Love and Theft

by James McAuley

Six years ago the German tax police entered a modest apartment and found more than a thousand works of art. What crimes, and whose stories, lie beneath the Gurlitt Collection? A report from Bonn and Bern.

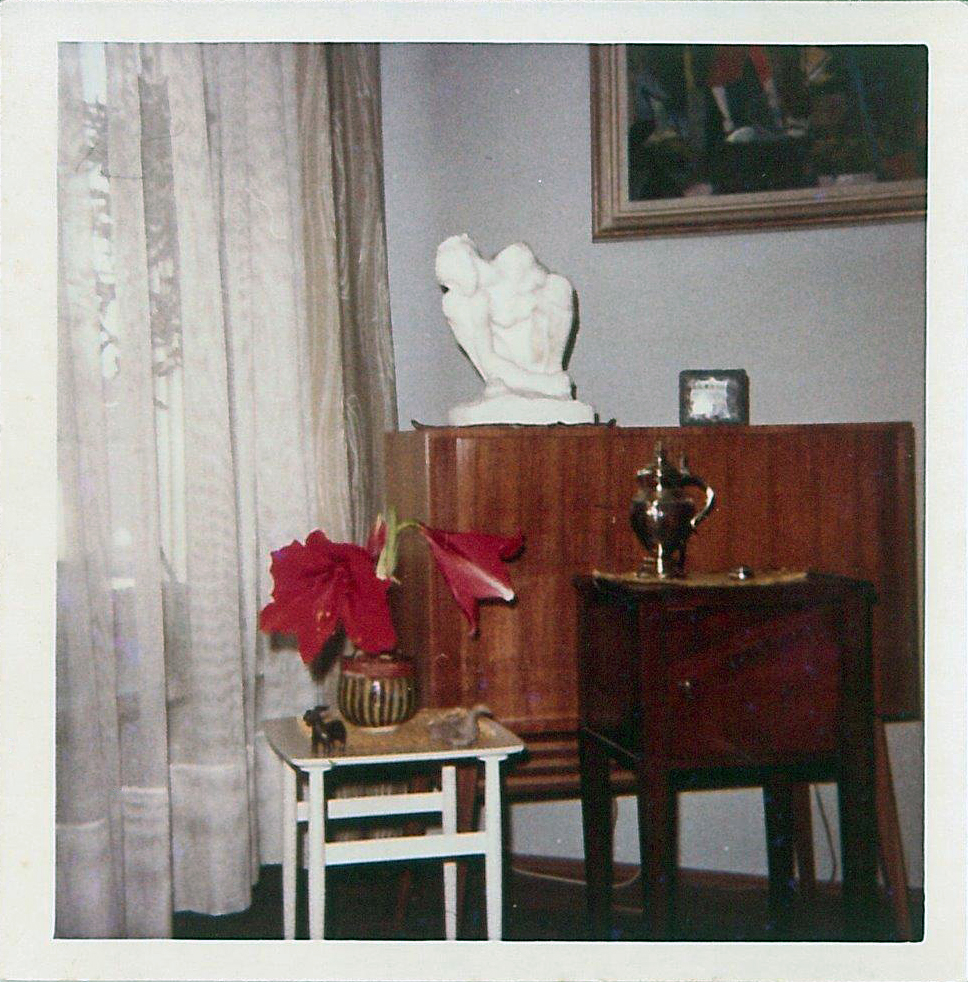

The press gets a first look at a marble by Auguste Rodin, formerly in the collection of Cornelius Gurlitt and bequeathed to the Kunstmuseum Bern. Photo: David Ertl.

Really, the only thing that spoke to me was the Couture.

I.

Portrait of a Young Woman, completed between 1850 and 1855, depicts a nameless brunette seated in profile, her left hand grazing her bust. The expression on her porcelain face is something of a smirk — not a mysterious smirk, but an amused smirk, slightly inviting but mostly condescending. Thomas Couture, a mid-century academic painter now mostly remembered as the teacher of Édouard Manet, depicts the kind of 19th-century bourgeois Parisienne who would have aroused the ambitions and the anxieties of Balzac’s Rastignac, with her glassy eyes that rarely see things clearly except when confronted with those who don’t quite belong. The woman fingers the small crucifix she is wearing, which has fallen to her breasts. What she has you want but cannot have. She knows that, but you don’t. Not just yet. As it turns out, there is quite a lot we do not yet know about Portrait of a Young Woman, which is hanging for the moment at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, Germany — and whose provenance, a panel alongside it declares, is “undergoing clarification.”

Kunstmuseum Bern, bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt. Provenance undergoing clarification.

I had come to Bonn for the victims. In the former provisional capital of West Germany, the exhibition “Gurlitt: Status Report” is supposed to be about them, the people who suffered at the hands of Hildebrand Gurlitt, one of Nazi Germany’s state art dealers, a man who amassed an enormous collection through highly dubious means. It is one of two concurrent shows presenting the Gurlitt collection to the public for the first time; the other is at the Kunstmuseum Bern, in Switzerland, to which Hildebrand’s son Cornelius left his hoard upon his death in 2014. Some of the pieces in the Gurlitts’ charge had previously been looted from prominent Jewish collectors and dealers; others were purchased legally, but often from Jewish clients who had no choice but to sell. This is what the exhibition tells us we should pay most attention to: not the paintings, but the provenance. As an explanatory text reads near the beginning of the exhibition: “The seemingly prosaic list of particulars that accompanies each of the works shown in this exhibition — and that ideally provides an unbroken record of ownership from the artist’s studio to today — conveys not only information about the history of the object but also about the people who owned it.”

But what is it that we learn about the owner of this striking Couture? “Very likely until 1940,” we read, it hung in the Paris apartment of Georges Mandel. That is all. As someone who lives in France, I happened to know the story of Mandel, and must admit to having been taken aback, in a show nominally about victims, that this was all there was of him, a name written on a wall.

Nowhere to be found anywhere in “Status Report” was the fact that Mandel was among the most prominent French — and Jewish — politicians of the doomed cabaret that was the Third Republic. Although an optional audio guide explanation tells some of his story — mostly the fact that he was born a Rothschild — we neither see nor feel that he was France’s interior minister at the time of the Nazi invasion, and soon met a devastating fate. Mandel was among the 80 members of parliament who opposed the establishment of the Vichy government, and who fled to Algiers in the summer of 1940. In North Africa, he became a leader of the “Free French,” but Vichy authorities captured him in 1941, and sentenced him to life imprisonment. When the Germans took over the unoccupied zone the following year, Mandel was eventually deported to Buchenwald, where he was interned alongside the former prime minister Léon Blum and other French elites who had resisted Vichy. He was eventually returned to France as a prisoner of war, but was captured by the infamous paramilitary “Milice” in 1944. They shot him dead in the forest of Fontainebleau, like an animal.

“You fear for me because I am a Jew,” Mandel told a British officer in the summer of 1940, after being offered safe passage to London, along with Charles de Gaulle. “Well, it is just because I am a Jew that I will not go with you tomorrow; it would be interpreted as an act of cowardice, as if I were running away.” It was a remark that typified Mandel’s patriotism and pride, but not a word from him appears in “Status Report.” Nor do audiences learn — in a show nominally devoted to the initial owners of this stolen art — that Mandel’s lifelong partner, the French actress Béatrice Bretty, reported the loss of the Couture after the war, never to see it again.

Both in Bonn and Bern, the two shows titled “Status Report” had all the typical discomforts of a major museum blockbuster: too many visitors crowded into the same overheated spaces, vying for glimpses of art they may or may not understand. The iPhones were out; the Instagrams were posted. These particular shows, after all, bill themselves as a “moment,” the kind that demands the urgency of instantaneous recording and, it would seem, the most somber of hashtags. For once, I was glad I had my phone as well. As I ambled through the Bundeskunsthalle, I realized that the smartphone was the only indispensable guide to the narrative presented on the walls, as only it could show me the faces of victims like Mandel, who were nowhere to be seen, absent even in a space consecrated in their honor. What we saw instead was the specter of Hildebrand Gurlitt, the dealer who swindled them all. If this may have its purposes, none of them has anything to do with the memory of Georges Mandel or any number of lesser-known Jewish victims. And this, of course, was always going to be the problem.

II.

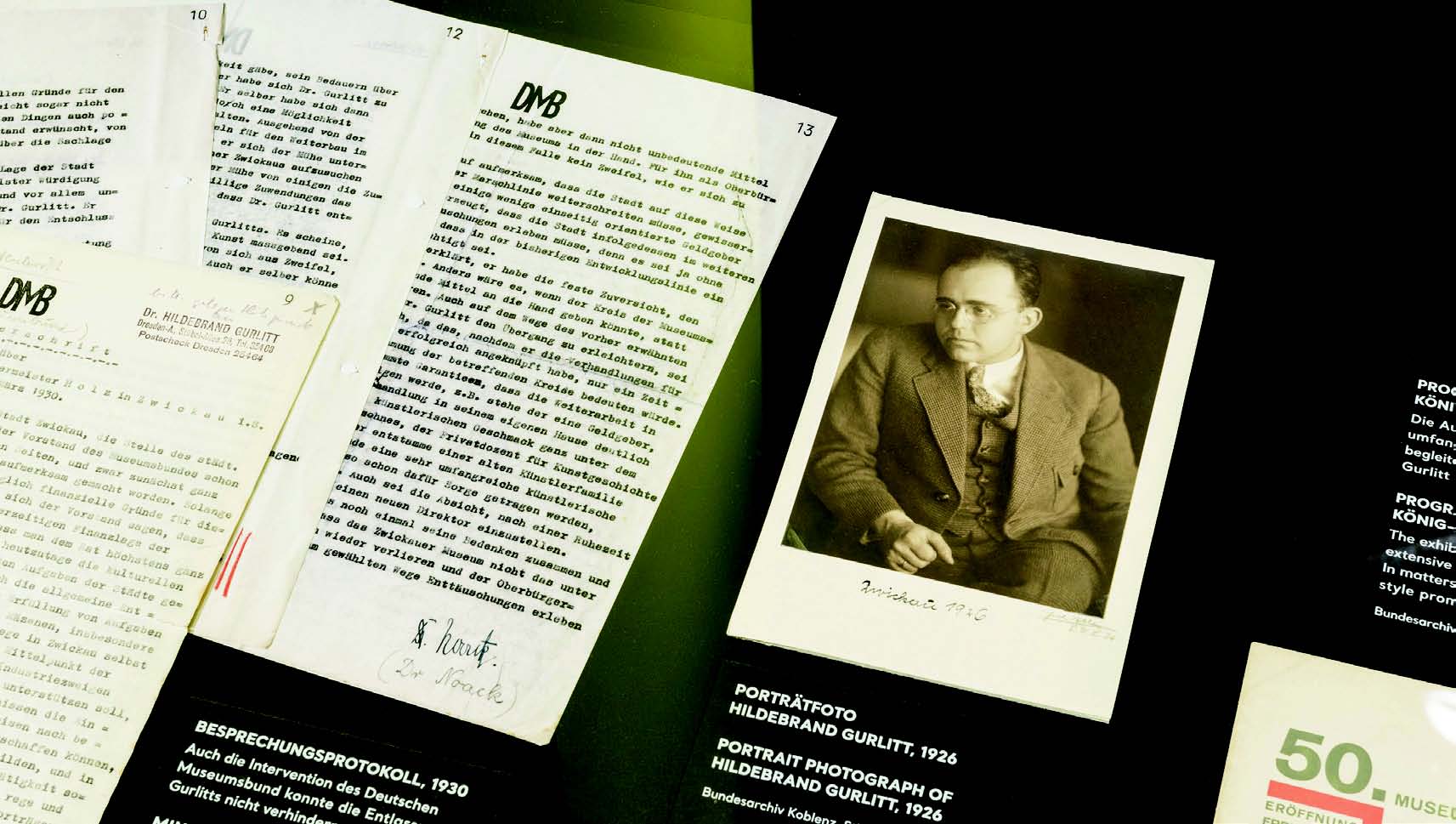

In the fall of 2013, when the news broke that German investigators had seized more than 1,300 artworks from an apartment in Munich’s tony Schwabing district the year before, it seemed as though we had the next Holocaust blockbuster on our hands. During the Nazi era, the dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895–1956) had used his considerable charm to secure a position as one of the dealers for Hitler’s pet project: the Führermuseum, a massive art temple planned for his hometown of Linz, intended to project an image of the regime’s aesthetic power. Gurlitt was a trained art historian, museum curator, and gallery owner, and also a member of the Commission for the Exploitation of Degenerate Art, which permitted a small network of dealers to sell — and profit from — works of so-called “degenerate art” confiscated from private collections and German public museums. But here was the catch: Hildebrand Gurlitt was not your basic Nazi. He was also partially Jewish — a quarter, to be exact, and paternally, so not by halacha. It did not matter. Mouths watered; a “complicated character” was born. Stir in the circumstances of the collection’s discovery — in the lonely apartment of Gurlitt’s reclusive 80-year-old son, Cornelius — and this was no longer a rehash of the Rape of Europa narrative. This was media gold, in the sense of The Woman in Gold: art and death, kitsch and catastrophe.

The international press wasted no time in casting the story in these Spielbergian dimensions. In what soon became the iconic image of the entire affair, Der Spiegel put Cornelius Gurlitt on the cover of its issue of November 18, 2013. The old man was pictured in what looks like the dining car of a train, a nervous grin on his face (he died the following year). “Interview with a Phantom,” the headline read. For Le Monde, the 1,300 works uncovered in his apartment, plus another 186 works found in Cornelius Gurlitt’s second home in Austria and even a Monet found in a suitcase, were “an incredible discovery.” For the New York Times, the Gurlitt trove was “one of the biggest finds of vanished art in years,” but one that “left almost equally big questions unanswered.” The screenplay writes itself.

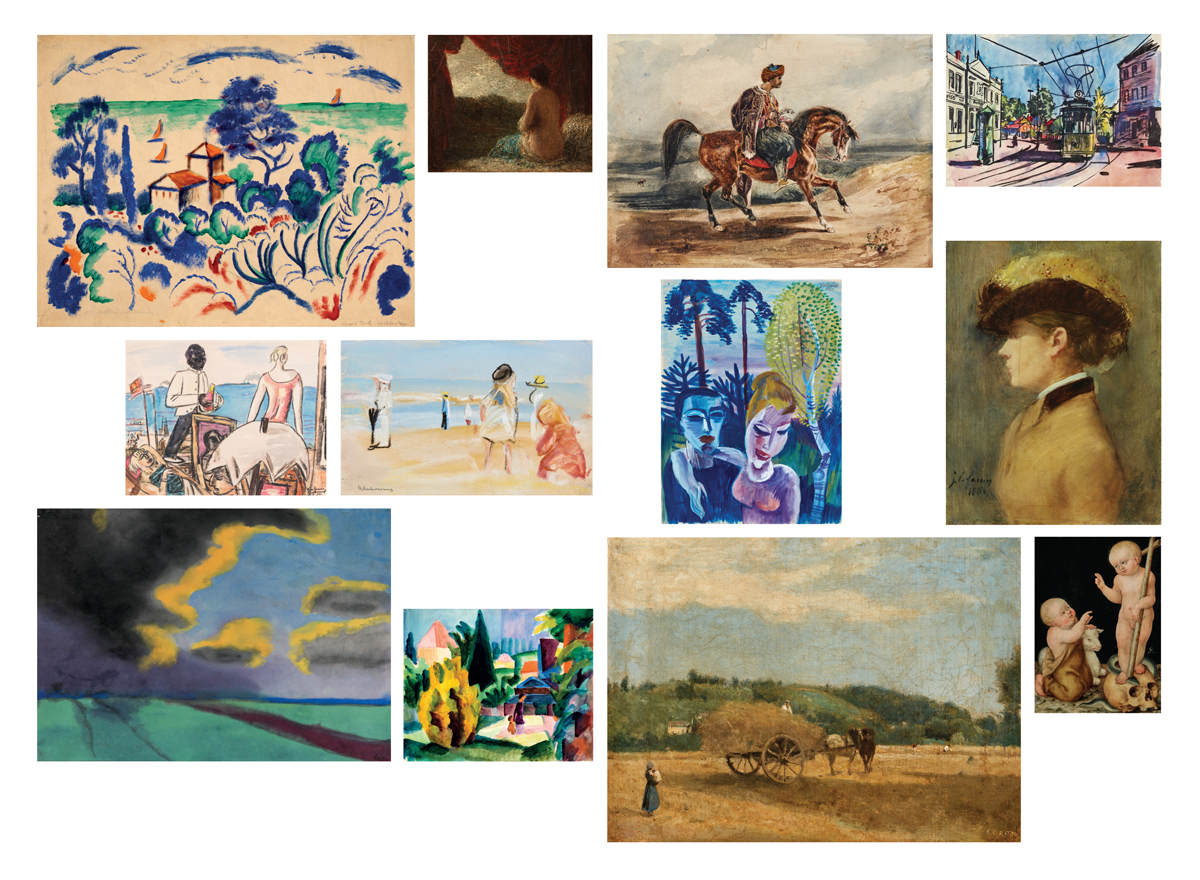

But then the facts began to trickle in. What had initially been billed as an astronomically valued collection of canvases by Chagall, Picasso, and Matisse began to appear as a collection whose guiding principle was quantity instead of quality. Doubts reemerged as to the nature of Hildebrand’s allegedly discerning taste. “Dr. Gurlitt was not very particular about the quality of the artworks and above all demonstrated a desire to acquire works of art for marks.” Such was the assessment Michel Martin, a former Louvre curator, gave in testimony to the Allied forces after the war — and, given the amount of genuinely fine art that Nazi dealers had at their disposal, it was meant as a withering critique. It still stands. The art in Bonn and Bern adds up to a collection of no particular distinction, larded with trite, second-tier works on paper by artists of middling distinction, and the real, unexpected achievement of “Status Report” is that it exposes the truth about Hildebrand Gurlitt — his mediocrity, his uncomplicated interiority, his utter predictability. (As it turns out, one of the centerpieces of Gurlitt’s treasure trove, a somewhat predictable nighttime dreamscape billed in the press as a lost Chagall “masterpiece,” is not here. It was a fake, said the committee tasked with authenticating Chagall’s work.)

For too long, the juxtaposition of the words “Nazi” and “art” has created a kind of mystique, an obsession that communicates an indescribable rupture in a language of beautiful things. There is an elitism that often characterizes this dark commodity fetishism, one that can privilege the stories of the finest objects and, by extension, the wealthiest victims, those who had the means to procure such fine pieces. Edmund de Waal’s lyrical memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010), is ultimately the story of the Ephrussi family, one of the richest Jewish banking families in modern European history, and their collection of Japanese netsuke that travels through time and place. Likewise, the plot of George Clooney’s The Monuments Men (2014) hinges on the stories of “great works” by Michelangelo, Van Eyck, and others that came from “great collections”: those of the Rothschilds, the Catholic Church, and the list goes on. By contrast, “Status Report” takes us closer to the reality of Nazi plunder, which was at least as mundane as it was monumental, and often involved unremarkable items that are worth remembering only because they were once stolen. What we learn in the end is that Gurlitt was not that interesting, and this is an urgent message. Sometimes in real life the characters are flat. Sometimes there is nothing to be found.

Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn. 2017–2018. Photo: Oliver Berg/DPA.

III.

Hildebrand Gurlitt came from a provincial bourgeois family in which an appreciation for the arts was almost mandatory. The Gurlitts hailed from comfortable, conservative Dresden, not from Berlin or Vienna, and the respective revolutions of taste that began in either place took quite a bit of time to reach them. Hildebrand’s paternal grandfather Louis Gurlitt (1812-1897), for instance, was a painter of prosaic landscapes that were not so much romantic as prematurely sentimental, nostalgic for a world that had not yet vanished. In the same vein, his father, Cornelius Gurlitt (1850-1938), was an art historian, but one whose primary interest was in the conservation of Saxony’s innumerable examples of fine Baroque architecture. Nearly all of this preservation was ultimately in vain, as Allied bombers would raze Dresden by 1945, seven years after his death. To this day, perhaps the most iconic image of postwar Germany remains the view from the Dresden Rathaus, taken by the photographer Walter Hahn, that shows a statue known as the Allegory of Goodness gazing out over untold destruction. One thing that was not destroyed, however, was the legacy of the Gurlitt family, which survives — then as now — in a Dresden street named after Hildebrand’s father: Cornelius-Gurlitt-Straße, a short extension of the leafy avenue where the family’s villa once stood. In any case, Hildebrand fit well into this bourgeois cosmology: like his father, his grandfather, and two uncles before him, he made his career in the arts, but without any real distinction.

After taking his doctorate in Frankfurt, Hildebrand took up a post in 1925 as the director of what was then the King Albert Museum in Zwickau, a smaller city in his native Saxony. This was a job that, at the age of 29, he seemed to view as a stepping stone, though to where, exactly, is not quite clear. As he later wrote — not without a certain degree of self-estimation — his role was to “eradicate some of the general awfulness” of drab, industrial Zwickau by creating a museum that would serve as a cultural consulate for the avant-garde. In this way, Hildebrand differed from his family: the first exhibition he staged was a retrospective of the German expressionist painter (and Zwickau native) Max Pechstein, a member of Die Brücke, the radical school his father had disliked. Along similar lines, he quickly used the museum’s budget to acquire pieces by Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Marc, Oskar Kokoschka, Emil Nolde, and other painters whose art would be labeled entartete (“degenerate”) in the following decade. By all accounts, Hildebrand had a flair for scandal: among his most popular shows was a 1928 exhibition of art that depicted sexually transmitted disease, which drew 7,500 visitors, a record for the King Albert Museum. As it happens, that museum now bears the name of Max Pechstein.

This element of Hildebrand’s taste is the subject of the other half of “Gurlitt: Status Report,” at the Kunstmuseum Bern. The show in the Swiss capital tries to illustrate the workings of Nazi art policy through Gurlitt’s cache of pictures, and indeed, as several better recent exhibitions have shown, the Nazi assault on modern art was far more than a peripheral matter of aesthetics. The realms of visual and material culture were central to the regime’s project of “purification”; they were its principal vectors of self-expression, an obsessive language of public power. Even in 1945, when he was driven into the bunker where he would commit suicide, Hitler still pored over the plans for his beloved Führermuseum, which was to be his great rejoinder. In any case, Entartete Kunst was Hitler’s rejection of the world that had rejected him: the Vienna of Stefan Zweig, the Berlin of Christopher Isherwood, and, in general, the social and political upheaval that rocked Europe’s great capitals in the wake of the First World War. Perhaps nowhere was that upheaval more tangible than in Weimar Germany, a fleeting Xanadu of artistic experimentation, sexual liberation, and cultural cataclysm. Those who made names for themselves in this brave new world were themselves evidence of its revolution. “Weimar culture was the creation of outsiders, propelled by history into the inside, for a short, dizzying, fragile moment,” wrote the great historian Peter Gay. Jews, gays, communists: Weimar was refuge for them all.

Almost immediately after coming to power, Hitler sought to consolidate his position by liquidating the art that these “outsiders” had created. Modernist art was purged from German museums and, later, from private German collections before being sold abroad to profit the regime. Some 650 of these confiscated pieces were exhibited in the infamous Degenerate Art show in Munich in 1937, where more than two million people saw works by Picasso, Chagall, Kandinsky, and others on walls emblazoned with angry accusations such as “Revelation of the Jewish racial soul,” or “The Negro becomes the racial ideal of a degenerate art.” Crucially, the concept of “degeneracy” was never defined in aesthetic terms, and thus could be used as a weapon when required. Indeed, just a small number of “degenerate” artists were Jewish; some, such as the painter and printmaker Emil Nolde, were themselves avowed Nazis.

Hildebrand Gurlitt was among the dealers permitted to sell these “degenerate” works outside of Germany. Unlike Hitler, he actually liked them. Yet the show in Bern tells us little about the Nazis’ art policies, nor about Gurlitt’s symbiotic relationship with the regime. In fact, all we see of him here are the vague contours of his life as a collector — and, indeed, not a particularly discerning one. There are, of course, some delights on view: Max Liebermann’s halcyon pastel of Wannsee comes to mind, as does Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Two Nudes on a Bed (c. 1907–08), a chalk drawing of two women whose figures are outlined in bold strokes of primary colors. In a drawing whose dimensions are small, the effect is a powerful one: with simple strokes of a crayon, Kirchner projects an aura of evolving emotion, a spectrum of subjectivity that sheds an intimate light on the inner lives of two otherwise anonymous, undefined figures. This particular Kirchner also encapsulates the strangeness of the Gurlitt story quite well. In 1928, Hildebrand acquired it for Zwickau; in the mid-1930s it was confiscated from the museum; and in 1940 Gurlitt used his new position to purchase the pastel for himself, after which it never left his collection.

Kunstmuseum Bern, bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt.

But in Bern these rare accomplished works hang amid assorted pieces — primarily drawings and lithographs — signed by various “degenerate” artists that are not even particularly illustrative of their alleged “degeneracy.” There is also no serious attempt to recreate visually how, exactly, Entartete Kunst was defined and displayed at the time. This was a particular achievement of another recent show on the subject, “Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937,” at the Neue Galerie in New York in 2014. Through reproductions of posters, photographs of gallery displays, and museum catalogues — not to mention the individual biographies of the personalities involved — the Neue Galerie show successfully captured the contradictions at the heart of the Nazi aesthetic campaign. In Bern, by contrast, the show feels like a collection of disparate souvenirs. In the end, do the etchings of landscapes that Max Liebermann drew late in life — scenes like Strandszene and Im Tiergarten, both done in the early 1930s — tell us much about “degenerate art”? Liebermann (1847–1935), a Jew, was obviously despised by the Nazis, but “Jewishness,” however imagined or defined, is hardly all there is to say about Nazi views of “degeneracy.” In that way, the Bern show suffers from a strange hesitation to engage with the shifting boundaries of a fabrication that never was — and that should not be considered — an idée fixe. At the same time, while we never forget that we are looking at pieces from Gurlitt’s collection, we lose sight of the man who amassed these objects. Where did he fit on this spectrum?

A crucial question is whether the young Herr Doktor Gurlitt — as ambitious and aspirational as he was — genuinely appreciated and understood this contemporary art for its intrinsic aesthetic value, or whether he merely saw in it an express ticket to critical acclaim and feuilleton fame. When the news of the Gurlitt art hoard broke in 2013, the public was immediately captivated by many elements of the story, with its peculiar blend of the absurd and the grotesque. But chief among these public fascinations — fueled no doubt by the remarkable interview that Hildebrand’s son, Cornelius, gave to Der Spiegel shortly thereafter — was the notion of the Gurlitts as a family of archetypal aesthetes, withdrawn from the chaos of an illegible world into a cultivated chrysalis of “art for art’s sake.” As Cornelius told the magazine, “there is nothing I have loved more in my life than my pictures.” The reporter then asked the old man whether he had ever loved a human being in the same way. Cornelius giggled, dismissing the question. “Oh, no,” he said. Cornelius appears in this exchange almost as a latter-day Jean des Ésseintes, the decadent antihero of Huysmans’s 1884 novel À Rebours: “He wanted, in short, a work of art both for what it was in itself and for what it allowed him to bestow on it; he wanted to go along with it...into a sphere where sublimated sensations would arouse within him an unexpected commotion.”

But there is little evidence that what may have been true for the son was likewise true for the father. Ever since his days as an army press officer on the eastern front in World War I, Hildebrand showed a remarkable facility to befriend everyone worth knowing, and just at the right time: the painter Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, the writer Arnold Zweig, the department store magnate Salman Schocken — who financed many of his purchases in Zwickau — and, later, Nazi elites who would spare him from military service. While still in Zwickau, he seemed at least as proud of the press his shows received as of the shows’ actual achievements. It turns out that Hildebrand orchestrated much of that coverage himself, as evidenced in his overtures to the prominent critic Paul Fechter, among others. Whatever his personal investment in the art may have been, he was always an opportunist most of all.

August Macke, Henri Fantin-Latour, Eugène Delacroix; Bernhard Kretzschmar;

Max Beckmann, Max Liebermann, Conrad Felixmüller, Jean-Louis Forain;

Emil Nolde, August Macke, Camille Corot, Lucas Cranach the Younger.

The works by Nolde and Macke have entered the collection of the Kunstmuseum Bern.

All other works remain in Germany, where their provenance is undergoing clarification.

Here we arrive at Gurlitt’s bizarre relationship with Jewishness. There is something inherently intriguing about the figure of the “Jewish fascist,” for whom things never turned out well. Ettore Ovazza, the prominent Italian Jewish banker, was an avowed supporter of Mussolini until the very end, which came at the hands of SS troops in 1943. Likewise, Hans-Joachim Schoeps, the historian of religion, was the proud leader of Der Deutsche Vortrupp (“The German Vanguard”), an organization for German Jews who supported Hitler, before he was made to go into hiding and then into exile in 1938. On the one hand, these figures are tragic primarily because they comprise a sociological fact. They embody perhaps the most brutal reality of the Nazi ecosystem: the victim turned collaborator, for want of security, profit, or peace of mind. But on the other, they are beguiling because of their troubled psychologies, inner lives defined not necessarily by self-hatred so much as by a cognitive dissonance of the highest possible decibel level. From the beginning, Hildebrand Gurlitt was cast as precisely such a character: a Nazi art dealer who was also partially Jewish, a fount of apparently boundless angst.

But what, exactly, was the nature of his Jewish identity, if he even had one? There is little evidence that Gurlitt ever saw himself that way, and even less that Jewishness ever presented him with a moral dilemma of any kind. If anything, his Jewishness was merely a means of exoneration after the war, when it served a very clear instrumental purpose. During his interrogation by American investigators in June 1945, he told the soldiers about his father, Cornelius, who “was through his mother a born Lewald, of Jewish descent.” The Americans pardoned him of any potential wrongdoing. The case, they wrote, was “dismissed on account of his Jewish blood.” There was, of course, some truth in this: as a half “mischling,” or person of mixed blood, Hildebrand was banned from holding public office — which included the cultural sphere — and often had to use his wife’s name for business dealings. But there is little evidence that Hildebrand actually could have been interned, as he later claimed after the war, in the infamous Organisation Todt, a Nazi slave labor squadron. Full mischlings were indeed targeted, but in the cases of those like Gurlitt, the boundaries were far less clear. In any case, before the war he had been raised as a Christian, and he would not have been considered Jewish under Jewish law. His father, who was half-Jewish by birth, likewise did not show any particular affinity for his mother’s coreligionists. When Hildebrand’s artist sister, Cornelia, committed suicide in 1919, the elder Cornelius blamed her death on the Jewish community of Vilnius, where his daughter had volunteered as a nurse on the eastern front. Her etchings had shown a clear interest in Chagall-like shtetl scenes, and somehow her father saw a causal link. On a fundamental level, it does not seem at all that the experience of the Second World War changed Hildebrand’s relationship to Jewishness in any significant way. He seems to have had no sense of solidarity with other Jews, whose art collections he picked apart in their bleakest hours. Even the wartime plight of a Jew in his own family seemed not to arouse any sense of interest. His sister-in-law, Gertrud, the wife of Hildebrand’s estranged brother, Wilibald, narrowly avoided capture by the Gestapo. Again, there is no evidence that Hildebrand was disturbed.

IV.

By calling their exhibitions a mere “status report,” the curators in Bonn and Bern intended to express their “fact-oriented status approach” to the sale histories of the more than 450 works from the Gurlitt collection on display. In some cases, the original owners of certain items found in the Gurlitt trove have been identified since the collection’s dramatic discovery. The heirs of the legendary Parisian dealer Paul Rosenberg, for instance, successfully fought for the return of Matisse’s Femme Assise (1921), in what is probably the highest-profile Gurlitt restitution case so far. Likewise, Max Liebermann’s Zwei Reiter am Strand was returned to the heirs of David Friedmann, the owner of a sugar factory in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) who was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. But in the case of so many other works on display, their paths into the hands of Hildebrand Gurlitt remain a mystery. The point, in other words, is provenance.

To that end, the German ministry of culture allocated €6.5 million for provenance research, which has been carried out by Dr. Andrea Baresel-Brand, a scholar of cultural heritage at Paderborn University, along with a special task force. Of the more than 1,300 works discovered in Cornelius Gurlitt’s Munich apartment, 1,039 are currently under investigation. Six have been identified as Nazi-looted, but 152 have been identified as “possibly” looted. Additionally, 735 works require “deep research,” which means that many holes remain in their histories, which public presentation may help to fill. Approximately 250 of these works whose full provenances remain unknown are on display in Bonn; approximately 150 of those with cleared (read: non-looted) provenances are on view in Bern. Although Cornelius Gurlitt left the entirety of his collection to the Kunstmuseum Bern, the German government has only allowed art confirmed not to be stolen property in any way to cross the Swiss border. Others will one day make that journey, but some never will.

Consequently, this emphasis on provenance is felt more immediately in the Bonn show, which is both the larger and the more impressive of the two “Status Reports.” Subtitled “Nazi Art Theft and Its Consequences,” its stated focus is on the victims from whom art was stolen, many of them Jewish. To that end, there is a wall of text that greets the viewer near the entrance to the show, which encourages you to look more closely at the explanatory plaques that accompany each work, rather than at the art itself. As this introductory text cautions, there are very few perfect records to see. What we often have instead are ellipses, gaps in the record. Even still, this is what you are meant to see, even if it means crouching down on your knees, bending your neck, and squinting your eyes to make out the small type on the walls. The directors of the two museums involved — Rein Wolfs (Bonn) and Nina Zimmer (Bern) — make no secret about the mediocre artistic value of many of the works on display, some of which are entirely unremarkable tchotchkes from the attics of forgotten ordinary people. “Status Report,” they write, is a different project from a typical exhibition, given that “the aesthetic quality of the works on view is subordinate to their historicity.” We are here for the victims, or so we are told.

This is a noble project. But the victims often appear as footnotes, cast to the side in a production that otherwise focuses on the education, career, and social world of Hildebrand Gurlitt. The Bonn show — at least in terms of its presentation — all too often seems to be in keeping with a recent fashion for exhibitions of art dealers’ lives and collections, such as MoMA’s 2013 tribute to Ileana Sonnabend; the blockbuster “Discovering the Impressionists: Paul Durand-Ruel and the New Painting,” seen in 2015 in Paris, London, and Philadelphia; or “21 rue La Boétie,” a portrait of Paul Rosenberg and his Paris gallery on view at the Musée Maillol last year. In Bonn, the evolution of Hildebrand Gurlitt is likewise the central narrative around which the show is built, though unlike Sonnabend, Durand-Ruel, and Rosenberg, Gurlitt had no influence over the artists of his day.

And by concentrating on Gurlitt’s career, the exhibition’s curators ignore the often more engaging narratives of the collectors whose art he poached. Consider, for instance, the story of Armand Dorville (1875–1941), the prominent Parisian lawyer and collector. By all accounts, his tastes were exceptional, and in 1939 he donated a considerable number of items in his formidable collection to Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs. After the German invasion of France, Dorville fled Paris to his château in the Dordogne, where he died of natural causes in July 1941. The Vichy government confiscated his property, and his vast art collection was auctioned in Nice on four consecutive days in late June 1942. Neither his will nor his earlier bequest to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs suggested that Dorville had intended such an auction, and no effort was made to transfer his possessions to the family members who still stood to inherit the collection. In the end, almost all of his family would be deported and murdered in April 1944. The Dorvilles, like so many other haut-bourgeois, assimilated, republican “israélite” families of the French prewar era, would essentially cease to exist.

Three works from the Dorville auction ended up in the possession of Hildebrand Gurlitt, although he was not himself present for their purchase. Now they are on view at the Bundeskunsthalle. One of these works — Profile of a Lady (1881), by the lesser impressionist Jean-Louis Forain — was purchased by the art dealer Léopold Dreyfus. The other two — Lady in White, also by Forain, and Female Rider on a Horse Galloping to the Right, by the more significant Constantin Guys — were purchased by a woman recorded in the auction ledger only as “Béatrice, Hôtel Royal, Nice.” The exhibitions’ joint catalogue speculates that the second buyer could have been either Béatrice Ephrussi de Rothschild or Béatrice de Camondo-Reinach, two wealthy Jewish collectors of the period. The first hypothesis is impossible, as a quick Google search would have confirmed: Béatrice Ephrussi had died in Davos in 1934, eight years before the Dorville auction ever took place. Béatrice de Camondo, however, may very well have been the buyer: she was a famed equestrienne, and the Guys drawing in particular — of a woman on horseback — would fit with other items that she and her husband, the composer Léon Reinach, had amassed during their troubled marriage, which ended in a bitter divorce in 1942. Dorville had also represented her briefly in 1936, when she opened the Musée Nissim de Camondo, her late father’s own exquisite bequest to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. In any case, the important point is that Gurlitt may have acquired these three pieces as the result of twin persecutions: first of Dorville, and then of Léopold Dreyfus and Béatrice de Camondo (if indeed she was the mystery buyer). Dreyfus, after all, filed a complaint in December 1945 listing more than 70 works of art that German soldiers had stolen from his home in the Yonne. Although the Forain in question is not among those items, he may have also been forced to hand it over to ensure his survival. For her part, Béatrice de Camondo — along with her ex-husband and their two teenage children — was murdered in Auschwitz, scarcely two weeks before Soviet forces liberated the camp.

The two portraits by Forain in “Status Report” date from the early 1880s, and they are archetypical products of France’s anxious Third Republic, artifacts of a world that had no idea of its impending demise. In Profile of a Lady, his subject gazes off into the distance, locked in some kind of continuum. So it was for this woman, whoever she was, and so it was for Armand Dorville, who acquired this portrait. Yet in a section nominally devoted to Dorville and his story, there is little on display that tells us much about him. Why is his portrait nowhere to be seen? Where is the explanation of the now-vanished Parisian world of the israélite, of which he was an important pillar? As the catalogue notes, detailed minutes were kept on the outrageous 1942 auction that dispersed his beautiful possessions in direct violation of his written will. Why aren’t excerpts of these included in the main display? Without things like these, cumbersome though they may be, we begin to lose sight of precisely the person we came to see — not the dealer Gurlitt, not the artist Forain, but Dorville, the collector, the victim. As in the case of Georges Mandel, “Status Report” subordinates his story to that of the Nazi collaborator who ended up with his pictures. It really should be the other way around.

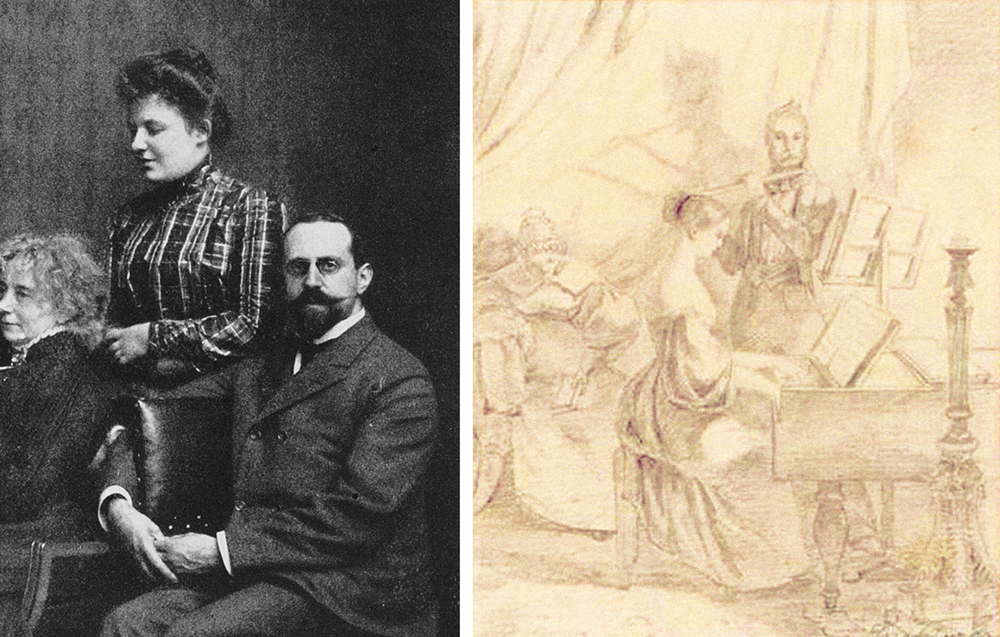

To that end, the most devastating of the victim stories in the Bonn exhibition is without question that of Henri Hinrichsen, the owner of a famous classical music publishing house in Leipzig. Like many wealthy, assimilated Jews, Hinrichsen never quite accepted that the rise of the Nazi regime meant that his life was in danger. In his eyes, his patriotism, his philanthropy, and, well, his Germanness meant that he had nothing to lose. Then came Kristallnacht, in November 1938: the offices of his company were ransacked, the company was “Aryanized,” and Hinrichsen’s private art collection was sequestered. Only then did he begin to acknowledge the hostile reality, departing for a life of exile in Belgium with his wife, Martha. Gurlitt purchased four pieces from the Hinrichsen collection: a painting by Camille Pissarro, which he then flipped a week later at significant profit; a drawing by the Austrian painter Moritz von Schwind, which he then sold to Hitler’s Führermuseum, again for a tidy gain; a portrait of George Frideric Handel, which has never been found; and, finally, a drawing by the German Romantic painter Carl Spitzweg. Gurlitt wrote to Hinrichsen in January 1940, assuring the old man he had deposited the money into his account — albeit an account that had been frozen by the state and that Hinrichsen could not access, which Gurlitt likely knew. In what appears as the cruelest of Gurlitt’s schemes, he then demanded that Hinrichsen pay the costs of transporting the pieces to his own gallery: “I assume you will acknowledge that this is absolutely normal practice,” he wrote.

Right: Carl Spitzweg. Das Klavierspiel. c. 1840. Drawing. 6½ × 5 in. Ex. coll. Cornelius Gurlitt; recommended for restitution to the heirs of Henri Hinrichsen.

Martha Hinrichsen died in Belgium after having been denied an insulin infusion because she was Jewish. Henri himself was arrested by the Gestapo on September 13, 1942, and was deported to Auschwitz, where he was sent to the gas chamber immediately upon arrival. After the war, their surviving descendants were particularly keen on recovering the Spitzweg drawing, Das Klavierspiel, which depicts a bourgeois couple playing music in a sumptuous salon and apparently held a certain amount of sentimental value for the family. When asked by the Hinrichsen family lawyer about the drawing’s whereabouts, Helene Gurlitt, Hildebrand’s wife, insisted that it had been incinerated in the Dresden fire. The family then gave up. Cut to November 2013, when Der Spiegel interviewed Cornelius Gurlitt, her son. For years, the Spitzweg had hung in the hallway of his Munich apartment, just as it had hung in his mother’s house, the magazine reported. As the late Martha Hinrichsen, Henri’s granddaughter, said in an interview: “It gave me a chill when I read that.”

This Spitzweg drawing, later recommended for restitution, has an unmistakable darkness: behind the piano-playing wife is the lightly shaded silhouette of her husband, but the shadow has two slight horns that give him the air of a demon. But the drawing is no longer merely “art.” Unavoidably, it is also a piece of property, a musical scene once owned by a man who published music and who was murdered because he happened to be Jewish. Finally, it is also the evidence of a crime: the coordinated deceit by a family that profited from the abject wrongs of history and apparently felt no compunction whatsoever to correct them, even decades later. Given the fate of Henri Hinrichsen, no item in “Status Report” condemns Hildebrand Gurlitt and his family more forcefully than Das Klavierspiel. At long last, after two whole exhibitions that only touch on the realities of this collection, we see who Gurlitt really was.

But you could be forgiven for not noticing. The drawing Hinrichsen owned encapsulates the essence of what matters: Gurlitt’s petty opportunism, his betrayal, his lies. Yet Hinrichsen’s story — not unlike that of Armand Dorville — is presented in Bonn as merely an anecdote in the life of the dealer. The exhibition design features a central path that follows the chronology of Gurlitt’s life, and the Hinrichsen case is little more than a nook off to one side. Accompanied by a small photograph of Henri, the story is explained in one simple paragraph that concludes, of the Spitzweg, “Hildebrand Gurlitt and his wife Helene repeatedly denied that they were still in possession of the work.” This is clearly no attempt to apologize for Gurlitt, but consider the choice of emphasis. If the show is about victims, why is there not more about this Leipzig family and less about Gurlitt? We could do with far fewer photographs of Hildebrand and his siblings in World War I uniforms and far fewer vitrines that display the books he studied as a young man. In their place, we might have images of the Hinrichsens around the dinner table, a picture of their business’s old Art Nouveau headquarters, and perhaps even a photograph of the death camp to which Henri Hinrichsen was condemned.

The art alone is not enough. It is what remains of Henri Hinrichsen and his wife, yes, but a single drawing completed around 1840 does not at all convey the world in which they lived and died. They can never be brought back, but their world can at least be remembered, if only to reiterate that at no point was their fate inevitable. At some point, the details of Gurlitt’s relationship to Das Klavierspiel and, indeed, to all the other pieces on display in Bonn and Bern become irrelevant. Why should we care about the personal evolution of a dreadfully mediocre art dealer whose animating principle seems to have been profit and professional advancement? This is the question that “Status Report” never answers.

V.

On the train home from Bonn, I finished a novel called The Oppermanns. First published in 1934, it is an astoundingly prescient portrait of a bourgeois, assimilated Jewish family in Berlin at the beginning of a slow, inexorable decline into humiliation and annihilation. Written by the great Weimar polymath Lion Feuchtwanger (1884–1958), who belonged to exactly such a family, the narration periodically lapses into commentaries on the nature of the inferno in which it is set. “During those days people learned to lie in Germany,” Feuchtwanger writes. “Their speech was deceitful and so was their silence. They got up with a lie and they went to sleep with a lie.”

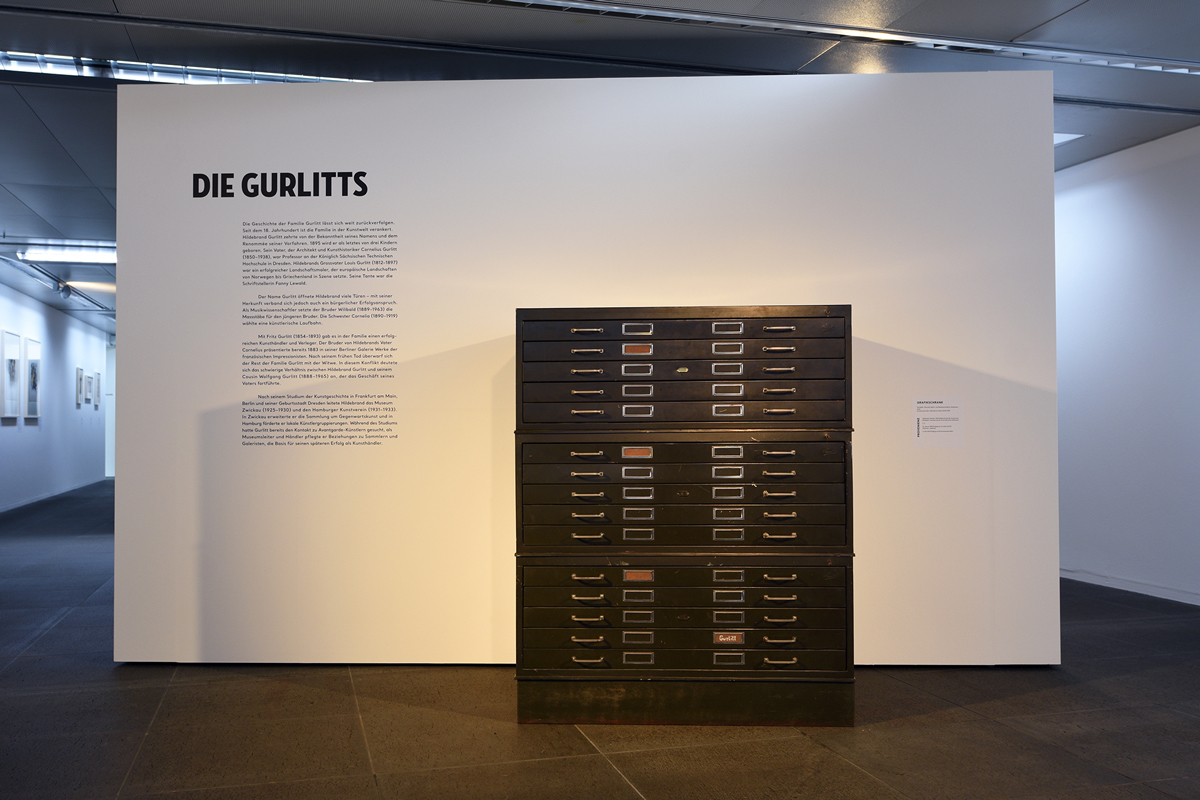

Hildebrand Gurlitt went to sleep with a lie for the rest of his life, successfully reinventing himself as the director of the Düsseldorf Kunstverein, which he led from 1948 to 1956, when he died in a car crash. Almost more difficult to comprehend is his son, Cornelius Gurlitt, who inherited Hildebrand’s cache and slept with lies for decades on end. “Do you occasionally take pleasure in what you have?” his sister, Renate, once began a letter to her brother. “It sometimes seems to me that his most personal and valuable bequest has become the darkest burden on us.” In any case, it never proved a burden dark enough to warrant offloading, for sister or for brother. The paintings and drawings remained hidden away in an apartment right in the center of town, many jammed in the drawers of a filing cabinet.

The filing cabinet has traveled too. It was one of the last things I saw in Bern, which represented the end of what had become my Gurlitt odyssey, to two shows in two underwhelming museums in two provincial cities in two different countries in two consecutive weeks. When I saw it, I must admit, I was aghast: all that time and all that money spent for this, to end up before the filing cabinet that had been used by the reclusive son to protect the hoard of the morally bankrupt father. What purpose does it serve to exhibit this, except to embellish a drama devoid of any real substance, and to distract from what has always been unseen? What counts about the art on view here is that Georges Mandel was murdered in the forest, that Armand Dorville’s collection was auctioned off without his consent, that Paul Rosenberg never lived to see the return of his Matisse, that David Friedmann lost his beloved Liebermann, that Martha Hinrichsen was denied an insulin injection on account of being Jewish, that Henri Hinrichsen was gassed at Auschwitz.

We should be reminded in the most visceral way possible of what happened to these people, of whom Hildebrand Gurlitt took deliberate advantage. They, in the end, are all that matters. How and why the Gurlitts slept with lies is their problem.