Natural Causes

by Annie Godfrey Larmon

The Lightning Field, Spiral Jetty, Double Negative: climate change is already transforming America’s masterpieces of land art. It will, and must, transform our judgment of them too

The final stretch of road to Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, in Rozel Point, Utah. 2009.

I.

On Friday, May 29, 2015, at the end of the half-hour car ride from the Dia Art Foundation headquarters in Quemado, New Mexico, to Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field, my sister, an archaeologist, asks our driver about the Pueblo sites in the area. She winces as he shows us black and white ceramic sherds he has plucked from the high desert landscape, with little regard for the niceties of excavation. It seems apt to be discussing the ethics of displacement and conservation as we pull up, at around three in the afternoon, to the small cabin at the edge of De Maria’s earthwork of 1977 — a piece that must be experienced in geographical isolation for an extended duration.

Fashioned out of materials salvaged from homesteading huts, the cabin is empty, save for some Shaker-style furniture and a woodstove. The intention is to push us outside, where feral rabbits tremble in the dusty, sun-bleached scrub, and where 400 polished, stainless steel poles stretch in a grid measuring one mile by one kilometer. The poles rise, on average, to a height of just over 20 feet — taller or shorter depending on the terrain. De Maria designed them so that a pane of glass could rest evenly on their sharpened tips. When I first see the poles, I imagine this projected ceiling, a fragile assertion of modernism’s order and transparency in the landscape’s windy distortions.

The light of the mid-afternoon bears down such that the poles are still more astounding in their concept than in appearance. Aside from the slight threat it carries as potential weather attracter, De Maria’s atheist geometry feels sort of banal. There is a no-photo policy, and my sister and I piously stow our phones. De Maria, who died in 2013 had often been criticized for exerting tight control over the site, in ways unlike other classics of American land art — quite the opposite of his colleague Robert Smithson’s decision to embrace entropy in such earthworks as Spiral Jetty (1970), another Dia holding. But entropy does its work nevertheless: I can’t help but notice that the verdant scrub of John Cliett’s iconic 1979 photos of the site is now balding, scorched.

A few years before Smithson traveled to the Great Salt Lake, where he would create Spiral Jetty, he took a series of photographs of savorless sites in his hometown of Passaic, New Jersey — bridges, water pipes, sandboxes — sites that were simulacral in their ubiquity and homogeneity. He designated these prosaic spots in the suburban landscape as “monuments.” “Instead of causing us to remember the past like the old monuments,” he wrote later, “the new monuments seem to cause us to forget the future.” Today’s monuments, fifty years later, bring us the future as they compromise it. That is, 2018’s monuments are the fiber optic cables that conduct financial flows and the impenetrable Google data centers tucked into the same nondescript suburbs — the obdurate stuff that allows us to uphold narratives of immateriality and clouds and real-time.

Our monuments, like Smithson’s, are functionally invisible; but ours aid in abstracting the blunt realities of poverty, labor, and ecological ruin. My sister and I have turned to the gestures of earthworks in order to localize such abstractions, to seek some kind of antidote to our monuments’ environmental obfuscations. Of course, the implications of The Lightning Field — like any such phenomenologically oriented artwork — have shifted over time. De Maria could not have anticipated the ways in which technology would shape perception and duration itself. So here we are, technology-less, obligated to confront what Smithson would call our entropic “physical dissolution” for De Maria’s prescribed 24 hours.

And because of this unmediated reckoning, we notice things. We pocket beers and head into the crusted, hollow vegetation, its structural integrity compromised by some burrowing creatures’ infrastructure underfoot. The sky is girded only by far-away mesas, and the heat feels like a compress. “A simple walk around the perimeter of the poles takes approximately two hours,” De Maria instructs in a text from 1980, but “the primary experience takes place within The Lightning Field.” Our impulse is to find some logic for navigating the poles, as though they are a score. It seems at first that we shouldn’t speak, shouldn’t disrupt whatever transcendent perceptual mode we might arrive at, but we do. The poles are like rosaries; their repetition coaxes confessions. We allow ourselves to be distracted, to let the poles structure a social space.

As the light begins to wane, the festering, lambent colors of sunset strike the polished steel at an angle that seems to separate the architecture from the ground. The poles no longer disappear into the blue of the distance, but become explicit; their shadows grow and their tips send sparks of light. But just as soon as the sunset gives us this vision, it takes it away.

The desert is different at night. I’ve lived mostly in the mountains of New Hampshire and the spectral architecture of New York City — topologies that enwrap you, that encourage interiority. The infinitude of the flatland seems to do the opposite in the dark, as though structure itself were peeling away from us like dead skin. We return to the cabin, the only significant structure for some 9,000 acres, which Dia purchased in 2008–09 to protect The Lightning Field’s view shed. Outside, the wind pushes against the salvaged walls with what seems like enough force to flatten them.

There is no lightning.

We sleep for three hours before rushing into the cold for the sunrise. The cresting sun saturates the colors of the ground cover; the posts radiate like sentries from another planet, their surfaces move with the changing sky. I want to be inside the grid and outside it at once, to harness something of the energy gathered there, to observe the system materialize and dematerialize, cohere and disassemble from an object to a series of objects. Of course, The Lightning Field is not about lightning, or about anticipating a Prospero-worthy performance of the sky. It is about heightening one’s receptiveness to time and space. It is about making the environment ineluctable. And yet in the decades since De Maria’s poles were first erected, the environment — and its fever-induced tantrums — have become increasingly difficult to ignore.

In 1980, De Maria wrote in Artforum: “Engineering studies indicated that these foundations will hold poles to a vertical position in winds of up to 110 miles per hour.” But what if the winds exceed that? By 2080, according to a recent NASA study, the droughts in the American southwest will be worse than any in a thousand years, including those that “dried up all the rivers east of the Sierra Nevada mountains” and may have eradicated the ancient Anaszai civilization. Last July, David Wallace-Wells cited this projection in his instantly viral New York magazine article, in which he issued a litany of facts about global warming as a clarion call: The Arctic permafrost is rapidly melting, and could release unprecedented amounts of carbon into the atmosphere; Miami and Bangladesh may be underwater by the end of the century, even if we stop burning fossil fuel in the next decade; and what’s more, “the five warmest summers in Europe since 1500 have all occurred since 2002.” Indeed, in February of this year, the Washington Post reported on a historic thaw at the North Pole, with several independent analyses corroborating that “the temperature averaged for the entire region north of 80 degrees latitude spiked to its highest level ever recorded in February. The average temperature was more than 36 degrees (20 degrees Celsius) above normal.” Meanwhile, a recently leaked draft report (the final account will be published in September) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicates that keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, the more ambitious target of the Paris climate accord, is “extremely unlikely.”

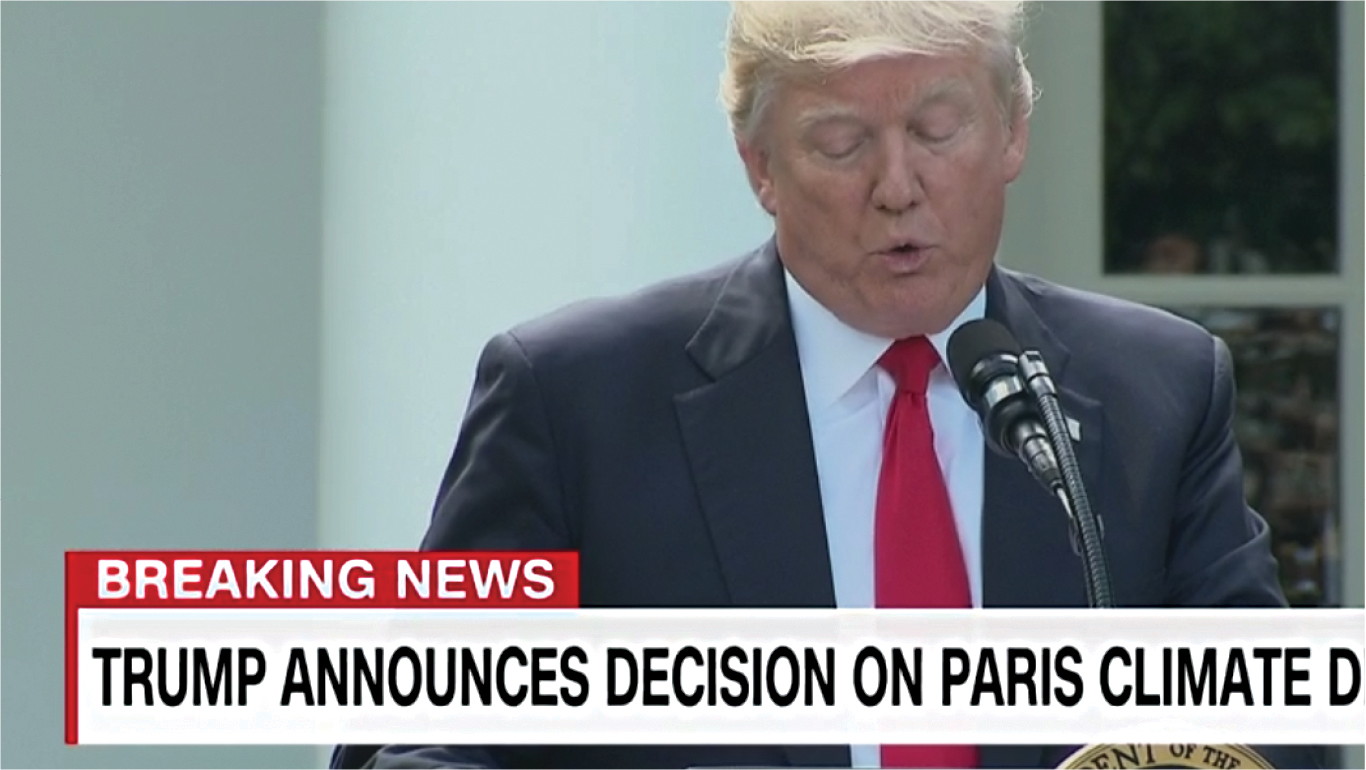

The IPCC report puts the onus on such countries as the United States to make, in a matter of decades, radical changes that include “rapid and deep” emissions cuts and “sucking already-present carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.” Of course, in the face of this exigency, the Trump administration has rolled back environmental protections, advocated for dubious “clean” coal, and announced the US will withdraw from the Paris Agreement in 2020. What’s more, according to the International Energy Agency, the US is poised to become the world’s largest oil producer, exceeding 10 million barrels a day this year. The justification for such regressive policies, we are told, is not corporate profit but “job creation,” to which the scandal-trailed Scott Pruitt has completely reoriented the Environmental Protection Agency.

Under the fraudulent pretext of saving “the American people” more than $300 million in regulatory costs, Pruitt’s EPA this year began efforts to roll back the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, which the agency admitted would have saved the lives of up to 4,500 Americans each year by 2030. Pruitt has suspended the Waters of the United States rule, which kept carcinogens and pollutants out of American rivers and streams. (Even looking through the egregiously myopic lens of cost burdens, these acts of ecological vandalism are regressive. The EPA, in 1997, released a cost-benefit analysis of the Clean Air Act and estimated its total monetized health benefits from 1970 to 1990 at $22.2 trillion.)

Pruitt has not conceded the reality of climate change, even asking once whether global warming “necessarily is a bad thing.” Yet even we who acknowledge the realities of the crisis aren’t exempt from holding climate change data at arm’s length. Our own cost-benefit analyses can’t always register the ramifications of our quotidian decisions, and the magnitude of the issue makes it abstract. More cynically, our resistance to the bigger picture might boil down to the Stanford marshmallow experiment, and our aptitude for delayed gratification — and separately, worse, our biological drive to protect our young — is just shoddy. It’s a problem of scale, and of narrative: we can’t see the world in a grain of sand, and vice versa.

In what ways, given this context, must we reframe our understanding of earthworks — propositions that hinge on our relationship to the environment, to institutions, and to ourselves? The most famous earthworks — The Lightning Field, Spiral Jetty, Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973–76), and Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969–70) — were produced in the early days of the environmentalist movement. Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962, which inspired the passage of the Clean Air Act (1963), the Wilderness Act (1964), the National Environmental Policy Act (1969), and, in 1970, the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency. When these earthworks were conceived, federal policy was only beginning to grapple with the effects of human industry on ecology. In the five decades since, the world population has more than doubled and the optimism that accompanied the formation of the EPA (by a Republican administration!) has been corrupted by private interest. Climate change is transforming land art; that much is already clear. But climate change also necessitates another, critical transformation: one that accounts for increasingly destructive temperament of our government, assesses land art’s own colonization of space, and indeed, factors in the carbon each work requires to be seen.

II.

To get to Michael Heizer’s City from almost anywhere, you need to fly into Las Vegas. Just off the Strip, is one of the city’s tackiest eyesores: a 64-story, gold-plated hotel advertised as “undeniably Trump.” The US president’s namesake hotel also boasts an 11,000-square-foot spa and outdoor roof deck pools with private air conditioned cabanas. Given such tone-deaf-to-the-desert excesses, it is hardly surprising that one of Trump’s early acts as president was to order Ryan Zinke, the interior secretary, to review the size of 27 national monuments, with an eye toward opening protected land up to development and drilling. Among them is Basin and Range, a 704,000-acre area two hours north of Las Vegas, which the Nevada senator Harry Reid encouraged Barack Obama to landmark in 2015. So far Zinke has not reclassified Basin and Range, but any change in the land’s status may reinvigorate a botched government plan to build a railroad that would carry nuclear waste to a proposed repository within Yucca Mountain, near the border with California. The track would run through several Native American rock art sites and plow directly through the land surrounding Michael Heizer’s opus City — a project he started in 1972 and won’t complete until May 2020.

Heizer’s mile and a half-long installation in the rural desert of Lincoln County, Nevada, comprises five complexes inspired by Native American mound-building and pre-Columbian ritual cities like Teotihuacan. Like much of Heizer’s work, City is an exercise in displacement — a mining project, wherein native sediment is mixed with cement to form positive volumes from the negative ones the artist excavated. Michael Govan, the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, raved to the New Yorker about Heizer’s work: “Mike started the idea that you can go out in this landscape and make work that is sublime. There is nothing more powerful, romantic, and American than these gestures that in Mike’s case have taken his whole life.”

Sublime and romantic it may be — we wouldn’t know. We try to visit City, my sister and I, but it won’t be open to the public until it’s finished. Needless to say it has generated a cultish status because of its inaccessibility. But I wonder, especially in light of this work’s entanglement with climate change denying policies, what good do such sublime, romantic works do in this moment of ecological precarity? On the one hand, its existence led to the preservation of the surrounding land. Harry Reid was captivated by the work and inspired to save it. “It’ll be there for a long time,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s going to be there forever.” It’s a best case scenario: work that engages the environment inspires real environmental action. On the other hand, denizens of the art world will now fly to Vegas, perhaps stay overnight in Trump’s hotel, rent cars to brave the indifferent desert, and expand their appreciation for the environment along with their carbon footprint. Govan is therefore correct to call Heizer’s project an American gesture: at its core, it is a project of expansion. Manifest destiny.

Photo: Tom Vinetz. © The Triple Aught Foundation.

It is unfair to blame this problem on earthworks alone. After all, plenty of people fly to Mexico City in order to trek to Teotihuacan. But Teotihuacan was an actual city. City, ultimately, is a carbon-guzzling spectacle that reminds us not to guzzle carbon. Heizer often talks about John Muir, the 19th-century environmentalist and Sierra Club founder, who once camped at the site of City. Muir dedicated his life to protecting the American landscape from industry and agriculture and what he called the “hooved locusts” of livestock. If Heizer truly shared his ethos, he would, after securing the easement, shutter City to the public, safeguarding the surrounding land from jet-setting locusts. But Heizer’s project shouldn’t be confused with environmental activism. His aim is to inspire awe, to enter mythical ranks, to dedicate his physical being to a monument that might contain him, outlast him, preserve him.

Heizer is constructing City from worthless materials — rocks, sand, and concrete — sourced on site as a bulwark against future social instability. More precious materials, Heizer points out, are often reused in a time of need. “Incas, Olmecs, Aztecs,” he told the New Yorker, “their finest works of art were all pillaged, razed, broken apart, and their gold was melted down.” Heizer’s goal is to produce a monument that, in material terms, won’t be worth the effort to destroy. In the end, the work’s pretensions to eternity are more than simply anti-social; they undermine the artist’s stated ecological persuasions.

City finds itself in a tough spot, conceived in the high noon of land art and arriving under the moon of fake news. But the more I think about it — and despite my own desire for such sublime experiences, despite my admiration for Heizer’s cool, monolithic geometries — the more tempted I am to compare his project to Trump’s air conditioned, mountain-view cabanas. Each is a luxury seat from which to ignore the earth’s imminent shortage of H2(EAU), which happens to be the name of Trump’s poolside restaurant in the desert.

III.

My sister and I fly in late to Las Vegas, and we can only find a room at a smoky circus of a hotel, flanked by rooms of raucous frat boys. In the morning, we rent a Prius and start the hour-and-a-half drive to Double Negative, the void Heizer excised from a remote mesa in 1969. We make a detour to pass through the Valley of Fire State Park in the Mojave Desert, its red Aztec sandstone interleaved with gray and tan limestone. We pull over and climb on the undulating, lava-like formations from the Mesozoic era; we see petrified trees and Anasazi petroglyphs. As we leave the desert, our cell reception becomes blinkered, and Google Maps begins to function as though we were trying to navigate a single pixel.

We find what we think is the unnamed road we are supposed to turn onto and cruise up the Mormon mesa where the road degenerates into kindling-dry terrain. The low undercarriage of our Prius is suddenly a problem — the wiry sage brush covering the ground is known for erupting in flames when cars drive over it. I get out of the car and help my sister inch through the brush to a narrow, navigable path that hugs a scalloped cliff overlooking the muddy Virgin River; we spot a car that has careened over the edge and speculate about the circumstances of the accident. Unsure of our coordinates, marginally terrified, we approach a man sitting in a lawn chair not far from the ledge. He could be a Duane Hanson sculpture. He has enclosed himself within a border of small rocks and has a sign that reads “Welcome Polish Negative.” Relieved to know we are close, we stop, curious. Our guy had recently purchased the land he was occupying and had dedicated himself to this absurdist gambit; he recalled when Heizer came out to the desert with dynamite and tractors and decided he would make a comparable gesture, sans sweat. He is clearly ready to take the piss out of us, traveling so far to see, by his estimation, literally nothing. He never reveals whether he is Polish or not, but he is still there, alone, when we leave.

I won’t say that Double Negative isn’t nothing. When we find it, we spend an hour in the dusty heat, walking throat-dry through the two box-like troughs, each 50 feet deep and 30 feet wide, that Heizer carved to intersect a chasm. They face each other, so that the interior spaces are aligned along a single axis that extends 1,500 feet. I appreciate the semantic game of the work — negative space becomes doubled where the gestalt of the excised shape overlaps the naturally occurring cleft of the mesa — and I think about the Sisyphean task of its facture: Heizer describes the work as a 240,000-ton displacement. I understand that it is best viewed from the air. While Double Negative’s geometric cuts were originally clean, the shape has eroded in the decades since it was created. Already in 1976, critic and curator Lawrence Alloway wrote that “the sides are taking on the rounded edge and the natural collapse-curves of the sides of the mesa. In fact there has been a rockfall in one of the cuts recently.” This trend has only accelerated. We are hesitant to enter the trenches for fear of disturbing them. At first, Heizer toed the entropy party line; he intended the piece to submit to time and erosion. “Say the work lasts for ten minutes,” he said in 1969, “or even six months, which isn’t really that long, it still satisfies the basic requirements of fact.” But he has since reversed course, hoping to find money to maintain it in perpetuity, even as the climate shifts.

Six months is a flash in the pan compared to the 48 years the work has persisted, but forever? I can’t understand perpetually maintaining a work that is formed from an environment we now understand to be historical, not eternal. If Heizer already knew in the 1970s that six months isn’t really so long, he should likewise understand that nature inhabits timescales we can’t fully fathom. The idea of Double Negative was that it would challenge the temporality of artworks, that it would cause the manmade to intersect with the natural, that it would go the way of its surroundings. Left untouched, the work would erode, its hard-edge cuts would buckle and eventually fold, leaving sloping indentations in the mesa that will eventually flatten or crumble into the valley. Double Negative will be a positive, or a single negative, or it will be fluid — dust turned to mud in the Virgin River. To maintain the cut now would be to aestheticize a radical gesture, to render it moot. It would take something away from this unpredictable study of mass, volume, density, and space. When does Double Negative cease to be — when its physical reality contradicts the terms of its title, or when a maintenance crew restores the work even as the Mormon mesa shifts and recedes around it? I’d wager the first option is the better one. In fact, to trace the work’s changing form over time is to give shape to the accelerations of climate change: a decade of erosion in the 1970s likely looked very different from a decade of erosion today.

Of all of the land artists, Smithson seems to have been the most aware of the movement’s indulgences, hip to the false perception that these works about the environment were also about environmentalism. He had a Gay Science nihilism regarding the energy crisis of the 1970s. In 1973, just two months before he died, at 35, in an airplane crash while photographing his unfinished work Amarillo Ramp, Smithson proposed that “waste and enjoyment are in a sense coupled.... There’s a certain kind of pleasure principle that comes out of preoccupation with waste.”

I’ve never been to Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, I’ve only seen it in pictures. The 15-foot-wide mass of basalt rock and earth, winding two-and-a-half turns, extends 1,500 feet into the the Great Salt Lake in Utah. It isn’t spectacular — Geoff Dyer described the lake as “congealed, like a dead ocean on a used-up planet.” Smithson selected the site for its prehistoric qualities — microbes give the lake a reddish coloration — but also for its imbrication in a visibly manmade landscape. “A series of seeps of heavy black oil more like asphalt occur just south of Rozel Point,” Smithson wrote, “for 40 or more years people have tried to get oil out of this natural tar pool. Pumps coated with black stickiness rusted in the corrosive salt air.... This site gave evidence of a succession of man-made systems mired in abandoned hopes.” Ironically, as Dyer pointed out, the Dia Art Foundation organized a petition in 2008 to prevent Pearl Montana Exploration and Production from drilling boreholes in the lake to extract the oil.

The stewards of Smithson’s works have an awkward task: Spiral Jetty is supposed to be indeterminate and unfixed, responsive to the natural evolution of the environment — a drought hotspot that was immediately impacted by industry. Famously, the spiral was constructed when the water level of the lake was unusually low. When the water rose two years later, the rock coil went the way of Atlantis, and the work was still underwater when Dia began the process of acquiring it. But droughts caused the lake to recede and, in 2002, the spiral reemerged encrusted with white salt crystals. Today, the foundation collaborates with two organizations in Utah — Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College and the Utah Museum of Fine Arts at the University of Utah — to advocate for and protect the site by pursuing a course that aligns with the artist’s original intention. They say their mission is to preserve the work by documenting its changes: every spring and fall since 2012, a geospatial aerial photographer has captured images of the work.

Smithson understood that “pure science, like pure art, tends to view abstraction as independent of nature, there’s no accounting for change or the temporality of the mundane world. Abstraction rules in a void, pretending to be free of time.” The very premise of Spiral Jetty, then, is to reveal the changing climate. Drought brings the spiral into being, just as it is potentially the work’s — and the public’s — biggest threat.

Indeed, Smithson wrote of the inexorable extinction of humanity, finding in the grand narrative of entropy a kind of peace in eventual homogeneity. But we shouldn’t confuse this with equity. Of course, just as the “modern subject” looked specifically like a cis white man, the subject of Smithson’s entropic spiral is one conceived outside the constraints of social and economic factors. Entropy is here, it’s just not evenly distributed yet.

From Thomas Cole (himself an immigrant) to Barnett Newman, the American sublime has always assumed a sense of boundlessness — a free space in which the spectator might position himself. This presumption has persisted despite all the evidence to the contrary — be it an indigenous community or the women whose reproductive labor was required to support the colonization of the frontier. The void exists in the eye of the beholder. The painters of the 19th-century Hudson River School — Cole, Frederic Edwin Church, Asher B. Durand, and others — captured the wild stretches of the American East in crisp, dramatic light, creating the narrative of a young country ripe for entrepreneurial exploitation. Later, Hudson River painters such as Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran found the sublime in the west, amidst its diaphanous waterfalls and soaring mountains. These works were aspirational, propagandistic, and, in a way, they marked the demise of their subject, like death masks. The pictorial capture of these scenes meant that they were no longer pristine or infinitely available. Romanticism has always been laced with colonialism, machismo, and heroism — land art, as such, is no different. Let us not forget that to be present is sometimes to ignore the past and future.

IV.

On Saturday, August 29, 2015, I stalk the dusty dirt roads of a sparsely populated area of Joshua Tree National Park, an hour east of Palm Springs, and ninety minutes north of the storied Salton Sea. (In 1905, the Colorado River swelled and flooded a desert valley to form the largest lake in California, but by the 1970s, with no drainage or rainfall, nearby agricultural runoff had left it saltier than the Pacific Ocean; it remains a poisonous pool of decomposing wildlife.) I roll up to the ten acres of desert on which Noah Purifoy spent 15 years constructing the Joshua Tree Outdoor Museum. More than 100 architectural and sculptural assemblages weather on this plot of Mojave desert. The sky is completely unburdened and the sun scalds the sand, the metal of our seatbelts. Purifoy moved here from Los Angeles in 1989, at the age of 72, and dedicated his efforts to the museum until he died in 2004. Today, the site feels as optimistic in its resilience as it does melancholic, resigned to being refashioned by the focus of the sun and dust storms.

Purifoy’s neo-Dadaist constructions are made entirely from detritus he collected from his neighbors. They are mass-produced and industrial objects retooled to evoke his memories of the South (Purifoy was from Alabama) and the unmoored determination of westward-reaching colonialism. One configuration resembles empty bleachers, another, a church; there are ersatz covered wagons, locomotives, rollercoasters, an outhouse, a spaceship, and a repository for obsolescent technology. They are fragile monuments to an Americana conceived otherwise. I run between them to find refuge from the sun.

The museum’s arid site, its scale, and its use of materials from the surrounding environment link the project with the land art of twenty years prior. Like Smithson, Purifoy accepted that the work would submit to nature. “I don’t do maintenance. I do artwork,” he once said. “If it wants to deteriorate, I find some kind of gratification in watching nature participate in the creative process.” Although Purifoy’s museum is yet another carbon-intensive “destination” artwork, his contribution is distinct in that his materials reflect the social environment in which he worked. In that way, he addresses some of the failings of his predecessors. The work of land art proper engaged the specific objects of minimalism — the modules, blocks, and lines of Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris — which were understood to be specific because of their relationship to empiricism, for Judd, or gestalt, for Morris. In his definitive text on minimalist sculpture, Morris wrote that “simplicity of shape does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience. Unitary forms do not reduce relationships. They order them.”

Purifoy’s forms rather reject order, hierarchy, and structural frameworks, instead revealing the inequity that becomes visible as different materials are subjected to the same relentless conditions. One tire of four flattens, one plank on a façade rots, one bed frame rusts while another maintains its brassy sheen. As Huey Copeland recently wrote, “Purifoy’s entropy is one in which such endings are proliferating points of departure: the racial uprising, the social emergency, the ongoing disaster of western conquest and civilization are terminal cataclysms that are always arriving.” Rather than ceding to the abstraction of entropy, Purifoy’s work prompts visitors to observe that its effects are localized. His work brings into focus the ways in which social, economic, and environmental decay and transformation occur in specific and varied ways. The terminuses of entropy make way for un-encoded modes of being in, of, and with the world.

We often think of nature, and of the sublime, as something outside of us — as some inscrutable immensity that is overwhelming in part because of its disinterest to us, overcoming in its erasure of the observing self. But Lucy Lippard — the keenest early critic of post-conceptualism and land art, who later left the art world to become an environmental activist — makes a case for grounding such nebulous ideas of nature. In her 1997 book The Lure of the Local, Lippard parses the ways we produce and are produced by the landscape. She calls for localized responsibility that accounts for the extent to which personal decisions are embedded in the interests of global capitalism. The problem isn’t with seeking the sublime, she seems to say — we need those moments of reckoning. The problem is always seeking them elsewhere. Indeed, Rachel Carson would not have written Silent Spring, would not have sparked the environmental movement, were it not for her years in her rustic cottage on an island in Maine.

In his 1980 feature for Artforum, Walter De Maria wrote that “isolation is the essence of Land Art.” Suffice it to say, it is now untenable to conceive of the genre in that way. Earthworks are inseparable from the networks and infrastructures that protect and maintain them, that make them visible. They are dependent on the resources of those who commit to seeing them. They rely on airfare, car rentals, air conditioning — that is, on fossil fuels — at a time when an international, round-trip ticket causes the Arctic to lose three square meters of ice. Pilgrimages to land works necessarily involve an element of chance, a wager of time and investment. Is it worth the trip to Quemado if lightning doesn’t strike, to Mormon Mesa if we can’t find the unmarked road, to Rozel Point if the jetty is submerged? The pursuit of the works is as much the point as the work itself. The enigmatic directions, the spurning of technology, the sagebrush — these works exist as constellations of contingency, as irksome experience. The task now is to reconsider the scale of this worth.