Mountains Between Us

by Erica X Eisen

In recent years, modern conservation practice has coalesced around two simple mantras: “minimum intervention” and “reversibility.” The Burra Charter, a set of international standards for cultural heritage management adopted in 2013, defines “minimum intervention” as doing “as much as necessary but as little as possible.” This is often understood in opposition to restoration, which goes beyond preserving what remains and attempts to return a work of art to its assumed original state. “Reversibility” is the idea that any treatment should be able to be undone if necessary, recognizing that future conservators may have a better understanding of the object in question or more advanced technologies at their disposal. To study conservation today is to understand that your well-meaning intervention might nevertheless be the worst thing ever to happen to a work of art. It means going about your work trailing a broom behind you, lest you need to erase your own footprints.

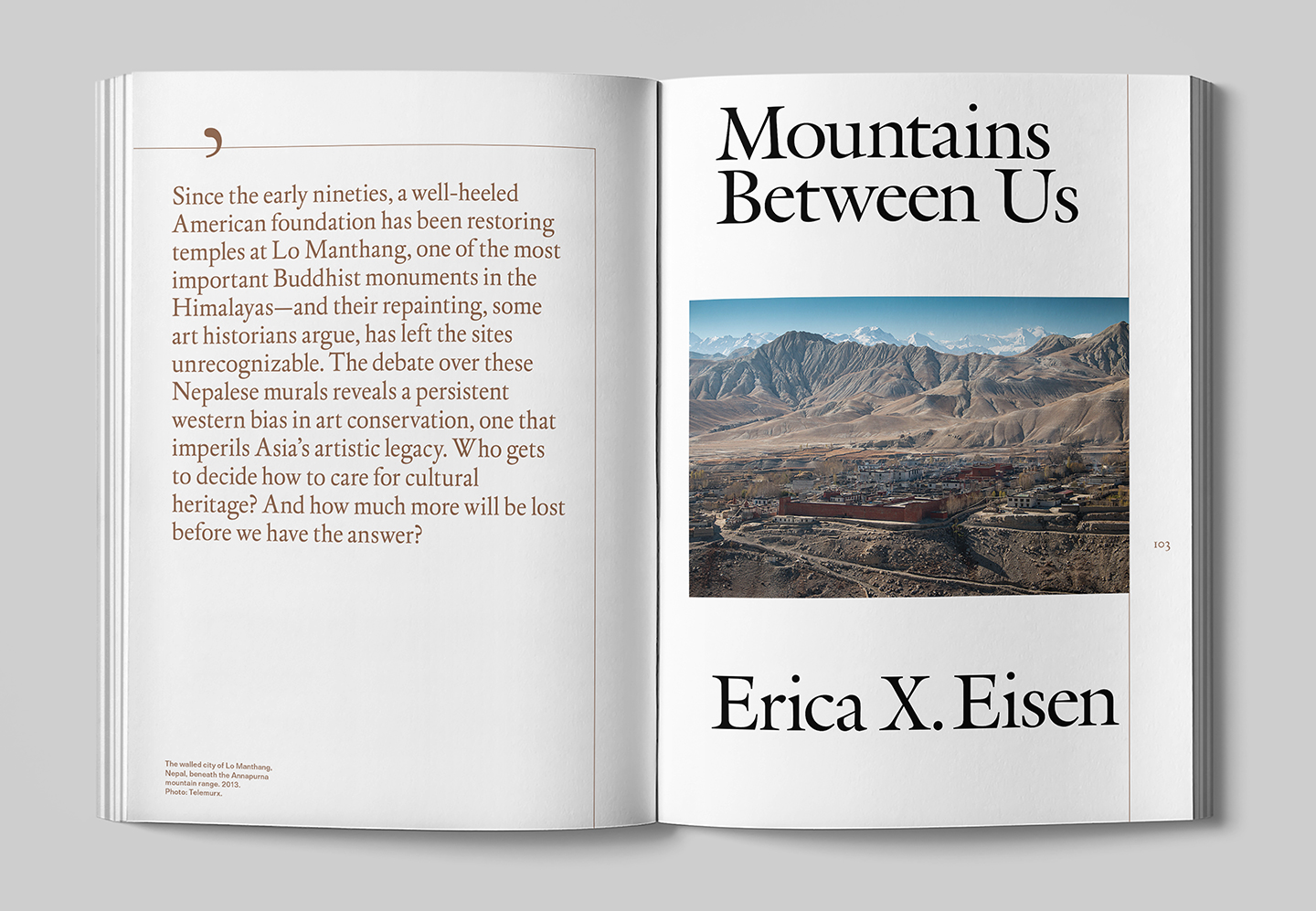

That, at least, is the ideal. But the reality, as Luczanits observed at Lo Manthang, can deviate dramatically from professional standards. And Asian art is particularly vulnerable to poor conservation treatments, in part due to a persistent bias in the field toward western artworks, research, and training. Several of Buddhism’s most important monuments already face threats from climate change, economic development projects, burgeoning tourism, and even religious extremism. Aggressive restoration work may be a milder kind of debasement, but it is doing damage all the same....