A Society of Gentlemen

by Huw Lemmey

In 1967, Britain legislated that sex between men was no longer a crime. Fifty years on, London’s museums are gayer than springtime — but the stories they recount are missing some pieces

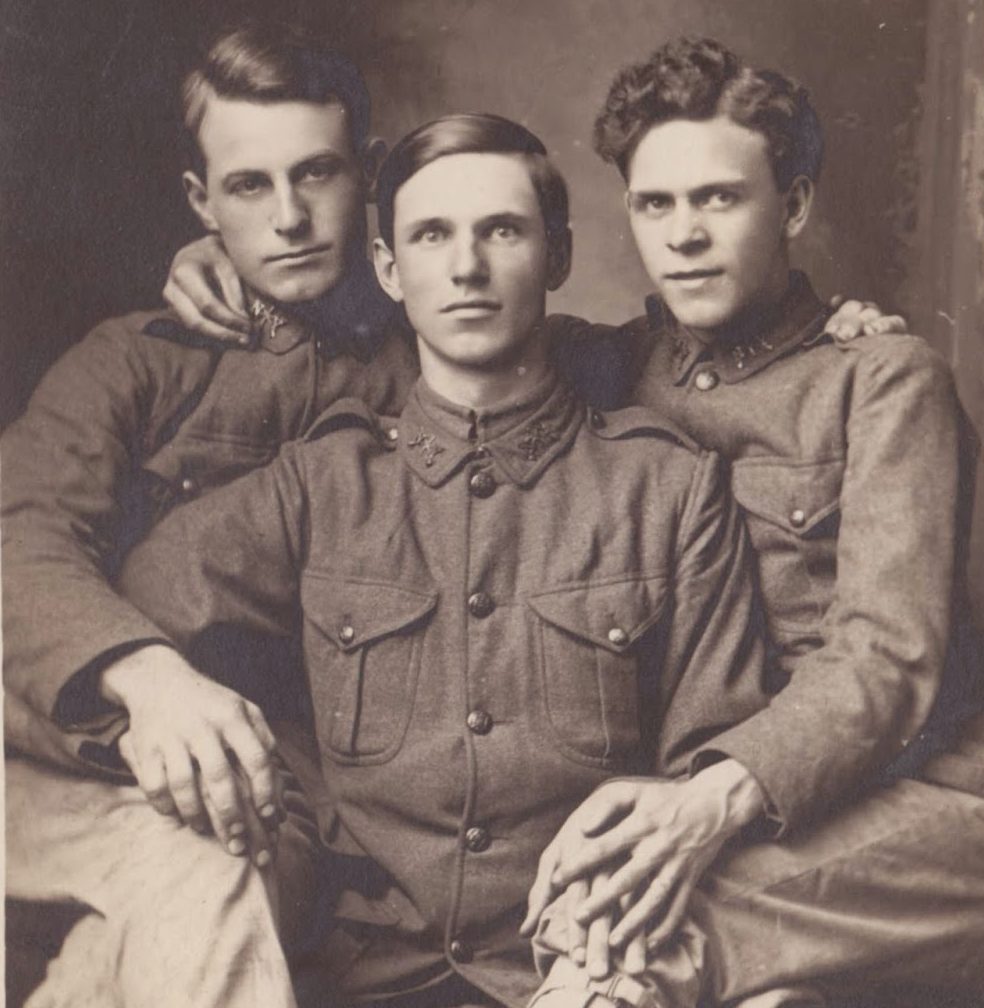

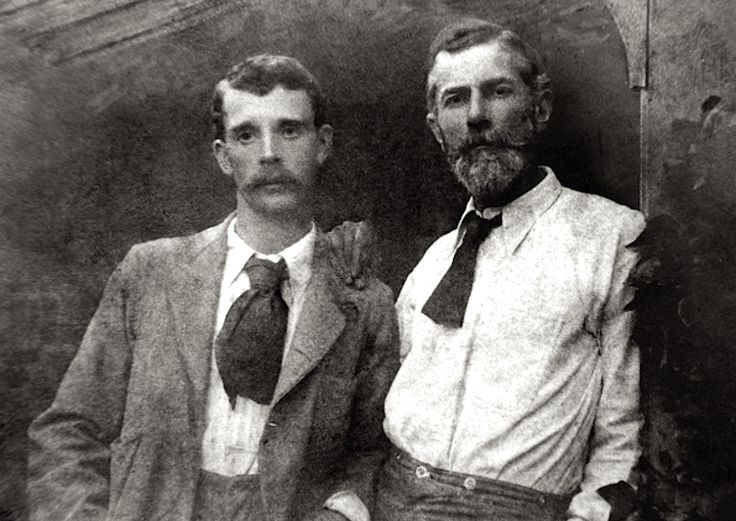

It was a single physical gesture, a touch that was both fraternal and sensual, that supposedly inspired E.M. Forster’s long-suppressed paean to homosexual love, Maurice. “George Merrill also touched my backside — gently and just above the buttocks. I believe he touched most people’s,” he wrote decades later, having never forgotten the fingers that stroked him in 1913. Forster had never had sex before, but the touch of Merrill, the young, working-class lover of the older socialist poet Edward Carpenter, electrified his Edwardian frame. Forster would go on to claim that his novella, the tale of a Cambridge graduate who finds lasting love with a gruff gardener, had been generated instantly, in its entirety, when that hand caressed the small of his back.

A couple of years later, while working for the Red Cross in Egypt during the Great War, Forster began his first love affairs with men. But Maurice remained in a desk drawer, and was published only in 1971, after his death. Prior publication would have been more than just professional suicide for an author of his esteem: he might also have faced prosecution, incarceration, and torture at the hands of the British state. In the end, it was only due to the persuasive abilities of Forster’s young friend, the author Christopher Isherwood, that Maurice was published at all.

In the mid-19th century, when Carpenter was a young man, buggery could see you hanged. In Oscar Wilde’s time it could get you years of hard labor. Consensual sex between men only became legal in England and Wales in 1967, when Parliament begrudgingly passed the Sexual Offences Act, acting on legal principle but with open moral disgust. The Act, for all the foot-dragging that preceded it, catalyzed a huge change in the moral and intellectual culture of English society, and 50 years later, gay freedoms are being celebrated with unprecedented programming by the BBC, the British Film Institute, the royal palaces, the National Trust, and almost all of London’s major museums. (I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that, even ten years ago, the idea of celebrating the Sexual Offences Act would have still been a minoritarian endeavor.)

What’s emerged from their attempts to produce compelling and coherent historical narratives, however, is an understanding that the legal and cultural suppression of public homosexuality has left us with only meager remnants of England’s gay past. And amid those remnants, England’s intellectual elite continues to dominate, their lives bound up with Britain’s imperial history as well as its surviving reactionary powers. Meanwhile the queer, the rough, the half-hidden and the proletarian traditions have largely passed into obscurity, due not least to the lacuna in our oral history that was a side effect of the devastation of AIDS.

The treasure room of the empire’s loot, the British Museum, has relegated its show “Desire, Love, Identity” to a tiny room in the coins department: a dimly lit metal vault, the same shape and dimensions as a Victorian public toilet. This summer, as I peered into the case containing fascinus amulets — those wingèd penis charms depicting the Roman divine phallus — I became aware of the presence of an older man who stood behind me, leaning in a little too close. I tried to shift my body sideways, without catching his eye, without brushing my arm against his summer-damp tweed suit. Occasionally a tourist entered, assuming this little gallery housed just another temporary exhibition; as the handful of activist badges caught their eye, proclaiming in pink that “Silence = Death,” or that someone, once, was “Glad to be Gay,” they slinked out, sorry to have disturbed our quiet little room.

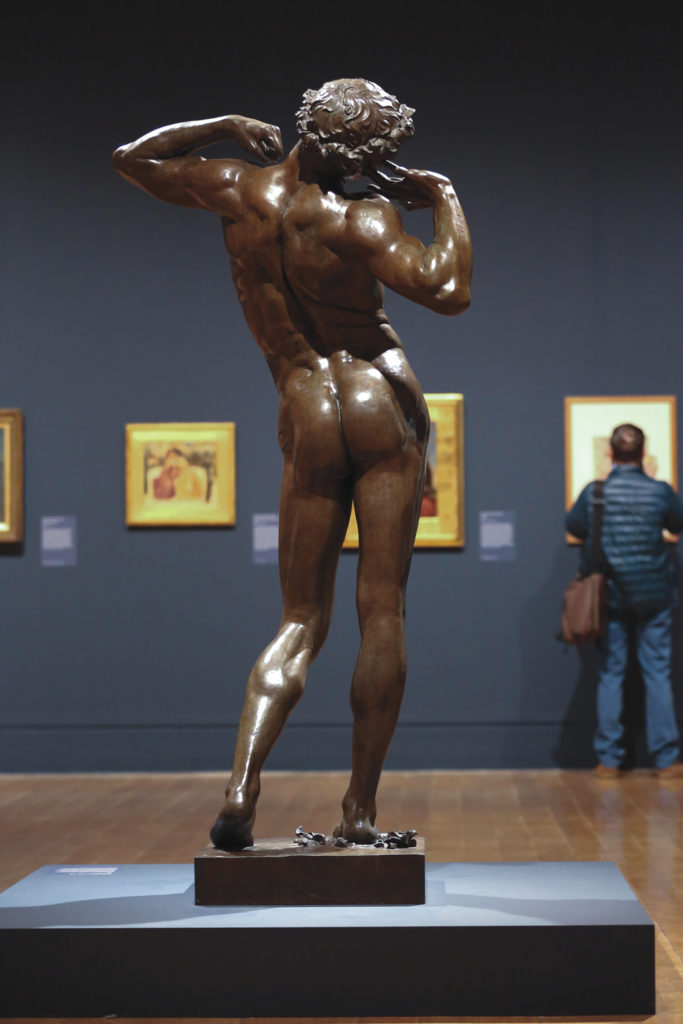

A flyer by the door listed the location of works in the permanent collection that might otherwise have found a place in the little room; a medieval etching of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, the patron saint of homosexuals, archers, and plague victims, or the twin busts of the Emperor Hadrian and his boy lover, the (literally) divine Antinous. Also listed on the tour is the famous Warren Cup, a 1st-century-AD silver drinking vessel depicting two scenes of pederastic sex. The cup was offered to the British Museum in the 1950s but quietly rejected, the directors fearing the purchase would never meet the approval of the museum trustees, among them the Archbishop of Canterbury himself. It wasn’t until the late 1990s that they finally got their hands on the pair of boys; in the intervening decades, the price had skyrocketed. Many of these items were once to be found in the Secretum, the museum’s secret collection of pornographic materials, kept firmly under lock and key after the passage of the 1857 Obscene Publications Act. The Secretum was eventually dissolved into the general collections in the 1960s; now, they hide in plain sight.

The museum sometimes feels like a Secretum in toto. Like libraries, museums somehow hold their own erotic charge. They’re public places, and free in England. They attract those with a free morning and nothing much to do. They attract students, too, and between these characteristics breed opportunities. The antiquities put your own society into perspective, and the toilets give you chances. It was in the British Museum that Maurice and Alec, the gardener, first met away from their rural homes. In Forster’s novella, Maurice arrives to parry a blackmail — “the police always back my sort against yours” — but in the end, they finally meet as lovers, as equals, referring to each other by their first names at last, before spending the night together. I dropped by the men’s lavatories at the rear entrance on my way out: the quiet toilets. They’re empty now.

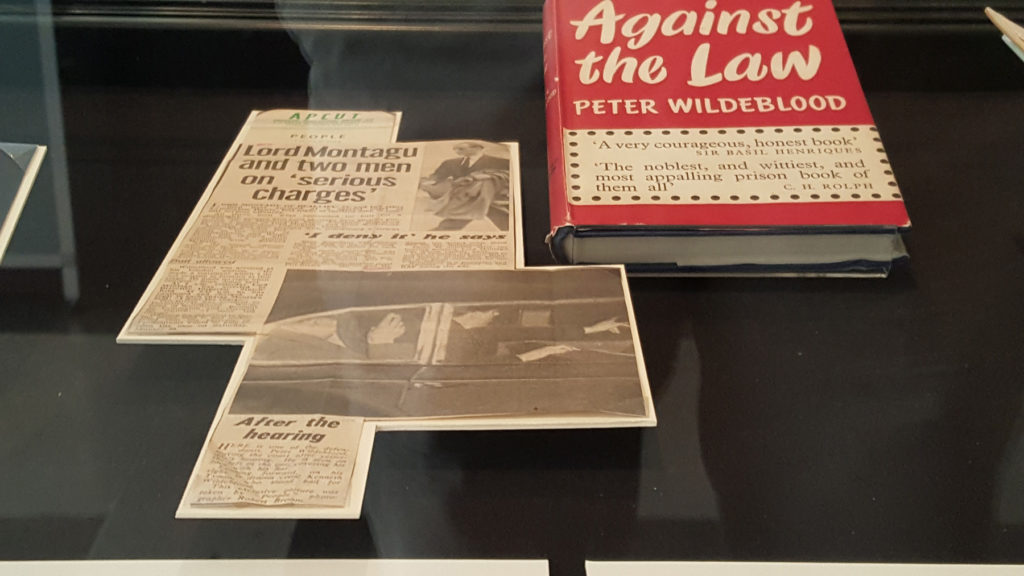

There are plenty of other spots to contemplate your queer self in relation to England’s homosexual history, though. Near the toilets in the foyer of the British Library — legendary conveniences for bored young scholars — was an exhibition documenting the legal reforms that have taken homosexuality from the dock to the mainstream over the past century or so. Unlike the BM show, “Love, Law, and Liberty” wasn’t drawn from the illicit historical artifacts of the Private Case (the BL’s own version of the Secretum). Instead it mapped, through diaries and posters as well as oral histories, the prehistory and consequences of the Sexual Offences Act. The trial of Oscar Wilde, for example, which remains the foundation myth of the gay martyr in Britain, was evoked through an early magazine serialization of The Picture of Dorian Gray, the contents of which were used to help convict him. Discriminatory legislation passed by the Thatcher government in the 1980s against the promotion of homosexuality in school surfaced here via a copy of Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, the children’s book that instigated a nationwide gay scare. And the show stretched as far as this decade, when the Cameron government brought in, with something less than unanimous support from his Tory party, the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act of 2013.

The Sexual Offences Act itself grew out of a parliamentary committee formed in the 1950s to examine homosexuality and prostitution, which was itself catalyzed by a scandal known as the Wildeblood Affair. In the summer of 1953, the young Lord Montagu allowed the use of a small beach hut on his estate for his cousin, Captain Michael Pitt-Rivers, and Peter Wildeblood to entertain two young airmen. They were arrested, charged with conspiracy to commit acts of gross indecency, and sentenced to a year to a year and a half in prison. The chairman of the committee, Lord Wolfenden (later director of the British Museum), delivered a report that suggested the law be amended to decriminalize homosexual activity, in private, between two men aged over 21. His report featured the voices of only three homosexual men. Two were Cambridge graduates. The third, Wildeblood himself, had attended Oxford.

The full report was on view at the British Library, behind glass, as was the Act of Parliament itself. But the aging paper didn’t tell the story; that was to be found in the myriad interviews with men and women affected by the legal arguments, and the ephemera of the years of struggle, before and after, when activists built cultural and social movements that forced England to loosen up a bit. The show was rich in its documentation of the grim tortures and persecutions visited upon us, but richer in the vivid magazines and newspapers of gay liberation, the manifestos lovingly kept, the LPs and the books. This integration of the legal story and the cultural was what gave the show its power; it felt as if the show didn’t emerge from the archives of the library, but from the living culture still maintained in the reading rooms. If you switched on Grindr here, you’d be unable to miss the fact that gay culture is a breathing, crying, sweaty thing, and the men and boys idly flicking their screens in the library, or arriving from the North at the nearby train stations, or trolling around the nearby parks: they, somehow, are the descendants of those people remembered in the show. In the rich, raw manuscripts and screenplays here — notably by working-class writers like Joe Orton and the “kitchen sink” playwright Shelagh Delaney — you can feel the heat of the firestorm of angry refusal and the public blossoming of culture and love that forced us onto the page as real people, across the classes.

That anger and love were missing from “Queer British Art,” at Tate Britain, where an attempt to tell the story of a queer identity before decriminalization managed to reproduce all the tendencies of English class anxieties that make this such a priggish, suffocating, small little country. Presented with an eye to a straight audience, it maintained that homosexual culture was important because it’s part of what it means to be English. “Surprise!” it says. “We were among you all along!” And it did so largely by presenting a history of gay subjectivity that barely wavered from the standard story of the ruling-class artistic movements that have long defined art in England.

The show opened with the late Victorian bohemian movements that gave the middle and upper classes a cultural space to challenge some of the political implications of a rapidly industrializing and urbanizing society. Advocating for homosexual freedoms, as Carpenter did, was just one part of a landscape of reform movements, such as the Arts and Crafts movement, which challenged the moral implications of the emerging mass-produced consumer commodity, or the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who reacted against the muscular and allegorical Victorian habits of the academy by painting pale, androgynous Greek heroes and Arthurian fairies.

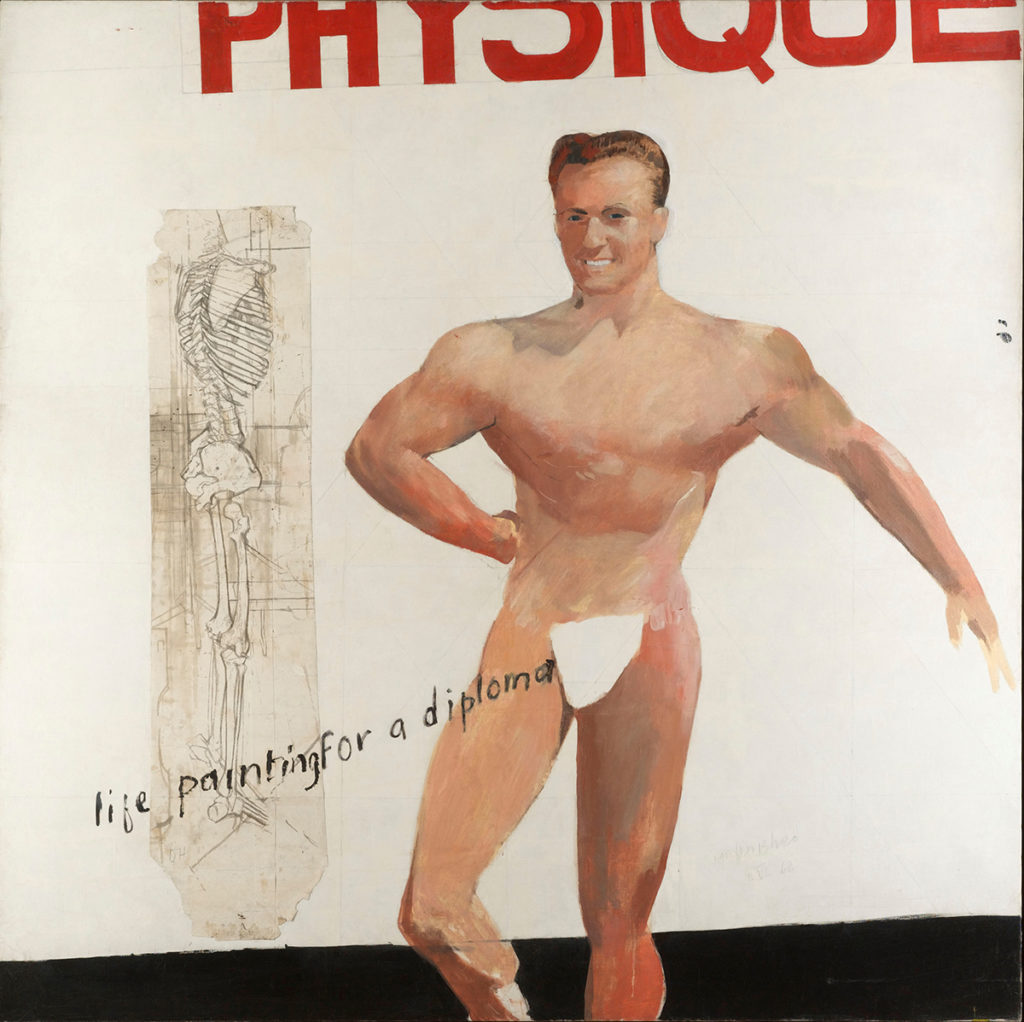

It’s this lineage that shaped “Queer British Art”’s idea of “queer” culture in the 20th century. The show prioritized movements such as the Bloomsbury Set, with whom Forster was strongly acquainted, although never really a member; the later bohemians of Soho in the 1950s and 60s, such as John Deakin and Francis Bacon; and ended just before decriminalization with David Hockney’s Life Painting for a Diploma (1962), a student work that pressed against the constraints of academic art education by using a men’s physique magazine as inspiration. Hockney’s non-elite background and subject stood out as a rarity in the show, and the crude and rough working-class gay man existed in “Queer British Art” only in portraits. Indeed, Forster appeared by proxy here in a painting of his working-class boyfriend, policeman Bob Buckingham, whose own life is referred to only in relation to the novelist.

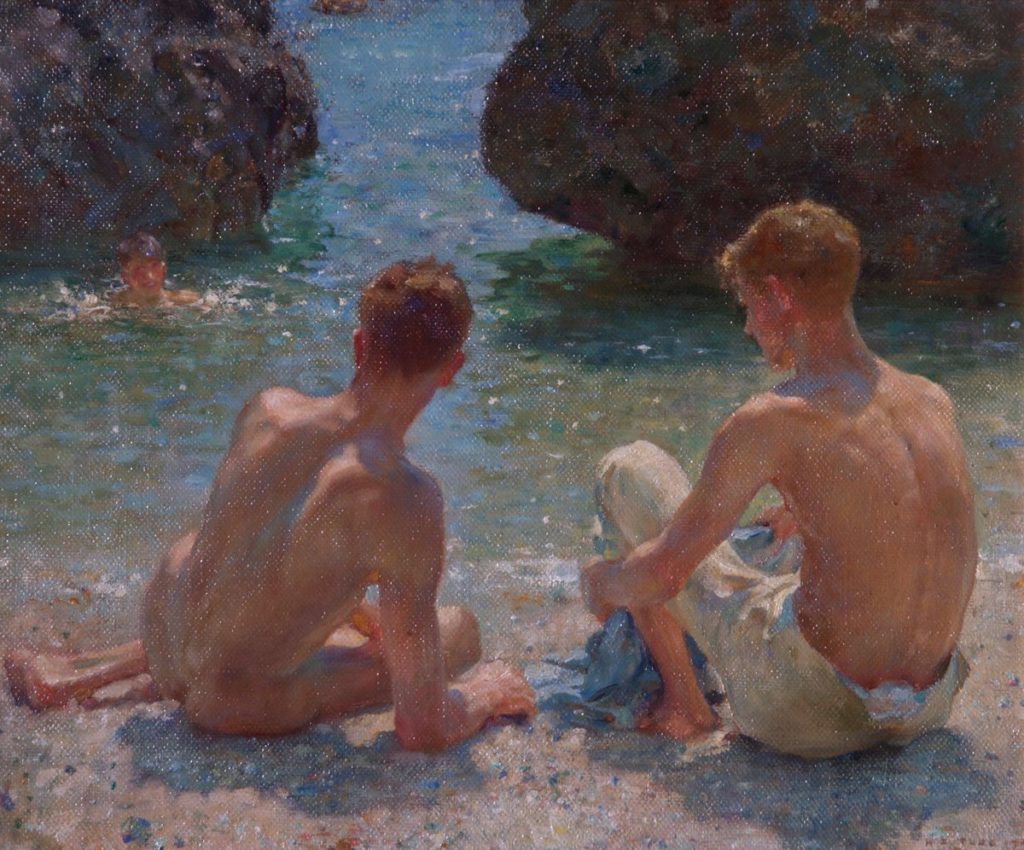

If the British Museum’s display of Pompeiian phalluses had a certain illicit allure, “Queer British Art” was as stifling as a suburban living room; each choice seemed a gesture towards some dead trope of a British gay identity that had no relevance to actual gay lives. Our legal oppression was marked by the inclusion of a full-length portrait of (Oxford’s own) Oscar Wilde, and his prison door from Reading Gaol. Keith Vaughan’s fast and violent secret sketches of boys marked our double lives, and endless waiflike boys and girls by water, our dreamy and aesthetic whimsy. Only the witty, mocking collages of Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, who defaced the covers of books stolen from the public libraries and later re-inserted into them, providing the lads with endless mirth and an eventual jail sentence, carried any of the anarchic and erotic energy that might represent your own desire to actually fuck someone. I can’t imagine how many sexless dates this show might have birthed; its attempt to celebrate the triumph of our supposed liberation clashed too strongly with the anemic and anxious nature of the art, and failed to acknowledge that queerness is as much about trying and failing as it is about winning. Each room felt like an apologetic coming out; all the straight people looked awkward and unnerved, all the gays attempted desperately to assert themselves, looking, and failing, to find themselves represented.

What “Queer British Art” confirmed is that gay identity in England is still rigidly determined by class, and has been long before the 1967 Act came into force. Homosexuals are something that the middle class are, while gay sex is something that the working class did. Quentin Crisp, the actor, raconteur, and pioneer of gay visibility in the period before the Act, was fond of recounting his “great dark man” theory of general homosexual unhappiness: we search for a pillar of masculine virtues, strength and power, whom we can love and will love us back. Yet, in finding that love returned, the great dark man demonstrates his failing as a real man, because no real man would love a homosexual. The class and racial inflections here are unmistakable: the great dark man is the working-class man, who can never have a homosexual cultural identity of his own. The working-class voice is secondary to his desired body — literally, in the case of Forster, who while writing Maurice had to ask his friends how a working-class man might speak when having sex.

These dynamics of partial recollection are at risk of being perpetuated in our own remembrance of what we today call our “queer history,” a cobbling together of scraps of love letters, partially forgotten stories, and court records. An Oxbridge history of queer British culture and persecution can never be enough, not least in the post-Brexit Britain of 2017, when class inequalities are widening and gentrification is obliterating the more transient culture of urban queers. Still, in the cruel, voiceless and chokingly oppressive sexual culture of England, who can begrudge the upper- and middle-class gay men who managed to get out any words at all, even ones they let linger on yellowing paper in locked drawers until after their death? Queers of all backgrounds struggle, both together and against each other, for space to be heard. In this cloistered and sexless context, Forster’s sensitivity to the body and the world is all the more remarkable. His most famous imperative, from Howards End — only connect! — might remind us that while gay histories owe more to the arts of divination than to the science of the academies, they remain a vital tool for understanding ourselves.