Ordinary Beauty

by Emmett Rensin

The new US president plans, among other outrages, to kill the National Endowment for the Arts. Who would miss it most? A visit to central Iowa

Matthew Pratt. The American School. 1765. Oil on canvas. 36 × 50¼ in. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I.

Years ago, before I moved to this cornfield on the American prairie, I lived on the east coast and made government jazz. I can’t define that phrase precisely for you, but you begin to get it already. “Government jazz” was a joke between my housemate and me, a term for what we spent most of our time doing inside the overpriced corner of a former meatpacking warehouse masquerading as our apartment. Government jazz could be anything. You could play government jazz on the keyboard, of course, but you could draw government jazz too. You could write government jazz poems and sing government jazz songs, do a government jazz dance or cook government jazz food. Mainly, you could ramble until you were just talking government jazz for hours, ready for another Miller High Life, the government jazz of beers.

Government jazz wasn’t an insult, although it could be. (What are you playing? Man, that’s government jazz.) It was a request sometimes too. (Put on some government jazz while I’m cooking.) It was a compliment, and a mood, and a way to summarize your day. Government jazz meant ambient doing, mundane production, doodling and rambling and fucking around on a guitar. It was lame, most of the time, or just boring, but none of it was offensive. It was fine. We called it “government” jazz because there was something Great Society in its intentions, like muzak in the elevators of the bureaucracy, futzy liberal managers carrying out reforms that could never be the final answer, but which were nonetheless a very nice first step. The joke, understood between my housemate and me, was that no matter how much we rolled our eyes and made fun of one another, government jazz was necessary. It was the ground from which a good idea might burst forth at any time, and without which we never would have made anything at all.

On March 16, 2017, Donald Trump proposed a new federal budget that would, among other indignities, eliminate all funding for the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Donald Trump wants to kill our government jazz.

II.

I live in the center of the country now, on the eastern end of a midwestern state in which three-quarters of all arable land has been turned over to corn and soybean production, in a city where the “City” in the name is a misnomer, and it is from out here, far from Washington or Los Angeles or New York, that I am watching what we have preposterously chosen to call a “public debate” over the value of these national endowments. It would be stupefying if it were not so tedious — we are now enduring this debate for the sixth time in 50 years. Nowhere, in either the indictments or the apologetics, does any entrant appear to be especially familiar with the actual business of these agencies.

Not only the NEA and NEH’s opponents, but their defenders too, reckon with these agencies’ values in moral rather than economic terms. (The NEA and NEH each received $148 million in last year’s budget, totaling 0.006% of the federal outlay.) In one view, they are indulgent giveaways, exemplars of soft excess, charities funneling scarce resources into luxurious New York art projects (most of them blasphemous or explicit liberal agitprop) and disrupting the “voluntary market” of creative commodities. They are symbols of a wasteful state, beloved only by the out-of-touch, and must be obliterated as a statement of high moral (and financial) principle. In the opposing view, meanwhile, the endowments are among our most precious institutions, the keepers of our cultural fabric without which it would not be worth having a society at all, really, since no child would ever again know the joy of a painting or a music lesson or a PBS television show. In both cases, the usefulness of the endowments to the greater society is central: either they are indicative of every ill brought on by the post-New Deal order, or they are the best bargain we’ve ever had, sustaining a whole nation at the cost of a small toy for the Pentagon. In both cases, what is at stake is not so much any particular bit of culture, but the State of Culture in America itself. I am exaggerating only slightly.

In Coralville, Iowa, a town just across a brown river from the city where I live, there’s a two-story brick schoolhouse, constructed in 1876, which suffered significant damages after the river flooded a few years ago. (I am telling you this because it is a typical case of what the endowments involve themselves in, not an extraordinary one. We will return to the national debate in a moment.) Shortly thereafter, the school received part of a $116,000 grant from the NEH, given out to seven sites along the river, and the school reopened to the public. I’ve been there. It’s lovely inside, with dark lacquered wood and two-tone blue-green walls. “The brick building boasted native limestone foundations and cast iron star clamps,” the Johnson County Historical Society brags on its website.

At the University of Iowa, one can find the Division of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, which offers one of only a handful of MFA degrees in literary translation available in the United States. Only 3% of all books published in the US are works of translation; there’s not much of a market for the work that our translation grads do. The NEA, though, offers American translators an annual grant of up to $25,000 — an income that is, at least, above the poverty line. The next largest grant, from the nonprofit PEN Center, is for $5,000.

Or else, in the town of Coon Rapids, Iowa (pop. 1,305), there is a farm which Nikita Khrushchev visited in 1959. The NEA funded a three-day conference in Des Moines and Coon Rapids, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the visit. (An original play based on Khrushchev’s friendship with an Iowa corn salesman named Roswell Garst was commissioned for the occasion. I have not seen it, but I’d like to.) In Clinton, Iowa, a former lumber boomtown, you can attend the Clinton Book Festival, featuring “food, music, and programs for all ages,” made possible by a $3,000 grant from the NEH’s Iowa arm. In Davenport, Iowa, public funding has enabled the preservation of the first railroad bridge to cross the Mississippi, plus an archaeological dig alongside. “More than eight thousand cyclists who come to Iowa every year for the Des Moines Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Race Across Iowa can also learn about Iowa’s archaeological heritage sites and small towns across the state,” the NEH state talking points proclaim.

Perhaps the above will clarify the shape of culture across the United States, far more so than any statistical paean to “arts exposure,” or any tale of debauched performance artists burning tax dollars alongside photographs of the Pope. The NEA offsets premiums on insurance for museum loans, so artworks can travel. The NEH steadily digitizes hundred-year-old newspapers, in case some future scholar needs them. Sometimes, rarely, the endowments fund a future Pulitzer Prize winner. Sometimes, rarer still, the money finds a hidden Mozart in deep poverty. But these are the exceptions. Most of it is only fine, only nice to have, often boring, really, the mundane currents of a culture.

III.

When reactionaries talk about the NEA and NEH, they do not talk about schoolhouses or digital archives of old newspapers, or small grants for plays about Khrushchev on the prairie (although I wonder if they simply haven’t heard of that one yet). They talk, if they talk at all in the particular, about Piss Christ.

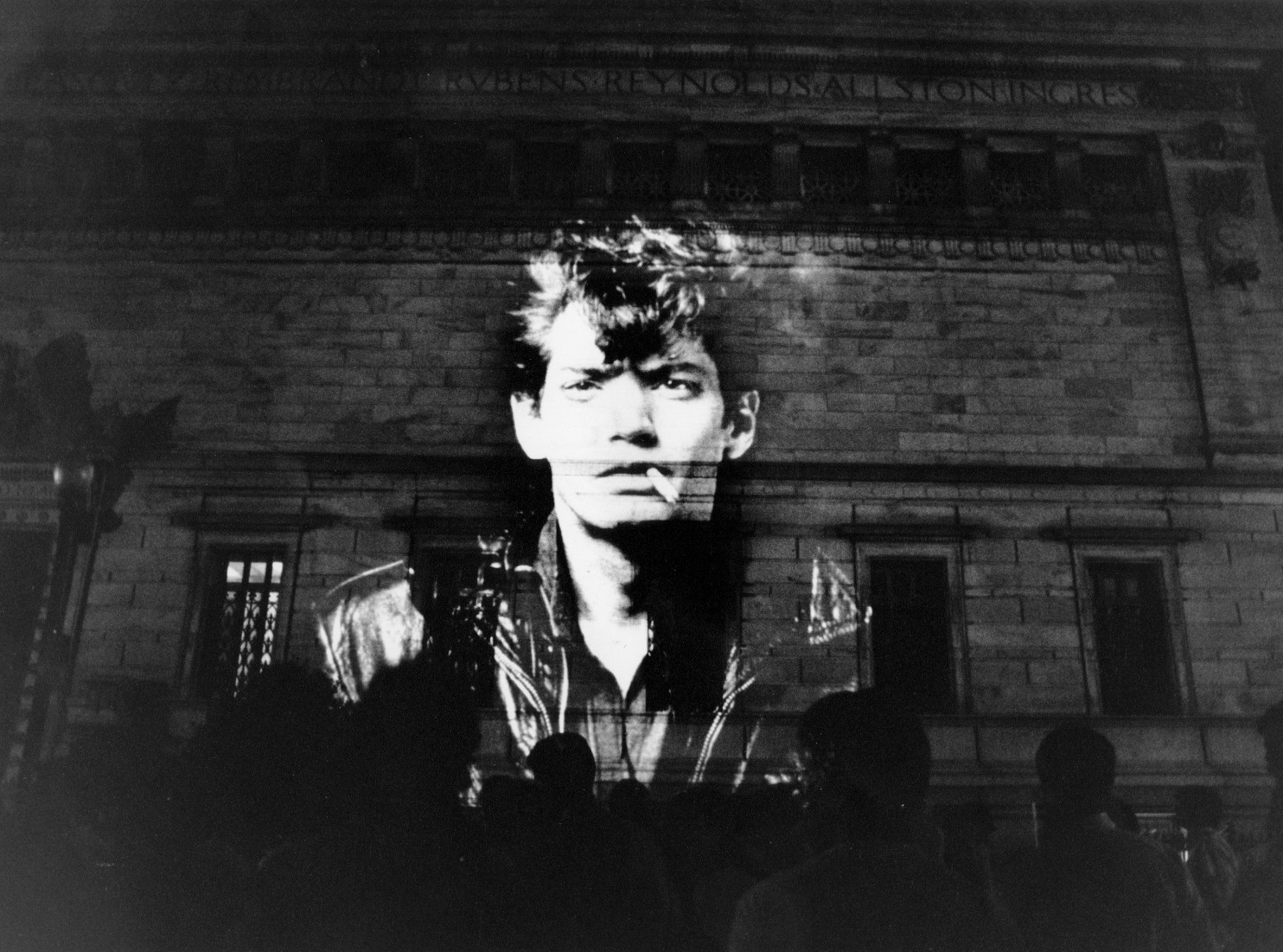

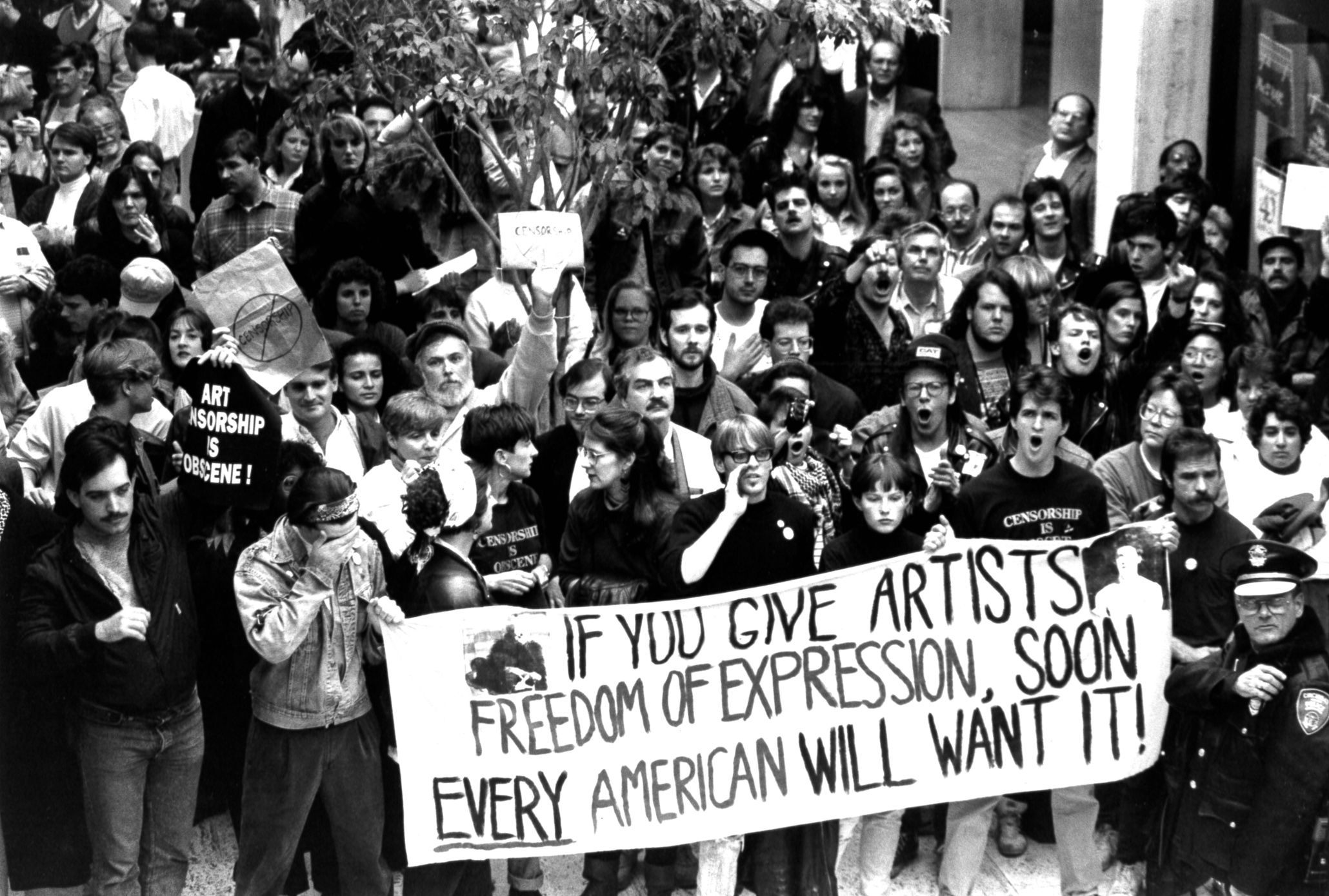

You already know the story of Piss Christ. In 1989, the artist Andres Serrano exhibited, at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, a photograph of what is almost certainly a crucifix, in what is probably a glass, submerged in what may or may not be Serrano’s urine. The American Family Association caught wind of this blasphemy, and after the evangelical Pats — Robertson and Buchanan — joined him, the Republican senator Jesse Helms began demanding that the NEA be punished as a consequence. The endowment’s connection to the affair, as far as it went, was a partial sponsorship of the Southeastern Center’s award in the visual arts. Serrano, who had already shown Piss Christ in a commercial New York gallery, was one of several winners that year.

You also know the story of Ronald Reagan’s failed push to kill the NEA because it went “too far” (in what?), and you know the story of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington cancelling a Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition, and you know the story of Newt Gingrich demanding the “elitist” NEA and NEH be defunded entirely (he managed to end individual grants to artists) and you know the story of a 2009 conference call, when the NEA’s communications director requested more funding for art promoting “areas of service” (like child nutrition and trailer repair), which Andrew Breitbart publicly interpreted as a call for pro-Obama agitprop, and really, if you know none of these stories in particular then you still know them all in general because the story is the same every time. The story is about government agencies that are not only wasteful but insidious, the prime drivers of liberal politics and New York values and anti-Christian bigotry masquerading as inoffensive arts bureaucracies. Get rid of these, the story goes, and the tide of the culture war can finally turn. The NEA, an influential report from the conservative Heritage Foundation informs us, exists to “subsidize the well-to-do,” “promote politically correct art,” and “underwrite pornography.” “The NEA lowers the quality of American art,” they tell us.

That story has nothing to do, of course, with the German American Heritage Center in Davenport, which received a $5,000 NEH grant to “develop a long-range plan” for the maintenance of its letters, photographs, artifacts, and documents from two centuries of German immigrants. It has nothing to do with Jesup, Iowa (pop. 2,500), where an NEA grant treated residents to their first string quartet concert in 1992. It has nothing to do with the 80 school teachers who spent a week studying Frank Lloyd Wright in Mason City with the help of a $180,000 NEH grant, the single largest given to Iowa by the endowment between 2008 and 2012.

But these have little to do, either, with the claim that the national endowments represent the central “value” of arts in the United States, as the National Council of Nonprofits suggested this year. The endowments, whatever their business, do not fulfill the “critical” function of “promoting the arts” in a country without a ministry of culture, as the outgoing Met director Thomas P. Campbell recently alleged in the New York Times, and the fight over them does not constitute, as he says, an “assault on artistic activity.” While defenders of the endowments often note in passing the laudable work of offsetting insurance premiums and keeping local museums afloat, they are disposed, in moments of threat, to launch into full hyperbole. The NEA and NEH become the defenders of American culture, the only way that “arts exposure” can come to the American poor, the central pillar of a proud (and largely blue) America that chooses not to be illiterate or stupid. “To someone such as me,” former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee wrote in an aisle-crossing defense of the agencies this spring, “[someone] for whom an early interest in music and the arts became a lifeline to an education and academic success — this money is not expendable...it is essential.” He may be overestimating how essential many Americans find the success of Mike Huckabee.

The implication, as the stakes are inflated and inflated, is that in the absence of the endowments, culture would simply cease to exist in this country, or become a domain more or less inaccessible to anyone not born into luxury. (As it happens, this is pretty much the situation already.) In order to be worth saving at all, the apologists imply, the whole culture must depend on them. It becomes a preposterous recitation, accompanied in almost all cases by an (entirely fabricated) reminder that even Winston Churchill admonished a request to cut arts funding during World War II by asking, “Then what are we fighting for?” But nobody has ever stood in the A-frame home of the Museum of Danish America in Elk Horn, Iowa — recipient of a $2,000 grant to offset storage costs for their photography collection — and thought “We won the war for this, thank God!”

(It is well known, in any case, that an American seeking government assistance for a truly radical artistic enterprise is better off appealing to the CIA. Among federal patrons of the avant-garde, it is the truly essential agency, counting the Kenyon Review, Paris Review, abstract expressionism, and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop among its success stories.)

But I am perhaps being unfair when I accuse our national liberals of inflating the stakes of the endowments beyond all reasonable measure. At the slightest pushback, they retreat, always, to the reminder that the NEA and NEH cost a tiny percentage of the federal budget, so little that completely eliminating them would make no discernable difference to national finances. (Culinary metaphors are popular here: if you wanted a slice of apple pie equivalent to the NEA’s share of the budget....) And this, indeed, is where the NEA and NEH’s defenders and detractors agree. All of this has to do with money, with the commodification of art and its contribution to GDP. The question is only whether or not the art we’re buying is any good. Thus, for the reactionaries, the art must become blasphemy, and for the liberals, it must become excellent enough to constitute a bargain. Otherwise, why so much fuss over taste?

IV.

I want the National Endowment for the Arts. I want the National Endowment for the Humanities. I want them and I want institutions bigger and stronger and more powerful than them. But I do not want to defend them on the terms that we are given even by their more steadfast national advocates.

What is so infuriating about this interminable debate is how completely captured it has become by the superlative — which is to say, how completely it has embraced the terms laid out by reactionaries. The Gingriches and Breitbarts and Trumps insist that these endowments are vested with a limitless and wasteful power, that they are a proxy for the whole godless New York culture apparatus, working their dark snobbery into the hearts of an easily corrupted people...to which the liberal apologists reply with their consent. Yes, they say, the endowments do determine the course of art in the United States. But it’s good, actually. All of this is done with the best of intentions, but ultimately they fight the battle on a field chosen by the enemy, forcing apologists to defend a silly and counterproductive position that is exposed by even the most cursory examination to be a farce. The NEA and NEH are the pinnacle enablers of our culture, and you can’t believe the deal we’re getting! This plays right into the commodifiers’ hands. It suggests that the NEA and the NEH are only good because they produce superlative culture, and even then are only defensible because they’re cheap.

I want the National Endowments for the Arts and for the Humanities not for their excellence, but for their mundanity. I want them because they represent, in small ways, the constant churning baseline of American culture. I want them because they are government jazz. The danger in the apologist’s distortion is that they turn the endowments into something that must exist for greatness, which must produce greatness in order to earn their keep — and, in that way, they slot into the exhausting tendency in current American discourse to blow up every cultural artifact to life-or-death importance. But this, at bottom, is the logic of austerity. This is the trap that will eventually doom the endowments and every other small pleasure that we’ve got.

American culture does not ride on the NEA and NEH, but it doesn’t matter. The endowments will produce greatness here and there, but they shouldn’t have to in order to survive. The arts and humanities should be — will be — boring and silly sometimes. What else do we expect? I am blessed to experience this culture all the time, to see paintings and hear music and attend readings, most of which aren’t very good or very interesting, most of which do not purport to be The Best or purport that my exposure to them might make me or any other audience member The Best in due time. To be bored out of your mind in a dim-lit cultural heritage site in the middle of a cornfield, browsing the gift shop, and tapping your foot to the muzak on the radio, humming along to some good old government jazz: this is the true blessing. We didn’t win the war for the ordinary arts and the humanities, but they do not need a war to justify them either. They are the commonplace of a generous and kind society. That’s all.