Portfolio

Jane Chang Mi

One Sunday in 1946, a US Navy officer greeted the parishioners of the little church on Bikini Atoll and gave them the good news: they were, like the Israelites before them, about to make an exodus. The ring of islets in the South Pacific was to be cleared only temporarily — and the atomic bombs to be tested there were not malicious, the Bikinians were assured, but engines of perpetual peace. Weeks later they had been relocated, and by the end of the year a fireball swelled over the atoll, the first of 67 nuclear tests in a zone the US called the Pacific Proving Grounds. No one ever went home, needless to add. If you aggregate the firepower of all the bombs over Bikini, it endured more than one Hiroshima attack a day.

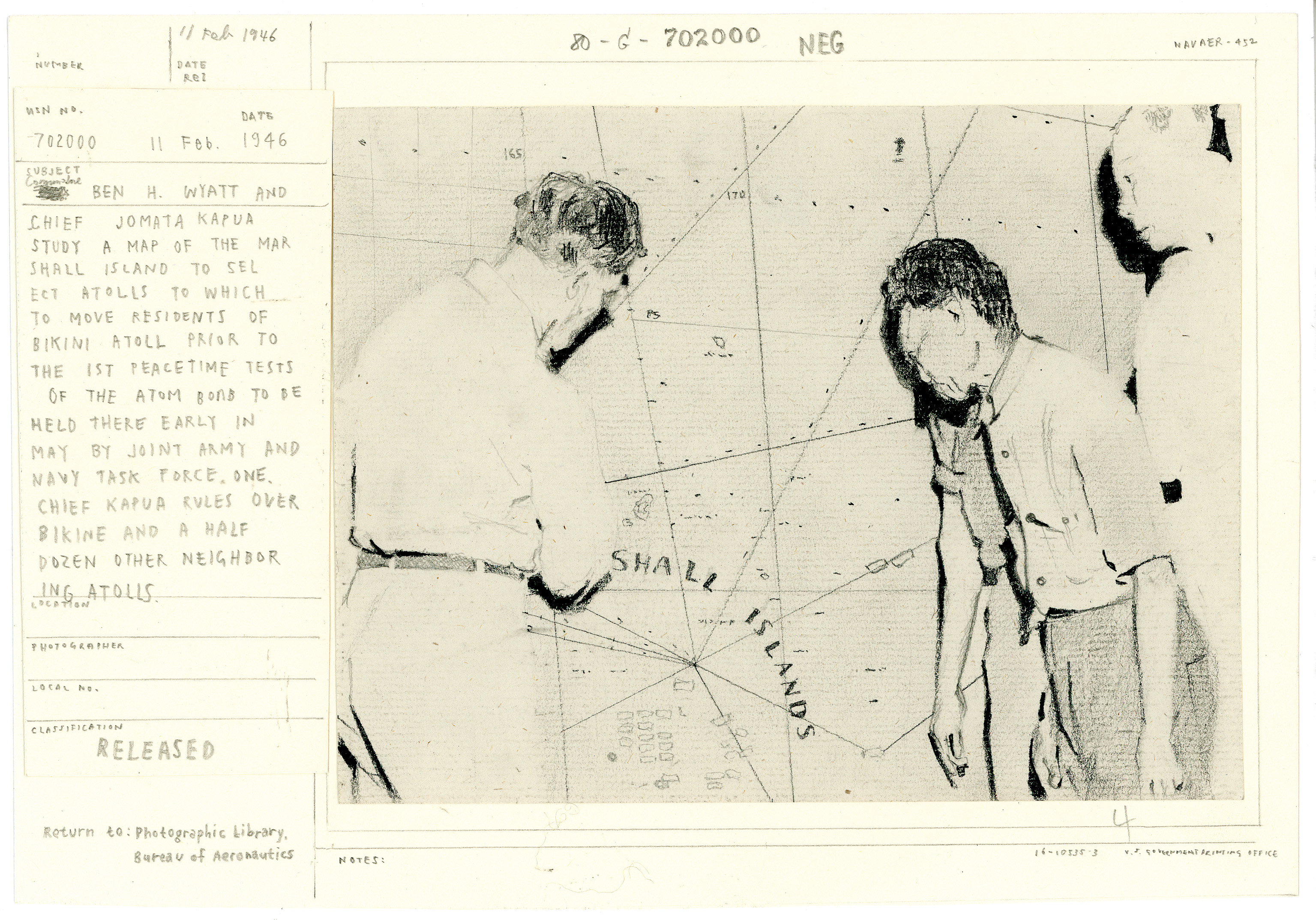

Recently the Hawaii-based artist Jane Chang Mi went through the government archives of some of those tests, whose code names — Nutmeg, Butternut, Hickory, Redwood — were comically unrelated to the Micronesian flora they blasted. The explosions were endlessly photographed, and the archives bulged with mushroom clouds, topographic maps, radiation measurements; there was only a handful of photos of the islanders, with flippant captions on the back. “News that their home atoll had been selected for the 1st peacetime test of the atomic bomb came as a surprise to the Alap natives,” reads the legend on one of the declassified pictures—which Mi painstakingly sketched for a recent exhibition in Honolulu that explored the twin weapons of images and armaments. Earlier, in a series of pseudo-idyllic photographs in French Polynesia, she had bayoneted the Pacific escapism of perfumers and bottled water purveyors, selling a “purity” accessed via international airport. But here, more murkily, Mi’s drawings were scrambled with historical documents and an overhead view of a nuclear site facing rising sea levels. Where the water laps higher each day, you’ll need more than prelapsarian visions to keep you dry.

Mi was born in 1978 and lives between Los Angeles and Honolulu. She trained as an ocean engineer at the University of Hawaii before turning to art. (She’s a throwback, maybe, to an earlier, Renaissance tradition of artist-scientists.) If the collective heritage of the Pacific informs her photographs, videos, and installations, so do her maritime research and her scuba training; for one recent project she dove down to the wreck of the USS Arizona, which lies beneath Pearl Harbor. What constitutes the natural world, and what lies in the realm of history, is a fraught matter in her art, and in Mauna O Wakea, whose grainy views of astronomical observatories belie the bitter disputes about the mountains they stand upon, the distinction may actually be moot. What you find when you look up to the heavens is all a matter of the world below.

In the 7th century, the Polynesian explorer Ui-te-Rangiora traveled south from Rarotonga in a war canoe, and is said to have reached a continent covered in snow. Perhaps, perhaps not; but when Mi made the same voyage recently on a triple-masted ship, the frozen land was not what it was. Her windswept, anxious video Deception Island takes us to an atoll off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, whose expanses of snow appear less white than ashen. A chinstrap penguin, alone in the gray wasteland, stands on the beach as the storm drives in, but though he flaps his wings and cranes his beak, he plants his webbed feet as firmly as Friedrich’s Wanderer. This is a sublime of another kind, as empty as the one traversed by the last century’s polar explorers, but remade in ways we can just begin to see. The penguin is not flapping to keep his balance, or to signal to mates. He is flapping because Antarctica is too hot.