Portfolio

Li Ran

A new country needs heroes; it needs villains, too. In the fledgling People’s Republic, Mao’s government began screening movies on mobile projection units that toured the rural interior, but only a few films were good enough for the Chinese people. Hong Kong productions were banned, as were films made on the mainland before 1949; instead came melodramas and propaganda pictures shot on elaborate sets at facilities like the Changchun Film Studio. You remember the glorious patriots, intrepid martyrs, mothers giving their sons to the revolution — but there were stock villains as well, played by actors in whiteface, hamming it up as dastardly American troops or agents of “the superpowers.” Switch on Bear’s Prints, a spy thriller from 1977, featuring arrogant Russians unprepared for the Chinese sneak attack. “Colonel, may I be frank,” says a bewigged Soviet operative. “We are confronting enemies who have lived through the Cultural Revolution!” Enough to give any komissar pause.

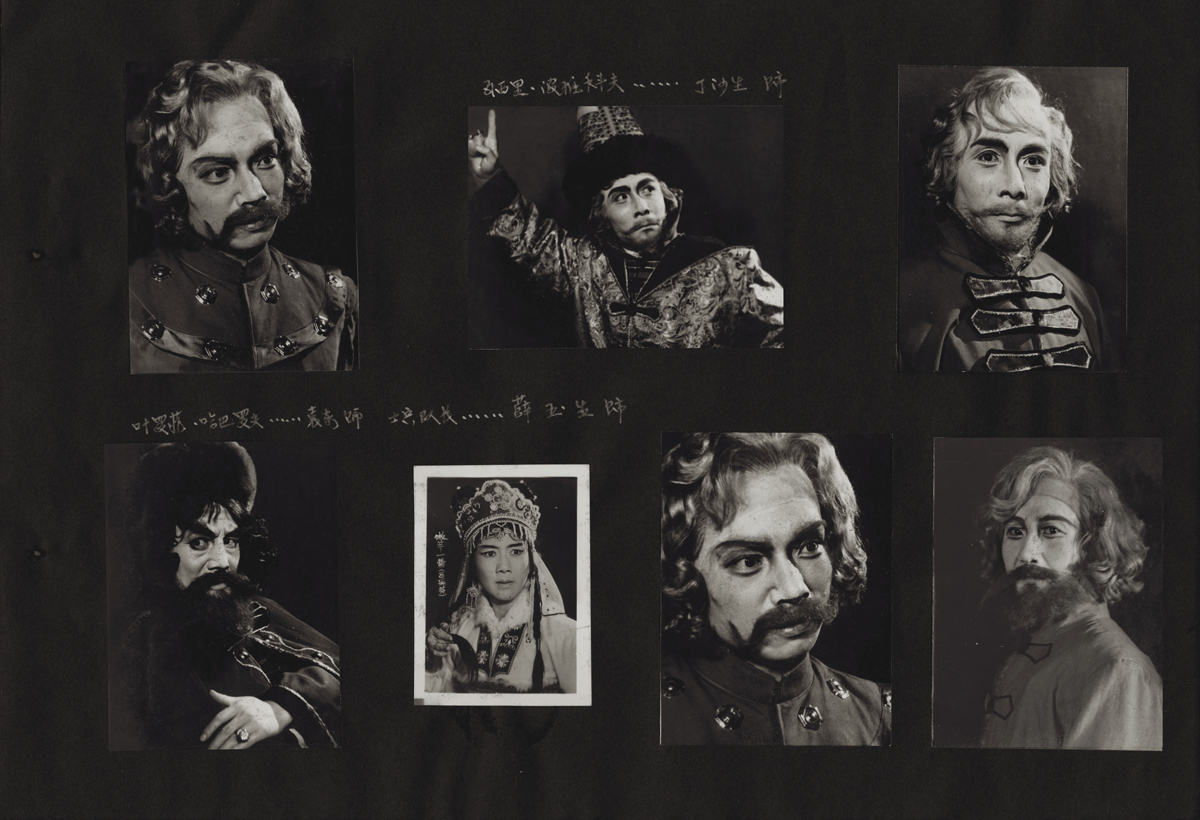

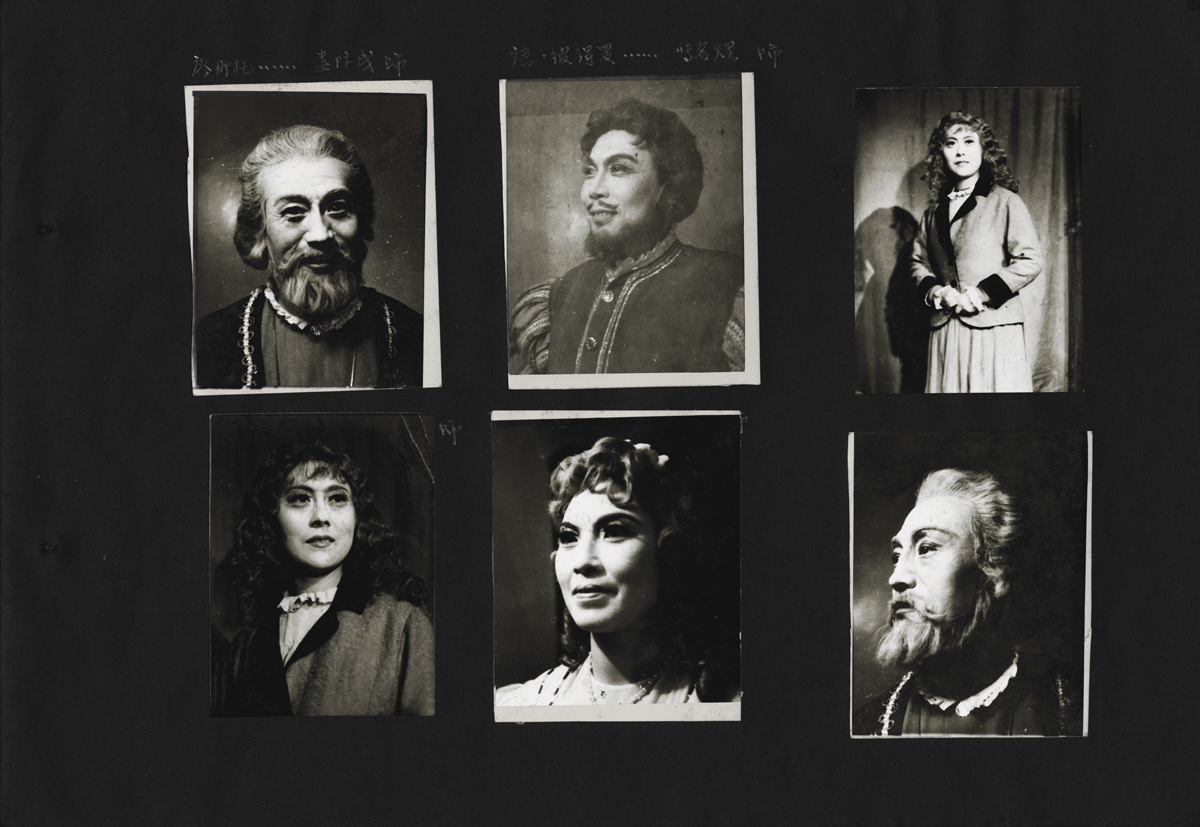

The young artist Li Ran spent much of the last year digging through the archives of Chinese film studios and drama ensembles, and he unearthed dozens of photographs of these clumsy, shady outsiders, wearing baroque costumes and heavy stage paint. Some Han actors specialized in these villain roles, but many more were from China’s Muslim minorities, or else of partial Russian ancestry. The photos gave rise to the wry video installation Retransformation of the Supporting Roles: a caustic marriage of slapstick comedy and historical redress, in which six actors throw themselves into pantomimes of drunk sailors, corrupt missionaries, and Yankee soldiers going down in a hail of bullets. Once no one outside of China would have seen these impersonations — but the art world we think is global can be as pitiless as Jiang Qing’s script doctors. For the jetlagged viewers of the latest biennial, you must string up your history and make it dance.

Li was born in Hubei in 1986 and studied oil painting at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, China’s oldest art school. His father, Li Min, was a painter too — a fact evoked in his early Another “The Other Story,” which juxtaposed Dad’s oil paintings with a precious black-and-white film, starring the younger artist as a Chinese modernist coming to terms with Cézanne. It was one of several projects in which role-playing (channeling past lives, in some; playing avatars of himself, in others) served to make the confusions of today’s China a bit more endurable. In the first of two films known as I Want to Talk to You, But Not to All of You, Li sits with a European curator, spelling out his biography and the aims of his art ahead of a retrospective. But the same footage, with a bit of editing and some easy cuts, turns art history into psychobabble — and Li’s self-promotion becomes blithering about phantoms of the past.

A new country needs heroes; but world powers have stricter budgets, and heroes are very expensive. In Same Old Crowd, Li’s lavish and disquieting film installation of 2016, a dozen amateur actors play roles we can’t quite decipher, looking into the distance with twitchy, wary expectation. Their clothes, fur wraps and batik shifts and hemp sandals, suggest we are somewhere other than the big city — holdouts from modernity, perhaps, in a province where the generic towers of the new China are rising a bit too slowly. A crow’s wings beat; the cast look up, as if perceiving an augury; and suddenly comes the sound of hundreds of birds, squawking and flapping, harbingers of a future in which a hundred flowers may finally bloom. But the birds never land, no matter how long they look; they are a foley artist’s flutterings, a gimcrack effect from the propaganda studio.