Order and Progress

from Even No. 4, published summer 2016

Artists, musicians, intellectuals: in the years after 1964, when a junta took power in Brazil’s swooping new capital, much of the country’s cultural clan went into exile. Lina Bo Bardi stayed. The Italian-born architect, whose commanding art museum hangs over São Paulo’s Avenida Paulista, found little work for two decades. The military government closed her museum in Salvador. But Bo Bardi could not go back to Italy, not when her adopted country had given her art and life its form. “When one is born, one chooses nothing,” Bo Bardi said later. “I chose to live in this place. That’s why Brazil is my country twice over.”

She had a point. Even has taken a special interest in Brazil since our first issue, in which Silas Martí assessed the young artists of today’s Rio and São Paulo against five hundred years of colonial anthropology. Last winter, he reported from Curitiba on art’s entanglement with Operação Lava Jato, the biggest corruption scandal in Brazilian history. Now, for this fourth issue, Martí undertakes a grand, urgent survey — a personal reckoning as much as a historical study — of Brazil’s artists and art institutions as the country reels from an impeachment, a recession, and an epidemic. Artists in past decades faced harsher obstacles than these. But it is tough not to fathom this latest trial as a stinging deferral of the future.

It’s true, the BRIC ascendancy was oversold; the world, though, will still have its way. Elsewhere in this issue, Kanishk Tharoor examines the art of Asia’s combustible megacities — Shanghai, Mumbai, Manila, Jakarta, each of them dwarfing the storybook capitals that nurtured European modernism — as the latest chapter in a long history of financial and artistic entwinement. (The Dutch masters, too, worked in an emerging economy.) H.G. Masters guides us through the hardening landscape of Istanbul, where urban reconstruction has gone fist in glove with rising authoritarianism. Zoë Lescaze shuttles between New York and London to see how established museums are introducing foreigners’ voices: the guest list is changing, though the velvet ropes are still intact.

At the start of this peculiar millennium it was fashionable to guess where the future would come from, to wager on which single city would fuel culture as Paris did in the 19th century, or New York did in the 20th. That was a model from a more stable time. It now seems clear that the 21st century is not going to have an epicenter — just a sprawling network of regions and peoples, booms and crises, in which exile has no true meaning and from which no place really withdraws. “I believe in an international community of interests,” Bo Bardi once said, “in a concert of all the private voices.” Such a concert, she understood, could only be staged in a new kind of architecture. It also necessitates a new kind of art magazine.

—Jason Farago, editor

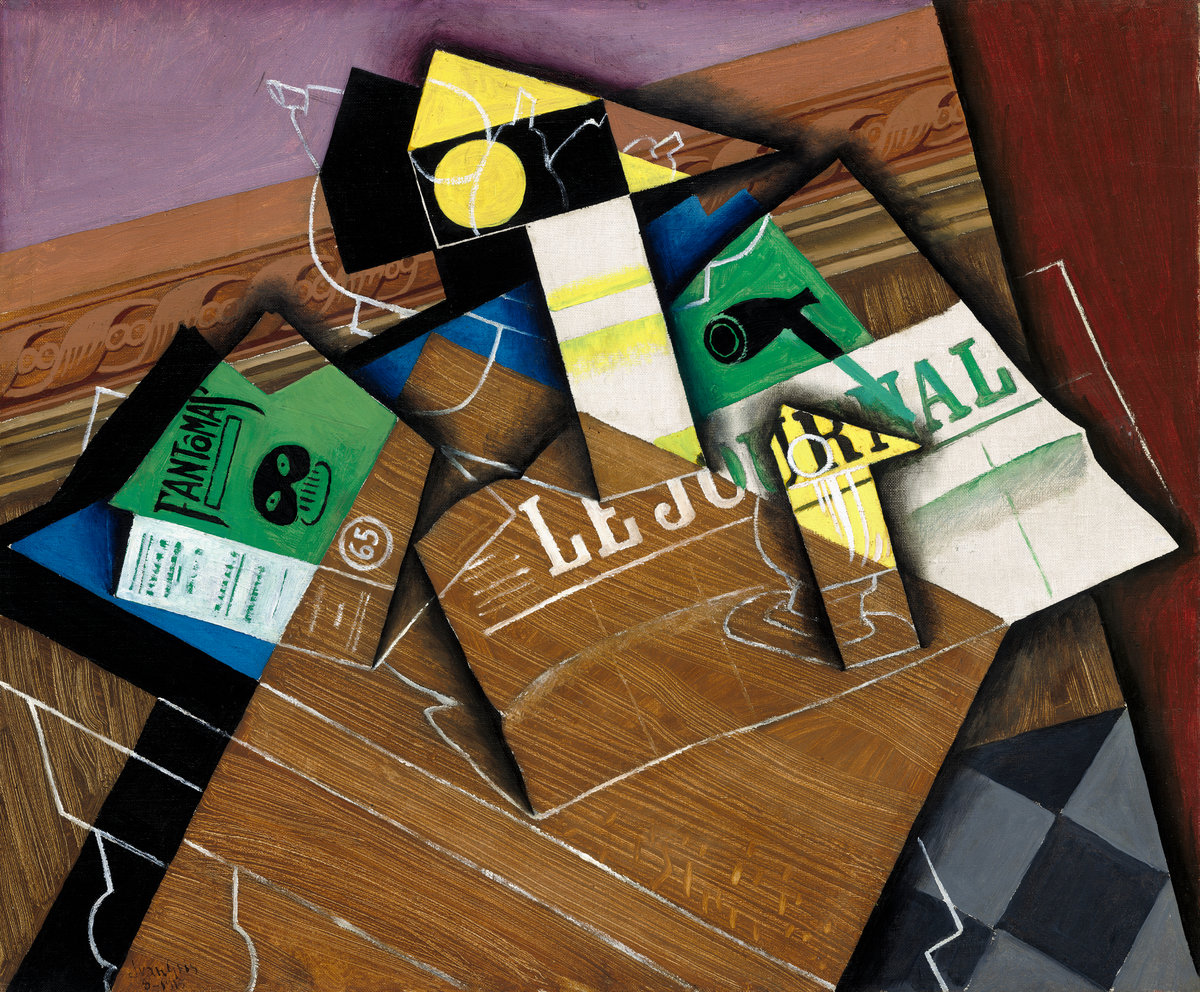

After a few drinks the surfaces all blend together: the wood grain of the table, the tiles on the floor, the wallpaper with its false crown moulding. But you can still, after a long day at the café, do a little light reading. Le Journal, for example, a sensationalist newspaper full of true or not-so-true crime, and a cheap paperback: one of the hack-penned Fantômas books, whose monthly horror stories had a whole cache of avant-garde fanboys.

For Juan Gris, a media junkie in the big city, painting and especially collage were the ideal formats to represent a world of mass communication. In that, he offers a model for navigating our own landscape of information. When old forms seemed to be losing distinction, when the proliferation of content got to be too much, synthetic cubism barred both anti-media snobbery and the easy comfort of the image stream. To suture, to strike, to fashion anew: there is more than one way to aggregate.