The Four White Stitches

by Daniel Penny

“What’s that jacket, Margiela?” said Kanye, and a generation rushed to buy black clothes with the most discreet of labels. Two Parisian exhibitions pull back the curtain, very slightly, on a Belgian enigma

A cape coat from the autumn/winter 1991 collection of Maison Martin Margiela. Photo: Julien Vidal.

As the avant-garde of late 20th-century fashion nears retirement, museums around the world have begun paying homage to some of its most unruly figures. In the past few years, the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has canonized Alexander McQueen and Rei Kawakubo in solo shows, while Rick Owens just wrapped up a takeover of the Triennale di Milano. Now Belgian designer Martin Margiela is receiving similar treatment with two massive, simultaneous exhibitions in Paris: one at the Palais Galliera’s Museum of Fashion and the other at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Each exhibit comes with a monograph and merchandise, which seem to be available at every hip bookstore in Paris. Meanwhile, We Margiela, a new documentary by the designer’s recently deceased business partner, Jenny Meirens, is making the festival circuit. After a decade of waning relevance, Margiela appears to be back in the spotlight.

“Margiela Galliera: 1989–2009,” at the Palais Galliera, spans the length of the designer’s career and portrays Margiela as an iconoclast who turned the fashion industry inside out, demanding that his conceptual clothes “speak for themselves.” “Margiela, les années Hermès,” at the MAD (and seen last year at the ModeMuseum in Antwerp), focuses on the 12 seasons Margiela spent designing ready-to-wear for Hermès, a partnership that brought his experimental sensibility into dialogue with a more luxurious and subtle body of work. Margiela is reluctant to speak publicly about his process or offer interpretations of his clothes, so it is notable that both shows credit him as the artistic director. Given Margiela’s hand in the exhibits, visitors may be tempted to view them not just as an evaluation of the designer’s legacy, but as a kind of autobiography.

Martin Margiela was born in 1957 in Leuven, Belgium, a small city near Brussels. In 1980, he graduated with a degree in fashion from the Royal Academy of Antwerp, shortly before a group of classmates who would become known as the Antwerp Six. He soon made his creative home in Paris, working as an assistant designer for Jean Paul Gaultier from 1984 to 1987. The following year, Margiela and Meirens, a boutique owner and early adopter of progressive design in Belgium, formed Maison Martin Margiela and held their first show, a spring/summer collection they called “Défilé.”

“Défilé” is where “Margiela Galliera: 1989–2009” begins. A long runway of white cotton leads visitors through the entrance of the exhibit, marked by a curtain of ripped plastic, into a room of veiled mannequins dressed in basic, white cotton shifts from the show. Upon closer inspection, the shifts appear to have been darted, torn, and reconstructed. On the mannequins’ feet are Margiela’s iconic Tabi boots, inspired by the Japanese socks that separate the big toe from the rest. Here, the white runway has been soiled with what look like bloody footprints, which Margiela would produce by having his models dip their Tabi boots in red paint before walking.

“Défilé” not only introduced many of the design motifs Margiela would revisit in later collections, but it also established the enigmatic approach to branding that would define the rest of his career. Unlike his mentor, Gaultier, who embraced celebrity culture, Margiela refused to be interviewed or photographed, avoided taking bows after shows, and demanded that communication with his atelier be conducted via fax. Replies from the house were written in the first person plural to underscore the collective anonymity of the Margiela team, who wore a uniform of the traditional blouse blanche. Margiela’s stores and ateliers were not listed in the phone book, and their interiors were restricted to a neutral color palette, creating the uniform, blank canvas that has now become standard for high-end boutiques around the world.

In a 2017 interview with the New York Times, Meirens recounted how she and Margiela cultivated an aura of tantalizing anonymity in the months leading up to their debut. They hated the concept of “designer” clothes, and so they sewed a blank white label into every piece, with four white stitches exposed on unlined garments — a spectral authorial presence that would evolve into a subcultural sign of affinity and cachet. “When people come into a shop and see strong clothes with no name on them,” Meirens told the Times, “they are going to be more curious.”

Margiela’s refusal to play by the traditional rules of fashion extended beyond branding. He frequently employed women who were not professional models — who often appeared in masks, veils, or oversized wigs in order to maintain a focus on the clothes. Similarly, the house preferred far-flung, unglamorous venues for shows and eschewed the usual hierarchical seating chart, sometimes eliminating seating altogether. Margiela presented collections in disused theaters, an abandoned metro station, and a Salvation Army complete with marching band. In 1993, Margiela went a step further by making it impossible to see his whole spring/summer line at once — separating the collection by color and showing each half simultaneously at opposite ends of a cemetery. These events were more akin to Fluxus happenings of the 1960s or the New York loft performances of the 1970s than the highly prescribed rituals of fashion shows — they created radically new dynamics between performers and audiences that made everyone a participant.

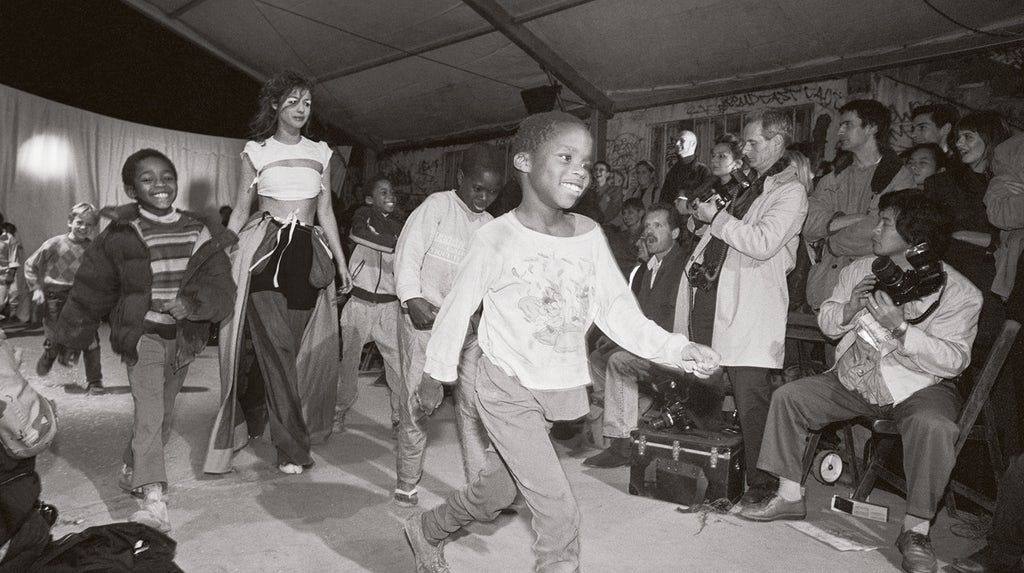

For his 1989 autumn/winter show, which would become Margiela’s most famous, he and Meirens chose a rundown playground on the outskirts of the 20th arrondissement, then still a poor neighborhood. Local children who used the playground were encouraged to participate in the show by making the invitations in art class and sitting with the guests alongside the dirt runway. A loop of footage in the exhibit shows the wild exuberance of the crowd as the collection reaches its crescendo, with children running among the models and hanging off their backs.

Both exhibits present Margiela’s early work as though it had been universally admired at the time. In fact, many viewers were hostile, including Laurence Benaïm, fashion critic for Le Monde, who described the playground setting as “miserablist scenography.” Today, fashion historians and designers regard it as a seminal event. “I was so struck by everything I was seeing that I started to cry,” Raf Simons would later tell an interviewer. “I walked out of it and I thought, ‘That’s what I’m going to do.’ That show is the reason I became a fashion designer.” Margiela sought an authentic engagement with the spaces and local communities he incorporated into his shows. In comparison, the outlandish venues used by contemporary designers, such as the dead-end street in Bushwick where Alexander Wang presented his spring/summer 2018 collection, seem like mere stunts.

Rejecting fashion’s constant search for novelty, Margiela established a set of themes and tropes, which he developed and revised from season to season. The first of these is a fondness for trompe-l’oeil clothes, makeup, and accessories, which runs throughout his oeuvre. The section of the Palais Galliera exhibit devoted to Margiela’s spring/summer 1996 collection most fully embodies his interest in optical illusions; silk dresses, printed with photographs of gowns and suits, almost resemble the tuxedo T-shirts favored by slacker prom dates. Strapped to the mannequins’ feet are stripped-down Tabis that consist of a black leather heel and clear packing tape, making the shoes practically invisible. In other collections, Margiela employed trompe-l’oeil makeup, such as fake tattoos or black circles around models’ eyes in the shape of Jackie O sunglasses, which added a dimension of surrealism to otherwise staid ensembles.

Margiela was similarly playful when it came to the scale and volume of his designs. Highlights include his autumn/winter 1994 collection, for which he scaled up doll clothes from the 1960s and 1970s. The effect is comical: massive buttons, oversized sleeves, and labels the size of postcards. For spring/summer 1998, Margiela created a line of 2D clothing that hangs perfectly flat, and which, through the ingenious use of zippers, can shrink and expand.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Margiela’s radical approach to fashion was his penchant for recycling. The garments in the brand’s “Artisanal” line are made of found materials, like Monoprix shopping bags, flea-market silk scarves, or fisherman waders painted white, but their construction is sophisticated and delicate. One handbag is made of a black motorcycle helmet and a leather strap. Old tulle ball gowns have been dyed black or bleached white, split down the center, and paired with distressed jeans. For Margiela’s spring/summer 1997 and autumn/winter 1997 collections, he transformed dressmaking materials — the brown linen of Stockman dummies, basting thread, and pattern paper — into tops that celebrate artisanship and undermine the notion of finish and perfection.

Not content to rummage through the discard bins of others, Margiela even cannibalized his own archive, reusing the red-splattered runway from his first show to make tops and shirts the following season. For his spring/summer 1999 collection, he rereleased select items from each of his previous seasons as a kind of “greatest hits” series. In an age that exalted glitz, Margiela’s use of throwaway materials was a profound aesthetic and philosophical departure. Auguring the era of sustainable design, he questioned the economic necessity of making new clothes, given the surfeit of old garments already on hand. Many brands, such as Prada and the Kering Group, now pay lip service to “sustainability”; they still produce the majority of their clothes in exploitative and environmentally degrading conditions.

In a review of an early Margiela show, Bill Cunningham refers to Margiela’s work as “deconstructivist” in the literal sense, “where the structure of the design appears under attack, displacing seams, tormenting the surface with incisions.” But Margiela’s designs are also deconstructivist in the theoretical sense: much of his corpus is concerned with setting up oppositions — expensive/cheap, rough/polished — and then overturning those binaries to reveal the way aesthetic judgment is shaped by social convention rather than numinous truths.

It was Margiela’s deep-seated devotion to the technical craft of fashion that led Jean-Louis Dumas, the CEO of Hermès, to select Margiela as the house’s new designer in 1997. Many fashion insiders were appalled at the prospect of the avant-garde Margiela taking over the aristocratic house of Hermès, while others worried Margiela would be too predictable, applying his well-established tropes to the Hermès brand, by, for example, reworking their silk scarves into dresses. Yet Margiela’s approach to the moribund house was neither the shock therapy nor the kitsch many in the fashion industry had expected, but instead a thoughtful refinement, distilling the Hermès style by cutting away the extraneous and emphasizing the beauty of the rich materials.

Saturated in Hermès orange, “Margiela, les années Hermès” makes the convincing argument that Margiela did not do all of his best or most lasting work under his own name. Whereas his designs at Maison Martin Margiela revealed the semiotics and physical construction of garments, Margiela’s work at Hermès hid his tailoring techniques. In the case of one cashmere sweater on display, he developed a knitting process that eliminated seams entirely in order to create as comfortable a garment as possible. He also redesigned the company’s gaudy, gold button logo, replacing it with a six-holed horn button, which, when stitched onto a sleeve, formed the letter H.

Margiela continued to pursue notions of time and timelessness, but for Hermès, he did so through designs that could be repurposed and disassembled, depending on mood, climate, and occasion — an antecedent to what we would now call “slow fashion.” Margiela’s Hermès designs often featured modular components: minimalist trench coats with removable collars and sleeves, a skirt with zippable layers (reminiscent of his 2D collection), a deep V-neck top called the vareuse that could be shrugged off and tied at the waist in a single, casual gesture. The exhibit demonstrates the movement and adaptability of these garments with vertical screens showing lifesize models, many middle-aged or older, slowly fastening, buttoning, and twirling in the clothes.

Margiela’s tenure at Hermès came to an end in 2003, the year after he sold Maison Martin Margiela to Renzo Rosso, president of OTB Group. After the deal, Meirens retired, while Margiela gradually shifted his creative duties to other members of the design team. The collections on display at the Palais Galliera from the Rosso period are noticeably safer than their predecessors and more commercial in their appeal. Basics and replicated items (like the ubiquitous GAT sneakers), which were once a lovingly conceptual nod to fashion history, have come to represent an ever-larger share of the brand’s revenue. Margiela’s creative dive reached its nadir in 2012, when the house collaborated with fast-fashion giant H&M to create a capsule collection on the cheap.

Throughout his career, Margiela designed most of his clothing for artistically inclined women who weren’t trying to look sexy or flashy, but, by the late aughts, a new group of consumers had adopted Margiela as their holy grail: American rappers. Neither exhibit tells the story of how hip-hop came to embrace Margiela, but it is crucial to understanding what Margiela’s brand means today. The keyword “Margiela” appears in the database of rap songs on Genius.com too many times to count, but a few highlights include A$AP Rocky’s line about his gold Margiela sneakers (“My Martin was a maison / Rocked Margielas with no laces”), or the hook from a 2014 track by Future: “1500 on some Maison Margielas.” Yet Margiela is most closely aligned with Kanye West, whose devotion to the house is unrivaled. For his 2012 Yeezus tour, West collaborated with the brand to design a custom wardrobe, including dozens of jewel-encrusted face masks that he wore while rapping his now well-worn line: “What’s that jacket, Margiela?!”

Even as the brand has been embraced by rappers, Margiela’s history has remained under the radar, allowing the designer’s influence to spread obliquely among fashion insiders. A younger crowd is now beginning to discover Margiela thanks in part to his acolytes, such as Demna Gvasalia, Gosha Rubchinskiy, and Virgil Abloh, who have come to dominate the fashion industry. Margiela appropriated and recycled designs in new and interesting ways, but the current crop of Margiela imitators seem to be merely recharting the same territory. Gvasalia, an alum of the house, created an autumn/winter 2018 collection for Vêtements that includes a jacked version of the Tabi boot. In a statement to the press, Gvasalia asserted that Margiela was a “philosophy” rather than an atelier, and therefore the boots were not knockoffs but an homage.

Over the past decade, the Margiela brand itself has shifted toward more accessible and frankly boring designs, while many of his once provocative aesthetic propositions have been absorbed into mainstream fashion vocabulary. With John Galliano now at the helm of the house, the brand has dropped the “Martin” to become “Maison Margiela,” trafficking in the same kooky bird-lady looks Galliano pursued earlier in his career. In this moment of renewed interest, the two Parisian exhibits are a welcome reminder of the full range of Margiela’s groundbreaking oeuvre. Though neither show reveals the man beneath the mask, they do make clear just how radical his vision once was, and still is.