Habeas Corpus

by Matthew J. Abrams

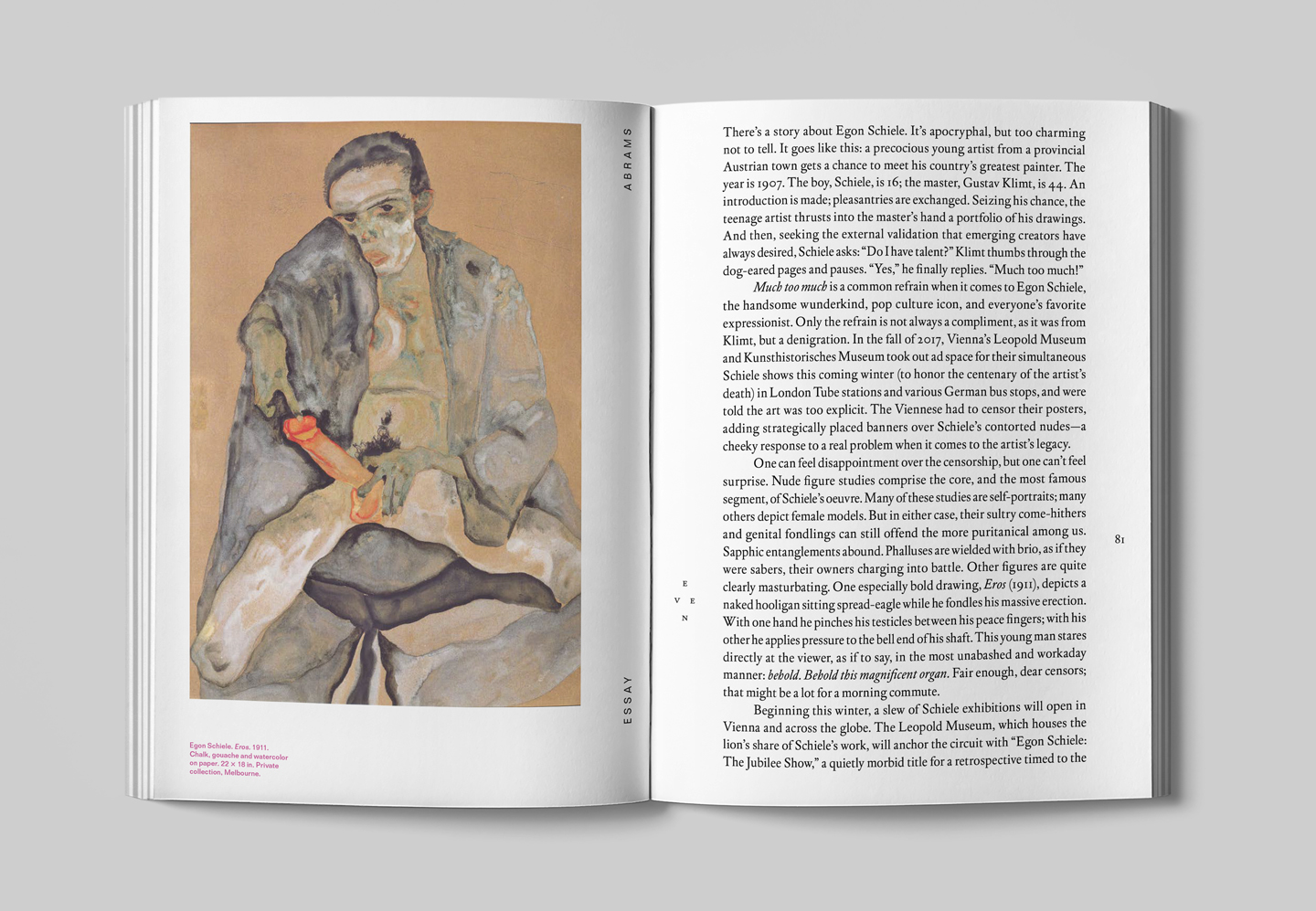

If there’s one thing that connects Schiele’s entire mature output of about 3,000 surviving works, regardless of subject or media, it’s a certain quality of line. There is no line like Schiele’s line. In one sense, it’s a chaotic, stumbling thing, as if made by a hand stricken with tremors, or, as the contemporary artist Wangechi Mutu has smartly described it, a “gorgeous awkward line...like they were drawn by the right hand of a left-handed artist.” Schiele’s line is so contradictory it’s almost indescribable, like a willful unwillingness, or a studied unrestraint. It becomes its most frenetic whenever he depicts a hand, especially his own. The Preacher, a self-portrait from 1913, is typical both of Schiele’s midcareer style and of the unusual postures and hand gestures that he almost always deployed to display himself. We see here the artist’s head droop with one forearm stretched out, as if dancing the robot, while the other contorts into a complex sign, bending his middle and ring fingers over his pinky while splaying his index finger. This was the artist’s most original device, and his exaggerated, increasingly theatrical gesticulations became the markers of a life out of joint.

Similarly, in 1968, Bowie was experimenting with his own pantomime troupe, Feathers, and thinking through what it might mean to communicate through distinct bodily configurations. Eight years later he moved to West Berlin and discovered Schiele. Immediately he seized on the artist’s hands, and by extension the bodily performativity that Schiele’s entire project implied. On the cover of his album Heroes, Bowie assumes a distinctly Schielesque contortion, his left hand extended upwards at an ornery angle, his neck cocked downward as if broken. Bowie then introduced his friend and fellow West Berliner Iggy Pop to Schiele; Bowie photographed the cover of his album The Idiot, where Iggy, too, appears like a broken doll, arms extended with trademark Schiele awkwardness. Thus emerged Schiele’s punk identity, although since that time his influence has oozed from the subculture into the mainstream. Last May, the fashion magazine i-D featured a shoot by Tim Walker that saw models of both sexes crumpling like the Austrian’s models, though they covered their nakedness with Prada, Margiela and Proenza Schouler. If you are not up on your viral celebrity gossip, you may have missed Dakota Johnson revealing a floral tattoo on her right forearm, barely recognizable as a Schiele quotation except for the accompanying hashtag.

Perhaps that’s to be expected: what was pornography in 1910 and punk in 1970 is now, quite simply, contemporary. Despite the anxieties of the London Underground’s ad sales team, Schiele’s transgressions can no longer be counted on to shock the bourgeoisie. The stakes of Schiele today, or his value to younger generations who may have never heard of him or Major Tom, is therefore not his erotics but his politics — his pure, complete autonomy and non-commercial originality.