An interview with Marwa Arsanios

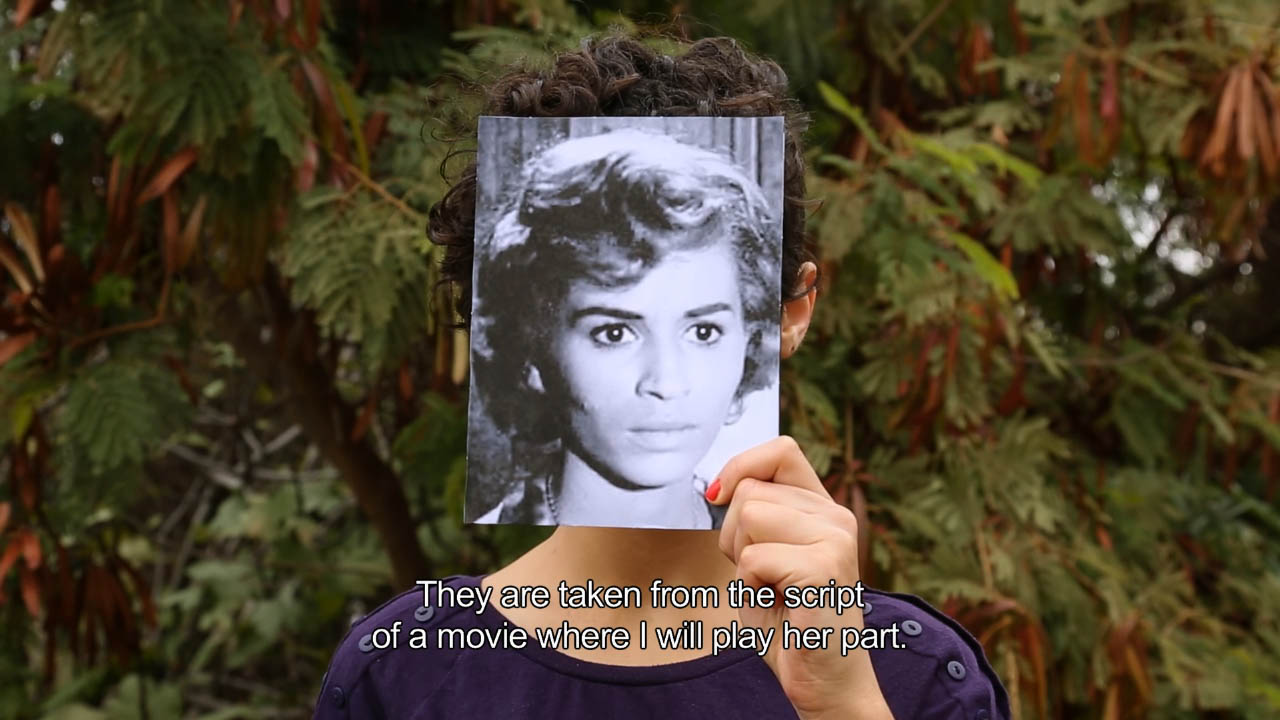

Marwa Arsanios. Have You Ever Killed a Bear? Or Becoming Jamila. 2014. Video, color, sound; 28 min. Courtesy the artist.

History is a nightmare, but it’s the only dream we’ve got. For several years the artist Marwa Arsanios, based in Beirut, has been excavating the lost ideals of midcentury Arab society through an unexpectedly fertile source: back issues of the state-owned Egyptian cultural magazine Al-Hilal. Its depictions of modern women, utopian urbanism, and swift industrialization haunt the artist’s penetrating videos, performances, and research projects — which examine the post-Arab Spring world with historical awareness and sometimes biting irony. Whether looking at Algerian independence heroes or Lebanese architectural schemes, Arsanios’s gaze on the past elucidates the misfortunes and the possibilities of contemporary Beirut, and of the world at large.

Arsanios, born in 1978, has exhibited at the New Museum, the Centre Pompidou, and the Istanbul Biennial, as well as at film festivals such as the Berlinale. She is also the co-founder of 98weeks, a project space in Beirut’s gentrifying Mar Mikhaël neighborhood — which now leads a nomadic existence after losing its lease last year. We meet in downtown New York, where Arsanios had just finished installing her solo exhibition “Notes for a Choreography” at the nonprofit Art in General. × Jason Farago

You began the works that constitute the Al-Hilal project in 2012. Where did you discover the archive?

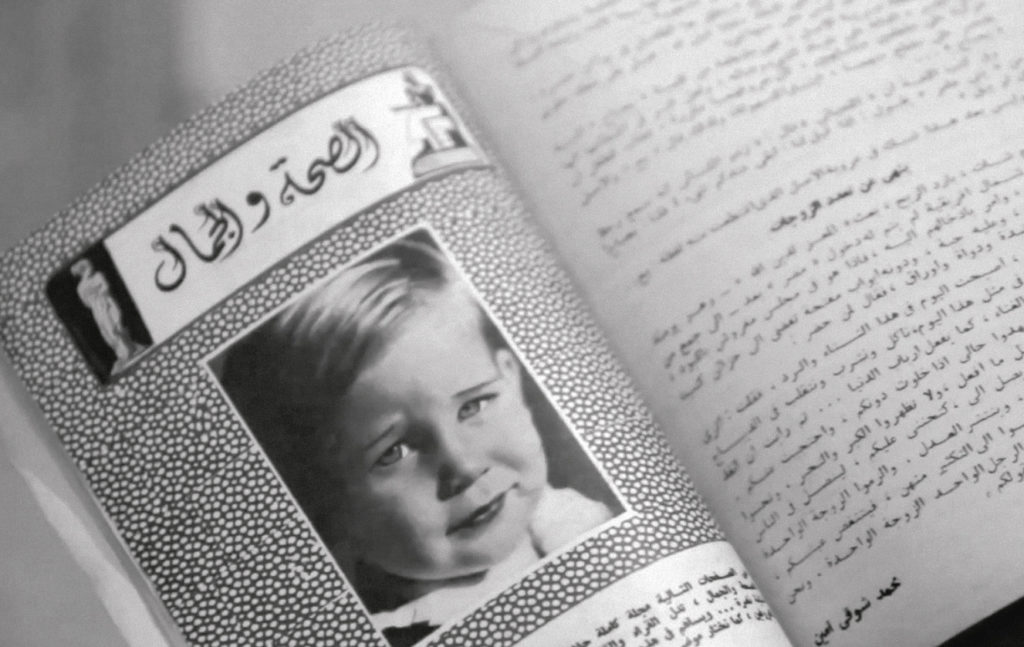

A friend of mine had this collection of old magazines, mostly dating from the 50s and 60s. Al-Hilal was printed in Egypt, but it was a pan-Arab magazine. It was a culture magazine, but it was very politicized. And the magazine was obviously a state project, because all magazines were nationalized during the era of Arab socialism, during Nasser’s regime. This was one of them. Everything that appeared in the magazine is a state project, or a Nasserist project.

Was it a women’s magazine?

It wasn’t particularly a women’s magazine, but part of Nasser’s project was women’s liberation. There was a feminist project, although a quite conservative one. Al-Hilal advocated a kind of secularism that was trying to incorporate Islam. It wasn’t Islamist as such, but it tried to understand and incorporate Muslim society. So, there were a lot of socialist ideals, socialist ambitions, like industrialization and social housing — urban issues appeared frequently. Articles looked at the category of the woman, the peasant, and the worker, and they were talked about in the magazine in quite distinct ways.

And these were presented as kinds of citizens who would participate in the building of a new nation. A new political subject.

Exactly: new political subjectivities, and a new political collective. There were very much these ambitions back then. Also, in a weird way, although Al-Hilal was writing about the working class, they were really trying to think about what a middle-class Egyptian or Arab person would be like. What would a middle-class Egyptian or Arab read? How should a middle-class Egyptian or Arab woman behave? So it was trying to form these new middle-class subjectivities and subjects as well.

How many years did you look at?

Two whole decades. The magazine changed a lot over the 50s and 60s. You can map how all of the different political events are affecting the editorial, especially after 1967: the Six-Day War, and Nasser’s last years. All of these moments affect the writing, the editorial, the discourse.

So the history of the postwar Arab world was already mediated from the time you started the project. It wasn’t as if you started with history, and then looked at how it was represented through images. The images and the articles come first

And that’s an interesting way of looking at history, through magazines, through ephemera. History as it’s being written, by writers who wanted to craft it. Al-Hilal was a magazine for a mass readership, and it used a popular register to address these issues. Also, a magazine forces you to offer an instant perspective on things. It’s another pace of writing.

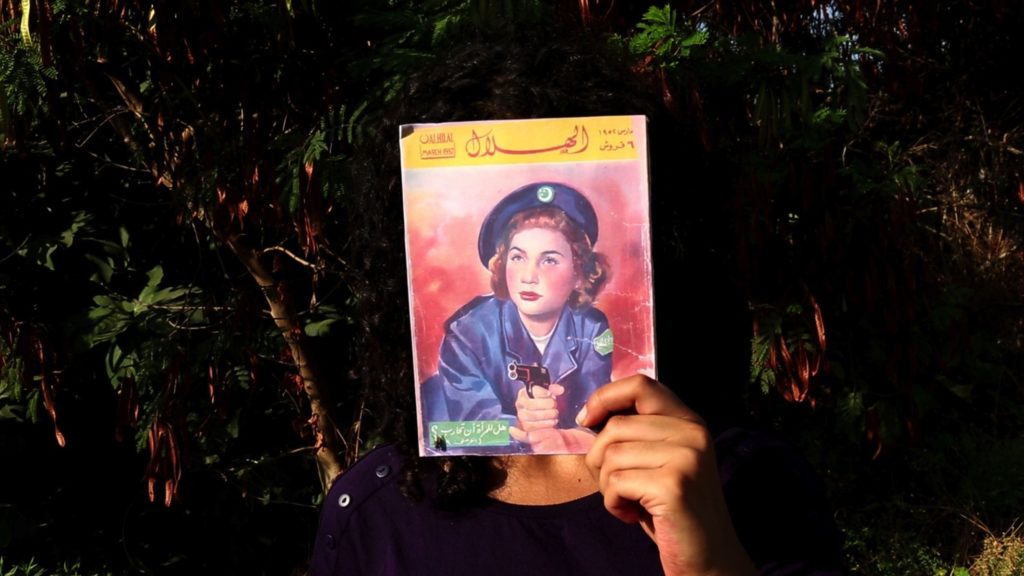

As for the images, a lot of the covers that I use in Becoming Jamila were commissioned by famous illustrators, painters and artists. They were artworks. Photography didn’t appear in the magazine until 1962, and I like that earlier period, which expresses a utopian image of the nation. I’m fascinated by how grand national projects were represented before photography, how painting and illustration could serve as a space to imagine another world, although in a very naïve way.

After 1962 photography came in, and with photography came another kind of imagery, especially of women’s bodies. Actually, many of the images that were used inside the magazine were appropriated from other magazines, often western magazines like Reader’s Digest. They just cut and pasted them. The whole construction of Al-Hilal was quite precarious.

We forget too often that from the 1950s until the oil crisis, the Middle East was a place where governments’ modernization and urbanization efforts could extend to utopian heights. A few years ago I saw a show at the Center for Architecture that looked at modern architecture in Baghdad before Saddam Hussein. Frank Lloyd Wright wanted to turn Baghdad into this fantasia with floating islands; he even proposed a Garden of Eden.

That beginning of the oil boom, before the crisis…. When you look at it now, in a very anachronistic way, you can see it’s a very naïve manner of looking at the world. Maybe it was good for me to look at that period, and its ideals, during the so-called Arab Spring. I was living in Beirut at the time, and I think it was interesting to look at these magazines with the backdrop of what was happening. Something important happened in 2011, though looking at what’s happened since then, I don’t think that the Arab Spring could have led to anything else. Looking at the 50s and 60s, I realized just how fucked up these societies were, how brutal and how violent. These regimes, and what came out of these regimes, are the reason the Arab Spring turned out like this.

What came out of anticolonial liberation movements were horrible dictatorships, and these horrible nation states were a model that couldn’t work. And I think 2011 was really questioning the very model of nation states. Maybe this is what is still going on. Everything is collapsing. Let’s face it, the model of liberal democracy in not working very well in America either.

That’s why I’m so interested in your project: it looks back at this last moment when it could have worked, and it did not. There’s a funny kind of promise in a lot of your art. You watch the videos with a tragic knowledge in the back of your head that nothing will pan out the way they think it will. And yet there’s a melancholy beauty to the dream of a new nation, a new woman, a new body. A new architecture, too — you frequently turned to modernist buildings in your early work.

One of my earliest videos [I’ve Heard Stories 1 (2008)] is about a murder that took place at the Carlton Hotel, which was one of the best hotels in Beirut before the civil war. That came from a similar interest in utopian infrastructures: how modernism could function as a universal unit, something that could be sent out into the world, exported, implanted. It’s another form of western culture that is struggling to live, struggling to continue.

Is the Carlton still standing?

The Carlton has been destroyed. Whereas the building on Acapulco Beach that appears in my other animation [I’ve Heard 3 Stories (2009)] is still there, but it’s totally transformed. How these places have taken on new, private functions is also important. The utopian moment was also such a repressive moment. It’s very similar to the idea of the American dream, in a funny way. You can improve; you can go further; you can climb up the social ladder if you want to. It’s your will as an individual, rather than the fucked-up system that you’re in, that supposedly determines your progress. That, I think, is what ultimately made these utopian projects so self-destructive.

It also explains why artists like you, who didn’t live through that period, would find it so interesting. For people our age, who, to be blunt, have always had a little less hope than our parents’ generation, looking at those dreams and their malfunction — looking in a forensic way, as a sort of post-mortem — can be helpful to explain why we don’t have our own language for grand projects.

We realize also that what they have created, what they have been part of, actually forms the crisis we are facing down now. The inheritance is a monster.

You mean Lebanon?

Not only that. Also the whole global economic system. It goes beyond places. My work is very related to where I am, embedded in the context where I live. But because I function more and more in a global art economy, flying around the world, the issues in my work are also becoming more global.

In Becoming Jamila, the other major component besides Al-Hilal is Gillo Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers (1966). The actress is your video is preparing to star in a new film about Jamila Bouhired, one of the leaders of the Algerian anticolonial struggle, who’s of course one of the supporting characters in The Battle of Algiers. You even remake one of Pontecorvo’s most famous scenes, in which Jamila plants a bomb in a café. Maybe you can tell me about cinema, and how that fed into the project as well.

It came from the magazine first. I kept reading about Jamila, and I couldn’t figure out who Jamila was. Of course, I knew the film, but I hadn’t connected it directly to her. I started going into the different representations of Jamila, and how she was represented in cinema, because there were many other films made about her. Also how she was represented in Al-Hilal — Nasser really used her as part of his propaganda project. She appeared on the cover several times, holding a gun, representing the courage of Algerian women. I thought that the idea of acting and of political representation were intimately related. What does it mean for one woman to represent a nation’s women? There’s a metaphor there of acting, of playing a role. That’s where cinema came in.

So I was trying to look at the relationship between this woman and her heroic image. Jamila is still alive, but she’s no longer a public figure. She didn’t go into politics, whereas all her ex-comrades in the FLN, men and also women, all went into governmental positions in Algeria.

Your film isn’t a remake of The Battle of Algiers, though. It’s a story about a fictional actress who is planning to star in a new film. Yet The Battle of Algiers was a contemporary film; Algeria had only just won its independence. The film in Becoming Jamila, if it were ever made, would be a film about events half a century old.

But this is why I didn’t make a film about Jamila; I made a film about a film about Jamila. The Battle of Algiers was a contemporary film, whereas if I were going to really make the film now, it would be a film d’époque, a period piece. That is not the place I want to go. I want to rethink the politics of the 50s and 60s in a very contemporary way. I could have made a film about Kurdish rebels, the women in Kobane, let’s say. I could directly tackle these issues. But I think that in talking about Jamila, I’m also talking about them. And yet at the same time, by reusing and re-abusing Jamila’s image, I’m also possibly reproducing the image of the heroic fighter. Or I’m totally seduced by her, so I’m not actually producing a new politics. I’m always failing to find this new politics, but I still have to try.

The newest component of the Al-Hilal project, the film Olga’s Notes: All Those Restless Bodies (2014), is much more melancholy, I find. You depict half a dozen dancers, and show how their bodies have been implicated, even distorted, by not just artistic but political forces.

It started with this article that I found in Al-Hilal about this dance school in Cairo that Nasser set up. It said that the dance school is producing the “new body” — the dance school producing the “modern body.” Literally, it was saying that. It started there, and I wanted to figure out the dance process, and how the production of the body in dance takes place. One dancer comes from a school in Brussels, and she performs Yvonne Rainer. Another performs a ballet that actually premiered in Cairo. Natacha, the oldest dancer in the film, was in the national dance school in Beirut, approximately twenty years ago. I asked her to re-present a dance that made her famous, but she can’t remember it. The choreographer she was working with at the time was supported by many Arab governments, creating a weird fusion of modern and Oriental ballet, and she was a star dancer. There’s also a pole dancer — there are a lot of pole dancing clubs in Beirut.

The way that these bodies move through space, and move in the frame of the camera, can be very powerful but also upsetting. You see how their bodies have broken down as they’ve got older. There’s also the political resonance. I’m interested in how all of that starts to overlap, especially when you are watching Natacha. It’s a more pessimistic work, certainly.

In 2011, I was so optimistic. Now there’s much more pessimism, which I don’t like. After everything that’s happened in Syria since 2011, I feel what we are living through is beyond, really beyond, the amount of violence any human brain is capable of understanding. And I feel this has affected me in weird ways. You become haunted by it. I have a lot of Syrian friends who are living now in Beirut, who came there from Damascus. And you can’t really keep a distance, it’s impossible. Things are happening so close.

I’ve stopped now, but I used to watch a lot of YouTube things. All the torture. You see the fragility and the vulnerability of the body, and you start thinking about how important what you’re doing is. You’re always questioning it, of course, but it grows exhausting. Is it really important, what I’m doing? I’m so into politics, but maybe I don’t believe in political art in the same way. Of course the work is political in a different way, talking about the body. But if I want to compare it to the previous work, like Becoming Jamila, it’s a different kind of politics. Maybe I’m trying to think of a different kind of politics, but through another means, or another language.

So much of your experience of Beirut has orbited around 98weeks, the project space you opened in 2009.

We had a space, but we lost it. Gentrification. My cousin Mirene and I started 98weeks in 2007 as a research project. We had both just finished our studies in London, and going back to Beirut, we wanted to maintain an extension of that academic environment, but also take it outside of academia. So at first it was just the two of us, and our initial research interests were about spaces in the city: about Beirut itself.

Then, in 2009, we got the space. Five years later, the neighborhood is totally gentrified. And we were part of the gentrification process. We haven’t yet reopened, and we are doubtful of going somewhere else, because what’s going to happen in the next neighborhood?

We talk about this in New York all the time. The artists come and establish a neighborhood and then get pushed out. And it’s true of Beirut as well.

You go to a neighborhood as an artist, and then you make it cool, and then prices go up, and everyone has to leave, including you, but also the people that are living there. It’s a quite perverse process. Now we’re doing our events at different spaces in the city, so we’re back where we started.

What is the independent scene in Beirut like? Are there a lot of spaces like yours?

There are a couple, like Mansion and Marra.tein. We might move in with them, actually. Then you have not-for-profit institutions like Beirut Art Center and Ashkal Alwan, and you have the commercial sector. But Beirut is at a strange junction right now. In the 90s, the arts were living on an international aid economy, with funds from the Ford Foundation, or the European Union. Some interesting grassroots projects started, like Ashkal Alwan. After 1990, after the war ended, the city was a bit like Berlin. After 2004 or 2005, something shifted on the scene. I guess the international funds don’t want to pay anymore, and the war in 2006 didn’t help either. There are still grassroots projects, but now there are at least five different private foundations that are opening. One contemporary art museum that is being built from scratch. Another museum that has been renovated.

But all of this… . The private foundations are fine. It’s the same everywhere. But the other things, they’re costing millions. And you have so many interesting not-for-profits in Beirut, places like Ashkal Alwan, that made Beirut’s art scene and established its intellectual foundations. The art scene in Beirut has never been slick and money-soaked, compared to what has happened in the Gulf. But it’s going toward that, and it’s happening so fast. Beirut is a really small city, and I don’t know how many museums and foundations you need, yet now you suddenly have so many people interested in the arts. I’m suspicious — why? It’s about money. This is scary.

I really wonder what’s going to happen to all of these museums opening in the Gulf in the next ten to fifteen years. If Americans and Europeans don’t want to take those jobs any longer, or if there’s a real disaster with the World Cup in Qatar, which could happen in 2022 — although the humanitarian disaster has already happened, is happening every day.

Me too, I wonder. I really am very suspicious. I’ve been only to Abu Dhabi, not Doha. But now it’s coming home, all these bling-bling things. I’m really suspicious about it. People in Beirut are already discussing this, and they are not happy.

It goes back to the pessimism you were speaking about earlier. It’s not just about the civil war in Syria. It’s about a more global and inevitable economic situation and about the role of the artist in that economy.

You’re a bit stuck, actually. What can you do? How much can you do? You have to find some tools, not stay pessimistic and do nothing. Boycotting, for example, can work, but you have to be powerful enough, or numerous enough. That’s happening with the Gulf Labor Coalition, who are protesting the museums in Abu Dhabi. That’s what happened at the São Paulo Biennial last year.

I didn’t go to São Paulo last year, but I went to Sydney — and it worked there too. The threat of a boycott by artists was enough to get the biennial to break its ties with a company that was linked to immigrant detention camps. When I got to Sydney, though, I was shocked by the anger that government officials or newspapers columnists unleashed on the artists. The message was: we love art, but who do you think you are? Your job is to shut up and make beautiful objects — you’re naïve.

“You’re naïve.” I hear this a lot. Which is the most patronizing, horrible thing you can hear. And there is a new kind of artist that is coming up now that’s comfortable with that, a super-professional artist who doesn’t really care.

You keep on trying. You know that most probably you’re going nowhere. But you keep on trying. This is a strategy — this is being an artist, actually. Trying, trying forever. It’s the opposite of a utopian model. Making a space to think, to take time, to do research, to just talk, sit and talk for hours, over a drink, slowing down everything. This is a way of trying: slowing down every possibility of production. Thinking about the process, thinking about the research. When everyone wants you to just make stuff, thinking is also an artistic act.