An interview with Camille Henrot

Camille Henrot. The Pale Fox. 2014.

All works courtesy the artist; Kamel Mennour, Paris/London; König Galerie, Berlin; and Metro Pictures, New York.

Apps promise spiritual perfection, God and your dead dog have Twitter accounts, the juice bar at your gym sells magic immunity powders: is there any doubt, this late in the game, that we were never really modern at all? For the French artist Camille Henrot, the discipline of anthropology, despite all its baggage, offers an essential tool to parse today’s world, wider than ever but not nearly as advanced as we think. In installations, drawings, frescoes, and videos like her rollicking Grosse Fatigue, which netted her the Silver Lion at the 2013 Venice Biennale, Henrot reveals the core human impulses beneath our supposedly new technologies. Our museums and our social profiles are exposed, with ruthless clarity and immense wit, as inadequate but also irresistible.

Henrot was born in Paris in 1978, graduated from Arts Déco in 2002, and spent a few years shooting commercial photography and music videos before embracing art full time. Early photographs and sculptures gave way to complex assemblages of antiques, remnants, and straight-up junk — the product of Henrot’s avowed eBay addiction, a heavy lift for the movers when she came to New York in 2013. When we caught up this August, Henrot had checked out to a speck of a Greek island, far from the European mainland, before the final push to the biggest show of her life: an early retrospective at the Palais de Tokyo, filling the entirety of France’s largest museum. Her style of conversation, like her art, is both theory-laden and playfully light, and flits between French and English depending on the hour. Her humor is natural, but it’s practical too: the keenest of weapons when politics is no joke.

× Jason Farago

So here you are on this island, lost in the Mediterranean, closer to Turkey than Greece. One thread in your work is travel — all the way to Vanuatu, or to New York — and I want to start by asking about wanderlust. Have you had it since you were young?

When I was young I couldn’t travel, because my mother was afraid of flying. The first thing I wanted to do as a teenager was travel. I like to go where I don’t belong. I feel stimulated through being uncomfortable in a new place and surrounded by things that are unfamiliar, that I don’t understand so well. There is a virtue to not being in a comfortable place when you work as an artist.

When you travel, your perception of yourself immediately changes: suddenly you become an archetype, and the complexity of your identity disappears. To a foreigner, I am just French, or a white woman. It makes you realize the power of archetypes and prejudice. You learn not to give so much importance to the way people define you, and for an artist, that opens up space for your own unique decisions and movements.

We’ve talked before about how so much anthropology of the late 19th and early 20th century began less from an academic impulse, and more from a wanderlust among restless Europeans. How did you come to anthropology?

As a teenager, I remember my sister reading Claude Lévi-Strauss, and she talked about it all the time. At that age I felt a bit irritated by anthropology, because I was afraid of it. I knew it was the descendant of colonialism. But my sister insisted it was much more complex. Anthropology has always engaged in auto-critique, from the very beginning. Tristes Tropiques, for example, is less an ethnographic text than an interrogation of how structuralism is built and then deconstructed. Then, when I was 20, I read La pensée sauvage [The Savage Mind, 1962]...

The book where Lévi-Strauss demolishes the distinction between primitive and modern.

And I immediately related to it. I thought it was really a book about art, in a way. It seemed only natural, as an artist, to be interested in anthropology. For a very long time, art history books only had art from the west, which always seemed incomplete to me. I could feel that lack. Until very recently, the art of nonwestern cultures was relegated to the field of anthropology. For me the only way to approach art in a way that embraced a wider scope was to adopt an anthropological approach.

Later I worked a bit for Pierre Huyghe, when he was doing the expedition to Antarctica — and when I was putting together my own first show, Pierre recommended to me Victor Segalen’s Essay on Exoticism (1904). I was very, very interested in that book, and what it meant to philosophize about difference during the colonial era. Because anthropology is a science that can only be problematic. Going outside of your own culture means that you will always misunderstand, and it immediately creates ethical dilemmas — it’s like putting your finger in an electrical socket.

I think anthropology is very much about unsolved problems. There is no essential truth in anthropology, and so it’s a not a discipline that gives you satisfying answers. The question of otherness, for example — “alterity,” as anthropologists say — never gets resolved, except in death. Or God. And perhaps not even in God.

The colonial legacy in anthropology that you’re describing runs through our museums as well, of course. I remember when I was a college student, and I was trying to understand why some art was in the art museum and other art was in the natural history museum. James Clifford writes about this: what is “art” and what is just an “artifact...”

Sure. We know that the museum, the way the museum functions now, is still the product of that time. Even if you look at the representation of women in museums, or the representation of art from outside the west, it’s still the 19th century. Maybe it’s difficult for the museum to change because it was born out of these ideas. You can change the displays, but the legacy is always there. I think that’s one of the reasons that curators and contemporary artists have lately been so interested in museums with older forms of display.

Like the Ethnological Museum in west Berlin, where Juan Gaitán staged the 2014 Berlin Biennale. Or those chilling Congo collections in Brussels.

What’s important to remember is that our story of art was built with these prejudices at its center, and there’s no point in pretending they never existed. It’s the base of these collections: genocide, murders, looting. Many museums of anthropology are full of objects collected on dead bodies. There is still work to be done to address the guilt and the ghosts that haunt these collections, as well as the larger questions that underlie anthropology as a discipline. Even if these things can never be fully repaired. We have to live with the guilt, embrace it, or at least acknowledge it. Hiding from it is just narcissistic.

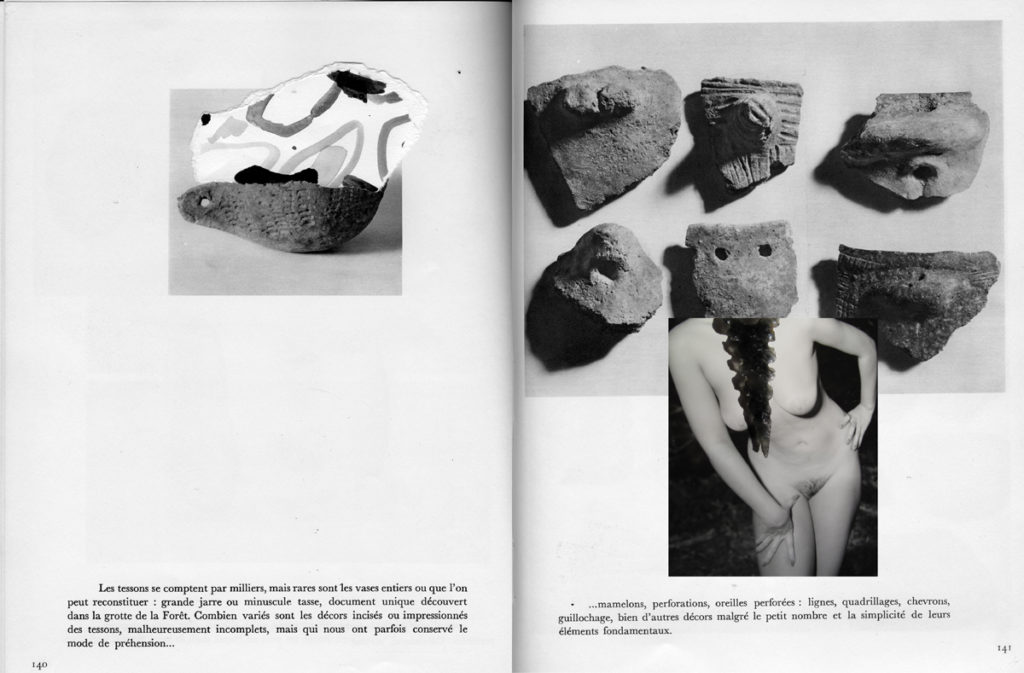

Some of your early works engaged directly with this history of museums and violence. Prehistorical Collection starts from documentation of antiquities in Algeria...

I was very interested in a theory of prehistory, laid out by Michel Lorblanchet in a book called Les origines de l’art (2006). He argues that the perspective we have on prehistory constantly changes, even more than our view on 19th- or 18th-century art. The further you are from a specific moment, the more you have to understand it through a contemporary perspective, and thus the more it needs to be updated all the time.

So, for example, scholars of prehistory wrote for the longest time that cave paintings were the first manifestation of art. But the category of “art” changed after Marcel Duchamp, after the readymade, and so the origin of art had to change as well. The first act of art, by the definition we use today, would now be much earlier: collecting stones and putting them next to each other.

Then I bought a book about prehistoric art on eBay, with a very strange story. I was first attracted to it because the images were printed in this magnificent old style of photogravure. But then the seller contacted me. He told me he was part of the May ’68 movement in Paris, which, as you know, started at Jussieu, the social sciences university. And this guy told me that, at the moment the barricades went up, he broke into the library and he stole this book. And now he was selling it on eBay!

OK, so we need to talk about the place of eBay in your work. Beginning with that project and through to The Pale Fox, eBay seems to function in your art as the B-side of the universal museum. The epistemologies are different — eBay is understood through the search bar, while the museum is organized by taxonomy — but the goal is the same: one place for the whole world’s stuff.

Or perhaps eBay is the opposite of the museum: the objects you decide to get rid of. You don’t need them anymore, or they have an exchange value for another group that’s greater than the emotional value that you put on them.

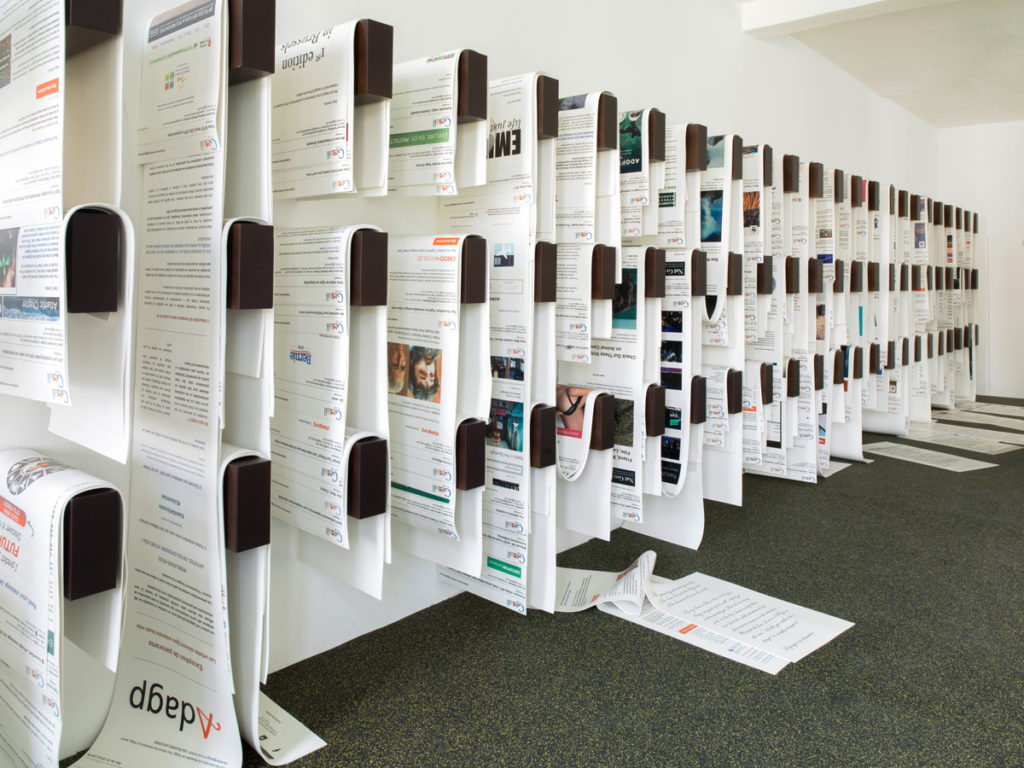

It’s a more honest image of human culture for being messy, and eBay realizes, in some way, what Yona Friedman dreamed about when he wrote about the “museum of the 21st century.” A museum without a director, without curators, where people would form the collections, bring random objects. People would choose what is worthwhile to be conserved for future generations.

There’s a logic to the assembly of the objects in The Pale Fox — keychains, eyeglasses, pinecones, posters of lemurs — but the amount and the variety of things ends up overwhelming you. Its obsessive quality means it can’t be fully rationalized.

I gathered the objects in The Pale Fox over four or five years, not just from eBay but from flea markets. Near where I used to live in Belleville, there was a flea market where people sold things that were not precious at all. Extremely modest. A single shoe, or a telephone that doesn’t work, or a remote control that operates who knows what. I spent a lot of time photographing these combinations of objects, and also buying them.

Then I did the Augmented Objects, for which I covered some of these things in tar — those ones have a weird animism, but they’re very discomforting, too, as the objects had such a short duration of life. An egg beater. A hair dryer. Things you need, but actually you don’t need. You see these objects and you don’t want to see them anymore. Things for drying your clothes. Or sporting equipment that you don’t use because you’re actually no good at tennis. Toys for kids that they never liked. It’s the story of abandonment that I was most moved by. I sometimes feel so attached to objects that I feel empathy for the ones that aren’t loved anymore, even when they belonged to somebody else.

But in the process I found I had all these objects at home. I could hardly move. And then when I moved to New York I had to put all these objects in a box — not even a box, a giant container, because I had so much stuff. I couldn’t get a big enough studio for all the stuff I had; I hadn’t anticipated how expensive space is in New York... [laughs]

This is the classic art history narrative in New York: it’s always about real estate. You see a painter shift styles, you wonder why, and you learn: ah, they got a new apartment...

It’s totally true, and on the side of the galleries too. Oh my god, I remember thinking, if I have a show at one of these big galleries, they’re 25 times the size of my studio! Then I talked to an older New Yorker, and she told me: in my day, the artists had giant studios, it was the galleries that were small...

But it’s true that The Pale Fox is connected to this story of real estate. I didn’t know what to do with all the objects I’d collected. How could an installation take all these ridiculous little objects — a book of crosswords inspired by the Bible, or a pencil sharpener shaped like one of the Pyramids — all these things I’d been acquiring, how could they be organized?

When I came to New York, I was deep in the research of Grosse Fatigue, and I was reading The Pale Fox (1945), by [the anthropologist] Marcel Griaule. He was a huge inspiration for Grosse Fatigue, because he introduced a type of narration that is somehow a superstructure — a story that contains many different types of knowledge.

And the superstructure that governs The Pale Fox — objects are arranged to narrate the development of the economy, or the development of religion — overrides any matter of artistic quality, financial value, prestige. Also uniqueness. You can have a real shark fin, or a keychain of a shark, or a printed JPG of a shark...

Because with a superstructure there is no judgment. It’s a classification that is a critique of classification. Structures seem relevant when they’re applied to a very defined, exact field. But when you try to expand what the structures apply to, they start to collapse in on themselves. So if you follow a superstructure in this hyper-rational way, you end up forcing all the exceptions and paradoxes to emerge.

What I wanted to do with The Pale Fox was find an aesthetic of accumulation that allowed you to feel the structure, and the power of your own interpretation, your own understanding. Where you don’t feel that an authority is talking down to you. Which is always, as a spectator, what I’m reluctant to submit to. It’s probably just a stupid teenager’s behavior — it’s absolutely not valid in terms of museum theory. But that’s the freedom of being an artist, as opposed to a curator of a museum collection. You can preserve the enigma of nonverbal connections among objects.

It’s almost a duty. The world we are living in now is so binary. It’s a world of conflicts and ideologies where everything is presented as an absolute. And as artists, we have to protect a space of nuances and contradictions.

All of us, hardly just critics like me, now face immense pressure to determine whether works or art are right or wrong, good or evil. Immediately. But really good art should make me doubt my own certainties.

In a way the rise of digital culture is responsible for an overgrowth of judgments. Which is good sometimes. But it also becomes sterile, and it rarely comes from a position of modesty, from people willing to change their initial opinion. What about being surprised by yourself, being unsure what to think? Most people who express opinions online only want to convince other people — whereas the person who doesn’t know, who’s reflecting, that’s the voice you want to hear the most! “I’ve been ruminating over this for a while, I’m really unsure of what to say...” Nobody ever says that online!

Actually, the moral languages of online discourse came up in a recent project of yours, for which you wrote to the do-not-reply addresses of dozens of online services.

Office of Unreplied Emails came after a deep moment of thinking about politics and ethics. I was receiving more and more emails from places like Change.org. They communicated in a way I found very compelling, by using my name. “Camille, don’t let the oil companies take control!” Of course not, I can’t let them! [laughs] I felt that I had to do something, and that participating in these causes was more important than my work. I was signing petitions, donating money, and it was never enough.

In the past you wouldn’t be solicited in such a constant way — now, you receive emails about the environment as you finish taking a cold shower because the hot water isn’t working, or you get an email about net neutrality after fighting with your family. Your personal problems and these larger “important” problems become enmeshed, and it’s difficult to resist the anxiety that creates.

So I started writing back. There were moments when I’d get these emails while I was alone in bed at night, desperate or lonely or sick, and I was tormented because I couldn’t find the energy to help every single day. A disparity emerged between the consistency of these emails and my own inconsistency as an individual — one day I want to act, and the next I feel unable. Are we allowed not to be consistent? Is not being consistent a reason for not continuing to help? What are you supposed to do with feelings of powerlessness?

Like you were saying, digital connections — a world where we are profiles before we are citizens — might have made this more difficult. Accepting one’s own inconsistencies, and differences from day to day...

Your own doubts, your own failures. So sometimes I would be asked to sign petitions about topics I wasn’t 100% sure about, especially ones connected to American culture. And in 2016 this increased substantially. The battle of opinion online, as you know, became a lot harsher during the American election; there was less and less nuance, more and more extreme stances. There was something scary about this — the sensation of stepping onto a battlefield if you engaged. But once you’ve started, you can’t step back completely. You’re always le cul entre deux chaises, and you just feel guilty. Sometimes you act, sometimes you don’t, and you live with that guilt.

That’s the feeling I wanted to evoke in Office of Unreplied Emails: the variety of emotions you pass through every day. It was the activist emails that first inspired the project, so there are a lot of those that I replied to. But I also replied to commercial emails.

Didn’t you write back to Fresh Direct?

Fresh Direct, Petco, Chase, Groupon.... A few spam emails too. “Camille, I saw your profile on Facebook, you’re a very cute boy...” [laughs] This fake proximity and intimacy, as a commercial strategy, increases our feelings of solitude. The more we are connected to each other, the more the anxiety of being alone arises.

You showed these emails with a series of frescoes, which depicted pairs of fish, birds, snakes, that supposedly “mate for life.” These also reflect the legacy of anthropology — the side of anthropology that treats man as just another animal.

11 Animals that Mate 4 Life was a separate project, but when I was invited to be in the Berlin Biennale, I thought it would be interesting to associate the two. The emails are about loneliness, heartbreak, and it was interesting to put them alongside these cheesy representations of love, this totally anthropomorphic vision of animal behavior. I saw this list online — you know those links at the bottom of news sites? “10 Things You Have to Do Before You Get Old,” or “10 Actresses Who Got Ugly...”

Yeah, of course, the “Around the Web” box. One of the few dependable revenue sources for a lot of media websites.

They’re everywhere! And “11 Animals That Mate For Life” was one of those. So there was a natural affinity with the email project.

In my exhibition “Bad Dad” [at Metro Pictures, in New York] animals played a somewhat different role, though here, too, it was tied into digital media. That series is very much about abuses of power, about injustice, frustration, powerlessness. I had been compiling different images that made me feel like that, and some of them were YouTube videos of animals being eaten by other animals.

I would always identify with the victim. Why? I suspect it wasn’t so different from the email project: ultimately the emotional reaction was always also about my feelings as a citizen, about my reactions to institutions, to any kind of structure that represented authority. And how it brings you back to your childhood. We feel like children when we are in contact with politics. You remember that feeling: you were a child, you were flooded with a sense of injustice, but you couldn’t do anything. That’s the feeling I think we all have right now.

You are currently preparing the biggest exhibition of your life, at the Palais de Tokyo in your hometown, and the show will have another kind of superstructure: it’s governed by the days of the week.

I have been working up to this show for a year, and already, when I was making the works in “Bad Dad,” I was thinking about the Palais de Tokyo. The emails too. Both of them for me are associated with Wednesday — which is the day I associate with political and social life.

Monday is probably my favorite day of the week. For many people it’s a day of melancholy, but not for me. As a child I would often not go to school — my mother wasn’t very strict, and she hated school herself. I wasn’t raised with the idea that school was mandatory. And I probably built my culture of escaping from that. For me Monday is about escaping duty. Have you read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man?

Not since college, but yes.

I read it last year, after my show in Rome, and that book is so much about Monday. One of the teachers says that since Saturday and Sunday are free days, you “might be inclined to think that Monday is a free day also. Beware of making that mistake.” Monday is about a state of melancholy, a need to turn inward.

Weeks, unlike days and months and years, have no astronomical referent. They’re human inventions. And the days of the week, in the show, are at once a social structure, but also quite individual too.

Exactly. The days of the week, for all of us, are like that: where your social duties interact with your personal rhythm. What is more personal than your schedule? Nothing. What you do with your time is the most intimate thing.

The days of the week offer the ideal structure for me because they embody this problem of the specific and the general that runs through so much of my work. The superstructure, but also the artificiality of the superstructure. The seven-day week is a system with mythological origins which got imposed on the rest of the world, often brutally. Days were numbered very differently in different parts of the globe. Then it became the day you go to church, the day you start working...

And yet, the system has become so familiar to us because of its repetition. Everything that repeats creates a dependency for it, even if it’s something bad.

These systems of knowledge can be imposed from above, imposed violently even, and yet from below they can be transformed, be personalized...

If you always see someone you love on Friday, or if you love to swim and you always swim on Thursday, you cherish that day. The days of the week are appropriated into your own system of emotions and experiences.

And then also in the digital sphere, the days of the week have become this new common field. We were talking about loneliness, but there is also, online, a kind of herd instinct: a desire to live the same experience at the same moment. So now we have Throwback Thursday, the hashtag #tbt. A day dedicated to memory, to your past life. Or Workout Wednesday, a day for health.

Instagram hashtags and memes make heavy use of the days of the week. Which makes a sort of sense, since the more time we spend looking at screens, the more we lose our pre-digital understanding of time. When the moon rises, when it’s going to be dark, the seasons: we used to notice these much more. Now we find out what time it is on our phones. I haven’t had a watch since I got an iPhone. It’s the phone that dictates the rhythm of the day and the week, and destroys the rhythm too: the phone erases the distinction between work time and free time, all the way into the bathroom, into your bed.

This, I think, created a fetishization of categories and hashtags that have become more like dispositions, or tempers. Thursday doesn’t mean Thursday anymore, it means memory. Saturday doesn’t mean Saturday anymore, it means going outside your boundaries. The days of the week became moods. They became worlds of signification within a shared digital society.

But the show itself does not change according to the day of the week, right?

I initially thought about doing that, but it’s too complicated. I wanted to change the schedule of the Palais de Tokyo, but it wasn’t possible. You can’t change when employees work — asking this was the ultimate taboo. The heart of the museum is the schedule.

You were mentioning your iPhone, and it features in one of the most enduring shots in Grosse Fatigue: the little frog that sits on the Apple touchscreen. That shot is so much more than an easy opposition of biology and technology; it’s this moment when the anthropological impulse marries the digital impulse, and you feel they’re not so different after all. Has putting together the Palais de Tokyo show clarified what holds those two things together?

Somewhat, yes. I’m always surprised when people use the world “technology” when we talk about digital culture. We’re rarely talking about hardware, we’re talking about human beings, politics, society. For me, the digital world doesn’t exist as something separate from the real world. It’s just a reflection; it’s still made by man.

There has been no rupture. We’re not living in a completely new era. As a matter of fact, the web and social media have allowed extremely regressive ways of thinking to emerge, both in America and France. That should be enough to prove that there has been no revolution. Or that the revolution is still to come, I don’t know. Digital life is not a new life; digital culture is just a window into people. It’s like a giant anthropological collection of our interior lives.