Stand Clear

by Michael Kinnucan

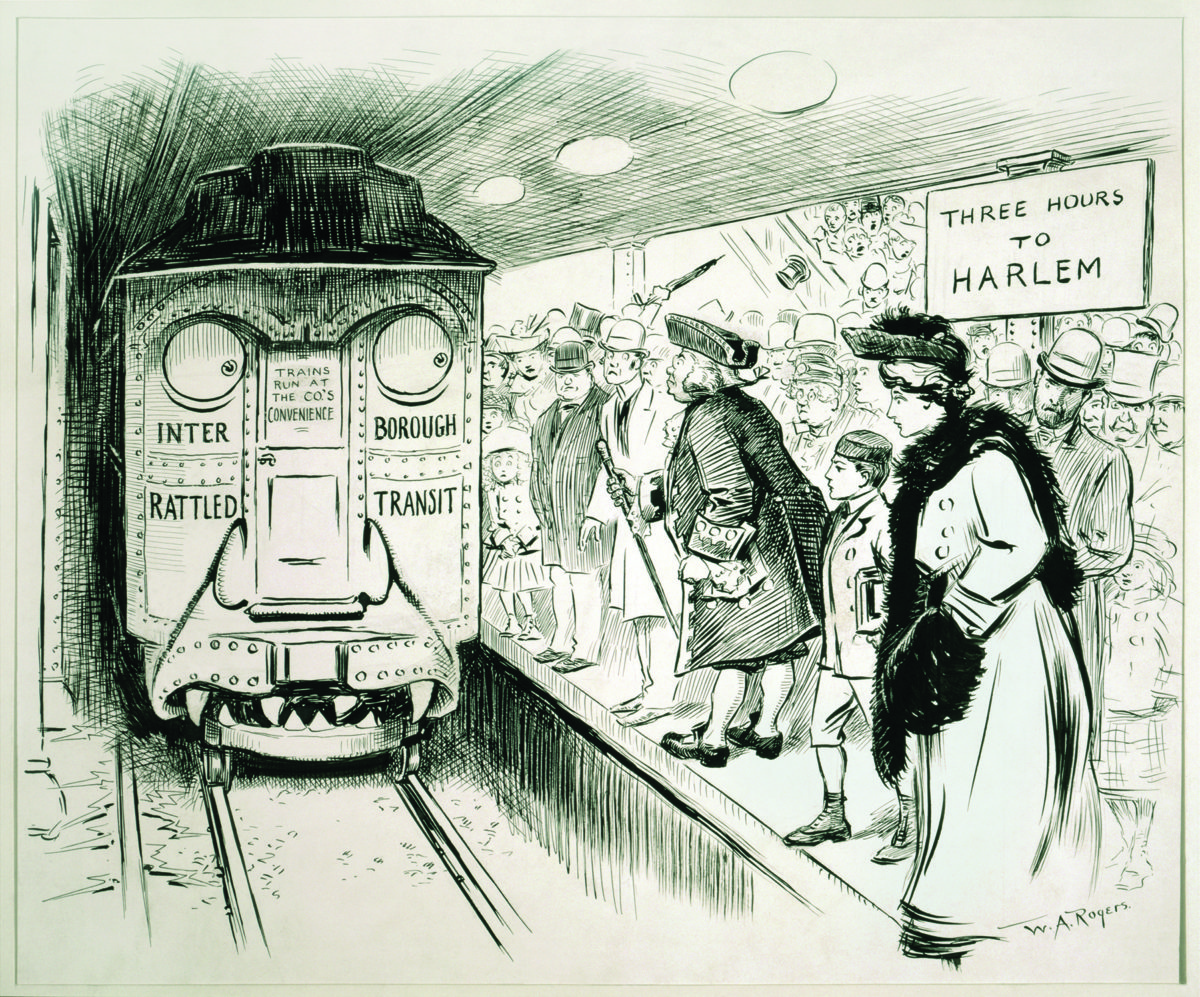

"Three hours to Harlem”: A political cartoon from the New York Herald. 1905.

New York City’s subways are falling apart. Not a day goes by without delays and breakdowns—cars full of passengers have derailed, and more than once this summer commuters have risked death (and malicious rats) to escape stalled trains by foot. The L train, which I take from Brooklyn to Manhattan every day, is so packed at rush hour that lines on the jammed platforms run up the stairs. Some days, three trains will go by — too packed to board — before I can get on; I’ve missed work because of this, and friends who weren’t as lucky have lost jobs. If it’s not painfully obvious why this nightmare exists, the subway system is operating at twice its intended capacity, at nearly 1.76 billion annual rides. A forward-thinking government might have addressed the calamity before it began, but warnings a decade ago went unheeded, and now a rising tide of riders is overwhelming the fragile subway system; merely maintaining its current hellish level of operation would cost billions and take decades. (The trains still employ ancient signaling technology, and will take at least 50 years to upgrade.)

Anyone looking from the Brooklyn side of the East River can see the irony of New York’s skyline: the soaring skyscrapers that represent the heart of capitalism are untenable without the vast subterranean network of public infrastructure that fills those towers with workers every day. Now that network is decaying; the new World Trade Center station, whose Calatravesty cost the city $4 billion, didn’t even increase rider capacity. This is the great paradox of New York in 2017: even as the city booms, the city is collapsing. How could a city that once built 842 miles of track in two decades, the largest in North America, now barely keep its core transport system from falling apart?

The state’s leaders — above all the governor, Andrew Cuomo, regularly cursed by today’s straphangers — deserve a healthy share of the blame, but the political origins of this crisis go back decades, and reflect New York’s dual heritage as the home of global capitalism and the cradle of American socialism. What we today call the subway is a fusion of two private systems, the Interborough Rapid Transit and the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit, which went bankrupt in 1940 and were taken over by the city government, then led by the mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. At the time, New York was also the paragon of the nation’s experiment with social democracy; the city’s workers’ movement was unparalleled in its radicalism and power, and improvements to the subway accompanied massive growth in public housing, tenant protections, and new public hospitals and universities.

But the back of worker power broke during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s. New York came within days of bankruptcy, and creditors gained control of the city’s budget, as they have of Greece’s and Puerto Rico’s today. The graffiti-covered subway in the 70s became a byword for New York’s decline; ridership dropped to record lows. It was on those ashes that the mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg began to build the privatized amusement park that now has the lowest crime rate of any major American city, and the highest median rent of any besides San Francisco. Public housing is in disrepair, tenant protections are eroded each year, tuition at CUNY is soaring even more quickly than Lincoln Tunnel tolls — and the subway, the city’s most important public utility, has been left to crumble in favor of quixotic vanity projects like a light rail line that runs through sparsely populated bits of Brooklyn and Queens, or a new train to LaGuardia Airport that will be slower than the bus.

Andrew Cuomo, who declared a state of emergency for the subway this summer, is a post-ideological Democrat in the Clinton mold who boasts of on-time budgets, low property taxes, small government, and “common sense.” It’s a delicious irony that this hard-nosed realist whose only ambition is to make the trains run on time has presided over a massive failure to do even that — or it would be a delicious irony, if I didn’t happen to commute here. It’s unthinkable that the diversity, immensity, and vastness that is New York City is governed by such purblind, small-minded men. Yet Cuomo’s politics mirrors in many ways New York’s left: hammering at minutiae for decades, it seems to have lost the capacity to imagine and respond at a scale adequate to the city’s needs. Young activists these days fight to defend working-class neighborhoods from gentrification, but have trouble creating and enacting solutions to the city’s housing shortage; they fight to keep subway fares low, but can’t fathom to address the transit system’s daily operational needs. There are good reasons for this: the money isn’t there, nor is the political power. But we need to find a way, because those sad defensive battles we’re fighting won’t even preserve what we have.