May 2018

Jutta Koether. Roots in the Rhineland. 1995. View in "Jutta Koether/Philadelphia," organized by Bortolami.

Jutta Koether: Tour de Madame

Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Open May 18

In German, married or older women take the nothing-special honorific Frau; in French, madame has a rather more complex ring. It just means “my lady,” but since its emergence over 400 years ago, this innocuous portmanteau has picked up a battery of connotations, sometimes glamorous and powerful, sometimes insalubrious. When you call someone “Madame” you’d better know the context. A madame can be stately (think of Madame Chiang, as the widow of Taiwan’s first leader was known), can be provincial (think of Emma Bovary, who keeps her title in English), or can be in it for herself: across a spectrum of urban dictionaries, a madame is the proprietor of a brothel. One of the most powerful women in any society, to be sure. But perhaps ever so slightly less polite.

Regardless, it’s safe to say that in 2018, a German artist does not come back to her home country for the most significant retrospective of her career and idly choose “Tour de Madame” as a subtitle. Jutta Koether, a powerhouse of painting who left Cologne for New York in 1991, has done precisely that, and it’s all a little more jarring given the collection of the Brandhorst Museum, privately amassed by heirs to the Henkel fortune and donated to Munich in 2009. After nearly a decade, it’s still dominated by Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly, Mike Kelley, Damien Hirst, and an unrelenting barrage of other men. Koether, whose recent work playfully bathes and prances in a complex network of citations and revisions, has always taken a male-dominated history of art as her rightful inheritance. Now at last comes the “turn of Madame”: of the lady, of the whore, of the heiress.

Koether’s work is intentionally difficult, in part because she is cleverly diverting the history of painting away from understood tropes of color, content, and composition. Where an earlier generation in Cologne tried to break out of painting’s dead ends by making paintings as ugly as possible, she prefers programmatic reds and blacks, repetitive checkerboards and sickly-sweet heart-shaped canvases. And she has relentlessly adapted the works of her male predecessors, turning to Chardin, Cézanne, Balthus, and, most successfully, Nicolas Poussin’s Biblical epic The Four Seasons. She’s even repainted Queen Elizabeth, her wavering brushstrokes mirroring the uncomfortable meeting between the sovereign and Angelina Jolie — two dames in their own right. Discomfort is intentional, and only made more apparent in person; Koether considers methods of display to be a crucial performative aspect of her work. The paintings don’t ever appear on their own; you might find her propping canvases against columns, hanging paintings across thresholds, and attaching others to freestanding glass panels, in the manner of the Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi.

This outing boasts over 150 works, including a brand new 12-part series inspired by Cy Twombly’s Lepanto Cycle, owned by the Brandhorst and on permanent display at the museum. Expect real gamesmanship; Koether can play with the best of them, and never misses an opportunity.

Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art

Tate Modern, London

Opens May 2

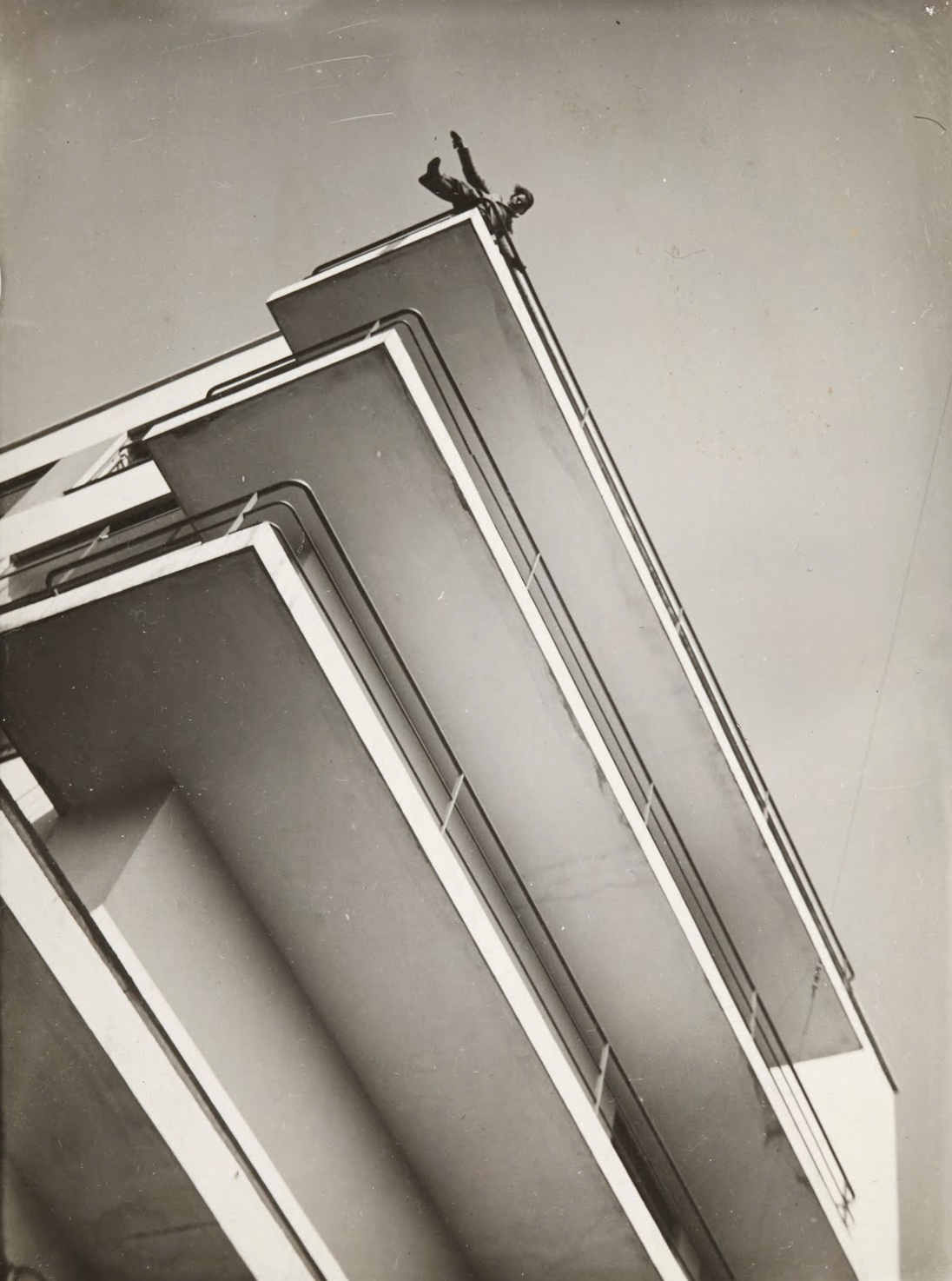

About 80 years passed between the invention of the camera and the coming of painterly abstraction, but this show argues you can’t have one without the other. It will place pioneers of abstract painting, from Braque and Pollock to Bridget Riley, alongside photographers such as László Moholy-Nagy and Barbara Kasten, whose own images draw on techniques of painterly nonrepresentation.

Renoir: Father and Son

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Opens May 6

The Rules of the Game, Grand Illusion, Boudu Saved from Drowning, The Lower Depths: the films of Jean Renoir transformed early sound cinema with their flawless storytelling and unflashy humanism. How much came from his father Pierre-Auguste, known for splashy bourgeois party scenes and, later, soft-bottomed nudes? This exhibition of cinema and painting, at a museum home to more than 180 works by Renoir père, offers an answer.

Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Opens May 10

Santo cielo, this could go either way. The Met’s possibly blasphemous show puts papal robes and priestly vestments, many on loan from the Vatican, alongside ecclesiastically inspired gowns by Valentino, Versace, and Dolce & Gabbana. The cardinal of New York should be at the Met Gala, though we are more excited to see what chasuble Rihanna will wear.

Franz Erhard Walther

Estancia FEMSA—Casa Luis Barragán, Mexico City

Opens May 12

The veteran German artist won the Golden Lion at the last Venice Biennale, and for good reason: after half a century, his dual obsessions with textiles and performance have lately become the hottest thing going. This exhibition, fittingly taking place at one of the most color-saturated houses in the western hemisphere, unites Walther’s early fabric works, meant to be touched and sometimes worn, with a new, site-specific drawing that riffs on the luscious minimalism of Barragán’s home.

Masatoshi Naito

Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Opens May 12

A long-time-coming survey of one of the undersung masters of the photography scene in 1960s Tokyo, whose gritty black-and-white imagery has defined the country’s artistic image ever since. Like many of his colleagues, Naito captures night-owl low-life Tokyo with slurred, grainy compositions — but he has also spent decades picturing rural Japan and its folkloric traditions. This show brings his full achievement forth for the first time.

Garden of Memory: Etel Adnan, Simone Fattal and Robert Wilson

Musée Yves Saint Laurent, Marrakech

Opens May 14

"Marrakech taught me color," said the French fashion designer, whose commemorative museum opened last year in a low-slung beauty of a brick building by the architectural firm Studio KO. Though YSL’s gowns are the focus here, they are also presenting temporary exhibitions — and this one, examining three intertwined talents of painting, sculpture and theater through the lens of Morocco, is a promising first outing.

Echo and Narcissus

Palazzo Barberini, Rome

Opens May 18

One of the Italian capital's most beautiful museums is expanding into 11 previously empty new rooms of its 17th-century palazzo, and inaugurating them with a showcase of portraiture drawn from its own collection and that of its frenemy, the contemporary art museum MAXXI. Expect Caravaggio alongside Kiki Smith, Raphael facing Richard Serra, Bronzino staring down the Arte Povera gadfly Giulio Paolini: a very Italian marriage of old and new.

16th Venice Architecture Biennale

Giardini della Biennale and Arsenale, Venice

Opens May 26

Once the forgotten stepsister of the Giardini, the architecture biennial got more ambitious in its last two editions, curated by Holland’s Rem Koolhaas and Chile’s Alejandro Aravena. This year’s organizers — Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, who lead the quietly influential Dublin firm Grafton Architects — want to continue an escape from spectacle; as these Irishwomen like to say, “We see the earth as client.”