February 2017

Twirl your leg around, twirl it right back; bend at the hip, come back upright. Lunge forward, bend down, lunge forward, stand stock-still. And pay no attention to the music behind you: a plunking piano score, played live, that seems to have as little discernible grammar as the dance you’re performing.

Merce Cunningham and Meg Harper in Rainforest, with costumes by Jasper Johns and decor by Andy Warhol. 1968.

Merce Cunningham: Common Time

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Opens February 8

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

Opens February 11

Twirl your leg around, twirl it right back; bend at the hip, come back upright. Lunge forward, bend down, lunge forward, stand stock-still. And pay no attention to the music behind you: a plunking piano score, played live, that seems to have as little discernible grammar as the dance you’re performing. Suite for Five (1956), with a score by John Cage and peppy bright-colored costumes by Robert Rauschenberg, offers an early taste of the choreography of Merce Cunningham (1919–2009), the scion of Black Mountain College who shook up every assumption in dance. Quotidian movements, like walking or sitting, now had the same prestige as a fouetté turn; action on the side or back of the stage had as much significance as action at the center. Perhaps his most important innovation, which he and Cage came to together, was to divorce dance from music, and insist that dancers ignore the beat of the accompaniment and perform at liberty. (The troupe learned each work’s choreography in silence.)

Cunningham’s lack of self-obsession endeared him to a stunning range of collaborators: Johns and Rauschenberg, Stella and Warhol, Nam June Paik and Rei Kawakubo. Cage, however, was his truest partner, in art as in life, and it was he who drove Cunningham to introduce chance into the composition of his dances. Rather than plot a dance through trial and error, Cunningham flipped pennies, or the divining rods of the I Ching, to sequence movements and even to determine how many dancers would appear. (The composer Morton Feldman, on Cunningham’s habits: “Suppose your daughter is getting married and her wedding dress won’t be ready until the morning of the wedding, but it’s by Dior.”) If this sounds like mere play, it is anything but. Cunningham, who trained under and greatly admired Martha Graham, continued the elder choreographer’s escape from classical ballet, but where she preserved emotion and expression, Cunningham favored mechanics and movement for its own sake, and chance was one way to get there. What is a painting? Just pigment on a flat surface. What is a dance? People moving.

You’ll have to brave the nasty winter in two different Midwestern cities to get the full view. The Walker, which owns the set and costume archive of Cunningham’s company, will present six decades’ worth of his physical relics, as well as later artworks by admirers such as Tacita Dean. In Chicago, the focus is on Cunningham’s multimedia work, and that show will feature a recreation of one of his signal experiments of the 60s: Rainforest, set to a score by the electronic composer David Tudor and decked out with shiny Mylar balloons inflated by Andy Warhol. Once it was nonsense to present dance in a museum; now no institution is complete without writhing performers in an oversized atrium, and the last few years have seen Yvonne Rainer, Sasha Waltz, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, and a host of younger choreographers migrate from the proscenium stage to the white cube. It all started with Merce, whose dances obeyed every rule and yet knew no limits.

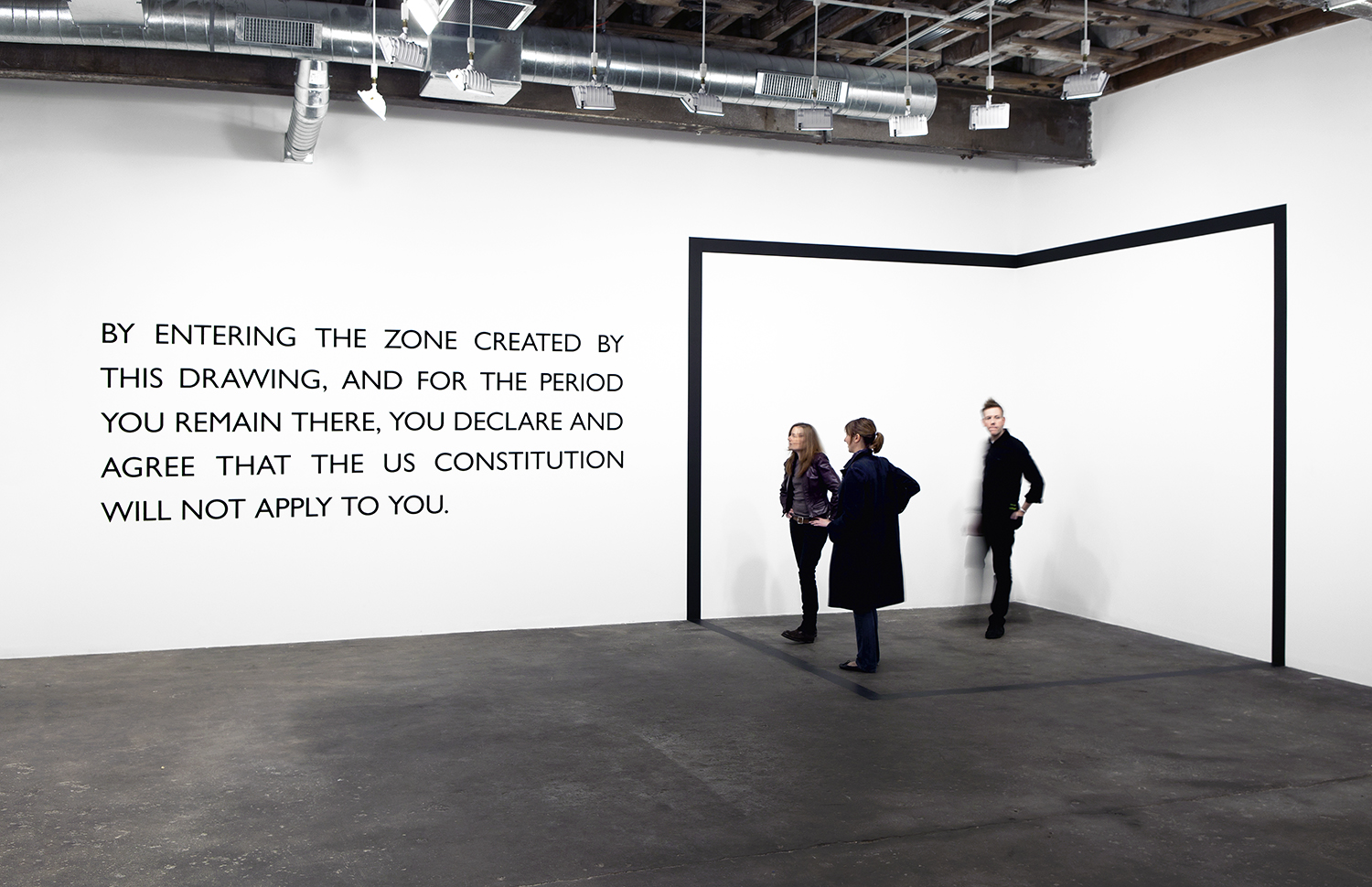

Carey Young

Dallas Museum of Art

Opens February 2

Born in Zambia, based in London, Young at last gets her first stateside solo — which will include some of her most frank meditations on power and its abuses. Of note is her timely new film imagining a girls-run-the-world form of justice: it portrays female magistrates at the bombastic Palais de Justice in Brussels, the largest courthouse ever built.

N.S. Harsha

Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

Opens February 4

The Indian painter is as apt to depict laborers at sewing machines as dragons in midair, and yet even the most realist of his works seems to follow the logic of dreams. A full-dress midcareer retrospective, this show should go some way to revealing the sources behind Harsha’s art, equally indebted to mass-media manga and Mughal miniatures.

Svenja Deininger

Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach

Opens February 4

The Austrian painter’s cunning, meandering abstractions are easy to love but hard to decipher, and often make use of soft color (even a little gold) and almost-but-not-quite symmetry. More than two dozen works, all from the last five years, reveal a painter who makes no distinction between expression and restraint.

Raymond Pettibon

New Museum, New York

Opens February 8

The artist has kept his punk spirit and angst well past middle age, and hopes this retrospective will make viewers feel as if they’ve been “shouted at or spoken to in a multitude of voices.” Over 700 caustic, comic drawings are on view, including childhood work and zines (which predate even that album cover that inspired a thousand regrettable tattoos). Travels to Maastricht in June.

Art et Liberté

Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid

Opens February 14

Five years in the making, this very important exhibition of the Cairo-based collective Art et Liberté advocates for a rethinking of the Surrealist movement. Local in action and international in view, the politically engaged group used art as a toolkit for resistance and reform during the years of Egypt’s colonial rule and at the cusp of the second world war. Organized by the independent curatorial group Art Reoriented, the show was seen earlier at the Pompidou and travels to Dusseldorf and Liverpool next.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Tate Modern, London

Opens February 15

After a 2003 show at Tate Britain, now comes a major retrospective at the museum that has feted him the most. But how could a post-Brexit show from Tillmans, who so passionately supported the Remain campaign — and created its iconic posters — not have rattling political undertones? The most dramatic turn in his work (which also marks the chronological beginning of the exhibition) occurred after the invasion of Iraq, and this show, as Tillmans tells is, has no lesser duty than “to defend the pillars of the free world order.”

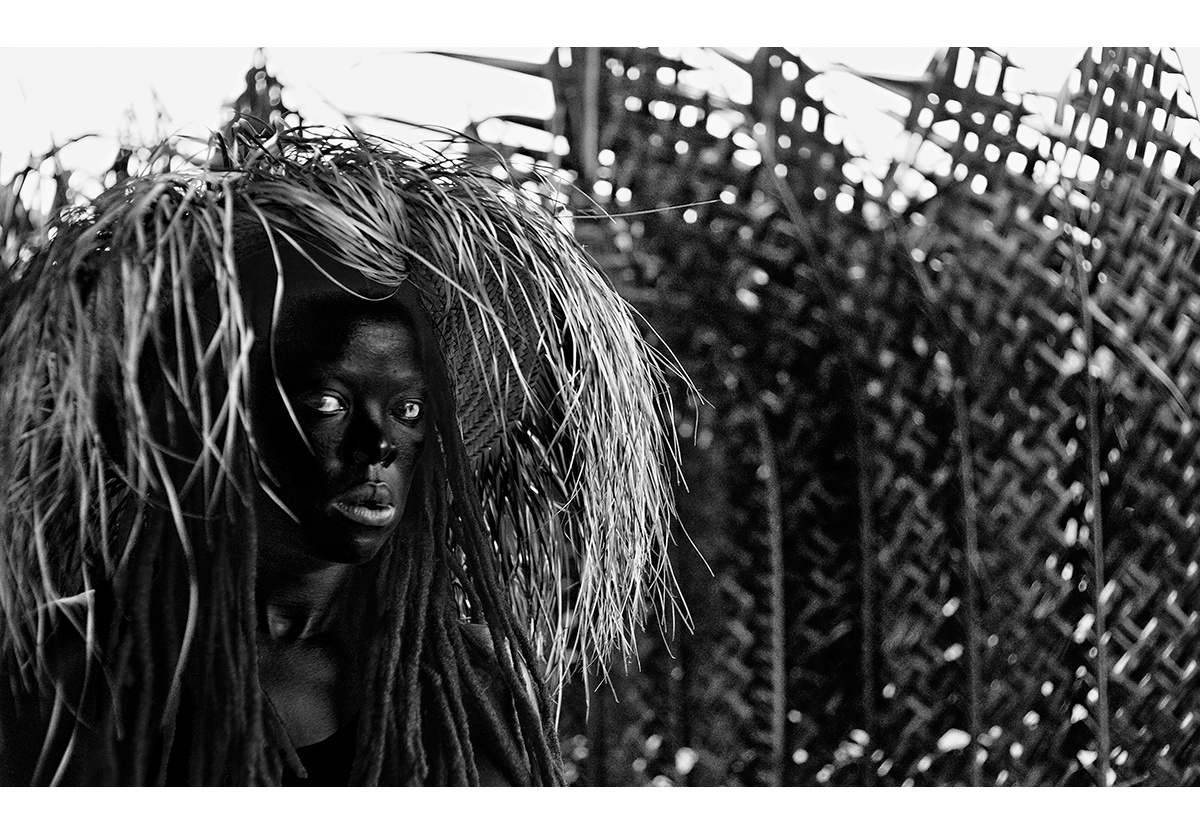

Zanele Muholi

Maitland Institute, Cape Town

Opens February 15

The inaugural show at this new arts institution goes to the South African photographer and activist who won international renown — but also faced violent reprisals — for “Faces and Phases,” her years-long project documenting the lives and loves of black lesbians. Lately, though, Muholi has turned to making self-portraits ironically accessorized with bottle tops, plastic bags, or cheap wigs, and her enduring glamour is both a personal provocation and a political action.

Eduardo Paolozzi

Whitechapel Gallery, London

Opens February 16

Pop Art: an American enterprise born in Britain. This weighty, long-time-coming retrospective reintroduces the Scottish-born printmaker who was making collages of pinups, Lucille Ball, and Dr. Pepper as early as 1947. Also included are his less-known textile designs, as well as maquettes for the rather tasteless sculptures that dot some of Britain’s public spaces.