In God We Trust

from Even No. 6, published spring 2017

When I was 27, lost, at a difficult pass, I wrote a mash note to a certain architect and told him that I would bail on New York, give up everything, if I could come work for his firm in Beijing. I needed a new life, I was stubbornly convinced, and how would I find it in America, country of a lapsed century? I flew to meet him, breathing in the Chinese smog as if it were ether, and I got the job. Yet the next day, dodging bicycles beneath Rem Koolhaas’s CCTV Tower, I knew I was going home. Thinking of places as the future or the past suddenly seemed juvenile; the future happens everywhere, and America wasn’t so troubled anyway.

Well, maybe I got it wrong. The freak election of Donald Trump — despite the weakest popular mandate of any president since the introduction of universal suffrage — is about to test like never before the proposition that the future is bigger than any nation. Certainties do seem to have crumbled in a day: here in New York, still dazed, we make very dark jokes about camps and climate change, and struggle to conceive of a superpower canceling itself. In four years, assuming the nukes stay sheathed, we might very well no longer recognize ourselves. But as Ma Yansong, another Beijing architect, tells my colleague Lynette Lee in an interview for this issue, four years isn’t even long enough to build an apartment block, let alone a future. Four years: an eternity or an instant? Either way, it’s all so unprecedented that neither apocalyptic predictions nor assurances of continuity seem entirely credible.

This is an uncommonly American issue of Even. Down in Washington, Lauretta Charlton revisits the Smithsonian’s heralded museum of black history and culture, whose forward-dawning narrative seemed on point in September but soured two months later. Up in New York, Allison Hewitt Ward picks apart our assumptions about art’s political efficacy, and wonders why we seem most confident in culture when it fails to make an impact. The role of art in times of crisis is not a new question for us, of course, and there are foreign lessons for this age of American unexceptionalism. This issue also plunges us into thrumming, wildly expensive Luanda, where, as Chloé Buire shows us, music is all about who you know: Angola’s hip-hop stars drink with oil ministers in beachfront clubs, and MCs who rap about nepotism end up behind bars.

It is a new year. The shame has not subsided. But there is no dropping out of this; somehow, my fellow citizens will have to face down a threat to American cohesion as great as any since the end of the Civil War. One of the enduring lessons of art is that the times mark you whether or not you desire it, and that dreams of withdrawal are as foolish from the president’s foes as from his make-it-great-again nostalgists. Run as far as Beijing and you will have escaped nothing. Artist or autocrat, you cannot take a pause from history.

—Jason Farago, editor

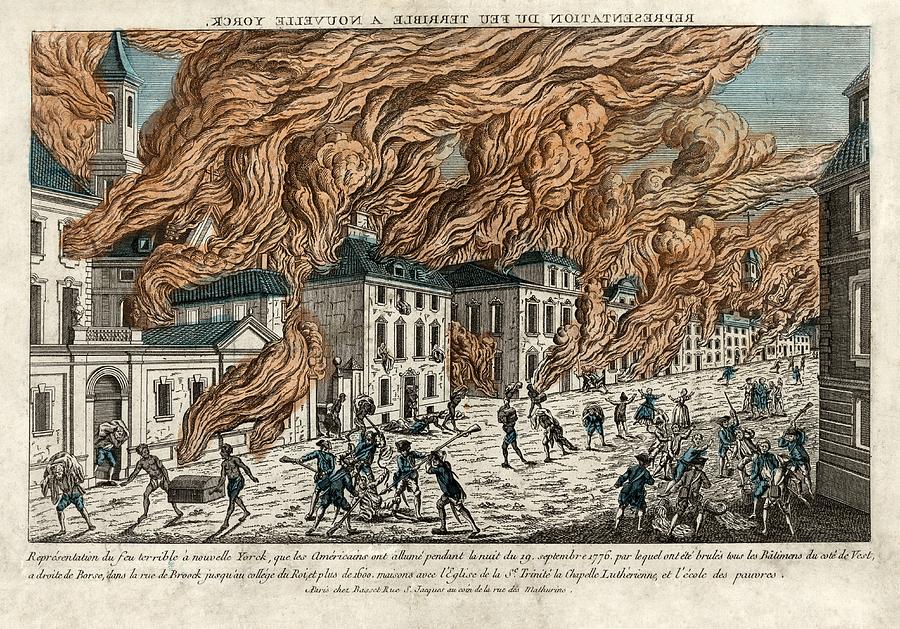

It kept getting worse that summer. Over in still wild Brooklyn, King George’s troops had routed the revolutionaries: slaughtered us at Red Hook and Gowanus, and locked us up — as seditionists, not captives of war — on prison ships in the East River. General Washington was constrained to retreat north, to Westchester. And then, whether by arson or accident, occupied Manhattan went up in flames in September of 1776. The declaration we made that July cost us our houses.

When this Prussian draftsman pictured the destruction of Manhattan, he would not have had much hope for the rebellious Americans. The colonies’ trade hub was gutted; the promises made on July 4 were unlikely to be kept. What New Yorkers had then — what we, their heirs, have still — was a brief season’s taste of public freedom, impossible to get out of your mouth even when you can’t find bread. We have known tyranny before, but hopelessness is not an American art; the ideals of the Revolution, unmet but unquenchable, have not died yet. In five years we won the war.