Within a Budding Grove

by Emil Leth Meilvang

These days the art world is infatuated with all things biological — conscious cells, mutating organisms, blooming gardens. Two exhibitions see Paris go green, but does our taste for science suggest a doubt of art?

Two photographs of plants by Karl Blossfeldt, from the series Material Forms in Nature. 1928. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

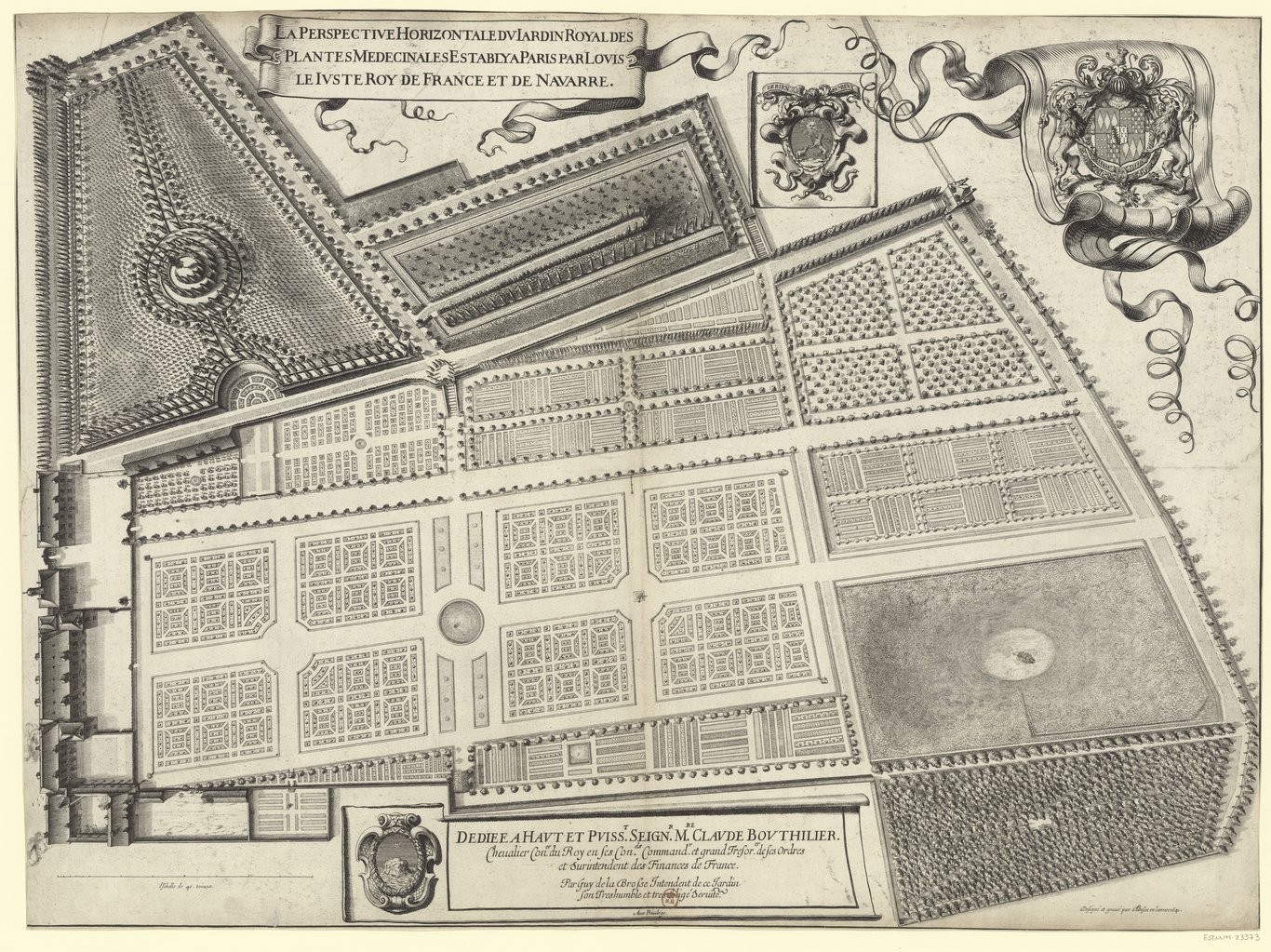

The Jardin des Plantes, Paris’s botanical garden, lies in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, a stone’s throw from the Seine and hard by Austerlitz train station and France’s oldest mosque. It’s been there since 1626 — back then it was called the Jardin du Roi, and it was a few decades before the king opened it to the public — and its wrought-iron greenhouses, its zoomorphic stone fountains, and its alleys of canopied trees reflect centuries’ worth of efforts to discipline the natural world for human appreciation. One of my favorite spots in the Jardin des Plantes is the Alpine garden, a sunken Swiss hideout that breaks the gardens’ French regimentation. It dates to 1640, and a few months ago I was sluggishly drifting through it, amid the thick Paris summer heat. There, enmeshed in the vegetal vibrancy that the life sciences seek to penetrate, I overheard a quip from a Frenchman walking by. “It’s a foolish idea,” he said — and it was more natural in his language — “to cultivate what we take as the image of our own cultivation.”

It was a somewhat circular aphorism, sure. But the man was onto something: gardens are a nexus of natural and cultural history, of botany and artistic mimesis. The massive, immensely articulate exhibition “Jardins,” on view this summer at the Grand Palais, strolled through the history of gardens from the early Renaissance to the present day, via paintings, drawings, and photographs, but also botanical cuttings, landscapers’ plans, and even a range of eccentric garden instruments. It was a blockbuster that examined man’s attempts to tame nature, and it was one of two shows in Paris this season that made me reassess the overcooked marriage of “art” and “science” lately in vogue in the art world; the other, “Le rêve des formes,” transformed the Palais de Tokyo into a laboratory of art, biology, and technology. Both shows boasted extensive artist lists, and both were created in intimate dialogue with practicing scientists. And both had ambitious, bordering on impossible, aspirations: “Jardins” told the story of man’s attempt at framing nature, while “Le rêve des formes” proposed morphology—that is, the creation of forms—as the hinge connecting art and science. Seeing them together offered a pertinent opportunity to interrogate the art world’s ongoing fascination with the life sciences. Not only that: they took the lopsided rules of engagement by which “art” looks as “science” as their very themes.

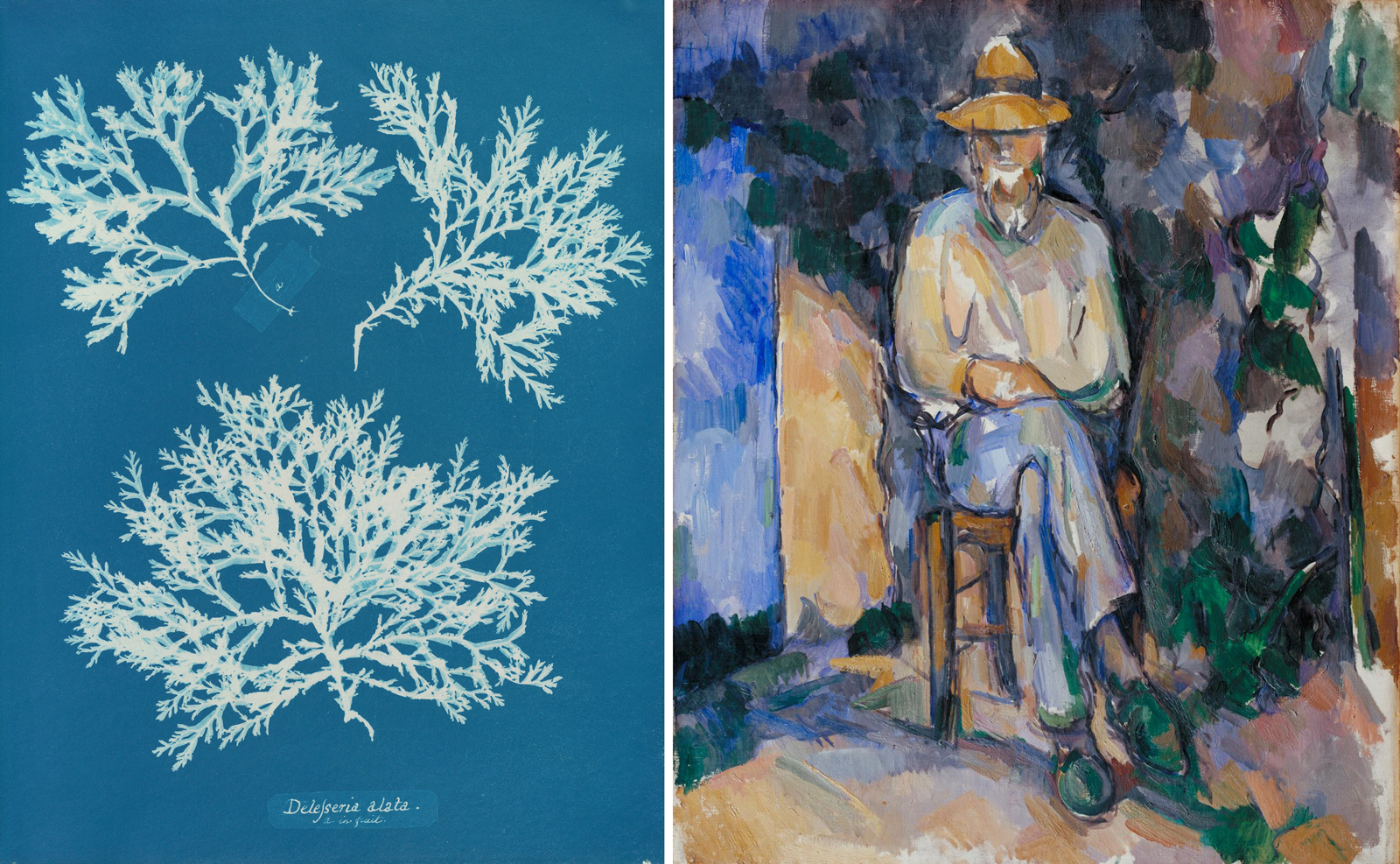

Laurent Le Bon, the director of Paris’s Musée Picasso and the curator of “Jardins,” envisions a time when the boundaries that now separate art and science were more porous, if not wholly superficial — and his associative, self-conscious curating mapped out a nonchronological itinerary that wove together objective and subjective views of gardens since the Renaissance. On view were staggeringly beautiful herbariums (including the personal belongings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Paul Klee), carefully detailed botanical studies, maps, and clips from the cinema. Not to mention photography and painting: the walls were radiant with canonical works by Dürer, Delacroix, Monet, Redon, and Picasso, with brief dashes to contemporary figures such as Gerhard Richter, Jean-Michel Othoniel, or Wolfgang Tillmans. Although, or because, the show followed such a well-trod, boys’ school path through the garden of European art history — not much “cultivation” here — Le Bon’s conceptual frame was supplied principally by a selection of suggestive quasi-scientific pieces. Among them were the ocean-blue algae cyanotypes from 1845 by Anna Atkins, a pioneer of scientific visualization who is considered the world’s first female photographer, although no camera was needed to create her ghostly impressions of Polysiphonia fastigiata or Cutleria multifida. There were early experiments in time-lapse cinema by Jean Comandon, a microbiologist whose lush, black-and-white films documented heliotropic movement of flowers, as well as delicate glass models of plants, presented as specific botanical specimens, blown by the artists Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka in turn-of-the-century Dresden (a rare loan from Harvard’s natural history museum).

The exhibition’s motion towards interdisciplinary understanding was crystallized in a section devoted to plant studies, done by both artists and scientists. Drawings, cuttings, and herbariums were displayed amid floral photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch, August Sander, and Karl Blossfeldt, all of which evoked the 19th-century model of the scientific atlas: a large collection of objects or illustrations meticulously indexing a specific area of knowledge. Modernist form punctured this scientific paradigm, however, via Man Ray’s flickering close-up of a flower that only mimics botanical photography, filtering the scientific paradigm through surrealist models of desire. In Ray’s photographic surrealism, the petals of the wide-open magnolia flower are brittle, glistering, and obscene. He exposes the specimen of the herbarium as contigent and highly fetishized. (The philosopher Emanuele Coccia unpacks this point in his new book La vie des plantes: it is an ontologically distinctive trait of plants that they can be cut up without ceasing to exist.) Our desire to look at plants and flowers is intimately tied to their supposed fragility, and Man Ray’s photograph implies that this only intensifies our urge to crush them.

Besides such brief glimpses of transgression, there was an overall tranquillity to “Jardins,” even in the low-ceilinged galleries of the Grand Palais. The number of pieces was staggering but not indigestible. The range of representational formats was astounding but visually coherent. The emphasis was on historical thinking, and on the differing speeds of cultural history and natural history. Eugène Atget’s photographs from the 1920s of an abandoned, worn-down Parc des Sceaux, in which overgrown plants recolonized manmade alleys and statues, attested to this double time signature. So did Paul Cézanne’s late portrait Le Jardinier Vallier (1906), in which a gardener almost seems to dissolve into splotches of vegetation, his feet stained with the green of the nature.

Right: Paul Cézanne. Le Jardinier Vallier. 1906. Oil on canvas. Tate Modern, London.

One realizes from Le Bon’s exhibition that what makes the garden so distinctive, both culturally and scientifically, isn’t that it offers a pause from urban life. It’s rather that its vegetal microcosm presents itself as a virtual window, making hitherto impossible comparisons possible. Superimposing diverse biotopes in a single plot — like at the Jardin des Plantes, where it’s just a short stroll from the Swiss confection of the Alpine gardens to showcases of Mexican and Australian flora — the garden becomes a space of virtuality itself. The botanist and the artist, the scientist and the cultural critic all entertain this superimposition. Nowhere was this more delicately laid out in “Jardins” than in a little watercolour by Paul Klee, Garten zur roten Sonnenblume (1924), in which slender, halfway articulated lines momentarily punctuate the flat, two-dimensional image of the garden like uncontrollable weeds in a manicured allotment. The geometric vegetation — colored squares in Klee’s spatial decomposition — is fleetingly injected with botanical potentiality through the tiniest of linear gestures. Klee seems to foreshadow Michel Foucault’s dictum that “the garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world.” In that way, the garden is not so different from the museum: both aspire to be multidisciplinary, multisensorial kingdoms of art, architecture, botany, and zoology. Think of them as self-enclosed pockets of knowledge, mimesis, and pleasure, which simultaneously imitate, enlarge, shrink, and shut off the world outside.

In stark opposition to the deeply historical viewpoint of “Jardins,” “Le rêve des formes” at the Palais de Tokyo spoke only in the present tense. Mounted on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Le Fresnoy, an art school in northern France that specializes in moving images, the curators Alain Fleischer and Claire Moulène turned the lower halls of Paris’s massive Kunsthalle into a testing ground for an intermarriage of science and art, with work by several talented contemporary figures, such as Katja Novitskova, Anicka Yi, Dora Budor, and Jean-Luc Moulène, presented side-by-side with the research of theoretical physicists and biologists. The exhibition didn’t shy away from big statements: its wall texts brimmed with elaborate explications of the potential kinship of diverse intellectual endeavors, and, from the title on, it offered the notion of form as a concept that could serve to reconcile artistic and scientific production.

These artists have a shared preoccupation not just with form, but with the notion of form as a pattern that bursts right out of matter itself. Whether in Julian Charrière’s photographs transformed by nuclear radiation, or in artist-researcher Olivier Perriquet’s livestream of beluga whales, the recurring idea in “Le rêve des formes” was that form can enunciate itself with no need of an artist. Of course, the idea that the form of an artwork can be self-generated, not sculpted by an overarching authorial genius, is not a new idea in the history of art. You could plot a path through the art of the last century from Hans Arp’s chance-based collages, their form determined by the physical properties of wind and paper; through the postminimal sculpture of Richard Serra and Robert Morris, who wanted materials to settle into their own natural shapes and configurations; to the open systems of this show’s éminence grise: Pierre Huyghe, the most important French contemporary artist of the last two decades, whose fish tanks and living ecosystems are a clear influence on the young artists here.

Nevertheless, in “Le rêve des formes” science sought to give new lease on life to such self-generating strategies. Especially successful in this regard was the installation Infragilis (2017), signed by Hicham Berrada (artist), Sylvain Courrech du Pont (morpho-geneticist) and Simon de Dreuille (architect). Coming into the main room of the exhibition, viewers were immediately confronted with an immense video projection of what initially seemed to be rolling dunes. The next room, however, revealed that the images originated from an aquarium in which the water slowly, continuously reshapes sand-like particles into new arrangements. Images from the aquarium were gradually added to the projection; the piece’s self-generating aesthetic illuminates the exchanges among matter, simulation, and entropy.

There was something inherently hopeful about “Le rêve des formes,” which seemed to think that by decorating art with the wonderful badge we call the sciences, art can automatically gain not just critical strength but political relevance. But let’s be honest: such exaltation ultimately reproduces the exact same distinctions that an exhibition like this one sets out to deflate. The direct integration of scientists in a museum can’t avert the fact that uncritical appraisal of biology, physics, and newer disciplines depends on a major cultural asymmetry. (After all, we in the art world can get away with a hazy understanding of gene splicing or geoengineering, but can you imagine how quickly our doors would slam shut if a scientist thought she could curate a biennial or rehang a collection?) “Le rêve des formes” surely wishes to puncture the monolithic distinctions between art and science, but to do so you need history — which potentially could reveal those two now homogenized categories as deeply contingent, even mutually inclusive. Instead the Palais de Tokyo’s show wholeheartedly put its chips on “interdisciplinary” practice as a good in itself. This is in many ways admirable. It might also be somewhat confined.

To cultivate what we take as the image of our own cultivation.... The quip that I overheard (and who knows if I even heard correctly) that sweltering day in the Jardins des Plantes reminded me that, for all the spiritual power we ascribe to art, humans tend to distribute even more spiritual authority to nature. Why do we still have this naïve belief, in this alleged era of the Anthropocene, that the natural world has its own special dynamism, removed somehow from the dynamism of human affairs? I can’t say for sure, but that assumption might be what ultimately binds together two exhibitions as different as “Le rêve des formes” and “Jardins.” What springs from their bristling vitality, and what might be an undercurrent in a whole range of contemporary ways of thinking that bridges art and the biological sciences, is the age-old quest for art to exist as a living entity. Sacred artists and secular artists, in medieval times and modern ones, have had that goal, and the young artists at the Palais de Tokyo, calling on geneticists and nanotechnologists, are not so different.

We say “interdisciplinary,” but there is a simpler word for the meeting of art and science: life. Biological time is linear, but human history is circular, and dialectic; to think meaningfully about the pair of art and science, you have to think historically too. That’s even more true now than it was two years ago, when the world’s leaders came to this city to sign a climate pact that the new American administration has already abrogated. Nothing in our radically ecologized present is outside of history, and a show that interpenetrates art and science can only be a show about life and the living.