The Price of Shares

by Rob Horning

Twenty years after Relational Aesthetics, the “social” has moved to the smartphone screen — and Nicolas Bourriaud’s vision of a museum of encounters is dead. The museum of the future is emerging in Indianapolis; dumbing down may soon come to be a fiduciary duty

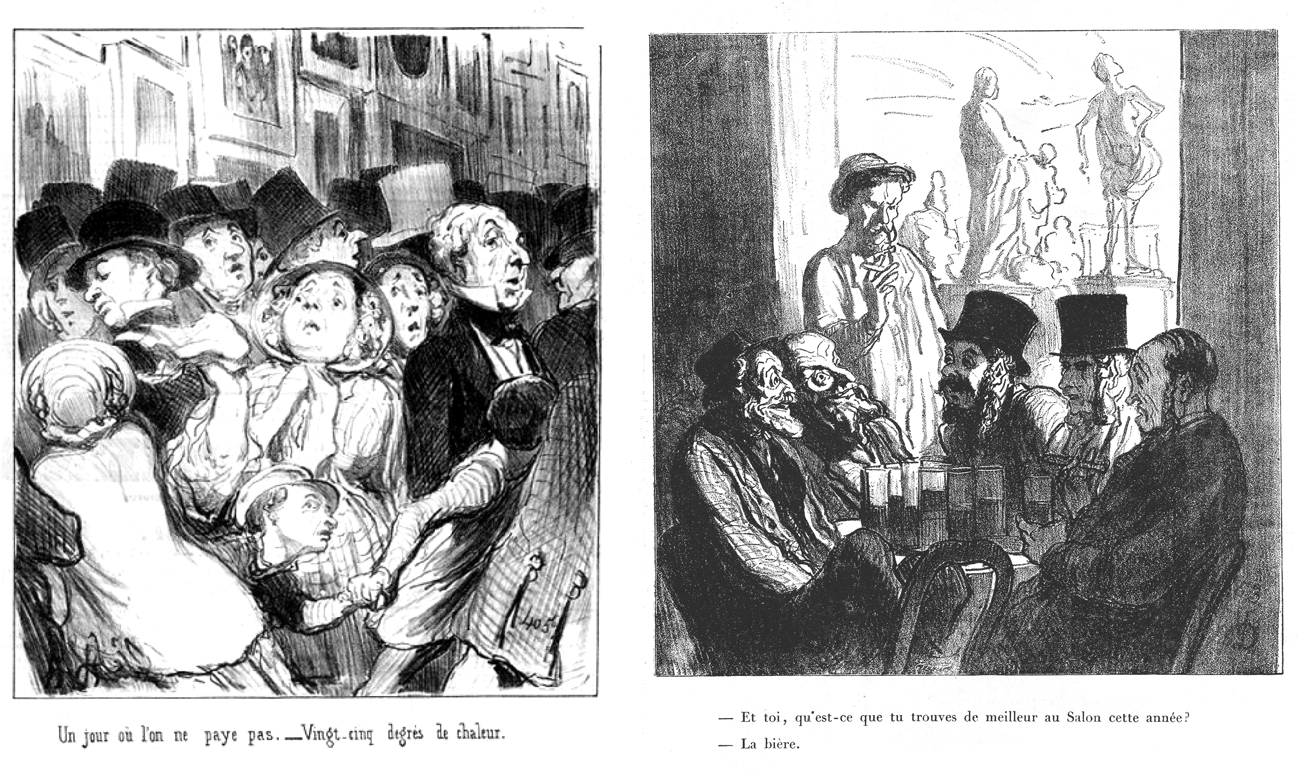

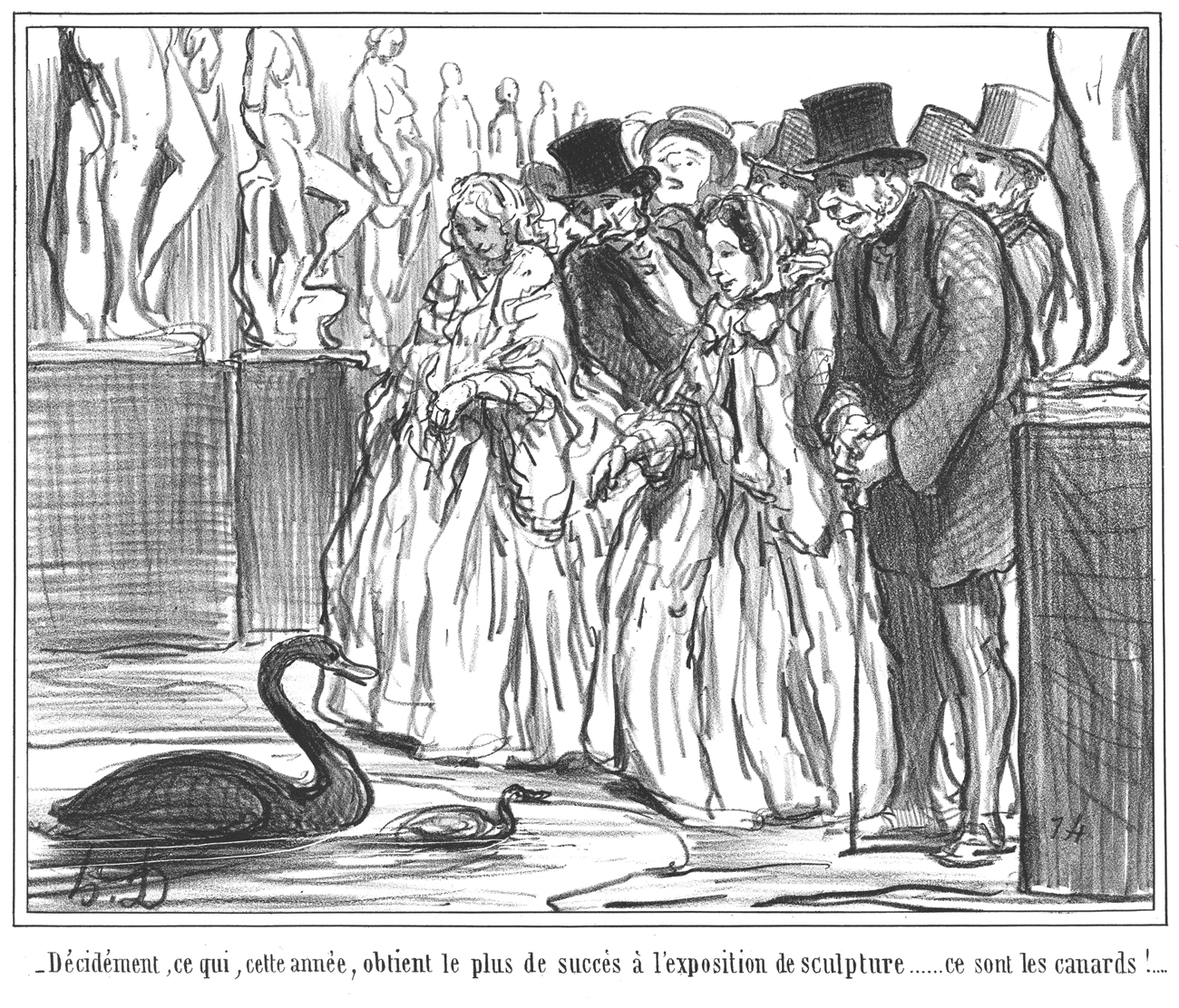

Scenes from the Salons de Paris, by Honoré Daumier.

Left, 1852: “A day with free admission... Twenty-five-degree heat.”

Right, 1864: “So what do you like best at this year’s Salon?” “The beer.”

I.

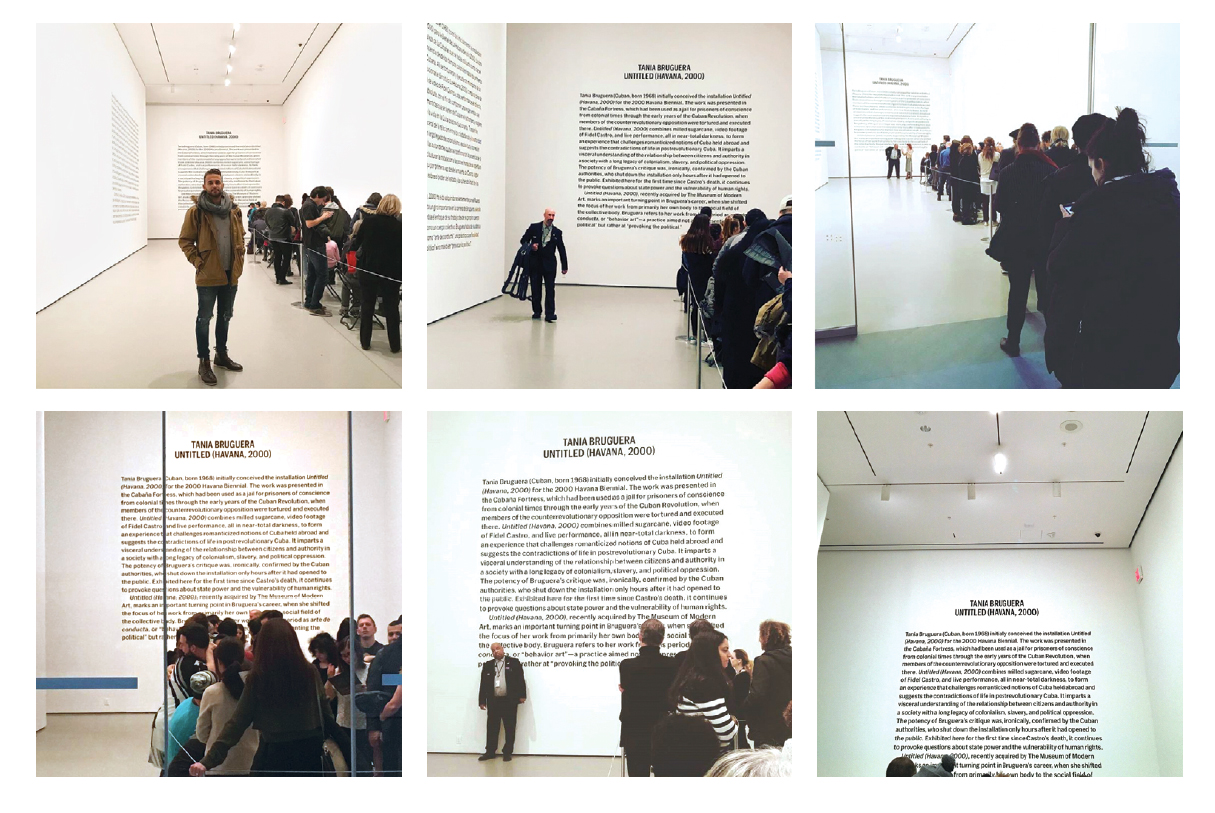

Earlier this year, I took a long lunch break — much longer than I had anticipated — to visit the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which had recently acquired a major installation by Tania Bruguera, the Cuban artist and dissident. Untitled (Havana, 2000) took the form of a darkened alleyway, its floor covered by milled sugarcane; inside were nude performers, visible only in the light from an overhead television monitor playing Fidel Castro on loop. Bruguera had initially created the installation for the 2000 Havana Biennial, where it was installed in the tunnels of an 18th-century fortress that had been used as a site for the internment, torture, and execution of political prisoners during the Cuban revolution. (Che Guevara is said to have personally directed the firing squads.) The biennial had barely begun when Cuban government censors shut down Bruguera’s installation. Now it was in New York, invisible behind a huge white wall.

At MoMA, only four or five people were allowed in the installation at a time, so I joined the long line that stretched beyond the staging gallery on the second floor and into the atrium. I was reminded of the last long art line I had stood in, for Pipilotti Rist’s endlessly Instagrammed show at the New Museum in 2016. The key difference: this line was being monitored. Pacing docents periodically reminded us that the installation was extremely dark, with uneven footing and naked live performers. They emphasized that phone use of any kind was strictly prohibited inside. It wasn’t prohibited in line, of course; almost everyone standing near me was scrolling through something. Being online goes so well with being on line.

MoMA had produced a brochure to be read while we waited, in which Bruguera explained that she intended to make her audience feel not only vulnerable — stumbling around in the dark has that effect — but also complicit. She said: “The length of the passageway provided the time needed for your eyes to adjust and start seeing what had been invisible — and this is the turning point of the piece: the moment you can’t ignore what is happening anymore, the moment you cease to be a visitor and become a witness, an accomplice.” The long wait to get in was part of the design, too, meant to evoke the lines ordinarily experienced by Cubans. But here it felt familiar for different reasons, like the lines I see outside a brunch spot or of people waiting to buy gelato. It made me think of popularity and opportunity cost, rather than economic scarcity and political control. It made me think of the rationalization for living in New York that I sometimes resort to: that inconvenience is actually glamorous.

Eventually I made it into the installation, turned a corner, and found myself in darkness. As promised, it was hard to see and walk. The atmosphere was a bit like a haunted house; I knew there were naked men lurking somewhere, and I half-expected them to make a sudden move, to try to startle me. As I gingerly approached the sole source of light, a small television screen displaying a newsreel of Fidel Castro opening his shirt during a public address, I realized that phones were prohibited not to discourage photography, but because any other light source would ruin the effect. For a moment, I found myself huddled around the TV with four strangers who had been my companions in line for more than an hour. Our time together was almost over.

At that moment, I felt an entirely unexpected pang of nostalgia for the line. Waiting had made up the bulk of my museum experience that day, and I suddenly wondered if I should have taken the opportunity to have a social encounter of some kind, instead of playing games and scrolling through Twitter. If Nicolas Bourriaud’s claim in Relational Aesthetics (1998) is correct — that “it is no longer possible to regard the contemporary work as a space to be walked through” but “a period of time to be lived through” — then my durational performance in the line could have been an instantiation of what he considers the modern urban experience of being-together. That is, if it were not for my phone, which removed me from my surroundings and made me a spectral presence in a different sort of crowd, one that was widely dispersed but responsive to my summons whenever I unlocked my home screen. The line was central to Bruguera’s work, but the phone was central to my experience of the line.

If Bruguera wanted to force me into the “realm of the political,” my phone kept exerting a centrifugal force. Even in a museum I’m always, in some way, connected, networked; my phone negates any effort to lift me to a transcendent plane of aesthetics or push me into a discomfiting social encounter with strangers. Phones promise a range of social experiences, opportunities to chat, flatter, impress, bully, seduce, or ignore other people. They let me calibrate my sense of personal distance, the degree to which I engage with what’s going on, make myself a lurker or a participant. The fact that I couldn’t use it inside the installation did not make me forget about it. In fact, I became even more conscious of it — the supposed enemy of aesthetic focus and bodily presence — and the curious sort of safe space inside the installation where I was forced to be free.

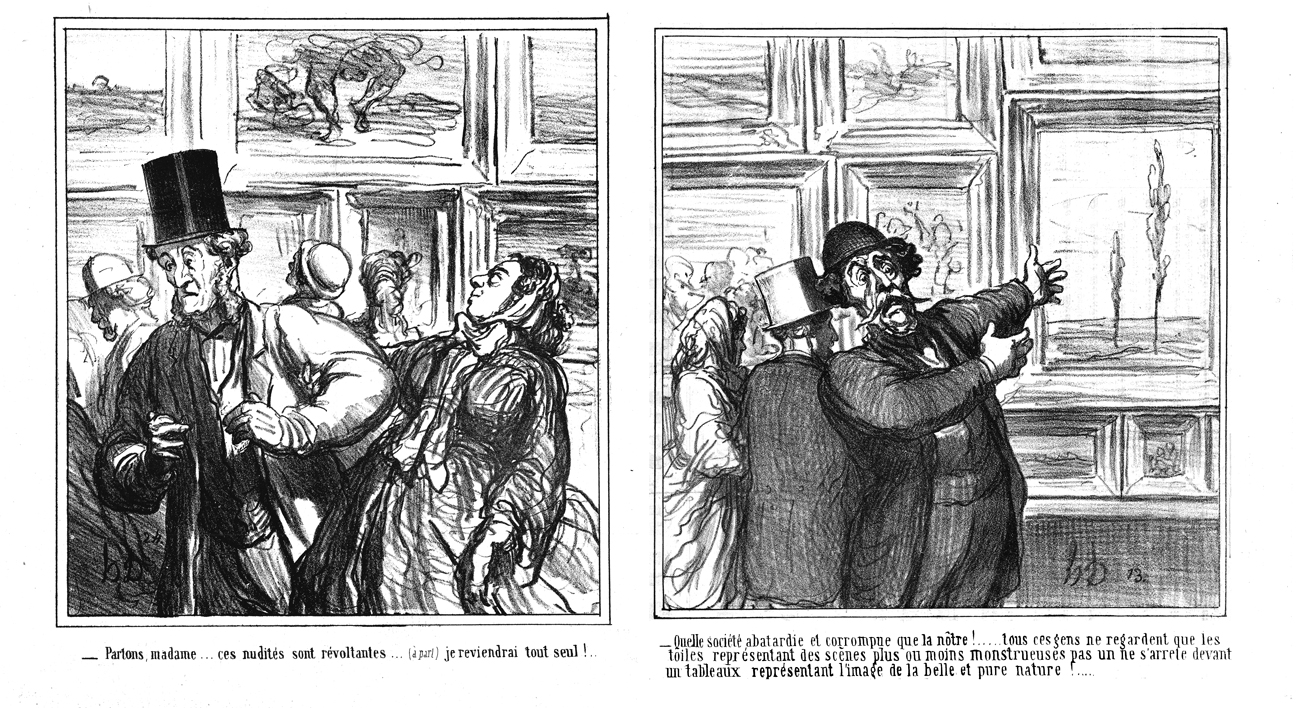

Left, 1866: “Let's go, madame, these nudes are revolting… I‘ll come back later on my own.”

Right, 1865: “What a degraded and corrupted society we live in! All these people are looking at paintings of more or less disgusting scenes, and not one stops to look at a painting that represents beautiful, pure nature!"

II.

MoMA’s decision to acquire a work of art that is impossible to photograph and expensive to produce — it requires four Cuban performers and swathes of fumigated sugarcane stalks — suggests that the museum is trying to appear high-minded and serious in an era when other institutions are resorting to social media-friendly spectacles. Unsurprisingly, art museums have turned out to be popular places for taking selfies, which frame the individual as “art” amid art, or appropriate the brand value of the institution and its most recognizable works. Though museums can prompt visitors to engage with social media platforms, it’s a mistake to interpret this as engagement with the museum or its contents. It’s more an encounter with the platforms’ metrics-driven incentive systems. It is easy to count the number of visitors who use a museum’s hashtag and consider that a gauge of enthusiasm; it’s far harder to measure what’s gained by standing for a few minutes with naked men in a darkened tunnel, watching footage of Fidel Castro.

That’s not to say social media is destroying the integrity of art appreciation, which, after all, has never been the sole mission of museums. But social media disgorges metrics that change how museums are experienced and interpreted, by visitors and administrators alike. The discussion around social media and museums, like the discussion around social media in general, often focuses on the narcissistic compulsion to document ourselves in lieu of paying attention to what’s in front of us. But this critique sets up an untenable separation between our screens and our lives. Our phones not only remove us from our environment, they also allow us to renegotiate our relationship to it — to decide how and with whom we engage. That is, social media has created an expectation that public space is always measured. In the past two decades, museums largely moved from presenting their collections to facilitating relational experiences, and now their attempts to capitalize on the popularity of mobile phones and social media are causing a new shift: from orchestrated physical togetherness to an aloneness together.

Phones posit a distributed sociality online that invades geographic space and turns it inside out, so that your physical location can feel subordinate to the social experience occurring on the screen. There is no longer the expectation that you will interact with other people in a crowd or in line (as opposed to online) at an event, nor that they will meaningfully alter the experience you are going to have. Rather, your fellow queuers are a quantity turned into a quality, online popularity metrics brought to life, certifying the relevance of the experience. This halo effect persists even when social media use is forestalled, as in “David Bowie Is,” the touring exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum through July. You can’t use your phone — but that’s because visitors must wear location-sensitive Bluetooth headphones that pipe information into their ears. We all pay our solitary homage to a celebrity, despite milling about awkwardly in a crowd. The selfie walls come before the show, in the waiting area.

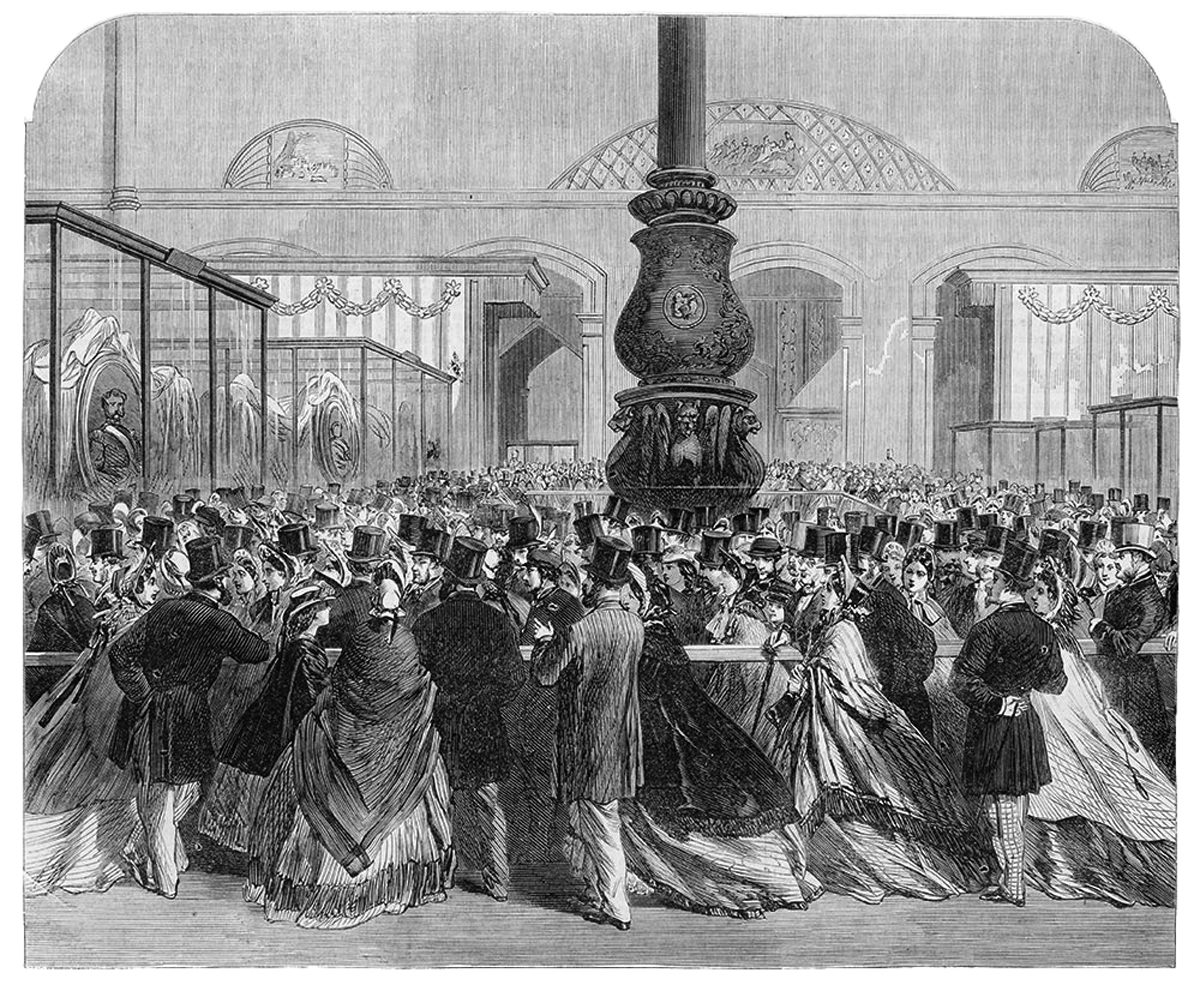

Museums — not only art museums but also museums of history and natural science — once carried with them the promise of education and cultivation. These institutions were premised on an unexamined contradiction: they believed they could bestow “good taste” on the masses, even though this sense of refinement was ultimately predicated on the existence of an established cultural elite, what Clement Greenberg, in his 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” called “the cultivated spectator.” The idea that ordinary people might bathe in aesthetic beauty and somehow arrive at a deeper humanistic understanding was always an alibi for something more basic to social control: deference to one’s superiors. Nineteenth-century reformers hoped that institutions like the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria and Albert Museum) could be places of social betterment and instruction for the working classes, but the collections, anchored in aristocratic patronage and requiring aesthetic discernment, sent a different message. The museum allowed the masses into the presence of certified artistic “treasures,” but such visitors were expected to respect what they didn’t quite understand, out of a sense of duty, and to know that their lack of social and cultural capital meant they would never be at home there.

Long into the postwar era, however, museums did provide a safe harbor from the rising tide of consumerism and the commercialization of various forms of pleasure. Though they may have neutered modern art of any of its revolutionary implications, museums nonetheless preserved a space in which value was experienced as guaranteed not by the market but by (aristocratic) traditions of taste, patronage, and scholarship. And they could be justified as educational institutions: they passed down the “correct” notions of what is canonical and what isn’t.

The putative democratization of these institutions in the late 20th century meant opening them to the vagaries of the experience economy. In his book In the Flow, Boris Groys argues that the museum, in abandoning its emphasis on its permanent collection, “ceases to be a space of contemplation but rather becomes a place where things happen.” He is thinking primarily of “temporary curatorial projects,” but much of what now “happens” in museums could be characterized as shopping. Today, the function of museums is not to overawe visitors so much as pander for the attendance statistics that can attest to the museum’s viability as a marketplace of attention. (Or, indeed, as a literal marketplace: gift shops now provide the largest share of total income in American museums and are far more profitable than museum restaurants.) Museums face a similar challenge to that of cash-strapped universities, and a similar dilution of mission. The curatorial and quasi-educational aspects of museums now account for less of their operating capital and square footage and occupy a correspondingly diminished place in the public’s awareness. Instead, it’s easier to view the museum as a sort of retail showroom, a sales medium that must compete or co-brand with other sales media to help sell tickets, memberships, tchotchkes, advertisements, and other forms of sponsorship. They no longer serve as a respite from commercialism but as its wellspring, replenishing its pool of symbols of aspirational prestige.

This has been true at least since the onset of the era of the museum blockbuster — King Tut brought 1.27 million visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1979 — and onward through the advent of Guggenheim Bilbao in 1997 and Tate Modern in 2000. But the practice of shopping is itself undergoing a transformation, as consumers learn new ways of performing the self on online platforms. Shopping has become a form of production — of the self, of trends, of data, of spectacle — as well as of consumption. This, in turn, has changed what museums think they have to sell, and how they try to sell it.

Twenty years ago, Rem Koolhaas could already proclaim, in his notorious competition entry to remake the Museum of Modern Art as “MoMA Inc.,” that “the very success of the museum as an institution — a pivotal center of contemporary society — threatens to engulf its prime function: the organized contemplation of art.” He proposed that MoMA become an “urban apparatus that enthusiastically invites the recent era’s unprecedented numbers of museumgoers and explores new conditions of artistic production without compromising traditional museum functions.” Koolhaas’s vision aligned with Bourriaud’s contemporaneous claims, in Relational Aesthetics, that art was undergoing a process of “urbanization,” with individual paintings, sculptures, and even new media being supplanted by art as an “arena of exchange.” The museum soon became a space to eat Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Thai curries, to debate philosophy in Thomas Hirschhorn’s cardboard bivouacs, or to get down on Piotr Uklański’s dance floors.

Left: Piotr Uklański. Untitled (Dance Floor). 1996. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Right: Carsten Höller. Mirror Carousel (2005) and Test Site (2007), on view at the New Museum in 2011.

Even assuming that museum visitors actually wanted to be participants in and not consumers of art, social media now offers an “arena of exchange” on a scale that makes the ambitions of relational aesthetics seem mundane. Not only can phones provide information — and most museums are eager to have their custom apps installed on visitors’ devices — but their camera feature also provides a failsafe way to “participate” in art. Museums are no longer spaces in which to experience art, but rather spaces in which to perform the self having art experiences. Accordingly, curatorial choices are now geared toward encouraging museumgoers to promote their visit. Museums, as they latch onto social media to boost their metrics, have become an appendage of the phone and its platforms, their ways of engaging users, their algorithms for gratifying consumers.

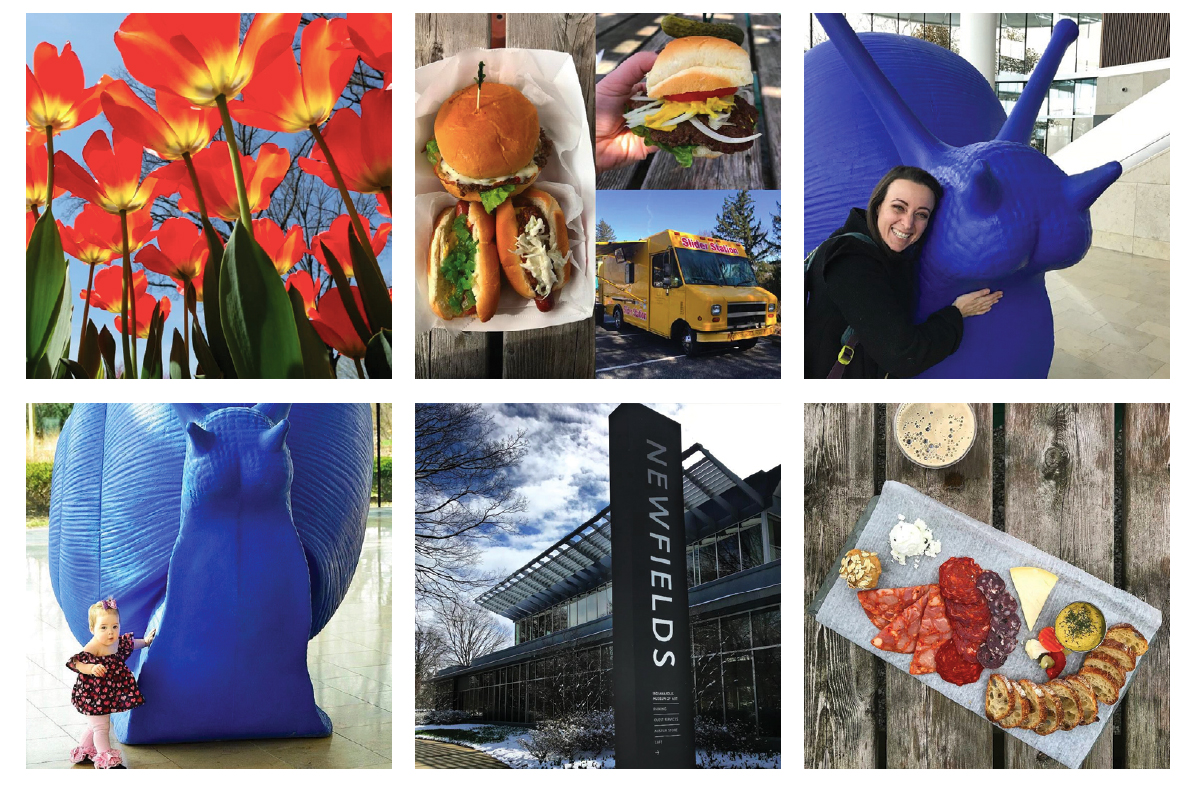

These changing conditions are perhaps most explicit in the recent conversion of the Indianapolis Museum of Art into something called Newfields, which, its website states, is “ideal for performances, afternoon walks, kite-flying, cloud-gazing, memory-making, new-idea-having. There’s a mansion to stage unforgettable events, restaurants for relaxing, bars for microbrews and friendships. Newfields is a setting where it’s easy to make connections of all sorts.” As the reference to “connections” suggests, Newfields has been conceived not so much as a museum but as a kind of social media platform. The idea is to mimic the internet so as not to compete against it, and to leverage social media to out-compete other local destinations as a place for photo-ops and other personal branding opportunities.

This change has been orchestrated by Charles Venable, who took over as director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2012. He replaced Maxwell Anderson, a former director of the Whitney who had sought legitimacy for Indianapolis in the global art world — the museum organized the US pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2011 — and support from local audiences beyond the donor class. To that end, Anderson had eliminated the museum’s admissions charge — an approach more suited to museums in wealthier cities with larger endowments and a more robust philanthropy circuit. When Venable arrived, the museum was funding itself with debt loads that the board deemed unsustainable. So far, his answer has been to pursue a suburbanist strategy of making the familiar seem exclusive, expensive, and “fun.” This is not unlike the Instagram influencer strategy: be photogenic in conventional and immediately recognizable ways, and then await the likes that bring the crowds.

Newfields is not alone in this approach. As the critic Benjamin Schneider recently wrote, “In urban space, our desire to photograph and share virtually everything has spawned a new genre of urban pleasure grounds. They specialize in Instagram bait, a hybrid of ultra-popular immersive art like ‘Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors,’ and increasingly ubiquitous brand activations.” Works of public art, by this logic, coexist with non-art objects that serve principally as backdrops: consider the trend of large, freestanding signs of cities’ names, as with the TORONTO sign by its city hall, or the huge AMSTERDAM sign outside the Rijksmuseum. These effectively function like Snapchat filters, captioning one’s tourist photos without upstaging the tourist. Are these freestanding captions any different from Anish Kapoor’s bean sculpture in Chicago’s Millennium Park, which offers a funhouse reflection of congregated tourists taking souvenir snaps? These large sculptures and installations celebrate the idea that crowds of tourists are more significant than any singular work of art. They draw visitors and elicit social posts not because of any aesthetic qualities; people go to them to be reminded, at least implicitly, that their own metastasizing presence is better and more interesting than that.

III.

Social media and museums, on the surface, do have a lot in common. Both are, after all, fundamentally archives with exhibition spaces. Both share a preoccupation with “authentic content” and “meaningful expression,” to borrow some of Facebook’s language for what it claims to provide its users. But social media and museums go about supplying “authenticity” in necessarily different ways that, when combined, negate each other. What is authentic in social media relies not on provenance but appropriation: using borrowed or staged images to say something about your own identity.

“Traditionally,” Groys writes, “the gaze of the spectator was directed from the outside of the artwork towards its inside.” That is, the spectator was expected to look at art and try to understand it. But the pretense that the spectator is an elite or would-be elite who seeks the requisite training to enjoy the aesthetic experience has been nullified. “The gaze of the contemporary museum visitor,” Groys continues, “is, rather, directed from the inside of the art event towards its outside — towards the possible external surveillance of the event and its documentation process, towards the eventual positioning of this documentation in the media space and in the cultural archives.” That is, visitors now come to think about their own place in the event they have elected to participate in.

This “documentation” is not merely the neutron-bomb installation shots that Brian O’Doherty points to as the essential expression of the white-cube ideology: a depopulated view from nowhere, now prominent on sites like Contemporary Art Daily. Nor is it the sort of official ephemera that outlasts performance pieces and temporary installations. It is mainly a matter of the documents we produce ourselves of our visit, and the role they play in our archives of the self, which loom far larger in our individual lives than any collective archive meant to represent a culture — another moribund notion of a museum’s purpose.

Social media posits a different sort of culture, in which atomized individuals share with one another not a set of inherited traditions or universal moral values, but rather an orientation toward “content,” appropriated and circulated in a homogenized form under the banner of one’s own identity, and subsequently assessed in numeric terms. And it is this conception of culture, in which all art is reduced to a kind of shareable content, that has begun to govern our white cubes — nowhere more so than in Indianapolis, which may prove to be a harbinger of museum practice in the 21st century.

Facebook, Twitter, and the rest have a common business model: gather data on individuals’ tastes and use it to help advertisers target consumers. Newfields, by recasting itself as not a repository of timeless values but a competitor in the experience economy, is surrendering to this model — and in the process surrendering its own curatorial agenda, the traditional source of a museum’s authority, if not its reason for existing. “Our beer garden experience was a big success,” Newfields’s board chairman Tom Hiatt told the Indianapolis Business Journal. “In my view, it’s important for us to build on that and mini golf and make even more friendly experiences — to broaden our menu.” Newfields has raised admission prices to $18, fired (or encouraged the departure of) senior curators, and hired a “director of hospitality” and a “director of festival, performance, and public programming”: a rejection of art knowledge in favor of people-pleasing.

Newfields has shed the stigmatizing “museum” label — a repellant and alienating word, according to Venable, who has surveys to prove it — and has instead fully embraced the idea that it must justify itself according to a new set of criteria. Its peers and competitors are no longer just the Met, the Art Institute, or the Getty; rather, they are all the other entertainment options customers might choose instead, whether historical museums, tourist attractions, theme parks, restaurants, movies, concerts, or increasingly moribund shopping malls. “When you think about it, ‘museum’ is an old word that conjures up images of an indoor experience — passive, looking at art on the walls, sometimes being exhorted not to touch the painting, wandering around in a hushed environment,” Hiatt told the Indianapolis Business Journal. “That, frankly, is an experience which a lot of people don’t find welcoming or engaging.” (That sort of rule-abiding, passive experience was precisely what had been provoking me at MoMA. The Bruguera installation went against the grain of the sort of crypto-empowerment that other experiences, especially the experience of using my phone, provide. That friction was the entire point.)

Unlike the democratic vision of Bourriaud, the Newfields philosophy is populist. From the point of view of Newfields’s director and board, museum visitors certainly don’t want to feel any responsibility for art. They want to be part of the crowd, so that, when they share pictures online, they can feel as though they stand out. This is a key difference from the appeal in the late 1990s and early 2000s to art as shared encounter, when museums like Tate Modern or the Palais de Tokyo were imagined as places to experience some surprising form of social relation. Now, instead of art being a social activity in its own right, other social activities — from beer halls to mini-golf — are organized around it, with the art serving mainly to lend an aspirational glamour to the digital documentation of one’s free time. Time spent with the art is meant to be “social” only in the sense that phones and social media make everything potentially social. Though one’s embodied experience of a show might entail isolation via headphones or a preoccupation with one’s Instagram feed, to observers on the other side of the screen it will appear as though one is happily ensconced within a crowd: social participation without the bother of dealing with other people.

Newfields claims that it faced economic pressures that made its transformation unavoidable. And Venable, for his part, has justified his erasure of the museum in language that Bourriaud might find familiar. “Art was always an experience,” he told the New York Times. “A Rembrandt painting was a personal experience. But the bottom line is, I can’t make someone a lover of Rembrandt if I can’t get them to ever come here.” That seems disingenuous — mere exposure to art isn’t going to convert anyone into an art lover — but at least he is honest about the criteria that now govern the institution. A Rembrandt does not derive its value from being appreciated and interrogated, not anymore at least; instead, its worth is determined by the size of the crowd around it. “I think if the art museum industry does not follow the lead of other industries, there is a looming crisis in which galleries full of the world’s truly greatest creative art will be empty,” Venable told the Times. “And that is not going to happen here.”

IV.

What Newfields points to — and what Bruguera’s installation at MoMA signaled as well, through an act of disavowal — is a museum not just curated for social media, but one that fully embraces social media’s measures for success: crowds, attendance figures, lines. These don’t require interpretation, but instead promise a sense of immediacy, and an attendant fear of missing out. Metrics become a more intuitive form of aesthetics, which might seem to position Newfields as a quasi-democratizing force, bringing people together with art on their own terms. But in conducting user surveys and adapting the way space is branded, the museum is not trying to lend dignity to visitors’ taste — whether it is for kitsch or for anything else — so much as further indoctrinating them into social media’s viral imperatives. Getting attention is more significant than paying attention.

As has been widely pointed out, this metrics-based cycle has tempted some museums to present hashtaggable Instagram-bait installations that look like but aren’t quite art — the Rain Room, acquired by LACMA last year, is perhaps the most notorious example — and has inspired some cynical entrepreneurs to create knock-off “installations” like the Museum of Ice Cream, which is not a museum at all. Brands, too, are in on the act: the 2015 pop-up “Museum of Feelings,” in New York, featured rooms imitating installations by Kusama and James Turrell, all in promotion of Glade plug-in air fresheners.

Whether inside or outside the museum, these art-like spaces feature brightly colored or strikingly patterned backgrounds against which one can pose, providing a ready-made activity for the groups who attend: you take pictures of each other. The resulting images straightforwardly foreground the intention of wanting “interesting” pictures to post; in a sense they are about that desire to be interesting, regardless of what they depict, and that is the most interesting thing about them. For these metrics have nothing to do with experiential immersion; what matters is “engagement,” which, in social media’s terms, is a strictly numerical matter. Hence, Venable doesn’t make the case for Rembrandt by referring to the history of Dutch painting, or even to abstract virtues like beauty; he points to the attendance figures, to the connections the Rembrandt can produce.

...and at the knockoff Chris Burden at Rabbit Town, in Bandung, Indonesia. 2018.

But if Rembrandt is only significant because of the crowds, because it convenes a documentable event, then the art itself can fade to the background, or even be entirely simulated. This may sound like a far-off Zuckerbergian nightmare to curators and artists, but in fact this is already happening abroad. Consider Rabbit Town, an Indonesian tourist attraction that lets visitors photograph themselves in recreations of Kusama’s environments or Chris Burden’s Urban Light from outside LACMA. Rabbit Town also has backdrops that were ripped off from the Museum of Ice Cream. Here, no distinction need be made between art and non-art. A backdrop simply needs to look noteworthy or like-worthy.

Right now, it’s easy for Rabbit Town and Museum of Selfies and so on to compete with art museums in providing “fun” quirky backdrops, but their moment seems likely to pass: they are too self-evidently contrived to have much lasting appeal. As they proliferate — and there is nothing preventing them from being widely copied — these backdrops will come to seem tired and obvious, marking those who post selfies from there as try-hards. Art museums can provide vivid backgrounds that are less arbitrary, since they distill cultural tradition into recognizable tableaux that allow visitors to draw on them for their own status. Social media commits the museum to that logic of celebrity, as visitors assign themselves the role of paparazzi to the instantly recognizable works they jostle to be near. This is the logic of lines and crowds: lines must be worth waiting in, crowds are obviously worth joining. Nowhere in any of this is art required to convey anything other than its own notoriety; it doesn’t require interpretation or focused attention, let alone any kind of collective engagement.

V.

At some point this century — perhaps already, if Venable is right — it will become the fiduciary duty of art museums to embrace the attention economy, which phones make inescapable both as a logic (what is popular is what is valuable) and a way of being (seeking attention gives our behavior meaning and momentum). This means leveraging whatever vestiges of prestige can be squeezed from art while obliterating the system of aesthetic values that, at least in theory, initially secured that prestige. Works justify themselves by being already known, not by what they express or how they express it.

We can dispense with the idea that visitors come to museums to experience transcendence, or to cultivate their eye, or to participate in a novel social configuration. Instead, visitors are presumed to be “brand ambassadors,” affiliate marketers who will eagerly promote an experience in exchange for perceiving themselves to be influential. Therein lies the prestige potential of museums, a residue of their former association with the reserve aura of luxury and exclusivity. Museums now aspire to be inclusively exclusive: large attendance, crowds, and lines, which secure the impression of popularity and scarcity in transmitted images from the scene.

As I waited in the Bruguera line, I took a picture of it and texted it to a friend, with a caption: “Why am I here?” But in a sense, that message was its own answer. Waiting in lines, jostling in the crowd — the audience that can’t afford the exclusivity and elitism in art appreciation can enjoy instead the contradiction at the heart of social media: networked individualism, being alone not in the crowd but through it. The museum should now be understood in these terms — not a place to look, or to feel, or to learn, but a place to wait until a sense of your own significance closes in on you.