The Beat of Dissent

by Chloé Buire

No city has a music scene like Luanda, where rappers risk jail to rhyme against the regime. Up all night in the most expensive city on earth

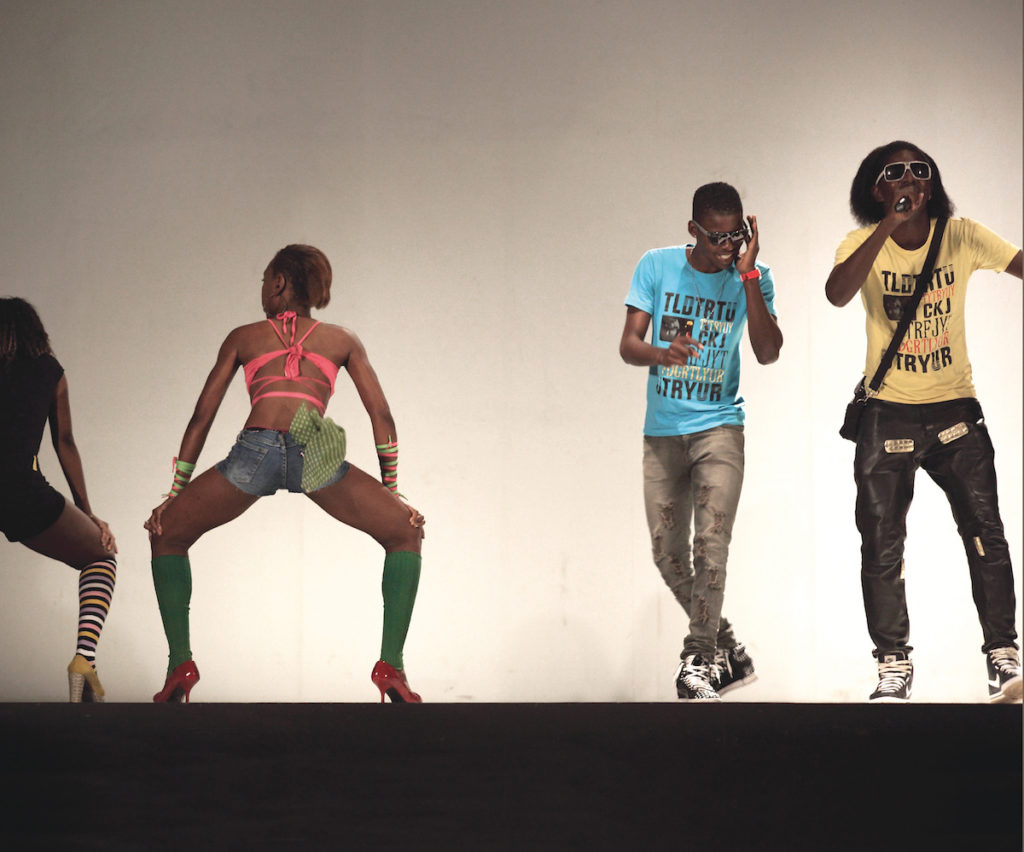

At a concert by the rapper MCK. Luanda, Angola. 2015.

This essay appeared in Even no. 6, published in February 2017. On August 23, 2017, José Eduardo dos Santos is set to step down as president after 38 years in power.

I.

June 2009. I arrived in Luanda just a week ago, and I’m exhausted. Busy roads, busy crowds, busy city. Heat, sweat, dust. Tonight, my friend Janguinda has offered to take me and an American girl I just met to an underground hip-hop concert, and I have no idea what to expect. Whatever it is, it sounds much more exciting than going to Ilha, the spit of land that encloses Luanda Bay, with its overpriced clubs catering to expats with large expense accounts. Luanda is frequently cited as having the highest cost of living in the world — a two-bedroom apartment might run you $5,000 a month — but most of its citizens live below the poverty line. The capital of oil-slicked Angola is a wildly unequal place, and outside the swankier neighborhoods is a different sort of nightlife.

As we push through the capital, I discover a new, nocturnal face of Luanda. The city of 6.5 million is as hectic as it is in daytime, but now everything holds a sense of mystery. I wonder about this underground concert. Are we going to end up in a basement in an unfinished colonial building, the sort you see in war photography? Are we going to cross paths with drug lords trading guns and illegal diamonds, like those African villains of Hollywood films? We pull into an informal parking spot, and I eventually let the Dark Continent stereotypes pass and look up. Tall buildings rise around us. The light shining down from the flats composes a neon mosaic that compensates for the lack of streetlights. We enter the club — it’s no dodgy basement, but an open-air space. The sign above the door indicates it’s a social club of sorts, an old colonial neighborhood organization. Inside are a few plastic tables and chairs and crude fluorescent lighting. Ice-cold beers are served in a corner. The American girl and I are the only white people in the crowd, and two of just a handful of women.

On stage, young men are testing the sound system: “Check, check, check. One, two. Tss, tss.” It’s quite obvious that they are not professional staff; these are tonight’s rappers, setting up for the gig. The sound check serves as a warm up; they’re adjusting their outfits, rehearsing their entry onstage. We are far from the mega-shows sponsored by Unitel, Angola’s top cellphone company, or Cuca, the national brewery, whose marketing can be seen on billboards across the capital and heard on every radio station.

The entry fee tonight of 1,000 kwanzas — the equivalent of 10 US dollars — is not cheap in a country where the majority lives on less than $2 a day. But it means that the hundred or so Angolans in attendance at tonight’s concert are aficionados. Tonight is an open-mic session, and a young MC who introduces the artists encourages the public to cheer louder. The rappers are men in their early 20s; their clothes and body language pay tribute to American rap, but they perform in Portuguese, with only a chorus or a punchline in English every now and then.

My Portuguese isn’t strong enough yet to follow their rapid flow, so I rely on the audience’s enthusiasm to judge the performances. With the help of Janguinda’s translation, I learn that Angola’s hip-hop heads are unimpressed by performers who imitate American rap wholesale, and the rhymes that win the crowd’s approval are those commenting on the quotidian details of life in Luanda. I recognize some key words of local slang. Musseques: the unplanned neighborhoods that developed spontaneously around the colonial center. Candongueiros: the ubiquitous blue-and-white minibuses that serve as public transport. Zungueiras and zungueiros: street vendors, selling everything from fresh fruit to DVDs. Luz e água: electricity and water, basic amenities affected by daily cuts.

I’ve been back to Luanda many times since that evening in the southern winter of 2009. (I ended up on stage that night with several rappers, after unexpectedly winning an album giveaway.) I’ve lived there for as long as my visas would allow, conducting research in both the city center and the sprawling self-built neighborhoods on the periphery. I’ve taken road trips across other Angolan provinces as well. And much of what fascinates me about the country now was already present that first night in the club: the invigorating celebrations by night that allay the hardships of the day, the inexplicable feeling of intimacy in one of the most crowded metropolises I’ve ever been to, and the multiple meanings of underground.

But what I didn’t know, when I went to that first concert with Janguinda, was that underground hip-hop would soon become the flashpoint for national disputes about democracy, corruption, and the future of Angola. Independent hip-hop artists such as MCK and Ikonoklasta have made no secret of their hatred of the country’s kleptocratic government, run since 1979 by President José Eduardo dos Santos, under whose watch Angola has become one of the most corrupt countries on the planet. And as the economic boom of the years after the civil war has faded, conflicts between the regime and its rappers have grown even more scathing — leading all the way to prison, in Ikonoklasta’s case. What does it mean, finally, to be underground for rappers in Luanda? And how did a bunch of hip-hop artists become the most powerful antagonists of the second-longest-serving leader in Africa?

II.

For African historians, modern Angola is a paradigmatic example of a country born out of conflict and violence. The grand colonial dream from the 1930s to 1950s, which sought to transform Luanda into “the jewel of the Portuguese overseas empire,” imposed a stark segregation between the city center, which was reserved for Europeans, and its musseques, inhabited by those who were then called “indigenes.” In 1961, a rebellion that erupted on cotton farms in the north of the country soon turned into an armed conflict in the hinterland. Anticolonial ideologies rapidly spread into the musseques surrounding the capital. Despite pitiless repression by Portuguese secret police, Luanda became the center of Angola’s national liberation struggle.

Anticolonial movements found that one of the best ways to diffuse their ideology amongst urban masses, many of whom were illiterate, was through music. From clandestine radio shows to dance clubs, from parties organized in the musseques to LPs recorded in Lisbon, a new music scene emerged that not only celebrated a properly Angolan way of life in the city — what locals call angolanidade, or “Angolanness” — but also raised political expectations for the country’s poor. The historian Marissa Moorman, in her fantastic book Intonations, quotes one artist from that time: “We didn’t play music because we were political, no, but because we lived that reality.... So we sang about our bitterness in Kimbundu, and they [the Portuguese] didn’t know. We even talked badly about them and they didn’t know it!” Many songs between 1961 and 1975 indeed became anticolonial anthems. One only has to listen to the hits “Ngongo Jami” (“My Suffering”) and “Muxima” (“Heart”) by the band Ngola Ritmos to hear the incredible power of this music that, in Moorman’s words, “makes disgrace danceable.” Even today, the music of Carlos Lamartine, Urbano de Castro, David Zé, or Artur Nunes is recognized as the golden age of Angolan music.

It was not always easy for those revolutionary, anticolonial singers and songwriters. Before independence in 1975, Portuguese colonial censors worked hand in hand with a network of Angolan informants in the musseques. At the time, the decision to go “underground” was a matter of life or death. Musicians who were not able to hide their anticolonial sympathies were deported or sentenced to forced labor. Modern urban music in Angola is thus characterized by a dual relationship to power. It was an emancipatory medium, and offered opportunities to raise consciousness and contest colonial rule. But it has also been riven from the start by paranoia and self-censorship — and that tension only increased after independence.

Angola’s independence struggle, of course, took place against the backdrop of the Cold War, and global superpowers instrumentalized liberation movements for their own ends. The proclamation of independence on November 11, 1975, marked the beginning of a long, dogged proxy war. Luanda, in the years after the end of colonialism, was controlled by the MPLA: the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, which received military support from the Soviet Union and Cuba. The interior of the country was under the control of the UNITA: the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, a guerrilla-led movement carrying American weapons and backed by troops from apartheid South Africa. The civil war lasted until 2002, fed by illegal trading in oil and diamonds.

On May 27, 1977, internal ideological divisions within the socialist MPLA led to an attempted coup against Agostinho Neto, Angola’s first president. What followed was a radical purge. Until today the number of people who were arrested, tortured, and executed remains unknown. If the figure of 15,000 victims advanced by some researchers is controversial, the social consequences of this deadly episode are widely accepted: the “27th of May” marks the beginning of a profound culture of fear.

The purge did not only target politicians who disagreed with the leadership of the MPLA, however. Popular singers from the 60s and 70s were also eliminated. The disturbing continuity between colonial censorship and the imposition of this new socialist orthodoxy sent a blunt message to Angolan artists: you are either with us or against us. Moorman speaks of a veritable “hiatus” in the history of Luanda’s music industry after 1977. From then on, musicians had to play by the rules of the propaganda machine, or else go into exile. Independent music went dormant, at least until the fall of the Berlin Wall forced the regime to abandon socialism and to accept a multi-party system.

III.

The post-socialist conversion of the Angolan regime in the 1990s opened doors for a new global exchange. Luanda’s music industry, so constrained during the one-party era, exploded with new sounds. As importing equipment became easier, electronic mixes grew more audacious; classic African rhythms met techno beats. Inspired by international hip-hop, singers developed new flows; dancers improvised new moves. This new generation’s globally inflected music was more energetic than the melodic songs of their parents, and less predictable than the norms imposed by Angolan propaganda. The new sound of Luanda gave itself a provocative name: kuduro, which literally means “hard ass” in Portuguese.

Kuduro’s main characteristic is its exaggeration. Vocals are not sung so much as shouted: aggressively, some would say, or playfully, as kuduristas would probably argue. Heavy bass lines thump at a standard 140 beats per minute. And the dance moves that are the veritable signature of kuduro are a collection of extraordinary, disarticulated moves: legs are kicking, squatting, spinning, all at once! Even the faces of the dancers are part of the improvisation. Kuduristas, whether on stage or in music videos, roll their eyes and stick out their tongues, transforming choreography into dramatic performances.

At first, kuduro mixes were recorded in backyard studios. Cassettes were sold on the street and mostly played in the candongueiros snaking their way through Luanda’s traffic. But it didn’t take long for the incredible sound of kuduro to travel internationally, thanks to emblematic figures such as DJ Amado or the Angolan-Portuguese group Buraka Som Sistema, whose 2008 song “Sound of Kuduro” features a guest verse from M.I.A. (Kuduro even traveled to the United States, where the Puerto Rican singer Don Omar earned a five-times-platinum megahit with “Danza Kuduro,” 2011’s unavoidable song of the summer, which flitted between kuduro and reggaetón.) Internationally, this music has emblematized Angolan renewal, especially after the end of the civil war in 2002. Domestically, it signaled the formation of a new cultural scene in Luanda. “The emergence of kuduro,” explains the Angolan anthropologist António Tomás, “was an integral part of reconfiguring Angolan society, positing itself as an alternative infrastructure, utterly distinct from the state media.” After years of silencing, Angolan musicians seemed to be able to craft a new form of cultural sovereignty once again.

However, the potential of kuduro to mobilize large urban constituencies has not gone unnoticed by the dos Santos regime. Despite the abandonment of socialism in the 1990s, the MPLA’s paranoid need to control the masses has not diminished. Political scientists speak of an “authoritarian reconversion” in Angola, and while the MPLA has accepted formal competition at the polls, in practice no opposition party has the means to defeat it. Private press, universities, and NGOs do exist, but most civil society funds actually come from MPLA allies who carefully choose the initiatives they want to support. The MPLA has effectively retained total control over the state apparatus since the end of the civil war, but it has needed a new source of legitimacy — and instead of blunt propaganda, now anarchic kuduro helps dos Santos consolidate his domination of Angolan politics.

The association of local MPLA figures with kuduro artists over the last few years has proven to be a handy tool of political engineering. In Sambizanga, for example, one of Luanda’s largest musseques, the party has campaigned alongside one of the neighborhood’s local heroes: the (in)famous kudurista Nagrelha, who is known for his provocative abuse of alcohol and marijuana on stage. The association of the MPLA, with its old-fashioned mottos — “The MPLA is the people! The people are the MPLA!” — and Nagrelha, the bad boy of Sambizanga, has inspired no shortage of jokes in Luanda. But no one can dispute the success of this odd couple: the party gets locals from the musseque to come to its rallies, and Nagrelha gets precious allies in the political elite. These connections not only come with expensive gifts (cars, houses, invitations to the biggest parties in town); they also allow MPLA-approved artists the support of powerful music promoters. In Angola, like in any other oligarchic regime, you make friends with the ruling party to sustain your follies, and that is as true of music as it is of the businesses more native to corruption, such as oil exploration, property development, and import-export.

In the early years of independence, influential musicians were seen as threats and eliminated. Thirty years later, the MPLA now has the means to ensure that popular idols work for the establishment, even when everything about them evokes the underground. And with the explosion of kuduro, this strategic cultural marketing has reached international shores. In 2012, a multimedia project called Os Kuduristas appeared in several major global musical establishments, including La Villette in Paris and the Transformatorhuis in Amsterdam. The project was helmed by the music company Da Banda — whose owner, Coréon Dú, just happens to be one of President dos Santos’s sons. For Moorman, the objective is clear: “Da Banda puts kuduro on display to rebrand Angola as about something other than war, conflict, oil, and corruption...to make them lovable internationally.” The branding also works internally. In Luanda, Coréon Dú created the label I Love Kuduro, supported by the Ministry of Culture and relayed on national television. (One of the public networks was, until recently, managed by his sister Isabel dos Santos — reputed to be the richest woman in Africa, with a net worth of $3 billion.) The label has turned into a veritable campaign to certify “authentic” kuduro. With I Love Kuduro, the son of the president poses as the ultimate judge of what qualifies as popular music. It is an extreme example, though hardly the only one, of how the president’s clique seeks to control life in Luanda.

The international success of kuduro undoubtedly rests upon its energetic sound and prodigious dance moves. It evokes a spirit of rebellion, victory over war and privation, the reinvention of the African body, a cynical celebration of bling and consumerism. But if we look more pragmatically at the economy of kuduro in Luanda, it is clear that we are dealing with a cultural industry under political control. Not only do the artists themselves still live in a culture of fear inherited from the 60s and 70s; more than that, the regime can now neutralize mass dissidence by deploying popular idols for their own ends. (Fans of Nagrelha, for one, did not hesitate to wear the colors of the ruling party in order to enter free concerts during the electoral campaign in 2012.) Why should they even bother with antagonistic politics, anyway? The youth of Luanda have to be pragmatic, and avoid questioning a situation established long before they were even born.

IV.

Aspiring artists have no option but to submit to the elite clique that distributes licenses for open-air shows, annual festivals, and other mainstream events. Those who make their diverging opinions known too vehemently are barred from these formal stages. They end up performing in backyard festivals organized in the musseques... or on the neon-lit stage of a small social club outside the city center. By default, they constitute the underground of the new millennium.

In search of some recognition, this alternative music scene gave itself a name: rap de intervenção social, or “rap of social intervention,” which expressed its clear objective to deliver a social and politically conscious message. Formally, this underground hip-hop circulates in the same way that the first mixes of kuduro passed through Luanda, via DIY compilations sold in informal markets. Candongueiro drivers, who are the true DJs of Luanda’s soundscape, let the engaged lyrics blast out along their routes, from the remotest musseques to the street that runs by the presidential palace — though they are careful to lower the music’s volume in the presence of traffic police. Everyone remembers the fate of the young man who was idly washing a car, humming anti-establishment lyrics, and who was overheard by members of the presidential guard. They took him to a beach nearby and drowned him in the Atlantic.

That murder took place in 2003, and the song in question was written by MCK, a skinny, bespectacled rapper with a philosophy degree. In recent years, MCK has become the figurehead of rap de intervenção. His lyrics explicitly call for the political awakening of his listeners. “Open your eyes, brother, switch off the television / tear the newspaper up and analyze your daily life,” goes the chorus of his 2002 hit “A téknika, as kausas e as konsekuências” — the song the tragic car-washer was singing before he was drowned. MCK also denounces Angola’s shuddering inequality and political corruption. His 2011 song “O país do Pai Banana” deplores that “the disparity is huge / We are stuck in this trap / Condemned to be slaves of three families.” MCK is particularly renowned for his ironic comments on the absurd details that make daily life in Luanda unique, but also so challenging. Recent hits include a song mocking the new middle-class suburbs; another one defends natural afro hairstyles against the norms of “good taste” circulating in Luanda. “They offered me $500,000 to stop rapping,” MCK told the Economist in 2012, when asked about the government’s attempts to silence him. “Now they know it won’t work.”

If MCK enjoys an almost mythical aura amongst fans of Angolan hip-hop, he is not the only rapper denouncing the abuses of the regime. Names such as Ikonoklasta, Brigadeiro 10 Pacotes, Phay Grande o Poeta, and Kid MC constitute an ever-growing group of popular hip-hop artists not afraid to attack the ruling party and its president directly. Ikonoklasta, in particular, is a young activist whose songs remix old anticolonial hymns, and since 2011, he has helped organize protests in Luanda inspired by the Arab Spring. He has witnessed both the enthusiasm of a burgeoning social movement and its violent suppression by the police. In fact, no more than a hundred participants attended each protest, but in 2012 Ikonoklasta had good reason to be optimistic — not since the purge of 1977 had dissident voices reached such a wide audience. Hip-hop had helped spread social critique beyond a limited circle of political opponents and intellectuals, and in recent years a sequence of protests has rippled through Angola. Veterans of the civil war took to the streets to claim their unpaid pensions. In several provinces, teachers went on strike. Each time, the regime has responded in flamboyant, authoritarian style, dispatching armed police to quell the teachers, siccing dogs on demonstrating students, and even assassinating two leaders of the veterans’ movement.

Ikonoklasta himself has been arrested many times, received anonymous death threats, and been beaten up in various police stations. But on June 20, 2015, the rebellious rapper became an iconic face of the struggle for freedom and democracy in Angola. He and a dozen other young men had arranged to meet at a Luanda bookstore, where they planned to discuss the ideas of Gene Sharp, an American essayist whose writing on pacifist resistance has fed social movements around the globe for decades. The police claimed that the rappers, university students, and teachers were in fact preparing a coup. The men were immediately charged with rebellion and kept in solitary confinement, without access to lawyers. This time, Ikonoklasta and his acquaintances quickly realized that they were risking much more severe punishment than a beating at the police station.

Then: human rights organizations call on the government to release the rapper and his colleagues, whom they refer to as the Luanda Book Club. To no avail. According to the law, they cannot be held without trial past September. But September comes, and they are not released. The rapper and his companions start a hunger strike — and now the affair explodes internationally. Ikonoklasta remains on hunger strike for 36 days, one day for each year President dos Santos has been in power. The image of his emaciated face races across social media, and a new wave of protests erupts, from vigils at the door of Angolan churches to concerts held in support of the political prisoners in Lisbon, Paris, and London.

The regime seems to bend under the pressure. Ikonokolasta and his colleagues are put under house arrest, and the men go home just before Christmas. But the sentence is eventually pronounced in March 2016: the 15 most infamous political prisoners in Angola are convicted of “preparatory acts aiming at a rebellion,” and sentenced to two to eight years in prison. Ikonoklasta returns to jail, and on the streets of Luanda, the mobilization for justice loses steam. People start to lose hope, especially as a financial crisis, set off by depressed oil prices, begins to bite.

This is not the end of the story, however. General elections have been announced for 2017 — and President dos Santos, after nearly four decades in power, is not contesting them. Once again, the MPLA will seek to regain its legitimacy, but the varnish of democratization of the last few years has already been erased. Just last June, a new move agitated the judicial chessboard: Angola’s Supreme Court ordered the liberation of Ikonoklasta and the other activists. The government has promised a general amnesty that might well put a definitive end to the dirty affair of the Book Club.

It took only a few weeks before Ikonoklasta decided to go back on stage with his old friend MCK. In October 2016, their new show, entitled Ikopongo — “Resistance” — was ready. But the pair struggled to find a concert hall that would take the political risk to host them. The downtown venue Chá de Caxinde eventually agreed, and the concert was slated for November 5, a day after Angola’s independence celebration. But just a few days before the show, the organizers canceled the event, allegedly after receiving “instructions from above.” This new political publicity — Amnesty International denounced the concert’s cancellation as “state censorship” — offered the rappers an ironic sort of strength. Ikonoklasta and MCK managed to convince another concert hall, one located even further from the city center, to host them on November 6. Yet when they showed up to play, they found the doors locked. So on the night of November 6, MCK and Ikonoklasta found themselves streaming their jovial, engaged rap de intervenção social from a tiny room in Zango, one of Luanda’s most remote bairros — and directly out to the limitless, global reach of YouTube. Underground hip-hop is not dead.