Fortress of Solitude

by Lauretta Charlton

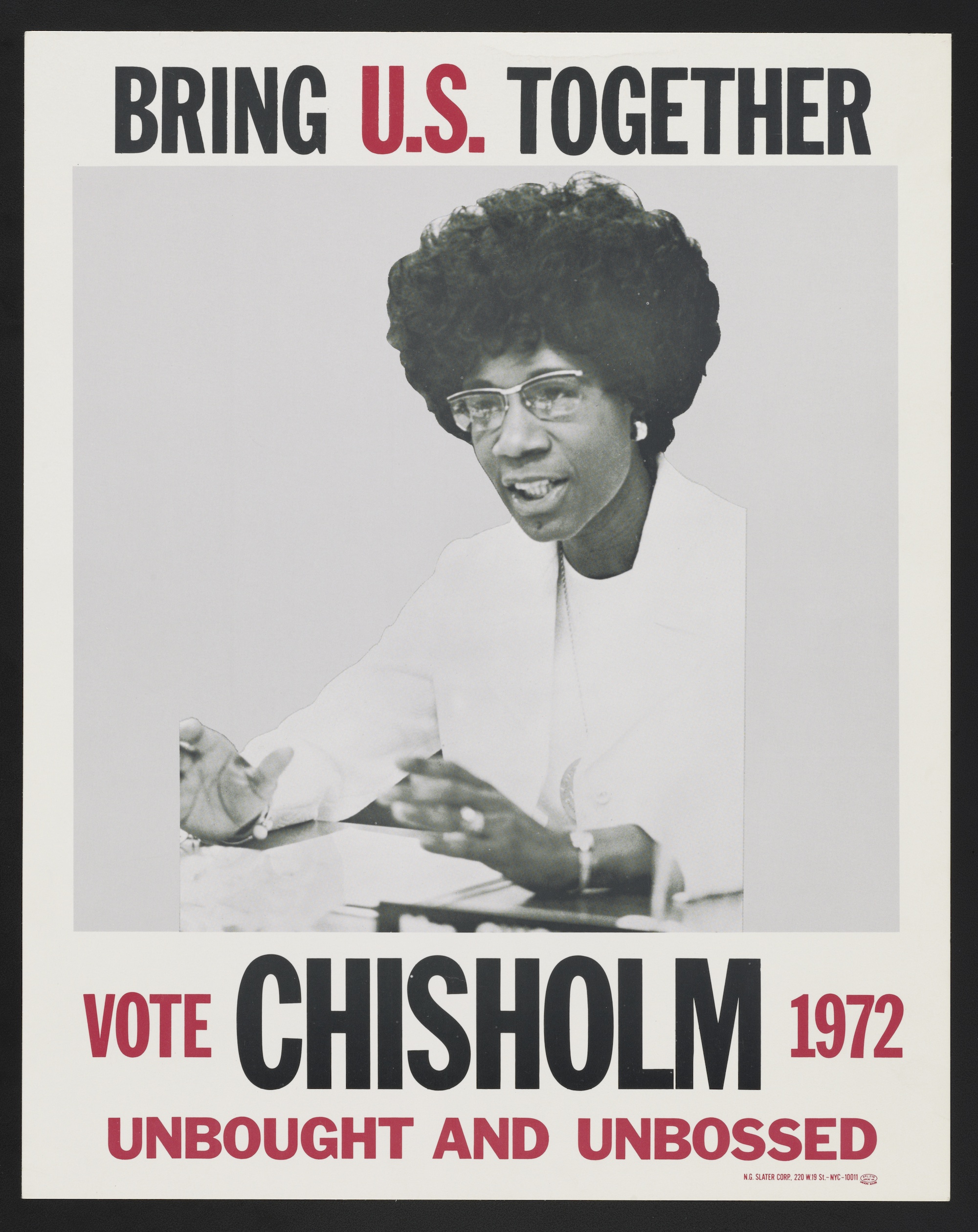

A poster from the presidential campaign of Rep. Shirley Chisholm. 1972. University of California, Los Angeles.

This article appears in Even no. 6, published in spring 2017.

Just before his assassination in 1865, President Lincoln established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, an agency tasked with integrating freed slaves into southern society after the Civil War. Like so many good deeds, its history was short-lived. The legislatures of the southern states, newly reintegrated into the US, responded by enacting restrictive laws that expressly aimed to deny former slaves their freedom. The Ku Klux Klan began to intimidate and terrorize the black population in the south, and by 1872, facing a lack of funding and growing complaints about federal overreach in states’ affairs, the program was abandoned.

I thought about the Freedmen’s Bureau on a recent visit to the new National Museum of African-American History and Culture. It reminded me that institutions meant to promote racial unity in America have historically encountered stubborn, even violent resistance from its citizens. That the museum opened in the final year of the second term of America’s first black president is made all the more remarkable by the fact that it will mature under Donald Trump — a man who made his political reputation by questioning Barack Obama’s citizenship, and who won this country’s highest office after running the most explicitly racist presidential campaign since George Wallace in 1968. The museum, a branch of the Smithsonian, stands right on the National Mall, housed in a handsome building designed by the Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye and clad with ornamental bronze filigree. It has been thronged with visitors since opening last September, and its location, just at the base of the Washington Monument, bespeaks the institution’s mission to put a more inclusive version of black history at the center of American life. But the collective hand-wringing about how exactly that should be done, and for whom, is only getting started, and under President Trump the job will be far more urgent, and far harder.

Like many African-Americans, I had already been won over by the museum’s basic premise: to celebrate the complicated and vibrant history of black people in America. Lonnie G. Bunch, the founding director, has done a fair job of this. The permanent collection displays a balance of horror and glory through multimedia installations, video footage, artifacts, photographs, historical documents, and countless bite-sized blurbs either affixed to walls, screened on glass, or featured in timelines. There are peaceful art galleries with paintings by Clementine Hunter, Romare Bearden, and Ed Clark, and musical displays where Mahalia Jackson sings “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” or Run-D.M.C. raps. The heartbeat of the museum, though, is in the history galleries, which wind up a series of ramps separated by large-scale video projections contextualizing four centuries of African-American history.

The Middle Passage, the transatlantic slave trade, the colonial era, and the creation of whiteness are staged in the basement, where the ceilings are low, the rooms are dark and crowded, and the light is dim. (The environment is meant to reflect the brutal circumstances of the 18th century, though I found the cramped quarters, instead of inspiring contemplation, ended up encouraging visitors to rush through the galleries.) From there one zigzags forwards through time, encountering a handful of large-scale exhibits along the way. We see a typical plantation cabin occupied by slaves, then a Jim Crow-era train car with segregated seating, then a guard tower from Louisiana’s notoriously brutal Angola Prison. Nat Turner’s bible has prominent placement. So too, in an isolated room with restricted viewing, does the coffin of Emmett Till, a black teenager lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after he allegedly whistled at a white woman in a grocery store. Objects, rather than images, carry the strongest resonances of violence; the permanent exhibit, in what I found to be a missed opportunity, does not prominently depict the ugliest moments in our history. Graphic moments like rapes, mutilations, riots, and lynchings are downplayed. Bunch has said the museum “needs to be a place that finds the right tension between moments of pain and stories of resilience and uplift.” But in the main, he and his team opted for the latter.

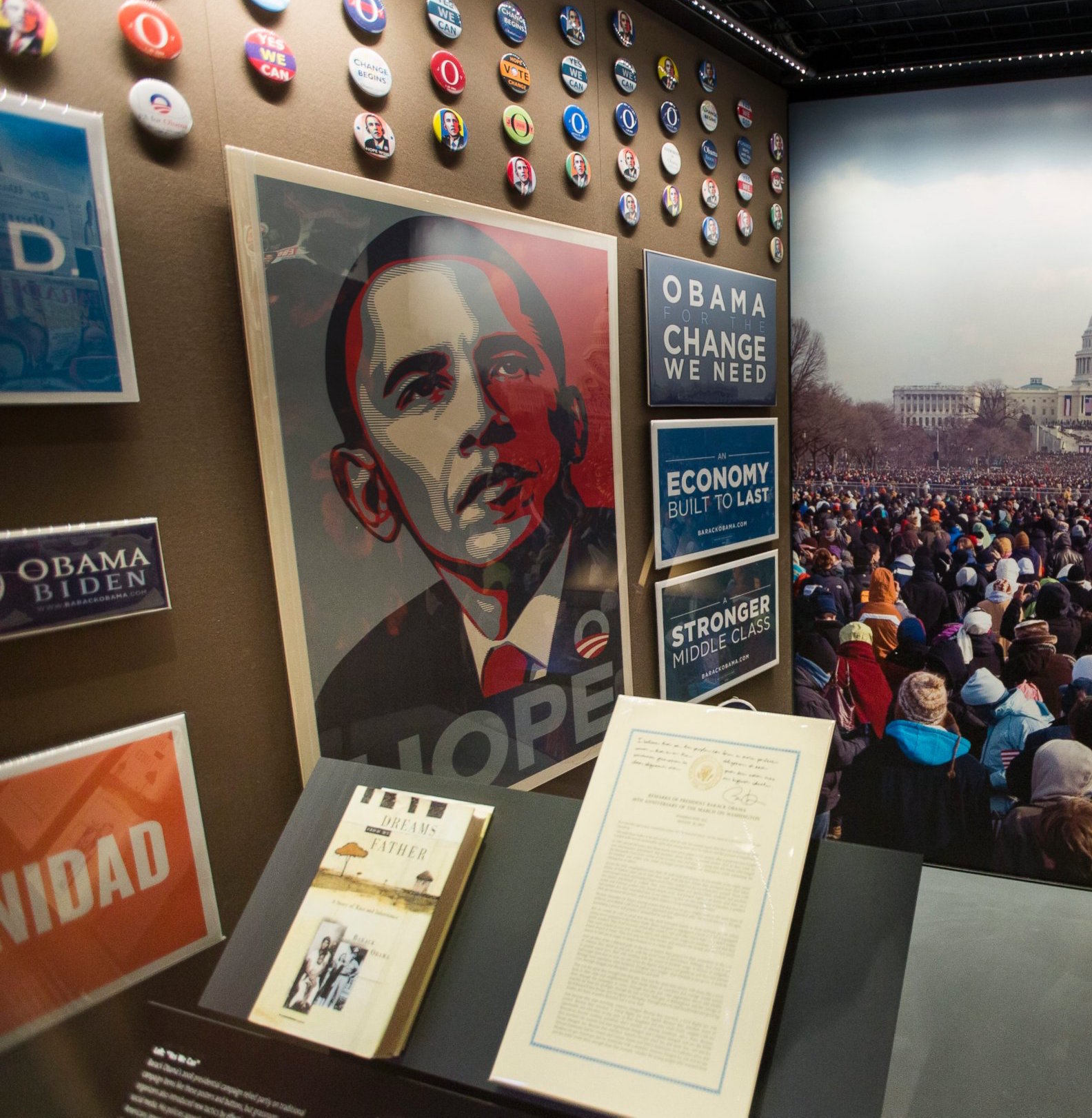

Eventually the gloom gives way; the higher one travels through the galleries, the more buoyant the atmosphere. Not surprisingly, the permanent installation ends with images of Barack and Michelle Obama with their children, waving at crowds of happy Americans, of all races, chanting Yes We Can! Eight years ago, this mantra of a little-known, mixed-race junior senator from Illinois seemed to embody the best of American values. It affirmed that the American dream was in fact intended to, and did, benefit all Americans. But those halcyon days quickly gave way to the familiar and disappointing reality of racism and inequality in America. The backlash to Obama arrived almost immediately, and Donald Trump is the apotheosis of its success. Bunch and his curators had planned for an America that was ready to face its failures, and ready too to celebrate the progress it had made towards a more equal society. Instead, the divisions that have defined the country’s most sadistic and cruel periods seem more secure than ever. The majority of the visitors I saw in the museum were black.

Even with its flaws, I could not help but feel protective during my visit of Adjaye’s spaces and the contents they held. Before November, the museum had been for me an object of joy and curiosity. In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, its existence, like the Freedmen’s Bureau, seems fragile, even threatened, by those who shamelessly glorify an incomplete version of the past. Beyond its mandate to celebrate and tell the story of the black experience, the museum’s most difficult task is to make the case that black history is still being written and deserves to be told. It won’t always be easy. Two years ago, in Charleston, South Carolina, a young white man sat in a bible study group at a black church for more than an hour, only to open fire on the congregation and massacre nine people. That horrific moment is now a part of black history, too, and the museum must find a way to share it with the world. There is no right way of doing this. It only needs to be done.