Portfolio

Ana Vaz

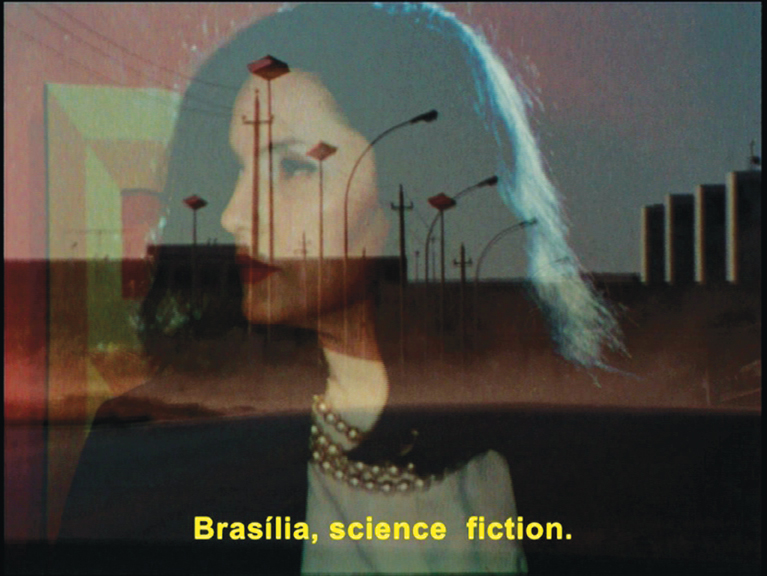

“Brasília is artificial,” wrote the novelist Clarice Lispector: “as artificial as the world must have been when it was created.” But we humans were only fashioned six days into the world’s creation, and as Eden deformed its inhabitants, Brazil’s new capital too crafted a new sort of person. Its highways and superblocks, its bewildering horizontal expanse, can hardly be traversed on foot; streets recede in the city Kubitschek built, and social life takes place indoors. Brasília ruptures the savannah, and quietly, subconsciously, ruptures lives too. It sprawls and sputters, transfigures your days and movements, and remains as mystifying as the maternity ward looks to a newborn. Lispector: “When I died, I opened my eyes one day and there was Brasília.”

Three years ago the artist Ana Vaz traveled to the rugged west of Brazil, to backlands as wide and arid as those the capital now occupies, and found herself in a quartzite pit whose cliffs glowed white under the sun. What she filmed there cohered into A Idade da Pedra (The Stone Age), a strange, chimerical vision of urban construction in which modernism has the cast of prehistory. As pickaxes sing out and blocks of quartzite shatter, Vaz’s camera pans a full rotation over the quarry — which seems, thanks to a little digital trickery, to lie beneath the arches of some grand modernist ruin, wrenched out of time. Vaz had already made an impressive early work, Sacris Pulso, that interwove home movie footage of the delirious capital with scenes from a Lispector adaptation, but A Idade da Pedra went further: here the boundaries between nature and society, geology and architecture, seemed no longer to hold. Dig, and you could find the modern city of ten thousand years ago.

Vaz was born in Brasília in 1986. (Her father Guilherme Vaz, whose music sometimes backs her films, was a pioneer of sound art in Brazil who lived and collaborated with peoples of the lower Amazon.) She studied in Melbourne and Paris, and her peripatetic education goes some way to explaining the global reach of her films and performances, and the diverse materials they absorb. In Occidente, a dreamy enjambment of Brazilian and Portuguese history, grainy 16mm footage of peacocks, surfers, and Sunday lunches gives way to Google Street View renderings of Lisbon’s Praça do Comércio, the regal central square built after the famous 1755 earthquake. The Enlightenment ideals the square embodies are tied up with the colonial missions that embarked from its adjacent port — and in fleeting shots of china and porcelain, silver and furniture, the Old World’s commodities seem on the verge of crying out their foul play. More recently, in the sublimely assured Há Terra! (Land Ho!), Vaz’s camera races through the long grasses of the Brazilian backlands, where a young woman — one we first encountered in A Idade da Pedra’s uncanny quarry — keeps evading view. The color-sapped 16mm stock may put you in mind of early ethnographic cinema, but here there is no privilege from being behind the camera. If this is indeed the Anthropocene, we are all both hunter and hunted.

“To be ethical is to be anxious,” Vaz says in one performance. But anxiety has benefits; when you’re unsure of your footing, you have no choice but to stay on the move. In The Voyage Out, her most recent work, Vaz brings us to a brand-new speck of an island in the Pacific, not far from Iwo Jima, that arose from a volcano in 2013. When the tsunami strikes, when the power plant melts down, still somehow creation goes on beyond our anthropoid imaginings. On the island, plants have begun to sprout. Gannets have landed and laid eggs. The earth is a crafter of its own.