August 2017

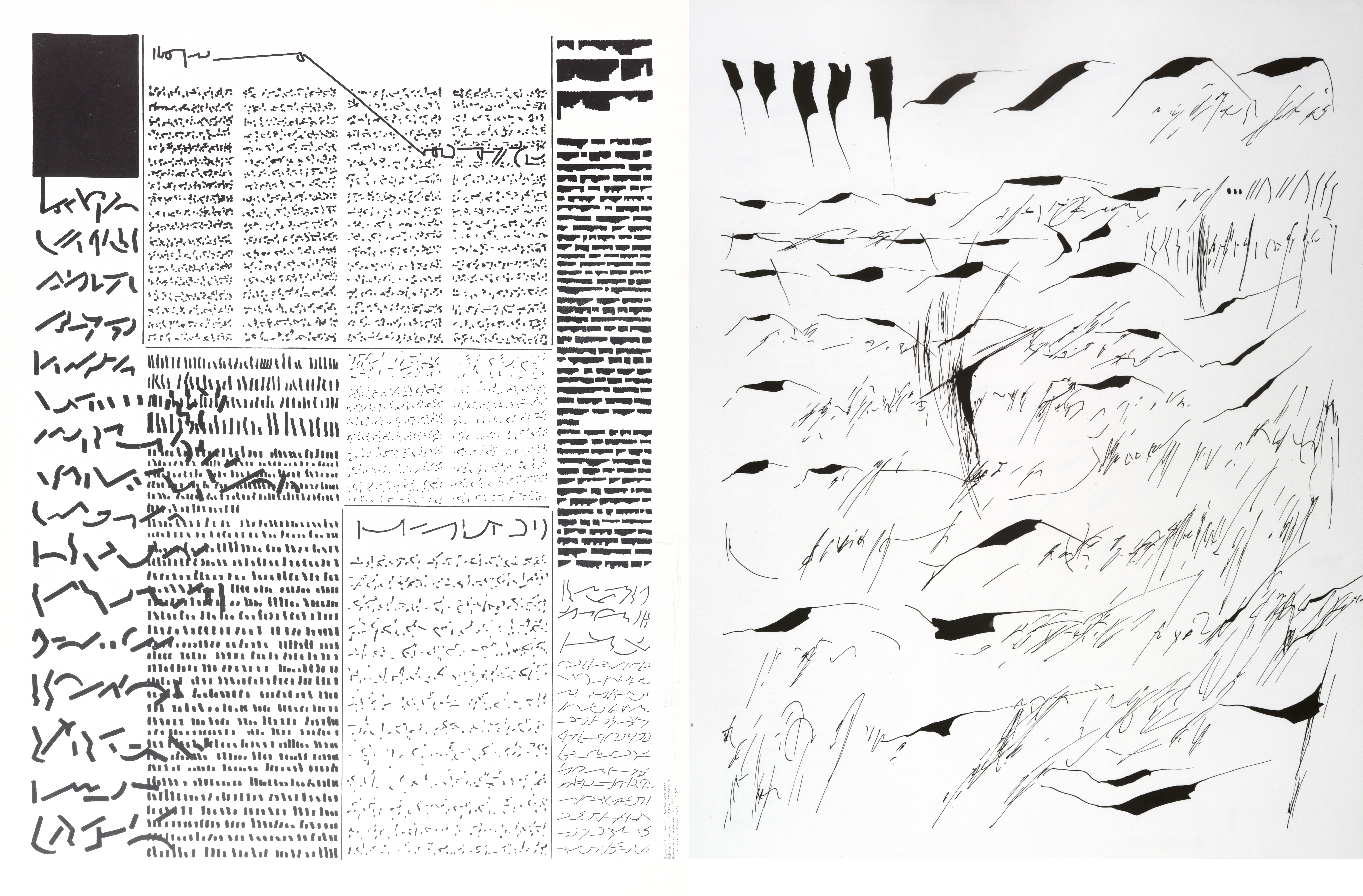

Left: Mirtha Dermisache. Diario No. 1, Año 1. 1972. Chinese ink and marker on paper. 18¼ × 14 in.

Right: Mirtha Dermisache. From Nueve Newsletters & Un Reportaje. 2003. Chinese ink on paper. 13¾ × 10¾ in. Courtesy MALBA, Buenos Aires.

Mirtha Dermisache

Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

Opens August 8

For 60 years now scholars of consciousness have been wrestling with a scrap of an argument left by Ludwig Wittgenstein in his posthumous papers: there can be no such thing, the gloomy Austrian said, as a private language. Whatever Descartes said about thought preceding all, meaning was rooted in society — and whatever your soul mumbled to you in the dark could only be a funhouse reflection of the words you heard outside. Analytic philosophers and linguists still can’t agree whether Wittgenstein is right, but one good argument against his claim lies in the intimate books and drawings of Mirtha Dermisache, one of the smartest and steadiest artists of postwar Argentina. In the 1960s, she began to write in abnormal scripts: sometimes a stuttering cursive, sometimes fat squiggles, concatenated arrowheads, or nearly Koranic calligraphy. By 1967 she’d published a book running to 500 pages, not one of which could be read. But she wasn’t writing nonsense: the upstrokes and hashes, scratched with the smallest of pen nibs, were semantic in their own way, words in a language more musical than Spanish or Sundanese.

Dermisache was born in Buenos Aires in 1940, and, although she frequently organized public workshops and collective actions, she did her best work in the silence of the scriptorium. “Well, no one here will understand what you are doing,” a fellow artist of the porteño avant-garde told her in 1969. “The only one who can understand it is Jorge Luis Borges, but Borges is blind, so you have no chance.” One of her illegible books, though, made it to Paris, where it fell into the hands of the literary theorist Roland Barthes — who was ecstatic, and who saw in her art the essence of writing. Like her, he too believed that the printed word was not a stable carrier of meaning, but an initial gesture that readers could interpret in a thousand different ways. You can think of Dermisache’s drawings and printed books as an artistic complement to Barthes’s philosophy, though she never divorced herself from meaning entirely. In the 1970s, just before a junta came to power in Argentina, Dermisache published a newspaper whose pages were filled with stubby upright strokes, EKG-like zigzags, and glyphs resembling shorthand. One column was blank: a column for the dead.

Art from Argentina has been getting a lot more international exposure lately, just as the country’s economy begins to stabilize. Art Basel will be popping in later this year for the first of its new Cities initiatives, and in Kassel this (northern) summer, Dermisache’s colleague Marta Minujín has reconstructed her giant Parthenon of Books, another work of art in which writing exceeds its role of communication. (In Even no. 3, Florencia Malbrán offers a survey of the art of Argentina's Kirchner era, and the debates over freedom of expression that accompanied it.) Dermisache’s own art has recently appeared at the Centre Pompidou and New York’s Drawing Center — often alongside European artists, such as Hanne Darboven, who also explored the limits of language. But there’s a particular Argentine resonance to her writing, whose pronunciation may be beyond our ken but whose meaning comes through clear. “I started writing and the result was something unreadable,” Dermisache explained in 2011, a year before she died. “Maybe the liberation of the sign takes place within culture and history, and not on their margins. In this sense my work is not behind the times at all.”

Yokohama Triennale

Yokohama Museum of Art and other locations

Opens August 4

Three years ago this significant Japanese exhibition bucked the curator-as-gatekeeper principle, and entrusted the show’s organization to the photographer Yasumasa Morimura. This time around a larger committee, including the artist Rirkrit Tiravanija and the philosopher Kiyokazu Washida, have been enumerating the triennial’s themes: something, it seems, about islands and archipelagos.

From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today

Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y.

Opens August 6

“I am a camera,” Christopher Isherwood’s detached motto, could also be the slogan for this anticipated show. In the 1960s, before smartphones and Adobe made photographic imagery commonplace, painters in America and Europe alike began to paint with the exactitude, but also the flatness, of light passing through a lens. More than six dozen works (not just big blow-up canvases, but also watercolors and other works on paper) make this a worthwhile stop, even if you have to sit in traffic on Route 27.

Kiki Smith/Thomas Cole

Thomas Cole National Historic Site, Catskill, N.Y.

Opens August 12

The father of American landscape painting might have been an aspirational Luddite, but that’s no matter — a kindred spirit is paying homage to his pastoral reverence this month. Smith is still best known for her early works concerned with the visceral body, but she, too, has taken a turn to the animalistic and spiritual later in her career; she'll be displaying her tapestries, bronzes, and exacting prints at Cole’s 200-year-old Catskills home.

Lone Wolf Recital Corps

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Opens August 19

The late saxophonist-sculptor Terry Adkins — who placed a central role in Okwui Enwezor’s 2015 Venice Biennale — crafted performances that concretized music and transmogrified art into sound. His multimedia troupe, the Lone Wolf Recital Corps, is being reunited for the first time since his passing, and will reprise former “recitals” with live instrumentation, video, and sculpture.

Picasso on the Beach

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

Opens August 26

In 1937, the same year he made Guernica, the big man painted a pair of beachgoers composed of volumetric fragments, lazing against a bitonal field of blue. It was the prize of Peggy Guggenheim’s home, and here on the lagoon you can see it alongside a host of drawings that reveal Picasso’s taste for sea and sun.

Mikala Dwyer

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Opens August 26

Grungy at first glance, Dwyer’s room-filling installations of sequined fabric, sheet metal, bunched plastic, and who knows what else have an obnubilated logic. Lately, however, Dwyer has been turning to occult-inspired geometric painting that cascades down the wall to the floor. Expect both here: she’s stuffing four whole galleries of the AGNSW’s Beaux-Arts home.

Back to Paradise

Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, Switzerland

Opens August 26

Halfway between Zurich and Basel lies one of the most reliably incisive museums in Switzerland, which this summer explores the political roots of Expressionist painting. Alongside Kirchner, Nolde, and other known quantities of prewar German art, the show also introduces Swiss Expressionists — such as Cuno Amiet, who made saturated canvases of mountains and heiresses and might be the Munch of the banking class.