Scandal Sheet

by Suzy Hansen

Demonstrators outside the newsroom of Cumhuriyet, in Istanbul. 2016. Photo: Ozan Kose.

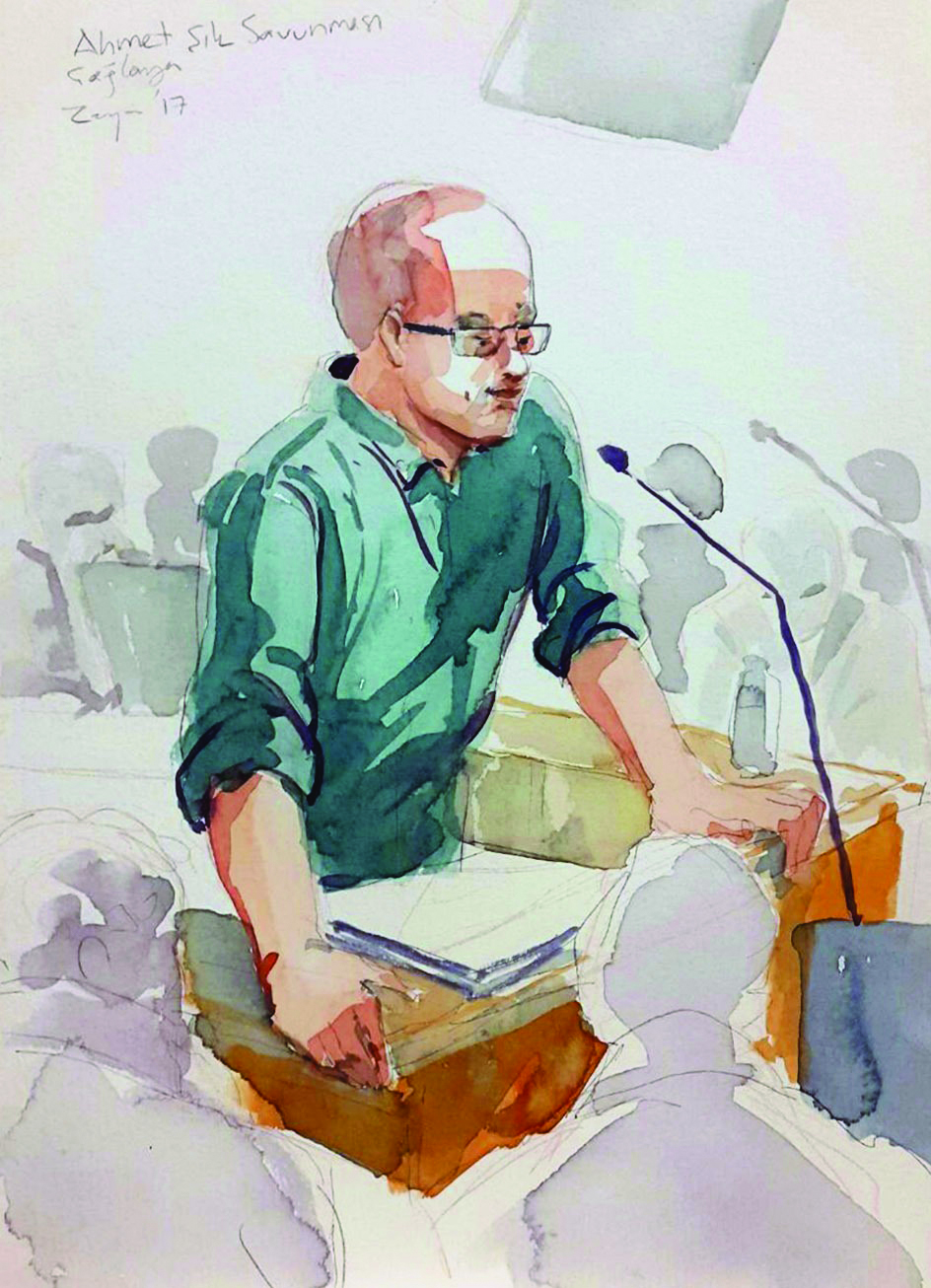

On July 24, Ahmet Şık, the most prominent investigative journalist at the Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet, stood in an Istanbul courtroom and mounted his defense. He had been charged with being a member of a terrorist organization — one of the most common and baseless indictments in Turkey today — and had already spent half a year in jail. His speech was less a legal defense than a journalistic tour de force, and one of the most potent analyses I’ve ever heard of what the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has become.

“Criminalization of journalistic activities is a common feature of totalitarian regimes,” Şık proclaimed to the court, and Turkey does it with particular gusto. More journalists are in prison in this country than anywhere else on earth, and the authorities have taken an especially tough line on the secular Cumhuriyet, Turkey’s oldest independent newspaper, whose title means “Republic” in Turkish. Its former editor, Can Dündar, was sent to jail in 2016 after the paper published a bombshell story that proved Turkey was providing weapons to Syrian jihadists (he is now exiled in Germany). This winter, Şık was arrested along with more than a dozen of his colleagues, including the new editor-in-chief, the books editor, columnists, and cartoonists. Despite the persecution, as well as falling circulation and advertising revenues, Cumhuriyet has kept up its tough reporting, as Şık insisted to the court: “Today, I am practicing journalism depending on the power of the truth, not depending on the power of the government or other power centers as it is broadly practiced in Turkey.... And journalism cannot be practiced by toeing the line.” His cross-examination also seemed to focus less on the things Şık was accused of than on journalism itself. “Does journalism have unlimited freedom?” the prosecutor asked. “I am tired of explaining freedom of expression to the judiciary,” Şık sighed.

Turkey has always had a particular problem with free speech, one that I found bewildering when I first moved here in 2007, a year after Orhan Pamuk, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist, had been put on trial for his words. Istanbul in those days topped all the glossies’ travel lists and was named European Capital of Culture, and Turkey then seemed to offer a kind of model for the Arab Middle East. Erdoğan led an Islamic conservative party that worried the old Kemalist elite, but he soothed some concerns by speaking frequently of freedom, human rights, democracy, and free markets. New newspapers were opening, and taboos like the Armenian genocide and the war against the Kurds were discussed openly for the first time.

The freedom of that brief period made the substantial number of journalists in jail — often in the hundreds — all the more bizarre. But putting journalists on trial has long been the Turkish state’s reflex against dissent. In the first years of the republic, Atatürk had the impossible task of forging a country and an identity out of a hodgepodge of ethnicities and religions; the state was the citizens’ dream, and anyone who threatened it, even with words, would have to be eliminated. Turkey would endure four military coups before an unsuccessful fifth attempted in 2016, and after each of them communists, leftists, Kurds, Islamists, nationalists, and others were immediately persecuted; newspapers shut down; cartoonists denounced.

By the turn of the millennium, when Turkey was knocking at the door of the EU, Erdoğan and his men were promising that everything associated with that repressive, coup-staging Kemalist state would have to go. The year I moved here, for example, prosecutors in the so-called Ergenekon trial alleged that a loosely connected group of hardcore secularist-nationalists was not only undertaking a coup, but had also assassinated the Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, executed thousands of Kurds, planned to murder Orhan Pamuk, and was arranging countless other dirty deeds. The accused members of this supposed Kemalist mafia included not only military officers who wanted to protect the secular character of the Turkish state, but, over time, academics, politicians, and many prominent journalists, too. (Ahmet Şık was one of them.) Even some of Erdoğan’s liberal and leftist challengers initially cheered the trial, which was seen as addressing taboos and redressing past crimes of the state.

Eventually, the Ergenekon trial and others like it would be revealed as pretexts to destroy the opposition. But what was curious to me, in those first years in Istanbul, was that many Turks and Kurds actually did hold journalists as responsible for historic state crimes as they did politicians. I heard it from Kurdish and leftist corners and from Islamists too: they remembered when mainstream newspapers pushed a strong, nationalistic state line, and even seemed to celebrate violence against minorities in Turkey. I am not suggesting that these critics wanted journalists to go to jail. But there was a sense that some newspapers seemed to be the state, and so it didn’t surprise many Turks that journalists might also collude with pro-state thugs. In a strange way, the long-held state view of journalists as threats had been deeply internalized: regardless of whether a journalist was pro-state or anti-state, they were not independent operators but ideologues who took sides.

It’s this complicated history of the role of journalism in politics that allows so many Turks — this time mostly supporters of Erdoğan — to shrug their shoulders at the imprisonment of journalists, especially of someone like Ahmet Şık. Now the Turkish state is again pursuing anyone who threatens it, but by 2017, the Turkish state is mainly the president himself. The idea that Şık was aligned with the “Fethullah Gülen Terrorist Organization,” as state media now call the movement allegedly behind last year’s coup attempt, is an absurdity; Şık was, in fact, one of the movement’s greatest critics. But that was never the reason he and his colleagues at Cumhuriyet were arrested; they were arrested because they were questioning the Erdogan government’s official line on what happened the night of the attempted coup. This very questioning, in the eyes of many Turks, was seen as support for the putschists — or, at the very least, antagonism of a government and a country facing grave threats. In the Turkish view, after all, a journalist could very well be a co-conspirator, even a militant.

It raises the question of how a democracy could have ever developed out of such a history. Ideology — or “toeing the line,” as Şık said from the defendant’s box — is existential in this country. And journalism, a discipline that works only if its practitioners aspire to impartiality and justice, makes very little sense when adopting a specific ideology feels crucial to your survival. What is much more surprising than the fact that men like Ahmet Şık are in jail is that men like Ahmet Şık ever existed. He did not necessarily belong to the nationalist or the leftist camp, the Islamists or the Kemalists. He was simply against boundless, unchecked power, and he is now suffering at the hands of the most powerful government Turkey has ever seen. When you watch the trials of men like Ahmet Şık, you begin to feel that it is exactly these people, some of its best people, for whom Erdogan’s new Turkey will have the least mercy.