Beauty and the Beast

by Amanda Rees

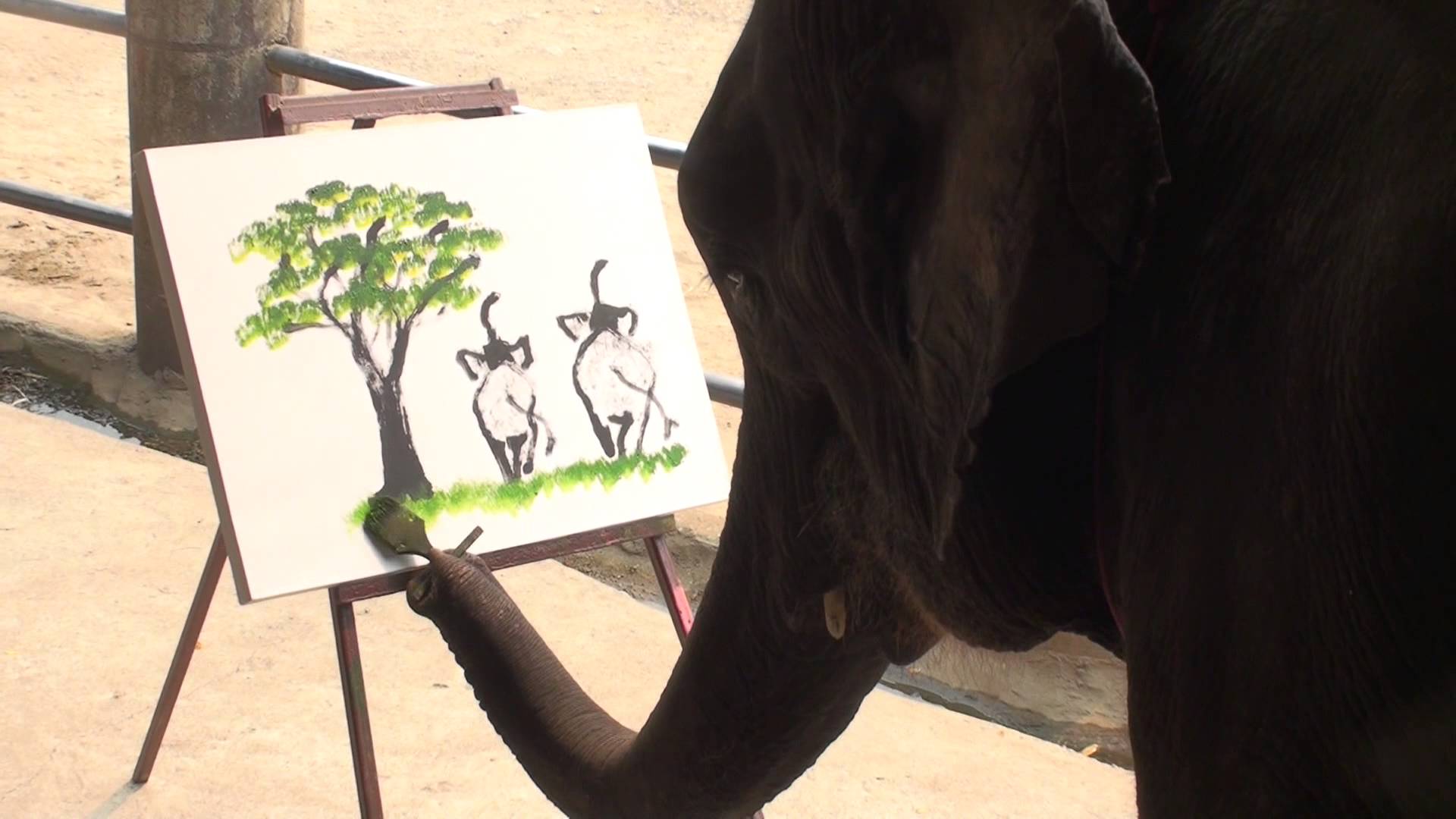

An elephant paints a pastoral scene in a Thai zoo. 2015.

When extraordinarily realistic drawings of animals were discovered in the prehistoric Spanish cave known as Altamira in 1879, scholars initially dismissed them as a hoax: surely “cavemen” could never have produced such lifelike depictions of bison, horses, and aurochs? Well, they had — and alongside the recognition of their authenticity came an acknowledgment of the common humanity we shared with these ancestral artists, who, in some ways, were actually better than us at realism. Their animals had their hooves moving in the right order, a feat beyond even Leonardo. To a hunter’s eye, accuracy was everything: animal spirits might have been magical, but it was the meat that mattered.

Fast forward 35,000 years to “Art and China After 1989,” seen at the Guggenheim last fall. Three works of art were withdrawn, in an extremely unusual act of censorship, after what the museum called “explicit and repeated threats of violence” from animal-rights activists. All showed live animals in various states of distress, but it was Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s video of pitbulls tied on treadmills and facing off against each other that most appalled New Yorkers. (Dogfighting is a profitable and sociable pastime in China: the original performance produced no such revulsion in Beijing in 2003.)

In both of these cases, thousands of years apart, images of animals were being used to sustain human spiritual and economic needs. The shock of the Guggenheim exhibition lay in its presentation to an urbanized world, where a passionate public commitment to animal rights sits uneasily alongside a conscious ignorance of the lived reality of livestock. People eat more meat now than ever before, often produced under conditions that viscerally horrify individual spectators — but which we tolerate so long as they remain socially invisible. Sun and Peng’s dogs may have suffered less than McDonald’s chickens, but scientists and artists, working in public, are supposed to be held to more stringent ethical standards.

Yet the outcry at the Guggenheim, which was followed this year by a vociferous viral campaign in France against Adel Abdessemed (his film, in which chickens appeared to be set on fire, was withdrawn from the Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon), has missed a critical point: our understanding of “animal rights,” which gathered steam in the west in the late 1960s and 1970s, was accompanied by crucial transformations in how we understand the concept of “animals,” “art,” and “humanity.” Before the late 1960s, artists working with animals tended to treat them as mere means, and they were more often than not dead: think of Salvador Dalí’s lobster telephone, Robert Rauschenberg’s paintings with a bald eagle or angora goat, or Hermann Nitsch’s gross-out performances with bloody lamb carcasses. Yet the most interesting art involving animals of the postwar period has treated other species as participants in creation, rather than mere tools in an artist’s hands. Think of the Arte Povera figure Jannis Kounellis, who brought a dozen horses — the animals that made city life possible — into a Rome gallery in 1969, letting them munch on hay and relieve themselves on the black tile floor. Joseph Beuys, in 1974, shared a gallery with a coyote for three days as a means of reflecting on politics and nature. Other recent approaches to animal art have exploited non-human physiological and sensory capacities: encouraging honeybees to sculpt with wax, using different odors to tempt insects into congregations in glass chambers, recreating in 3D the flight of moths through the air.

Conceiving of these animals as participants, rather than mere instruments, in artistic creation can help to counter some animal-rights activists’ blanket rejection of art involving animals. But can the animal be described as an “artist” in any of these cases? Desmond Morris, author of The Naked Ape, discovered Congo, the chimpanzee at the London Zoo whose paintings ended up in the collections of Picasso and Miró. In 2012, the Slade School of Fine Art and University College London collaborated to produce a well-received multispecies art exhibition, featuring abstract paintings by chimps, gorillas, and orangutans. Concerns for animal welfare have meant that many zoos have given animals access to creative materials as part of enrichment programs, meaning that even hissing cockroaches have been able to make their artistic marks. Some animals, particularly elephants, are trained to produce the same picture again, and again, and again. The eager-to-buy audience is delighted. Is the elephant?

Lyrebirds listen to the sounds around them and sample them in their songs — even, pitifully, the roar of chainsaws. Bowerbirds use found objects to create displays that attract others. Is evolution producing art, things that we humans find satisfying and challenging to see and hear? Humans depict the world as it is not, sometimes in order to show it as it more truly is; can animals do this? Primatologists, who observe animals without interacting or interfering with their lives, have recorded many anecdotes of animals being deceitful — a capacity that depends on knowing that other individuals see the world from a different perspective. It’s amazing what you learn about animals when they don’t know you’re there.

Human absence, in a very different way, is central to Pierre Huyghe’s 2014 film Human Mask. This disquieting reflection on the Anthropocene shows an unsettlingly empty world where a monkey, hidden behind a robotically perfect human mask, wanders aimlessly on two feet through a desolate Japanese landscape, while a cat — a predator in a posthuman landscape — intently regards the moving target. The video has become a classic work by an artist who has also worked with dogs, fish, and insects — but what impact did Human Mask have on the monkey? Macaques don’t normally walk upright, and ethically aware movie directors are increasingly using CGI rather than living animals in blockbuster films. When do performing animals stop being entertainment and become art? When does art become cruelty? What matters more, the deceptive appearance of public cruelty — as with Adel Abdessemed’s flaming chickens — or the hidden brutality of livestock production?

As it was in the Paleolithic, animals continue to be used to satisfy human needs — but now, the treatment of animals is often used to determine which humans are themselves worthy of consideration. It’s no accident that the artists involved in these recent accusations of animal mistreatment are themselves “foreign.” The outcry at the Guggenheim included racist characterizations of Chinese people; both Huyghe and Abdessemed are French, but only the latter got attacked by the internet’s animal lovers. And, this, too, may be a matter of evolution, specifically our own. The responses to these works were exacerbated by social media’s damage to the humane capacity to listen, to empathize, and to recognize moments of shared human experience.

A prolonged shot through the eyes of the mask and into those of the monkey constitutes the closing image of Human Mask. Is this the compelling and compulsive stare of a parent, or a lover? Or, as naturalists like George Schaller and Vernon Reynolds have observed with apes, an act of aggression? Invitation or threat? Perhaps both: a reflection of the complexity and contradictions of the privileged west’s attitude to ethical judgment, artistic values, and animal agency.