The Offending Article

by Andrew Maerkle

Seventy years ago Japan surrendered. The legacy of empire and militarism has reemerged at a museum on the Izu Peninsula, and in the prime minister’s office

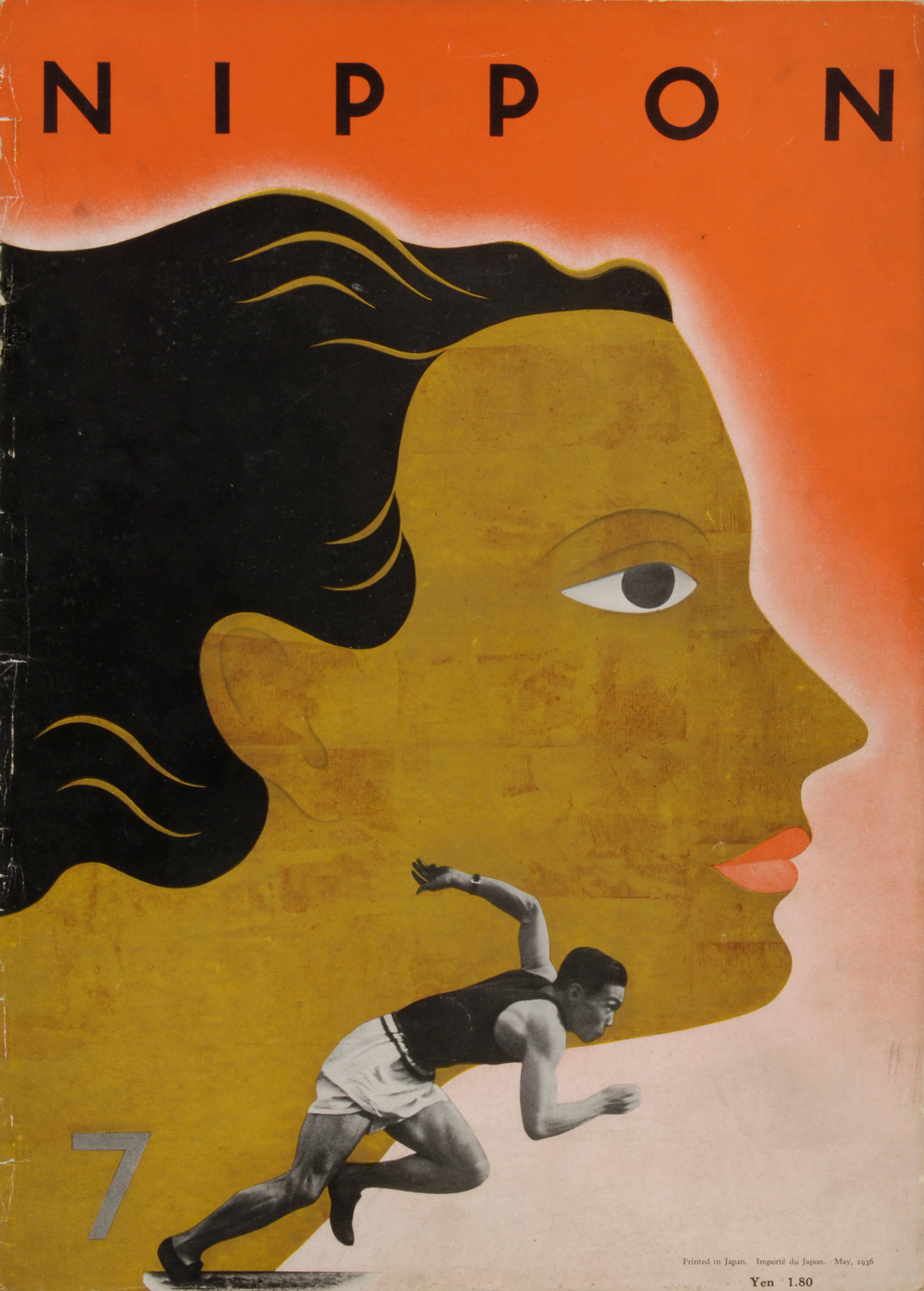

Issue 7 of Nippon magazine. 1936. Cover design: Takashi Kono. Cover photograph: Yonosuke Natori. From the exhibition “War and Postwar,” Izu Photo Museum.

This essay appeared in Even no. 2, published in fall 2015.

Following the earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima nuclear catastrophe of March 11, 2011, a popular movement arose in opposition to the continued use of nuclear energy in Japan, with massive protests in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park and in front of the National Diet. When the then-ruling Democratic Party of Japan proposed a 30-year timeline for phasing out nuclear power, it was a victory for participatory politics. But everything was reversed by the general election of late 2012, which the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party carried in a landslide. Nuclear energy would be necessary to fuel growth, the new government insisted — the first instance of prime minister Shinzo Abe’s use of cabinet fiat to overrule public sentiment. Last December, in an echo of wartime practices, a state secrets law came into force that provides prison sentences for government officials who leak information to the press, as well as for reporters. And then, this September, the Abe government won its battle to “reinterpret” Article 9: the provision of the postwar constitution in which Japan explicitly renounces war. Once again there were protests and petitions, but Abe got his way.

Repeating the authoritarian turn that precipitated World War II, the current crisis of Japanese democracy has also raised the stakes for art here. Has art, as an institution, in any way facilitated the current situation? Have artists and art professionals been too complacent in conforming to infrastructural and market pressures — from museum bureaucracy to high rents — that discourage the production and dissemination of challenging works? How should artists respond? Is there anything art can do, when even protests and petitions are ineffective? And what lessons does Japanese art of the war years have for artists in a newly militant contemporary Japan?

The current discourse of postwar Japanese art and culture tends to treat the end of the war as a tabula rasa, with only vague references to the censorship, propaganda and ideological control of the years before 1945. We should be thankful, then, for “War and Postwar: The Prism of the Times,” an exhibition at the private Izu Photo Museum south of Tokyo. This painstaking, important show, mounted in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, marshals an almost overwhelming array of archival materials to map the continuities in the use of photography before, during, and after World War II. The curators, Masashi Kohara and Mari Shirayama, have mustered not only original and modern prints but also magazines, publications, posters, scrapbooks, contact sheets, and paste-ups. The result is a timely indictment of the assumed neutrality of the photographer/artist — or, more specifically, of the stock photograph, which can be transferred from negative to print to page to billboard, cropped, enlarged, montaged, archived, licensed, and constantly reproduced and recontextualized, ever pliant to the demands of whatever ideology happens to control it.

Organized chronologically, the exhibition begins with the work of Yonosuke Natori and his Nippon Kobo agency, which in 1934 launched the multilingual pictorial journal Nippon to promote Japan and Japanese culture abroad. Described in a 1937 Life article as a “handsome, cheerful, easy-mannered young aristocrat whom nobody could help liking,” Natori started his career in Germany before returning to Japan in 1933. He quickly identified other promising photographers and designers, like Ihei Kimura and Hiromu Hara, to work alongside him. It was primarily this cadre, collaborating with newly established governmental and quasi-governmental organizations like the Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai (The Society for International Cultural Relations, precursor to today’s Japan Foundation), who would shape the visual representation of Japan for both foreign and domestic eyes in the years to come.

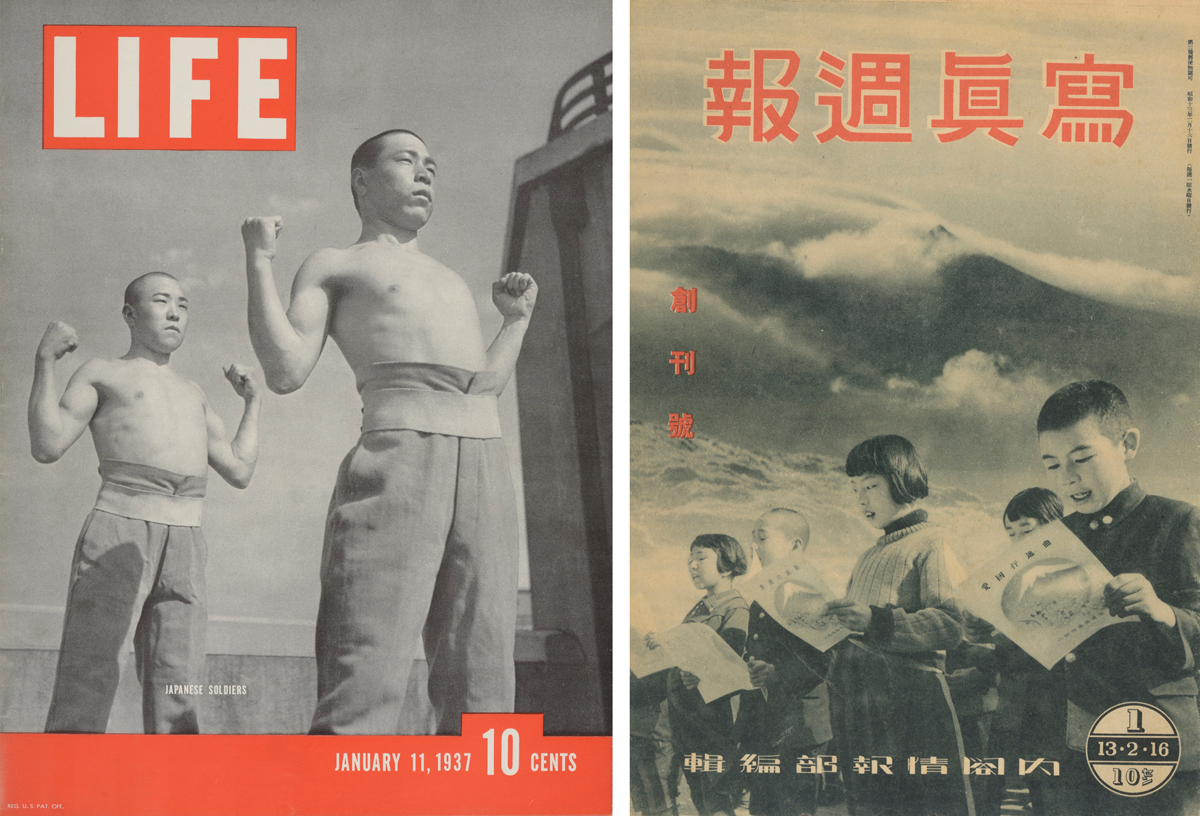

Right: Issue 1 of Shashin Shuho, February 16, 1938. Cabinet Information Bureau. Cover photograph: Ihei Kimura.

From the exhibition “War and Postwar,” Izu Photo Museum.

Together, they established a complex aesthetic combining a self-orientalizing gaze with a phallic, machinist sensibility, intended to communicate both Japan’s (alleged) unique otherness and its technological sophistication. The cover of the inaugural issue of Nippon, for example, features a stylized figure of a young woman in a red kimono, evoking a kokeshi doll, superimposed against a black-and-white photo of a multi-story concrete building. Similarly, an image from the KBS-produced photobook Sports (1939) shows a man doing the breaststroke in a pool. The photo is shot from above, and, as though the lens has been warped by the swimmer’s sheer muscular energy, the water swells in ripples of refracted light around his body, naked save for a hemp thong. The traditional swimsuit contrasts with the grid of the pool’s tiles below, emphatically placing this scene in a modern context.

As Japan's foreign relations deteriorated, the agenda turned to consolidating hegemony over other Asian nations, instilling Japanese values in occupied peoples, and boosting confidence in the colonial enterprise among the Japanese populace. Pictorial journals were rolled out for different territories, with titles like Shanghai (1938–39), Canton (1939), South China Graphic (1939– 40) and Manchoukuo (1940), each following Nippon’s lead in pairing boldly colored design elements with striking black-and-white photographs. Even as the war turned desperate, production continued on Front (1942–44), printed on stock so heavy it could no longer be air-freighted, as well as the domestically oriented Shashin Shuho (Pictorial Weekly, 1938–45), which had to change format as first the metal for staples, and then paper itself, grew increasingly scarce.

The end of the war barely interrupted the activities of these photographers and publishers, who set out to work with the same stock imagery they had been using before, but now with the intent of promoting peace and American-style democracy. By 1946 the publishers of Front already had their first postwar title out: Pictorial Alphabet, a smartly designed language primer matching generic images (a castle, say) with their corresponding words in English and Japanese. Meanwhile, a team of photographers from Sun News Photos, successor to the prewar G.T. Sun agency, were invited in December 1945 to photograph the newly human emperor, Hirohito, relaxing at home with his family, examining his zoological specimens, and reading the US military’s Stars & Stripes newspaper.

Among those who shot the Hirohito portfolio was Yosuke Yamahata, who as a military photographer had been sent to document the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. He captured agonizing scenes of the devastated landscape, strewn with rubble and charred bodies, and of the dazed survivors. But even though Japan would surrender in six days, Yamahata was under orders to find images that could be used for military propaganda. He staged a number of the photos, including one of a young woman emerging from an underground bomb shelter. Accentuated by her headscarf and some stray locks spilling across her wide brow, she appears to have dropped in from a weekend excursion, and the beatific smile playing across her face, so incongruous with her surroundings, testifies to the powerful reflexes conditioned by the erotics of camera and subject.

None of the photographers in “War and Postwar” were prosecuted for collaborating with the wartime regime. Instead, their names now grace some of Japan’s most prestigious photography and design prizes. From their point of view, they were simply pursuing a vocation. But at what point does any individual have the obligation to say no, to refuse to participate? Since returning to Japan in 2007 after studying in London at Chelsea College of Art and in Amsterdam, at the Rijksakademie, Meiro Koizumi has made a series of multimedia works focusing on one of the most sensational aspects of the war: the pilots of the kamikaze special attack units. As his recent solo show at the Arts Maebashi art center in Gunma Prefecture confirmed, his head-on engagement with the legacy of the wartime era places him at some distance from the Japanese contemporary art mainstream. The multi-channel projection Portrait of a Young Samurai (2009), for example, shows four different views of a young actor dressed in pilot gear, performing a farewell message from a kamikaze pilot to his parents. With each take, an off-screen voice — Koizumi’s — exhorts the actor to express more “samurai spirit.” The voice pushes him again, and again, until finally there is an explosion of raw emotion, with Koizumi spontaneously participating in the role of a hysterical mother.

Another video work, Defect in Vision (2011), features a couple — an airman and his wife — eating a meal at home, discussing the progress of the war and their plans to take a trip to a hot spring once it’s all over. As they fumble with their chopsticks and stare into space, it becomes apparent that the actors are both blind. The video ends with the husband calling out his wife’s name as he hurtles to his death; this last scene appears to have been shot on a roller coaster, and the airman’s cap and goggles used as props flutter ridiculously on the blind actor’s head.

Koizumi’s art has consistently investigated the complex dynamics between the real and the constructed, and the artist has stated that these works are meant to subvert latter-day jingoistic films about the war. The camp overtones of Portrait and Defect certainly reinforce this position — and yet, in another sense, the cruelty and cynicism of Koizumi’s videos have the opposite effect of arousing sympathy for the soldiers they depict. Achieved through means of borderline sadistic control, the steroidal spectacle of emotion realized by the actor in Portrait and the sentimental irony of the objectified blind couple in Defect come pretty close to absolving these figures of their individual agency. Although they outwardly borrow the framework of didactic theater, the works are symptomatic of an ongoing contemporary confusion about responsibility for the war, which ultimately lies with the Japanese people as a whole.

Perhaps the institutions of contemporary art here, caught between the market and the state, simply don’t have the capacity for a full reckoning with the legacy of the war, let alone with Japan’s current bellicose turn. I wondered as much when I saw Fires on the Plain, the latest film by Shinya Tsukamoto, best known for his cyberpunk-horror classic Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989). In interviews, Tsukamoto says that he spent years planning an adaptation of Shohei Ooka’s eponymous 1951 novel, which recounts the physical and spiritual unraveling of a Japanese soldier fighting in the Philippines, but producers didn’t want to touch the anti-war content. Then, as the Abe government began its push to rewrite Article 9 — and with the number of veterans of World War II, who have been some of the most prominent opponents of re-militarization, continuing to dwindle — Tsukamoto felt an urgency to act.

The story of filmmakers scraping together shoestring budgets and calling in favors from old collaborators to realize their creative visions is familiar the world over, but it’s meaningful in Japan, at this moment, that someone of Tsukamoto’s stature would show that kind of commitment. He claims Fires is the most expensive film he has ever made. Working with lurid color video so detailed that it captures the hairs quivering in the actors’ nostrils, Tsukamoto has delivered a searing and thoroughly unglamorous depiction of the war experience, a hellish fever dream of gore and paranoia. Played by Tsukamoto himself, the protagonist, Tamura, stumbles numbly through the impassive tropical landscape, haunted by American GIs, by local guerrillas, and by the ghoulish figures of his compatriots, who exchange furtive rumors of acts of cannibalism among the disintegrating ranks. This is a zombie film told from the viewpoint of the zombies, if zombies could experience fear on top of single-minded hunger.

Tsukamoto goes to great lengths to ensure the realism of splattered viscera, but he also imbues the film with an overt theatricality that heightens its human terror. One of the major set pieces — a night ambush by unseen enemies — draws upon the characteristic spastic body movements of postwar Butoh dance. Soldiers stagger through a hail of bullets while attempting to hold their punctured innards. They reach out instinctively for dismembered arms, their squirming contortions quoting, and rebutting, wartime propaganda paintings glorifying violent death. Perhaps the method is a bit heavy-handed, a bit Clockwork Orange. But once all the veterans are dead, and the authority of first-hand experience can no longer be relied upon, imagination has to fill the breach. Although Tsukamoto says the film is open to interpretation, he makes it unambiguously clear that there is no humanism, no philosophy, no good on the battlefield. Its extreme violence is what pushes the film beyond the realm of platitude.

Everyone knows that Article 9 was not followed to the letter. Everyone knows the postwar constitution is a flawed document, foisted upon the Japanese by the American occupation. But Article 9 can also be seen as an affirmation, a promise to the future, and the fact that it has now been essentially scrapped is damning evidence that we have learned nothing from World War II. Some months after Meiro Koizumi’s exhibition at Arts Maebashi concluded, his work was back on view in a two-person show, with the experimental theater director Akira Takayama, at the Ginza Maison Hermès Le Forum in Tokyo. Koizumi was debuting a new multimedia installation, In the Land of Amnesia (2015). The artist asks a man with memory loss incurred from a traffic accident to memorize and recite a passage taken from the diary of a soldier — a former teacher, who was stationed with a top-secret chemical warfare unit in Manchuria, and who, under absolute orders from his superiors to leave no witnesses, murdered a child.

The work’s portrait of a man confronting his amnesia has taken on even more significance since Shinzo Abe’s August 14 statement on the 70th anniversary of the war, in which he argued, “We must not let our children, grandchildren and even further generations to come, who have nothing to do with that war, be predestined to apologize.” Abe and his cohorts, some of whom are indeed the children and grandchildren of the war’s architects, still mouth the words “Never again” each year at the Hiroshima peace memorial. But now they turn around to talk about how Japan cannot remain a “defeated nation” indefinitely, as if the past could just be erased. They might as well just say they wish Japan had won the war.