The Body Politic

by Madison Mainwaring

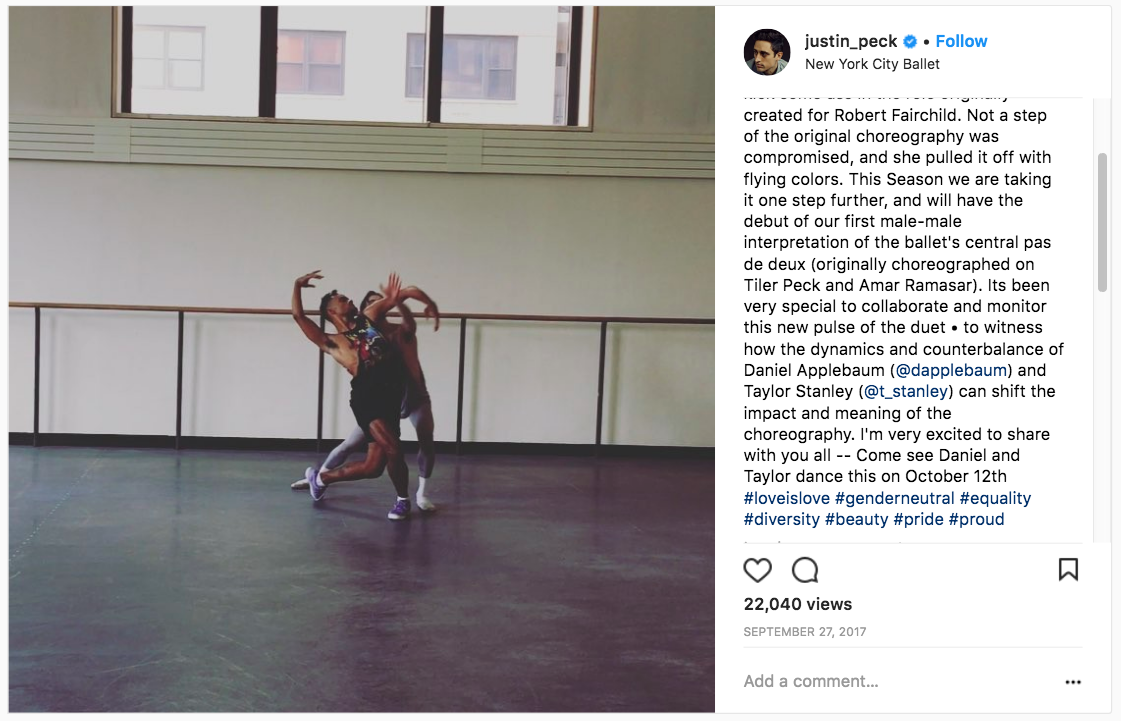

Taylor Stanley and Daniel Applebaum in The Times Are Racing. Choreography by Justin Peck. New York City Ballet. 2017. Photo: Paul Kolnik.

When a man extends his arm to support the back of his partner, then carries his partner into the air while turning around, nothing out of the ordinary has taken place on the ballet stage. This counts as one of the tried-and-true moves in the pas de deux, the romantic duet representing the central repository of meaning in classical dance. Yet on October 12 of last year, when Daniel Applebaum performed this gesture on the stage of the New York City Ballet at Lincoln Center, he broke from tradition when he lifted Taylor Stanley into the air. Stanley is a man. In order to be partnered in such a way, he had taken over a role in The Times Are Racing originally created for a woman.

Broken down into its most rudimentary steps, ballet ignores gender: a plié is a plié no matter the kind of body executing it. When it was first recorded on paper with Beauchamp-Feuillet notation at the late 17th-century French court, the symbolic language of movement was the same whether the dancer was identified as male or female. In the 18th century, the strict geometries of its technique were aligned with the Enlightenment project of universalizing the human figure and neutralizing anatomical differences.

Only in the wake of the French Revolution did ballet come to be profoundly sexed. This binary is epitomized in the hard-edged pointe shoes worn by the ballerina, elevating her to new heights while inscribing her body with what came to be a culturally entrenched brand of femininity. Go to the ballet today and you will notice that men jump higher and turn faster, whereas women work from more exacting, delicate positions of the arms and upper body. When a man and a woman dance together, he partners while she is partnered — a grammatical skew reflecting the strict binary roles of the art form. When I asked Stanley about this, he said that The Times Are Racing’s pas de deux was a completely different physical experience for this reason. “You suddenly have to evaluate the concept of your own weight and give in to your partner,” he told me, “separating from that fixed mentality of being in charge.”

The theatricality of ballet has always highlighted gender as performance, though when men have assumed female sensibilities and style, it has usually been as a joke. Drag is de rigueur in comedic roles, such as the nurse in Romeo and Juliet, or Bottom in Frederick Ashton’s The Dream (1964), who sprouts hooves out of black pointe shoes. When gender norms are troubled onstage, they often seem to suggest that there is no trouble at all. Choreographers who wanted to make a serious critique of what the critic Ann Daley called “patriarchal ceremony” often leave ballet altogether for modern or contemporary dance, as if the technique itself were in the wrong.

Then again, perhaps it is. The virtuosity required of classical dance makes it a decidedly institution-bound art — one must learn from the masters — slow to reflect societal changes beyond the proscenium arch. A number of notable male choreographers of the last generation were outspoken about their gay identities, but this did little to influence their casting decisions, as they almost invariably took up male-female partnering as one of the working constraints of the art form. And not everyone has a problem with that: the New York Times critic Alastair Macaulay, for one, has argued that ballet can transcend gender because the spectator identifies simultaneously with the man and the woman. “When I watch Swan Lake,” he wrote in 2013, “I follow both heroine and hero as if they were aspects of myself.”

Justin Peck, the 30-year-old creator of The Times Are Racing and resident choreographer at New York City Ballet, is of a different opinion. He announced that Stanley would take over the traditionally female pas de deux role on Instagram with the hashtags “#loveislove #genderneutral #equality #diversity #beauty #pride #proud.” For a March performance of The Times Are Racing, he cast the ballerina Ashly Isaacs in a role originally created for Robert Fairchild, another gender-neutral first; during that performance, Stanley danced as her non-romantic partner, enacting the same movements by her side. Interchangeability as a negation of difference appears to be one of Peck’s calling cards. (He watches videos of flocks of birds for inspiration, in order to escape the expectations within the human-to-human pecking order.) The Times Are Racing was made in a spirit of protest, the dancers donning costumes by Opening Ceremony with labels such as “Defy,” “Unite,” and “Act.” The organization of the corps de ballet — dancers of the lowest rank, expected to repeat the same gesture collectively — has long reflected cultural assumptions about the body politic. In this case, they were self-avowedly woke.

The Stanley-Applebaum duet offered a rare flash of emotional perception in which the dancers — both gay — could explore their physicality in unprecedented ways while also revealing something of their personal truths. Peck draws upon the dancers’ energies and rhythms outside of the studio walls and redirects them into the vessel of high art. They believe in his work, and it shows. Yet this success was undermined by the apparent necessity to hedge the ballet’s reception with various labels — on social media, and with costumes — as if classical dance couldn’t be trusted to speak through its own formal terms. Ballet transforms the body, the vulnerable site of physical reckoning, pleasure, and pain, into an amazingly expressive instrument. It could be used to explore, rather than reinforce, preconceived notions of gender, and its lack of language could prod us to pay attention to bodies as they are, rather than as we think they should be. If ballet can show us that “love is love,” it would not be via a hashtag, but by its audience peering through the dark toward the light of the stage, witnessing dancers coming together in new ways.