33 million square feet, a city-within-a-city the size of Venice.

Recently, I walked the forlorn streets of the future Quayside. Much of Toronto’s waterfront is disfigured by luxury condos, and Quayside is skirted by immense towers like parked cruise ships. I browsed a parking lot of flattened trash: jumbo Tim Horton’s cups, cans of Canada Dry ginger ale. Pressed against a chain link fence, a few stunted trees whined like dogs. The CN Tower’s needle of nostalgic futurism blinked to the west. At the east end of the plot loomed the Ozymandian bulk of an abandoned soybean silo that Sidewalk plans to transform into an art gallery, hotel, urban farm, or garden — an iconic landmark that honors the lakefront’s industrial past while firmly laying it to rest.

The 200-page vision document, folksily doodled with seagulls and firefighters, tells us that the anticipated Googlehood would comprise “physical, digital, and sense” layers. The physical and digital layers are as you would expect: Google headquarters flanked by “radical mixed-use” Lego-like modular housing and self-driving shuttles, as well as a programmable interface that would allow app developers access to the neighborhood’s data and infrastructure. The sense layer, however, would deploy wall-to-wall sensors and cameras to capture the flow of pedestrian, bicycle, and vehicle traffic, as well as environmental measures like hyperlocal weather patterns, carbon monoxide levels, and noise pollution. Quayside would be “the most measurable community in the world.” This is the real, unstated master plan: to build an experimental city that is also a vast real-time data-harvesting center.

At the town hall meeting, David Doctoroff, the CEO of Sidewalk Labs, assured the crowd of 900 (another thousand couldn’t get seats), “We don’t care about trying cool stuff. We care about finding ways to improve people’s lives. That’s what this is about.” It’s hard to imagine a more disingenuous statement. What about Sidewalk’s plans for, say, personal gondolas winging over the lake, underground passages for robot freight carriers, heated bike lanes to melt snow for year-round cycling, and the “next-gen bazaar” that could change daily? There is no question that Alphabet, and Torontonians, care about the cool stuff — that’s the appeal of a city designed by technologists. But along the spectrum of innovation and efficiency, how will data generated by this neighborhood be owned and used, how will privacy be protected, and how can Toronto stay in control of this relationship?

The guiding metaphor Sidewalk Labs uses is the city as smartphone. The relevant qualities would be instantaneity and constant upgrading — its developers could discard a city’s past as easily as they could create a newer, better version of its present. This idea is an attractive one to current generations conditioned to the permanent novelty and interactivity of the internet, where the slow and static evolution of cities may have come to feel counterintuitive and even withholding. But in presuming the city to be simply an object we can retool and design to our own needs, anything that doesn’t match Alphabet’s metrics of a good life would necessarily be squeezed out. To no small degree, this means the loss of pathos — what happens to the unsuccessful, the ramshackle, the ruined? This idealization of human perfectibility raises specters of infamous “solutions” of the 20th century.

Representatives of Sidewalk Labs say they want to make Torontonians safer, healthier, and richer — how could the city say no? But the problem of unsustainable and unaffordable urban centers is not the result of insufficient technical innovation; it’s the result of deeply embedded structural inequalities from which companies like Alphabet benefit. Does job loss from automation factor into their vision of the future? And what about the climbing housing prices? The population of the downtown core is projected to double by 2041; people living in thousand-dollar basements will be trapped by increased demand, and artists and culture workers will be pushed farther from the center of the city (many have already decamped to neighboring Hamilton or Guelph). Yet low-wage earners rely on the collective use of Google products as much as anyone else — and whether we trust them as urbanists or not, our cities have already been remade by Google Maps and Waze, our businesses by AdWords, our local media by Google News, our romances by Gchat. With the important behavioral insights Alphabet is poised to gain in Toronto, it will consolidate its power to help or hurt us.