I. New York

by Allison Hewitt Ward

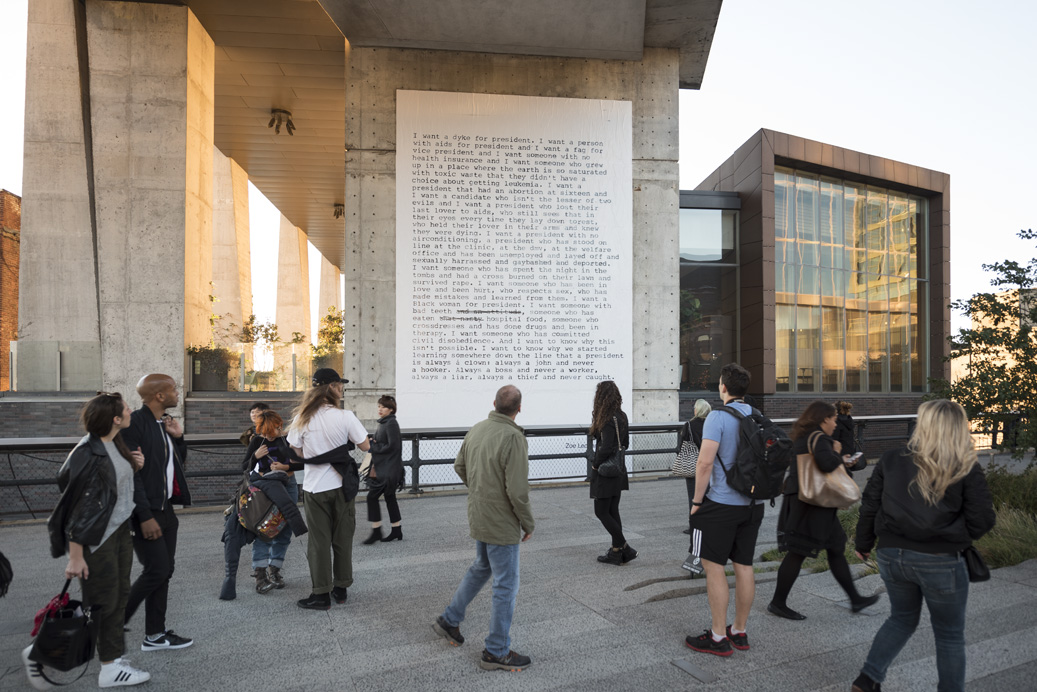

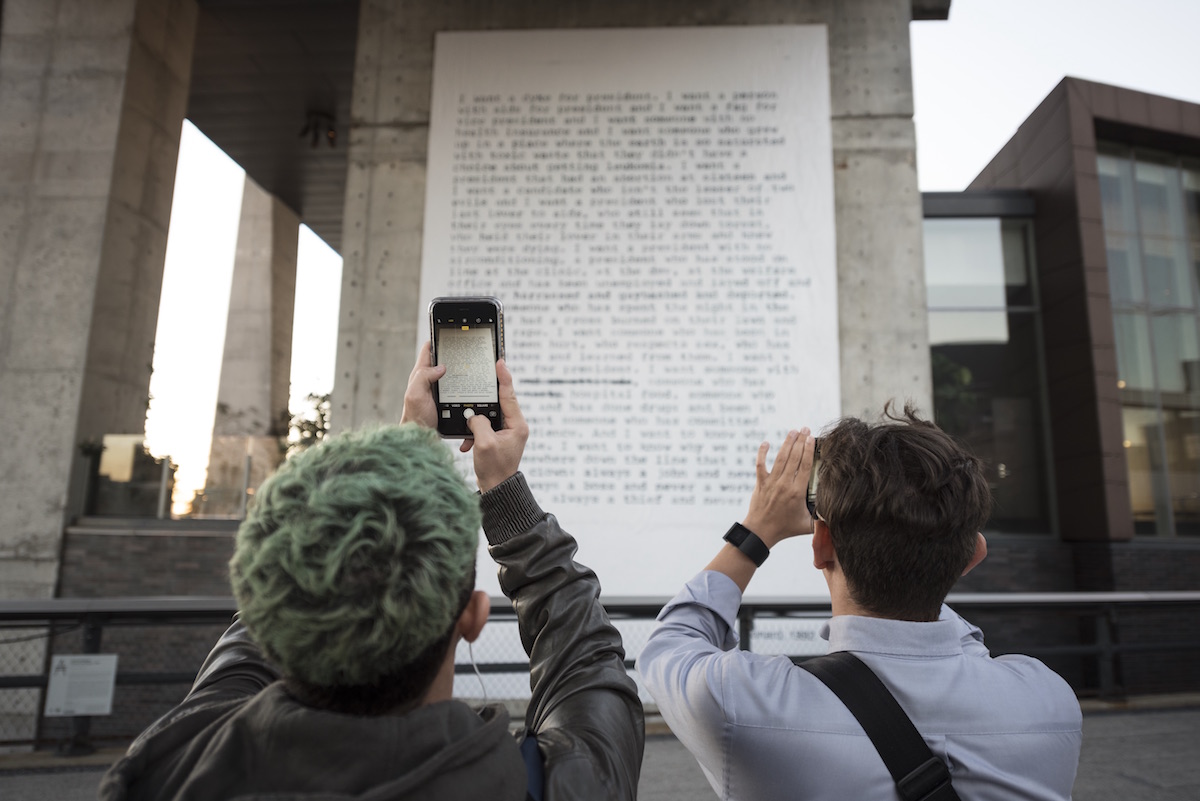

Zoe Leonard. I want a president.... 1992 (recreated 2016). High Line, New York.

Courtesy Friends of the High Line. Photo: Timothy Schenck.

Simon Denny: Blockchain Future States

Petzel Gallery, New York

September 8 – October 22, 2016ƒ

Decolonize This Place

Artists Space, New York

September 17 – December 17, 2016

Zoe Leonard: I want a president...

High Line, New York

October 11, 2016 – March 2017

When the New Zealand artist Simon Denny opened his exhibition at Petzel Gallery in early September 2016, the US’s political future seemed all but certain: Hillary Clinton would be the next president. The long march of neoliberalism that she embodied would continue more or less uninterrupted. Donald J. Trump, for artists and academics and others pigeonholed as “coastal elites,” was little more than a punch line — an absurd foil to the faux progressivism of Hillary Clinton that helped make it seem just a little less faux.

Denny is a relentlessly present-tense artist, and his exhibition opened with a sculpture of a giant Pokéball, conscripting summer 2016’s biggest trend as an introduction to his brave new world. A figure of the Pokémon franchise’s “Ash” character beckoned with a welcoming grin and exuberant fist to the sky. Today’s hunt, however, was for Bitcoin, not Pokémon. Attractive Plexiglas standees featuring characters straight out of Cupertino and a soothing, disembodied male voice invited the eager student to the rear of the gallery, where a video presentation delivered a history of economic thought, from the dawn of capitalism to a present teetering on the verge of a new economic era. The ultra-slick installations — immaculately designed pedagogical zones filled with the kind of jargon you’d expect to see at a trade fair — were selling us something, complete with the self-assurance and twinge of sarcasm that came with knowing we’d already bought in. Information and instructions abounded. It was immediately clear that this exhibition was to be read, not interpreted, like text on a flat page.

Amid last fall’s atmosphere of political confidence and economic fatalism, Denny offered a palliative. “Blockchain Future States,” an exhibition chockfull of dioramas and displays advertising financial technologies, ascribed a newness and radicalism to the future we all already anticipated. The world to come would be defined by an increasingly globalized economy and digital networks. It was to be ushered in by a change of degree, not of kind, an intensification of forces at work since the end of the Second World War. The future is dematerialized finance capital, Denny accepted, but maybe that’s not such a bad thing? There was even a computer mining Bitcoin (presumably) in the gallery — that future is already here, though the liberation promised certainly is not.

As in his recent exhibition at MoMA PS1, and in common with many of the young artists he showed alongside at last year’s Berlin Biennale, Denny tried to make a virtue of the ease with which his art could slip between contradictory positions. Was his Bitcoin show-and-tell a view onto a techno-financial utopia, rejecting the old nation-state model of centralized capital in favor of a liberating vision of global, decentralized currency? Or was it a piercing satire of the Silicon Valley belief in that very notion? It was both, even if it ultimately succeeded at neither. And yet when so many young artists interrogate the past or simply borrow and remix its forms, there is something refreshing in Denny’s insistent foresight. He uses his small sampling of historical source material wisely: the board game Risk, so emblematic of modern imperial warfare, was reformatted for an era of withering nation-states and new emerging networks. In the various iterations of the game installed at grand scale throughout the galleries, the tensions between what was and what will be became palpable. The two-dimensional globe and rigid playing pieces are already inadequate frameworks for the world to come.

As we all know now, that’s not how the story ends. The lynchpin of Denny’s entire artistic career — the assumption that the reign of neoliberalism would continue unchallenged — has come loose. Ruptured first by Brexit, the neoliberal settlement has now been cracked wide open by a halfwit reality TV star with an outsize Twitter following who seems dead set on burning down the agencies, policies, and diplomatic norms of the modern United States. Trump’s presidency is yet to become available for critique (we are in the business of criticism, not of speculation, after all), but what we can, and must, take as our object is the confluence of social forces that brought him into office. Racism and sexism, yes. But those real forces are not in themselves sufficient to explain the tidal wave of political frustration that swept America this November. The 2016 election was a referendum on nearly 40 years of neoliberal politics, and it ended with a resounding declaration that the fatalistic stance Denny at once embraces and critiques — the future is already written, so shut up and smile about it — is not acceptable. This is the neoliberal politics with which contemporary art has largely aligned itself, and it has missed the mark. If artists and critics and curators want to be on the side of emancipatory politics, we’ve been playing for the wrong team.

“There is very special treatment for white upper middle class heterosexual men and their spouses and children, there is special treatment for fundamentalist Christians and fetuses.” So wrote the poet Eileen Myles in a humble typewritten letter from 1991, in which she objected to George H.W. Bush’s denunciation of “political correctness” and announced her own write-in candidacy alongside Bush, Bill Clinton, and Ross Perot. Myles mounted her pseudo-campaign at the height of the AIDS crisis and Jesse Helms’s culture war, but read it today and the déjà vu is unavoidable. The right is still railing against political correctness, in the forms of trigger warnings, safe spaces, and genderless pronouns, and liberals, for the most part, are still defending it tooth and nail. Despite the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and the triumph of marriage equality, despite Lean In and Black Lives Matter — despite, indeed, eight years under a black president — “white upper middle class heterosexual men” still come in first. And reproductive rights are still precarious, perhaps even more so in the coming years than in 1991.

It’s thus no surprise that Zoe Leonard’s I want a president..., a 1992 text written in response to Myles’s campaign, would become a sort of symbol during the 2016 election. Even more than Myles’s letter, Leonard’s text, which circulated widely on photocopies and posters in the early-90s New York art world, was a direct response to the AIDS epidemic and the government’s indifference to it. Now it reads as a nearly exhaustive list of every identity that doesn’t apply to Trump, or Hillary Clinton for that matter. “I want a president who lost their last lover to AIDS,” the text reads, “a president who has stood on line at the clinic, at the DMV, at the welfare office....” But hung at large scale alongside New York’s High Line — the poster is wheat-pasted on one of the struts of the Standard Hotel, whose website declares itself “thrilled” with the gesture — Leonard’s work is dislocated from its moment and the strange poiesis of Myles’s campaign. What might have been a component of a scathing takedown of the entire presidential institution slipped all too easily into a Hillary Clinton apologia. If we can’t have a dyke, a straight girl will do. If not a member of the working class, then better a Democrat than a Republican.

Courtesy Friends of the High Line. Photo: Timothy Schenck.

This is the trouble with subordinating political desires to subjective classifications: the boxes are just too easy to check. Is it really possible to believe, after seeing the persistence of racial inequality under our first black president, that the identity of one can become a politics for all? That’s not to say that the “white upper middle class heterosexual men” Myles castigates don’t continue to receive “special treatment”; they do, and they should not. It is to say that after 25 whole years of Myles’s and Leonard’s strategy, the results have been rather disappointing. Works of art, if nothing else, play a vital role in how we conceptualize society. And if works of art continue to regurgitate failing political models, what is there to do?

Arts discourse has been guilty time and again of mistaking the old for the new, congratulating itself for innovation when in fact it’s just rehearsing the same tired scenes. This year it made the opposite mistake: it mistook something new — the emergence of Trump as a serious presidential candidate — for something old. (And it couldn’t even agree on what that something old was! The culture wars of the 80s and 90s? The rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s? References were even made to the fall of the Roman Empire!) In cases like Leonard’s, it responded to what it thought were old problems with old solutions: relics of the culture wars, the civil rights era, 1960s artist activism, even the protests of 20th-century suffragettes. When our social reality called for radicalism and foresight, we turned instead to the archives.

“Blockchain Future States” looked forward into what was actually a false mirror, and I want a president... looked back. The first cynically reproduced a defunct near future, the second reproduced a failed past. Neither of these two poles of political art rose to the challenge posed by the increasingly unstable present. The organizers of the exhibition “Decolonize This Place” at Artists Space seem to have made an attempt to avoid these twin pitfalls by taking another tack altogether: forgoing art objects and handing the reins instead to a smattering of activist organizations. There was something eerie about the main gallery. It was draped in protest banners for a cacophony of causes: “Justice for Akai Gurley,” “NYC Not for Sale,” “Respect the Ancestors,” “Mourning for all those massacred in Gaza.” I suppose it was a well-intentioned effort to strengthen these worthy causes by uniting them, but this display only undermined its components. It read like a museum of movements, banners hung like artifacts inscribed in a long-lost language.

A flyer informed that these banners would in fact be transported from the space throughout the duration of the engagement for various “actions” across the city. More like an activist armory, perhaps. What was available to the eye in the space itself was secondary to what “Decolonize This Place” was: a platform, a studio, a printing press, a classroom, a town hall, a concert venue. It stood for indigenous struggle, black liberation, a free Palestine, global wage workers, and de-gentrification. It was vigorously anonymous. The organizers were identified only by the name of the exhibition, which they credit to actions taken against the Brooklyn Museum in May 2016; a number of artists charged that exhibitions of Israeli photography and of political murals “utilized arts and artists to normalize the ongoing displacement of populations.”

Archive or armory, more than anything this represents art giving up on itself. “Decolonize This Place” deemed the production, display, and discussion of works of art insufficient, and it handed over the gallery’s resources to something deemed more apt to address the present. The tragedy is, that something is even more politically impotent. Sprawling lists of injustices and sites of struggle barely cohered, and the sheer volume of the project’s undertaking distracted from its few stronger components. There was, for example, a pamphlet that took clear and thoughtful aim at the American Museum of Natural History, whose mannequins of Africans and indigenous Americans are displayed in much the same way as taxidermy animals. Here, the organizers levied a focused claim against a powerful symbol. Less successful was a Friday night concert in support of protests against the construction of a pipeline through Native American land in North Dakota (a $20 suggested donation went toward the cause). While it was refreshing that the political concert featured more than one-note protest songs (there was an enjoyable set by Laura Ortman utilizing violin, voice, and synthesizers), the event tumbled quickly into a self-congratulatory dance party. The audience raised their hands to the ancestors and engaged in an energetic call and response: “No pipeline!” “On indigenous land!” Events like this do little to further the cause of art or politics, and while we all need a rest from the struggle from time to time, I know plenty of bars with less pretense and no cover charge.

The most striking claim in the exhibition’s programmatic flyer is disguised as its most self-evident:

At a time when so many people in this city are fighting to stay in their homes, or going into debt just to make rent, arts institutions, with sizable resources and infrastructures, have an obligation (and an opportunity) to avoid being part of the urban problem and to become part of the solutions emerging from the grassroots.

An obligation? Hardly. It should not be surprising that at a time when government at all levels fails to respond to the real needs of its citizens, artists turn to arts institutions to take its place, rehearsing over and over again the artist-as-activist model of the 1960s and 1970s. But we should not fall into the trap of believing that these institutions have anything like the civic obligations of, say, a housing commission, or the democratic mandate of a city council.

There’s an old tenet of aesthetics that got lost somewhere between the 60s and the turn of the millennium, between Robert Morris’s Notes on Sculpture and Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics. The nail in its coffin, I think, was driven in by the postmodernist tendencies that rejected the so-called grand narratives of modernity, and which flooded universities and art magazines in the later 20th century with approaches to art making unmoored from dusty domains of beauty and taste. It is the idea that art is useless. It does nothing; it serves no purpose. And yet from this uselessness springs endless possibility. Unlike everything else in the world, every other commodity and institution, every political campaign and government program, we are given the opportunity to confront and contemplate works of art freely and at play. “In a judgment of taste,” Kant wrote in the foundational text on the matter, “the imagination must be considered in its freedom.” What can be more political than an untethered imagination, a fleeting, momentary exercise of freedom? Art can achieve this radical potential — can have true political force — only when it stops trying to be something else, when it embraces its very lack of obligation and its abundance of opportunity.