Picture for Women

by Iona Whittaker

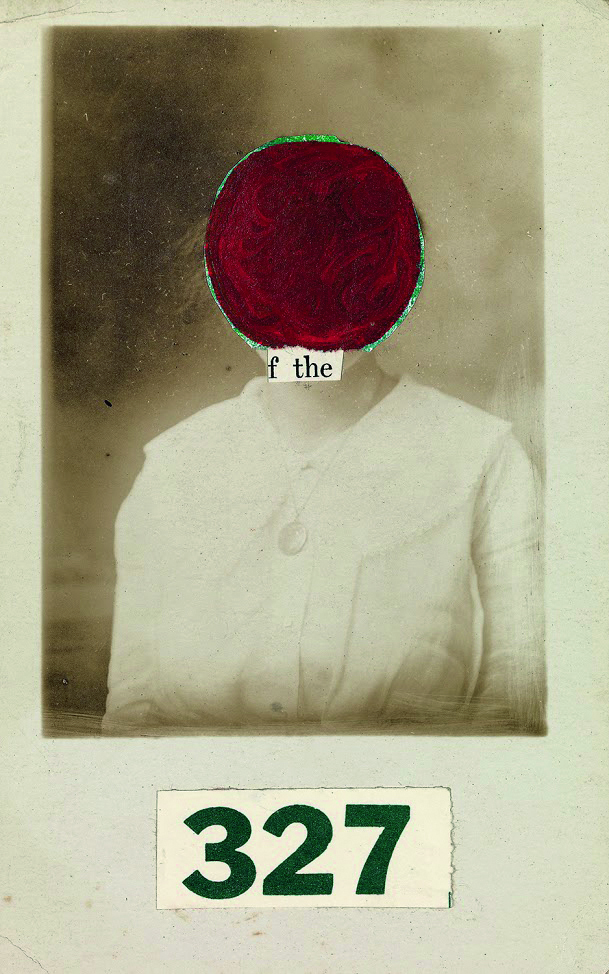

Robert Seydel. F the 327. 2008. From Book of Ruth. Siglio. 2011. © Estate of Robert Seydel.

Book of Ruth, a fictional journal composed by the late artist Robert Seydel, shares with this magazine an origin in The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even — Duchamp’s infamous, unfinished painting on glass. Seydel conceived of a work between art and literature, featuring “Ruth” as the bride among the bachelors Sol (her brother), Joseph Cornell, and Duchamp himself. The resulting 78 pages of poetic, verbal and pictorial collage, published after Seydel’s death in 2011, are attributed not to him, but to her. “Ruth is the artist in the book,” Seydel declares in the preface.

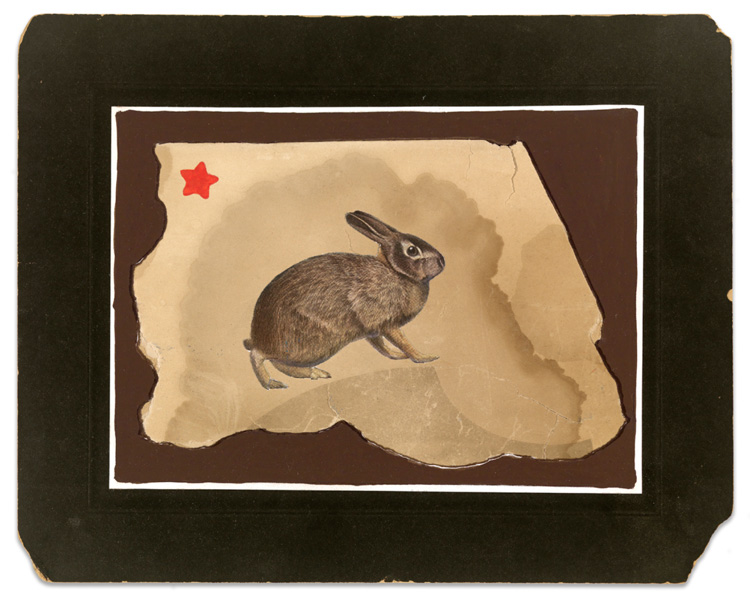

Seydel’s strange work went on view this summer at the Queens Museum in New York, and the journal pages, along with related small compositions, are radiant and eccentric: photographs vie with rough scraps of newspaper, painted patches, stick figures, spontaneous typewritten passages, pasted numbers, bits of advertising, and floating orbs or cartoon eyes in startling red. The hare recurs as an emblematic creature. Seydel’s work is ripe with the mixture of pathos and fierceness which haunts successful collage. And yet he disavows authorship. Seydel’s alter ego, Ruth, is the author — she is based on Seydel’s real aunt, Ruth Greisman — and she is not alone. Duchamp himself was sometimes Rrose Sélavy. The potter Grayson Perry is also Claire. The writer JM Coetzee has delivered lectures as Elizabeth Costello. (There’s also the artist Joe Scanlan, whose avatar Donelle Woodford is both of a different gender and a different race, but perhaps we should leave her be.)

One tends to think of an alter ego as an opportunity — a person one “would be,” beyond the limits of what one is. But Seydel didn’t use Ruth to imagine a more exciting life than his own. Quite the opposite, he admits: “Silly, isn’t it? You’d think you’d want to invent a heroine with more tooth to her.” He found in the life of his aunt, a bank clerk and Sunday painter living in remote Queens with her shell-shocked brother, a vessel to explore the quiet potency of a figure barely noticed by society. As a woman, Ruth was “further along the line of powerlessness”; her private status and domesticity, her position outside the mainstream and exterior to Seydel’s own self, signaled possibility for him.

Seydel dismissed the idea of “self-expression,” preferring the full conception of another self. In Book of Ruth, one finds the private universe of a man’s imagination layered onto his sense of someone else, and then expanded still further to conjure a third, female persona projected forcefully onto the page — for Seydel, a process of “opening outwards...into the air of art itself.” In a complicated dynamic, Seydel eventually found his own state blurred with Ruth: “I thought originally I wanted to inhabit another person; now she inhabits me.” Ruth also seems puzzled at times by her own expression in the Book, perhaps wavering between this and another, “ordinary” world where disbelief prevails. And her perceived drabness is essential as a source of her power. Seydel enacts a valiant art against the forces of obscurity, against the judging of books by their covers, or artists by their outward lives, or indeed women’s roles as limited. Ruth triumphs. Through her, we see Seydel cocooning in an effort to emulate the “quickness and interiority” he admired in female artists and writers, and to better grasp his own creative tendencies.

In an homage to the women in his life, the book is dedicated to Seydel’s mother, who, alongside the real Ruth, first introduced him to “the location of art and its importance as an activity.” Ruth is and was real, then, in more ways than one, and lest Book of Ruth be seen merely as a charming or sentimental work, its medium alone overpowers any such risk. Seydel loved what he called “contaminated” or “contradictory” artists; similarly, the strength of collage lies largely in its resistance, its ability to force disparate things together. Not unlike life — even apparently simple lives — incongruous fragments are cut from the procession and pieced together. Ruth’s unfettered making, her strange or humble fantasies, streams of consciousness and sudden artistic marks, are in their way resilient and impure. To quote another’s poem, this Ruth — and that Seydel, and even perhaps Duchamp, Coetzee, and their compatriots too — found herself unique, adept, and “somewhat more free.”