II. Athens & Thessaloniki

by Marina Fokidis

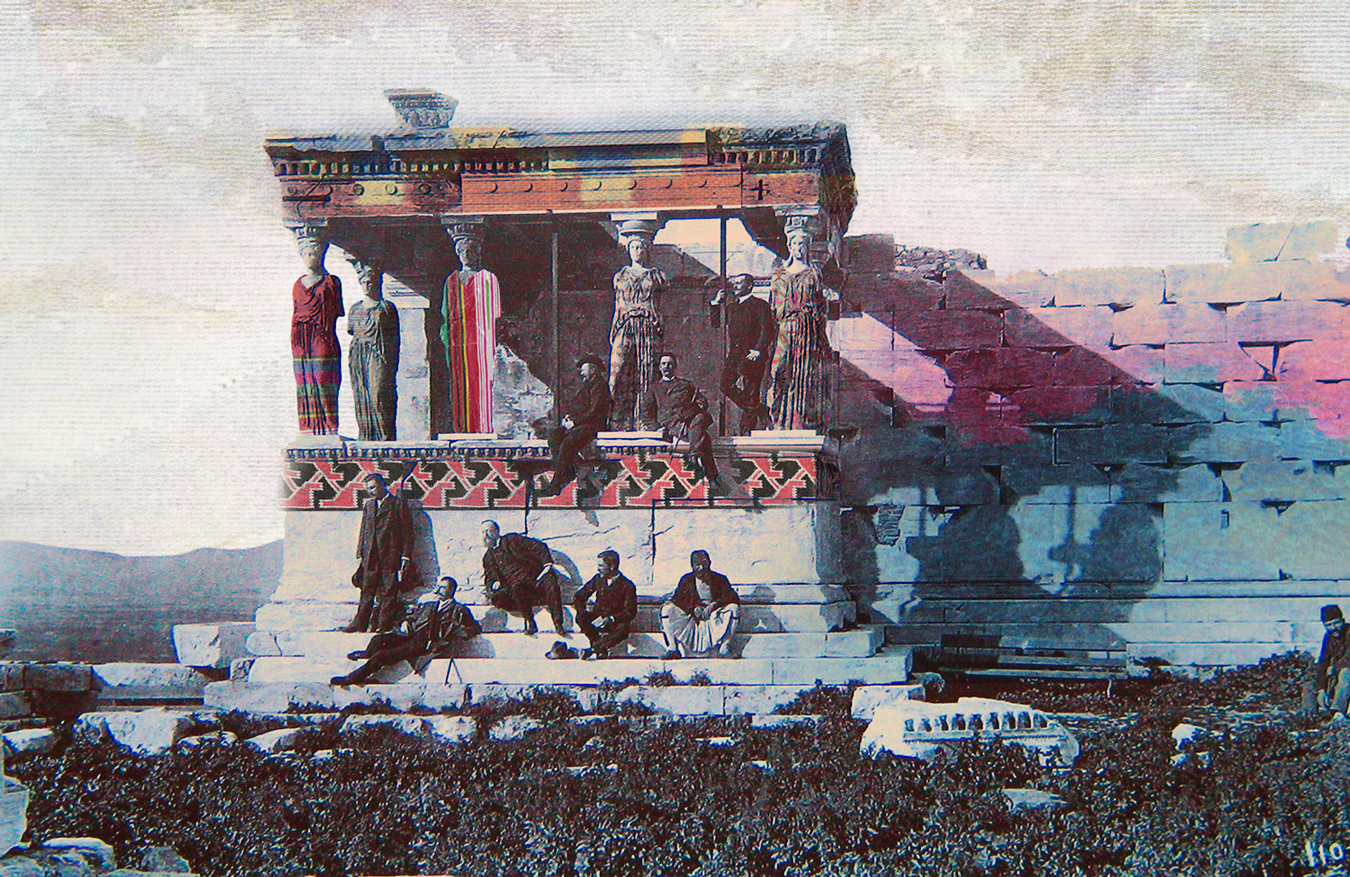

Andreas Angelidakis. Carpetized. 2013.

This is an excerpt from Even no. 2, published in fall 2015.

Devoid of humans, the city looks like a ghost of itself. The camera in Marina Gioti’s film As to Posterity (2014), seen earlier this year at the Thessaloniki Biennale, travels through the streets of Athens during different seasons and different times of the day—three years’ worth of travel, at the peak of the economic crisis. We pass through empty streets and parks, cinemas and shops, urban voids. The only apparent sound is that of the natural environment. Birds are still singing, but their song gives little hint of what has happened to the city’s other, human inhabitants.

Is this the near future, or an allegory for the present? An end or a beginning? The landscape Gioti presents in As to Posterity is more oneiric than real — despite the fact that it is neither staged nor digitally manipulated. The despair and solitude evoked by the urban desert coexist with a sense of a wishful utopia, as if this is the Athens that might appear when the place is free of its main destroyers: we humans ourselves. Without losing its hard edge, formed as it is of images from the symbolically and literally ruined Greek capital, the film seems like an ode to an impossible place. That is already here.

“Anyone who lived through the days of December 2008 in Athens knows what the word ‘insurrection’ signifies in a western metropolis,” write the members of the anonymous French collective The Invisible Committee in their new book To Our Friends. Even the Christmas tree standing in Syntagma Square was set ablaze. Seven years later, we can see just where that insurrection got us. “What the Greek case shows us,” The Invisible Committee concludes, “is that without a concrete idea of what a victory would be, we can’t help but be defeated. Insurrectionary determination is not enough; our confusion is still too thick. Hopefully, studying our defeats will serve at least to dissipate it somewhat.”

Unemployment, pay cuts, constant demonstrations, instability, fascism, injustice, corruption, lack of resources, a newly radicalized class of people just sacked, frustration, mandatory migration, displacement, uncertainty, lack of welfare, loss of hope, elections, re-elections, power manipulation, fatigue, exhaustion, paralysis, capital controls…. The everyday here in Greece is like a leaky vessel. And while the water level is dropping, ideas on how to survive in the postcapitalist desert do not come easy. The situation is ruthless, and there are no easy solutions. All possible outcomes entail a degree of discomfort or a price to be paid. The Greek crisis confronts us as a harsh reality that is here to stay: a difficult episode of an unknown duration, which we all have to learn to survive as best as possible.

The defiance and anger do not limit themselves to national borders. It spreads beyond Greece, beyond nations, beyond territorial and economical communities. Europe seems to be in the process of turning itself into a museum, just as an immense flux of refugees arrives, many of them coming ashore first in Greece before continuing to Western Europe. The continent’s prevailing political and economic system, and the doctrines that undergirded them, no longer function — and yet at the same time no promising alternative solutions seem forthcoming. Time seems limited, the need for a collective introspection urgent. The word crisis has become an easy tag for everything: it vitiates the need for serious thinking, and that is nothing less than immoral. So our greatest responsibility during these times is to think with the deepest precision — to think of causes and possibilities, to analyze facts, to open up a constructive environment for knowledge, even amidst the difficult context produced by the real restrictions imposed upon us.

The art scene in Greece has gained greater international attention over the last several years. “Holiday in someone else’s misery” was a slogan that the artist Phil Collins was circulating on T-shirts in a similar situation, during the first Tirana Biennial in Albania in 2001, and that might be the case here also. But only partially. Greek artists and art professionals have been sensitized by the fragile situation around them, and they urgently need to communicate with the rest of the world. More than that, art has offered a way to endure the harshness of everyday life over the last years while not losing our dignity. In a country whose citizens oscillate between despair, lack of resources, uncertainty, turbulence, anomie, disbelief, corruption, and chaos, adopting an imaginative distance from daily events can sometimes be more effective than any gestural form of destruction. Art in Greece today no longer aims to offer an imitation or critique of reality, but much more a means of departure — from the everyday toward the realm of the imaginary. Seven years ago we were hurled violently away from our prior certainties, and we still live at a “point zero” from which we can find no escape. How then can we formulate a new perception of our lives and actions: a new ontology? Art, I hope, can serve as one of the terrains to reflect on our will and our strategy to fight for a more inclusive present, and a somehow livable future. If one can still count on the future, that is.