Black Squares

by Philip Tinari

David Diao. Glissement. 1984. Acrylic on canvas. 70 × 100 in.

In 1984 David Diao made his breakthrough painting, Glissement. Its red and white quadrilateral planes, floating somewhere beyond flatness, freely rehash the rectangular contours of the canvases that hung in the corner of a Petrograd salon where Malevich mounted his 1915 exhibition-as-manifesto, announcing Suprematism and leaving behind a single photograph. For several years before Glissement, Diao had painted nothing; the stock explanation is that he’d grown paralyzed in New York looking for new ways forward with abstraction, though the real story may be the psychological implications of returning home to Chengdu in 1979 after fleeing thirty years earlier. Malevich was a liberation.

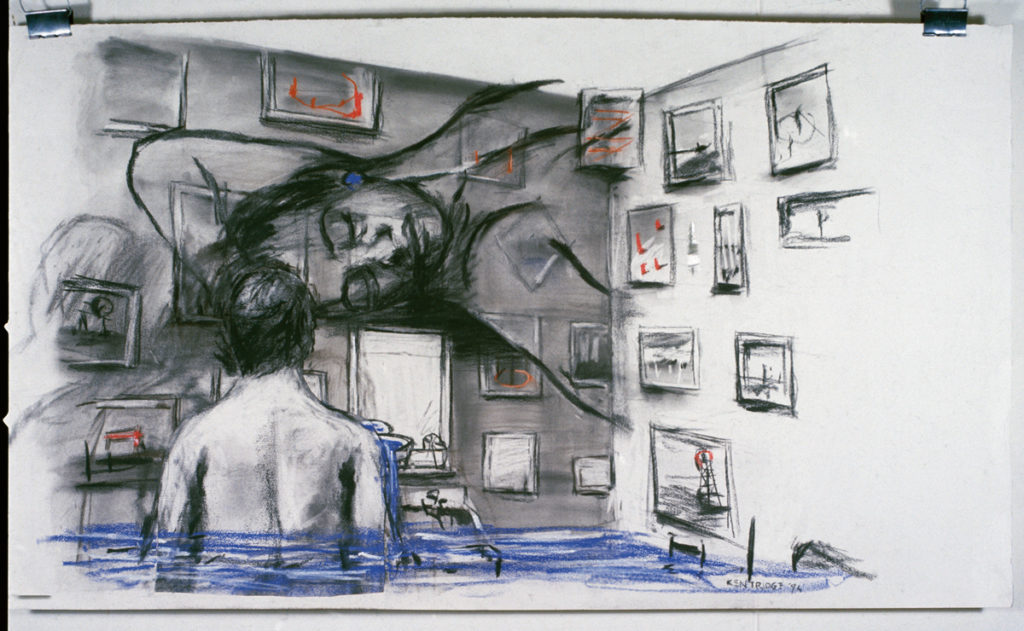

Ten years later, in Johannesburg, William Kentridge created the fifth of his “drawings for projection,” Felix in Exile. The vaguely Duchampian wordplay of the title inoculates it from the simple narratives of memory, injustice, and historical transition into which it, like a lot of Kentridge’s work, has been so often and crudely enlisted. 1994 was the year of South Africa’s first free elections, the end of the apartheid order that had, among other unspeakably worse offenses, isolated his nation in a way that afforded him the chance to embrace figuration long after it had fallen away most everywhere else. At one key moment in the film, Felix wakes up in a hotel room filling with blue pencil water, in one of the series’s rare injections of color. Felix is seen from behind, staring into a corner where drawings evoking the Sharpeville massacre hang in the same configuration Malevich employed in his “0.10” exhibition.

For both artists, with whom I spent the better part of the last year making back-to-back retrospectives at the museum I direct in Beijing, that moment of Malevich’s aesthetic manifesto — the eruption before the inevitable hardening into orthodoxy and factionalism — means the world. A romance with its uneventuated could-haves, an appreciation of its graphic sensibility, and an enduring fascination with the entropy that inevitably undoes even the most tightly wound movement bind them at a level even deeper than their shared consciousness of how things might have ended if, for example, Diao had been out shopping with Mom when the last missionary plane flew for Hong Kong, or if Kentridge’s great-grandparents had left Vilnius for Berlin instead. It was, at some basic but unarticulated level, what made the idea of showing the two of them in the explicitly post-utopian context of the Chinese capital so appealing. And ultimately so difficult.

“William in Exile: Thoughts on Failed Utopias.” That was the title of the essay that Andrew Solomon wrote for our exhibition catalogue, set to go into production the same week he was seen standing with luminaries and dissidents on the steps of the New York Public Library, in protest of China’s whitewashed presentation at America’s largest publishing confab. A few days later the Chinese publisher canceled our book, owing — they say — not to Solomon but to a text by Kentridge himself, a fugue that leapt from the official ballets in the years of the Cultural Revolution to the ecstatic adolescent ballerinas he saw as a child in South Africa’s East Rand. The day before the opening I couldn’t say no to an invite from Luc Tuymans to sit with him and Ai Weiwei, at a café table across the street from our museum’s entrance, and to wait for the queen of Belgium to make a press visit. Weiwei and I hadn’t spoken in a year, but we were quickly able to reduce a spat that had got very ugly, induced by the sort of quotidian compromise one makes all the time here — the sort Weiwei had just made in order to open a few apolitical gallery shows and pick up his passport — back into the everyday small-p politics of the Chinese art world. The Chinese catalogue having been torpedoed, our Kentridge show opened without incident, and the offending lecture was printed as ten thousand pamphlets of unauthorized samizdat, distributed to every interested ticketholder throughout the summer with no unforeseen consequences.

Two months later, in Geneva for a World Economic Forum thing, I got a call from my office. The Da Hen Li House Cycle, Diao’s expansive recherche on his childhood home in Chengdu, had been censored by the Cultural Bureau, and was endangering the entire 130-work show. These paintings, which he made around the time of the 2008 Olympics, were his attempt to “meet the Chinese audience halfway.” Instead of his usual nested references to abstract expressionism and De Stijl, he reconstructed from his (admittedly fickle) memory the plan of his privileged family’s home, which was seized by the Party after the revolution, turned into the headquarters of the Sichuan Daily, and demolished a few months before his 1979 return trip. Seven years after the paintings were first shown in Beijing, some had become too sensitive to clear customs. The offending canvases included a pair with the single characters for “build” and “demolish,” and another with a timeline positioning events in Diao’s life alongside those of the nation: the founding of the People’s Republic, famines, campaigns, earthquakes. The show opens in a few hours, and for now we have tacked a printed reproduction in place of this key missing work. Hopefully the mention of the Tiananmen massacre toward the right side of the canvas won’t draw the eyes of the inspectors — they usually don’t pay much attention to the English, once things are on site — but I suppose we can never be sure.

In a China where ideological procreation is largely achieved through primary-school curricula and the internet nannies, this sort of analog censorship can seem quaint. The apparatus works not towards the propagation of any specific set of beliefs — those died long ago — but towards its own self-preservation, from the most minor editor or customs clerk thinking about his own career, to the Party thinking about the uncertain future of the state it has built. One can only try to build something that vaguely resembles a public institution in the cracks between these partially enacted regulations, never knowing when or how the rules of engagement might fundamentally change. We know better, albeit only barely, than to long for the clarity of an artistic manifesto, the absoluteness of 20th-century politics, or the permanence of leaving a place for good.