No Enemies

by Jacob Dreyer

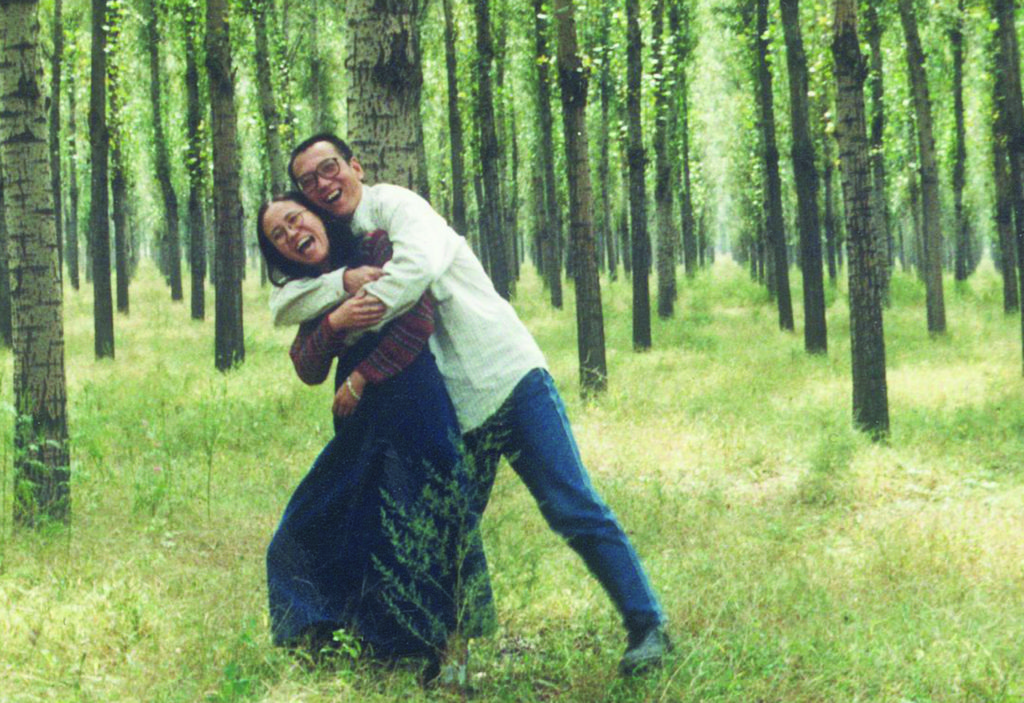

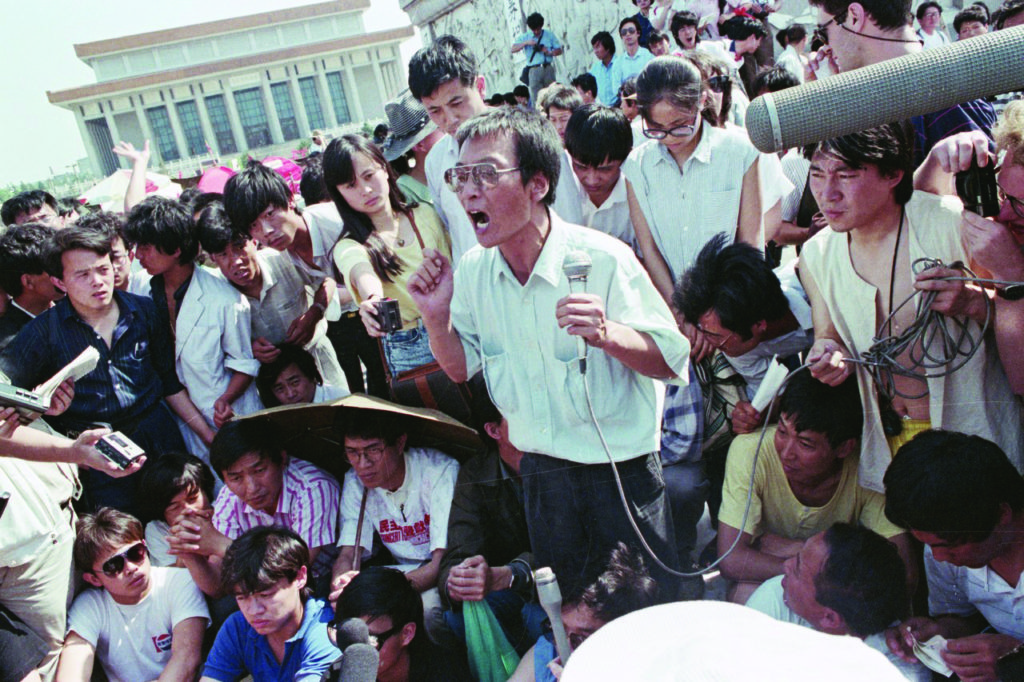

Students from Beijing's universities enter Tiananmen Square on May 4, 1989.

制度是死的,人是活的.

The system is dead, but the people are alive.

I.

Imagine, if you can, the following situation. You are a young intellectual: you’ve always had access to urban privileges, you’ve studied at a good university, and while you know that you have it better than some in society, you’ve chosen to devote yourself to culture. You want to be a writer, a philosopher, a painter, an activist; you want to use your privilege for the common good. You know that your country is fucked up, but you’ve watched changes in the past decade that seem remarkable. Changes so fast, in fact, that you’ve barely noticed that not everyone has been feeling as excited — the uncles, the grandpas, the country cousins.

Things start to come to a head, as two factions in the ruling classes, one more forward-looking and one more reactionary, become involved in an epic faceoff. Will the violence and nastiness of the past return, or will we finally put that behind us? Of course, you get involved. This is your chance to exorcise to the ghosts of history once and for all, to drive your country and society into a new and better version of itself. And you know that there’s no way the corrupt and nasty half will win out.

Much to your surprise, the unbelievable happens: your side loses. Your hopes are pricked like a bubble, and past mistakes (which at least were made sincerely back then) are reinstated in a cynical, gangsterish form. You have no idea what will come next. The media and universities are under attack. Friends talk about trying to emigrate, and when you look at relatives, neighbors, or even yourself, you feel unnerved. What the hell is this country you’re from anyway?

Such was the situation young Chinese intellectuals faced after June 4, 1989, the day 300,000 People’s Liberation Army soldiers and tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square in Beijing, firing bullets on hundreds of working-class Beijingers, students, writers, and artists who had spent six weeks demonstrating for democracy. Budding careers got thrown on different courses forever. Some left the country, and some changed their entire identities, as old meanings of “the state” and “the people,” the nation and the self, got shaken up.

If you search for “June 4” on Google here in China without a VPN, you won’t learn much about Tiananmen, nor about the intellectuals and artists who participated and ended up in exile or the grave. But the history of contemporary China — and of contemporary Chinese art, which now enjoys unprecedented international visibility, if not broad understanding — was set on a new path in 1989, and the course of events that followed has both local significance and global applicability. What did the protestors do next? What different strategies did they pursue to redeem their culture, to reinvent it, or simply to justify themselves?

I could give you 1.3 billion answers. There are as many Chinese cultures as there are Chinese people. But let’s limit ourselves to four men, and four models of speaking for the people when the state no longer does.

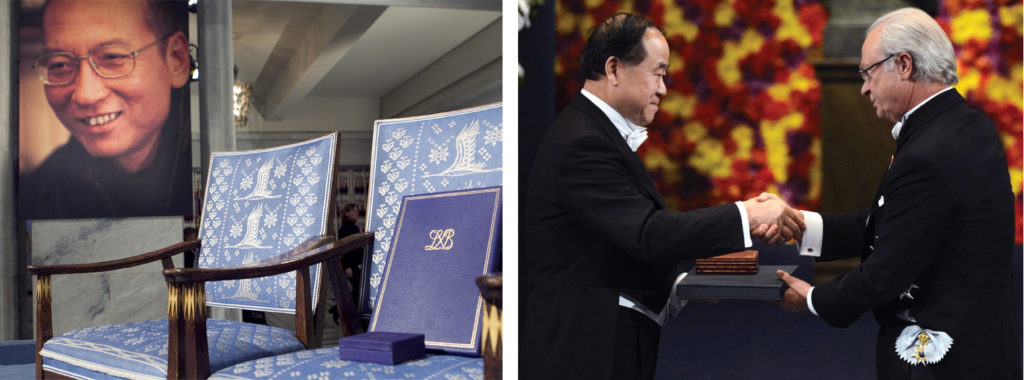

THE DISSIDENT

Liu Xiaobo’s death in captivity this year was an international disgrace, but the work of this poet, essayist, and rabble-rouser is remembered differently in China. He was the scion of a 1970s Communist leader, and a literary bad boy in the 1980s; his 1987 bestseller Criticism of the Choice, written while he was a Ph.D. student, captivated the intelligentsia. Liu’s life hinged around the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations — he flew back from New York to participate, went on a hunger strike, encouraged hundreds of students to withdraw before the tanks arrived, and then spent the next 20 years racked with guilt for not dying there. Although he spent a fair amount of this time making suicidal taunts to the power structure, his masterwork, for which he gained a Nobel Prize he could not collect, was the manifesto Charter 08. He proposed a bold set of reforms, calculated to be reasonable enough that even the placid middle classes could accept them, which was endorsed by hundreds of prominent individuals, Chinese and otherwise, in time for the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing. But if provocative gestures of rebellion are sometimes OK in China, plausible changes which threaten entrenched power are not. Liu drew comfort in prison from the love of his wife, Liu Xia, who is herself under house arrest. Maybe, just maybe, her love allowed him to die a happy man — one virtually unknown in the society he sought to change.

THE HIPSTER

Ai Weiwei is the world’s most famous Chinese artist, even as he is either unknown or, often, disliked in China. Ai grew up in the far-west Xinjiang province, where his poet father had been shipped off to a labor camp, and his formative years were spent exposed to the same tragic mix of idealism and brutality that befell so many during the Cultural Revolution. He made it back to the capital in time to be a member of Stars, the first recorded art collective in China’s contemporary history; he spent the 80s in New York’s East Village, honing his craft and hanging out with other Chinese hipsters, before returning to a traumatized post-Tiananmen Beijing. Chinese contemporary art as we know it emerged from the groups around Ai in the early 1990s; one was even called Beijing East Village, which tells you what you need to know about the youthful edginess Ai sought to encourage. Starting in the early 2000s, Ai increasingly butted against the leadership, and his exhibitions became more and more provocative; it probably didn’t help his cause that the provocations were broadly applauded in a west used to seeing China as a thuggish dictatorship. Whether or not the shoe fit, Ai was cast as the dissident artist, and, flattered by it, he kept going further on Twitter and in international shows. Perhaps he, like Liu and many others at the time, believed that the government would give way and liberalize. By 2008, that gig was effectively up.

THE EYEWITNESS

Mo Yan was a surprise Nobel laureate for literature; literature is hard to translate, especially from Chinese. But this country boy from a village in Shandong province has created an original body of work since the 1980s. Starting with Red Sorghum, a rural tale of sexuality and revolutionary chaos (which was adapted into a famous film by Zhang Yimou), Mo’s earthy work gained a large following abroad and, crucially, in China as well. Mo’s novels employ a perverse and vulgar magical realism; they feature cannibalistic officials, absurd massacres, and other not-so-thinly veiled allusions to the violence of China’s development, both before and after 1989. Mo’s fearlessness in using the Chinese language as it is, not as it should be, explains why his work stands as the archetypical literature of China’s “reform and opening,” as the era after the Cultural Revolution is called. Some internationally successful Asian novelists, such as Japan’s Kenzaburo Oe and Haruki Murakami, are accused of using “western” language, their grammar infused by foreign influence; not Mo. If you read his metaphors of the weather and the body, and his constant evocation of animals and plants, you may find that the one writer whose voice Mo’s most closely resembles is...Mao Zedong.

THE INSTITUTIONALIST

Xu Bing may be the least known of these four figures in the west; ironic, since he spent the most time in New York. A gentle and scholarly man, Xu grew up in Beijing, where his father was the head of Peking University’s history department. The “big character posters” of condemnation that were pasted across the campus during the Cultural Revolution stayed with Xu — and his later art, above all his monumental installation Book From the Sky, explores the peculiarity of Chinese characters, each one both an image and a word. After the massacre, he moved to New York and became Ai’s roommate; the two would collaborate on Wu Street (1993), a sly and sarcastic critique involving paintings found in the trash. He’d stay in New York for two decades, returning in 2008 to become a dean at China’s best art school. Xu went from artist to mentor; today, his work is primarily social and pedagogical in nature.

These four men and many others are united in “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World,” the years-in-the-making exhibition that opens on October 6 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. It is the most serious attempt yet by a major western institution to reckon with the cultural evolutions China has experienced since 1989, though it cuts off its narrative in 2008: the Olympian summer, followed by the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the autumn of western power. Even as these four lives advanced, in New York, in Beijing, in prison, in airport lounges and high-speed trains, China itself was transforming. The Communist Party shifted towards a purely illiberal technocracy, and spent 20 years being ruled by scientists, banishing Marx and Mao and then welcoming them back to win support for continued one-party rule. The face of the nation — the cities and the villages, the north and the south — changed completely. Your house, the food you eat, how tall your daughter is and how strong her teeth are, what color the sky is: these changed.

Today the government of the United States is explicitly geared around a conflict — economic, cultural, and we hope not ever military — with the seemingly petulant, truculent new hegemon that Xi Jinping’s China has become. What is China? A threat, an opportunity, a challenge? Is China Sylvia Plath’s Daddy, a boot in our collective face? Is it the chance to fix capitalism and also stop climate change? A collection of tanks rumbling down the boulevard, or a set of villagers who won the lottery wandering around in a daze? Whatever it is, China has now become something that the whole world has no choice but to understand. The interactions that Liu, Mo, Ai, and Xu spent their entire lives working out, the hinges between Chinese state and Chinese population, China’s future and China’s past, are all our business now.

II.

Chinese politicians often speak of the “century of humiliation,” by which they mean the era from the 1840s Opium Wars until 1949, when Mao stood atop the Gate of Heavenly Peace (or Tiananmen) and proclaimed a new People’s Republic. Those first decades of New China, broadly speaking, were a time of great optimism, when the flaws in the apparatus of the new state still appeared to be simply bad luck or accidents. Intellectuals were empowered as never before — the fathers of Liu Xiaobo, Xu Bing, and Ai Weiwei were all scholars and writers who worked directly for the state, even as they ran afoul of its infighting — and the notion that art should serve the people was a matter of life and death. Artists were constantly forced to confront the people; this was the dialectical part of dialectical materialism, and for many artists and writers during the Great Leap Forward, personal sacrifices were a minor concession to make for a new China whose full reality, stricken by famine and violence, they hardly knew.

The ultimate expression of the craving to end class divisions in China once and for all was the Cultural Revolution, arguably the most intense episode of mass psychosis that the world has ever known. Intellectuals, including pro-Communist intellectuals, were humiliated and beaten; landlords were killed, and in some cases cannibalism took place; buildings and cities were destroyed. Nothing was too sacred to interfere with. I won’t presume to describe the events here, but I will say that I’ve never had a close Chinese friend without a suicide in their immediate family. Liu, Ai, Mo, and Xu came of age during this chaos, and the core of their work has been to understand, dissect, and finally accept the Cultural Revolution, in whose wake China’s economy has grown from a peasant wreck into the world’s second, soon to be first, largest. “The culture we inherited was Mao’s adulteration of tradition,” Xu would later explain. “Whether it was good or bad is another question, but...this is what our generation was presented with. We can’t forget it or we would have nothing. We have had to identify ways in which to rethink it and use it.”

Our four positions were all born, one way or another, in the Year Zero of cultural revolution. Ai Weiwei spent the first 19 years of his life in camps in Heilongjiang and Xinjiang with his father, the poet Ai Qing, who was ordered to clean their village’s communal toilets for five years; Xu Bing, whose father headed the history department at Beijing’s best university, was sent down as well, albeit briefly; and Liu Xiaobo, whose father was a loyal Communist official, had the time of his life farming in Inner Mongolia. (Mo Yan, a son of farmers, experienced the Cultural Revolution — and the cultural elite more generally — as an outsider; he wasn’t sent down because he already was down, farming cattle in country Shandong.) Liu, Ai, and Xu were therefore heirs to a long Chinese tradition of aristocratic intellectuals whose opposition to privilege was to an extent a reflex of self-hatred, and whose advocacy for tearing down social hierarchies couldn’t really be extricated from their own privilege.

Ai and Xu returned home to Beijing after the death of Mao. Liu and Mo would both arrive to town in 1982. Their youth was an experience of the capital and the centrality of Deng Xiaoping’s state within it, mediated by elite educational institutions that were just emerging from ten years’ shuttering during the Cultural Revolution. They would encounter professors still cautious in word and deed — a caution which would engender impatience among the brash adolescents flowing into China’s 1980s, when these four figures produced their first works and tasted their first fame. Liu’s controversial essays on Chinese literature and society set off what the papers called a “Liu Xiaobo shockwave,” while Mo’s novel Red Sorghum established him as an author attuned to peasant sensibilities and raw sexuality, writing on a higher plane than the earlier genre of blunt fiction known as “scar literature.” Xu, who’d been bowled over by a Robert Rauschenberg exhibition at the National Art Museum (the first sanctioned show by an American artist after the reforms), began to fill books and scrolls with invented, meaningless Chinese characters, and Book From the Sky marked him as an iconoclast seeking ways to say the unsayable. Ai had moved to New York, but, as he would continue to do later, he meddled from afar. A crescendo of ambition, anger, and optimism started building. In Beijing’s northwestern Haidian district, on its university campuses, in the old city near the Bell and Drum Towers, on trips to the Fragrant Hills and to the beach, or to Shanghai, youths who saw their parents’ dreams get squashed started dreaming for themselves.

All four of the men we’ve discussed had their lives rent in pieces by an event in 1989 that only two of them were even there for. Created by Mao as a ceremonial platform for the people, Tiananmen Square had hosted mass gatherings in 1967 and 1978, public assemblies that saw citizens and the state face off over who truly represented China. By April 1989, when the liberal-minded Politburo member Hu Yaobang died of a sudden heart attack, young Beijingers’ dissatisfaction with the status quo reached a breaking point. They began to call for a free press, for an end to corruption. Tens of thousands showed up for the party leader’s state funeral on April 22, and five days later, in angry response to a dismissive People’s Daily editorial, even more students marched from their campuses and broke through the police lines around Tiananmen.

By May something like 300,000 people, most of them students, had assembled on the giant square that, if you think like a Chinese, sits in the middle of the world. Liu Xiaobo, watching from New York, saw his dreams coming true on his TV set. He was already skating on thin ice towards the end of the 1980s, with offhanded statements about the need for China to westernize; one might say his brashness was drawn out of a great pride, the paradoxical patriotism that manifests itself in criticizing what you love. He flew to Tokyo, then hesitated to catch his connecting flight, but headed onward to Beijing, and to what the party was calling a dongluan: turmoil. There must have been a feeling of destiny, or even an echo of the dreams of his father; in interviews from that time, the folksy, daring accent of China’s northeast marks his descriptions of the hunger strike he led. He described the hunger strike not as being heroic, but a gesture of repentance for cowardice. “We seek not death, but to live true lives,” began the declaration he and his fellow hunger strikers published on June 2. And it went on: “We have no enemies.”

All Beijing intellectuals were influenced by the movement in some way. Xu Bing was there, too, alongside his art students, who fabricated a 10-meter-tall papier-mâché statue they called the Goddess of Democracy. Ai Weiwei would join the hunger strike from New York, standing outside the United Nations and wearing a headband that read “Fuck Your Mother.” Mo Yan apparently fell into a depression for some time; his 1988 novel The Garlic Ballads was withdrawn from print, and his subsequent books turned even more bitter and sarcastic. But it was Liu Xiaobo, the most idealistic of the four, who found himself in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, when the army rumbled in. When the students were ready to die, he persuaded them to withdraw and convinced soldiers to hold their fire, saving an untold number of lives. Several hundred. Perhaps more.

As the sun rose over a new, punished Beijing, Liu hid out in an Australian diplomat’s apartment — a decision that would leave him tormented by guilt for decades to come, and that colored all his subsequent activism. By the end of the week he was in prison, denounced in state media as a “black hand,” but in a way, he never left that moment in the capital’s diplomatic quarter. Twenty years later, in court for the last time, he’d tell the judge that “June 4, 1989, has been the turning point of my life....” For Liu, June 4 was when literature was renamed politics.

III.

The 1990s saw our heroes redefining their work and their social roles in light of the new normal. Liu Xiaobo, bouncing in and out of jail and labor camps, thought of himself as a lone figure in the wilderness, as he alienated many of his peers with provocative statements about economic reform and American democracy. For every accolade Liu received in the west, he seemed to be punished more, and as the state simplified his complex thought into martyrdom, his fierce independent streak often led him into overreacting. (An example among many: he proposed that the Dalai Lama be named president of China.) The decades spent in small rooms, whether in jail or outside, seemed to pass without him noticing that his wilderness was blossoming into a new city, vibrant and vast, in which citizens expressed themselves in any number of ways. Through it all, Liu never grew cynical and always insisted on the possibility of sanity, dignity, and individuality in China. Coming from a person who had the sort of experiences in China that he did, that’s quite something.

Xu Bing moved to New York — by choice, though his formerly praised Book From the Sky was now being condemned as subversive. In America he continued, in his dignified way, to work through questions of reality and its representation, of image and word. The Chinese written language, a system of ideograms, is quite different from our own alphabetic system, and evocative in a way our poetry can never be. Xu made this his territory. Using the building blocks of Chinese characters known as radicals, he created thousands of new characters that were as meaningless as the lettered chart optometrists use to test your vision. Xu made use of these characters in printed books and flowing scrolls, but sometimes he indulged in bitter sarcasm: a 1994 performance featured rutting pigs with incoherent calligraphy on their hides. [A video of this work was set to appear in the Guggenheim’s exhibition, but was withdrawn days before the opening — as were two other works that rankled American animal lovers.]

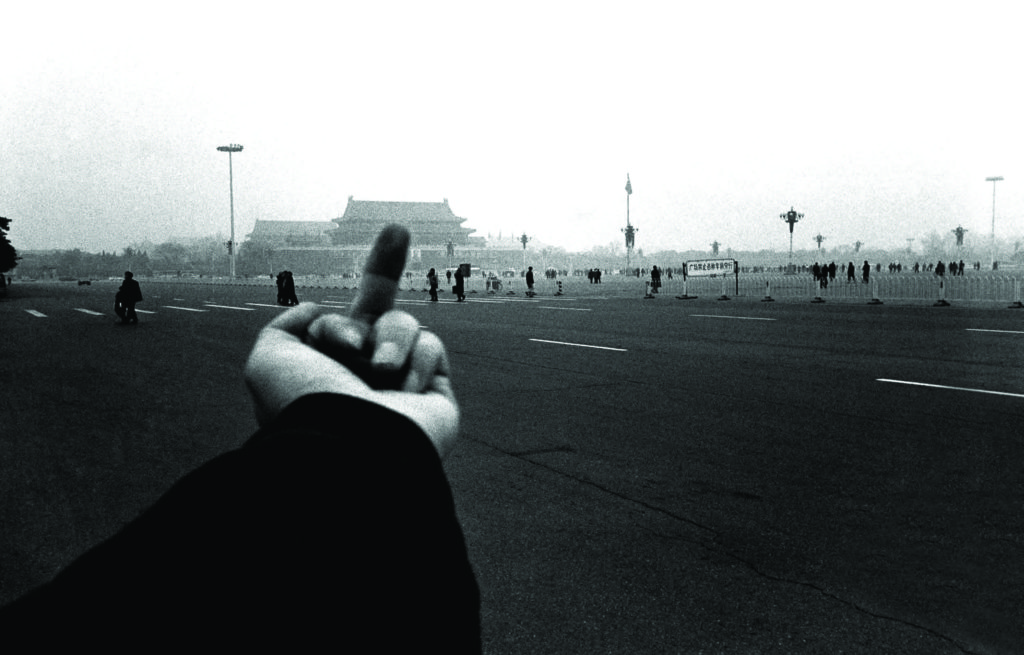

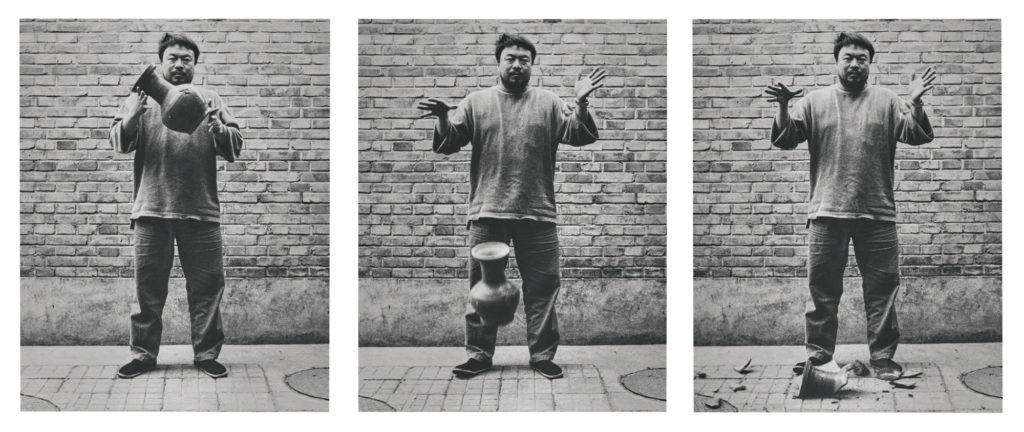

Ai Weiwei hung out with Xu in New York, and then returned to China in 1993. He found a new kind of freedom in Beijing’s East Village arts community, at least before gentrification pushed everyone further out to an area known as Caochangdi. From here he became a global celebrity, thanks largely to his facility streamlining the complexity of Chinese heritage for western consumption. His approach those years is exemplified by Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), a controversial photographic triptych in which he stares impassively at the camera and — well, drops a 2000-year-old urn. The gesture could be seen as iconoclastic or Duchampian; it also directly invokes the Cultural Revolution, as well as the entry of China into a global art market that prefers contemporary art to Han antiquities. He also took a series of photographs in which he gives the finger to political monuments; Tiananmen, the White House, the Eiffel Tower.... The specificity of his protest was sometimes a bit fuzzy in those years. But in popularizing Chinese visual tropes internationally, he became the ambassador for a new Beijing.

Mo Yan has the shortest Wikipedia page of the four men, but the longest one on Baidu Baike, China’s Wikipedia clone. Where Liu, Ai, and Xu often treated China in universalist terms, Mo spent his time recording local grievances and creating a mythology of the boom years, recounting the corruption of the 1990s in a string of novels often written quickly and carelessly. After Red Sorghum and The Garlic Ballads, he published a bawdy, baggy novel called The Republic of Wine, about an investigator named Mo Yan who discovers cannibalism and alcoholic orgies in a rural Chinese village. Scenes of disturbing excess are intermingled with philosophical musings, as when the narrator distinguishes himself from the character named “Mo Yan”: “I’m a hermit crab, and Mo Yan is the shell I’m occupying. Mo Yan is the rain gear that protects me from storms, a dog hide to ward off the chilled winds, a mask I wear to seduce girls from good families. There are times when I feel that this Mo Yan is a heavy burden, but I can’t seem to cast it off, just as a hermit crab cannot rid itself of its shell.” Liu was a prisoner of the state, doing time in a Dalian labor camp, but Mo was a prisoner of another kind: a prisoner of fate, whose only way out was to discard the self that manifested as a wall between his feelings and the world. How could they reach the Chinese people, in the years after Tiananmen? Liu thought he could do it by holding to unyielding principles; Mo did it by letting the self go, and getting into the dirt with everyone else.

These were heady times for Beijing, and the new millennium began as an era of high corruption and great freedom. It’s curious how those things go together, sometimes. The champagne bottles popped, even in the Great Hall of the People, when China entered the World Trade Organization. The Forbidden City was turned over to fashion parties. Liu Xiaobo was free — he ran PEN in China, apparently with the sanction of the government. Foreigners flooded in to teach English, or to run arts institutions. (Philip Tinari, co-curator of the Guggenheim show, came to Beijing in 2001 and never really left.) Rem Koolhaas got the go-ahead to build the donut-shaped headquarters of CCTV, the most impressive skyscraper of the age that just happened to be an agitprop studio; for some reason, God decided that the avant-garde Mandarin Oriental hotel next door should burn down in an explosion of fireworks on Chinese New Year. Ai Weiwei started blogging, and Liu called the internet “God’s gift to China”; much as it did elsewhere, the internet seemed to portend massive freedom until it became another, more comprehensive way to get spied upon. Xu Bing had been thinking of returning for years, and in 2008, he was named vice president of the Academy. “Now artists and the government are basically the same,” he told the New York Times that March. “All the artists and the government are both running with development.”

China was more open and free than ever before, possibly since the Tang Dynasty, or at least since the louche days of 1920s Shanghai. But far from the nightclubs and gallery openings, down in the coastal provinces of Fujian and Zhejiang, a well-born party official named Xi Jinping spent these years limbering up. None of the hip set in the Opposite House lobby bar, in the infamous clubs Punk, Haze, or White Rabbit, in the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, in the “seven-star” Pangu Hotel, knew it at that time, but the Chinese dream was about to be taken to ground, all in the name of the people.

IV.

The crest of a wave is when it begins to collapse. Ai’s pivotal moment, and the one which ended his career as an independent artist and began one as a full-on dissident, came in May 2008, when an 8.0-magnitude earthquake struck China’s central Sichuan province. It was a national tragedy, and the death toll of over 69,000 was made far worse by shoddy construction and corrupt inspection of “concrete” buildings that collapsed into powder. Ai and his team went out to Chengdu, collecting the names of dead children and posting them on his blog; in his art, Ai allowed the reality to speak for itself. For Straight, his team untangled thousands of tons of steel bars mangled by the quake; Remembering, on the façade of the Haus der Kunst in Munich, comprised 9,000 empty backpacks of children who died due to venality, graft, and hypocrisy. (On a later visit to Chengdu, Ai would be beaten so badly by the police that he suffered internal hemorrhaging.) Many resent Ai for his bombastic qualities, his narcissism, and his success. But in his most human moment, he threw everything away with righteous outrage at a system that sold the lives of children — the same cannibalistic tendencies Mo derided in The Republic of Wine.

This was the beginning of Ai’s end as an acceptable representative of the country. Three months later was China’s $44 billion coming-out party, the 2008 Summer Olympics — for which Ai had collaborated with Herzog & De Meuron on the stadium known as the Bird’s Nest. He ended up regretting it. For the opening ceremony China’s whole creative class, from the fireworks artist Cai Guo-Qiang to the filmmaker Zhang Yimou, was recruited to celebrate a “China” deeper than, but perhaps just as artificial as, the narrative of the party and the revolution. 56 representatives of the country’s 56 official ethnic groups danced in the Bird’s Nest, but all of them were actually Han Chinese. The diversity of China’s population and folkways, the depths of its history, the runic and enigmatic secrets locked into Chinese characters — Mao’s cultural revolution couldn’t destroy these things, but it seemed as if GDP growth could. The old China had been murdered, its carcass skinned, and at the Olympics those responsible turned that skin into a costume, using superficial cultural forms to mask the depth of change.

Liu wrote about the Olympics with the same acid pen he’d always brandished, mocking China’s “super-politicized, super-extravagant elite gold-medalism.” No doubt the state spectacle of the Games put fire into the document he worked on all that fall. He was not the initial author of Charter 08 — named after Charter 77, a human rights pledge of Czechoslovakian intellectuals during the Cold War — but he turned it into the first document of the Chinese middle-class dream. Where Tiananmen was an elite gathering in an elite place that revolved around elite concerns, Liu’s Charter 08 was written for a broad public, and made freely accessible online. It called for legislative elections and freedom of assembly, but also for the abolition of the hukou system, China’s de facto caste system that keeps urban and rural populations apart. It called for privatization of land, environmental protection, tax reform. Charter 08 wasn’t merely a lofty and abstract human rights plea, but a mature, measured, and realistic analogue to his activism of 20 years prior. It was a diagram that any small businessman could use to articulate his daily struggles. Not to die, but to live a true life.

Liu shared his Charter in the post-Olympics euphoria, perhaps hoping that the optimistic mood would allow the party the strength to reform itself. He was arrested immediately, as were dozens of other signatories. Liu’s crime was to create a democratic document, and the punishment was swift and brutal. Charged with “inciting subversion of state power,” he repeated what he had written in June 1989: that he had no enemies. He was sentenced to 11 years in jail, far longer than expected. Ai Weiwei was in the courtroom when the judgment was delivered. “Although this is a sentence on Liu Xiaobo alone,” he posted on Twitter, “it is also a slap on the face for everyone in China.”

It took a few days for the news from Oslo to reach him in the rural northeastern prison where he shared a cell with five other inmates, who may have also been spies. But Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Peace Prize was greeted with elation at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where students erected banners that were swiftly taken down. (One wonders if Xu spoke to the police as they came onto campus, and what he must have thought about the country he’d only just returned to.) The new tech companies were forced to censor information about Liu’s prize; there are “three T’s” of censorship in China, and Tiananmen is far more personal for Beijing’s new elite than Tibet or Taiwan. You couldn’t even search for the phrase “empty chair,” lest you discover that his Nobel diploma had to be awarded to a piece of furniture. In Beijing the prices of sushi rose faster than inflation, as Norwegian salmon exports experienced a post-Nobel trade blockade for years.

Ai Weiwei first heard about Liu’s Nobel while at Tate Modern in London, where he was installing Sunflower Seeds, his bed of millions of hand-painted porcelain ellipsoids, each individual yet apparently undifferentiated. (Like Chinese people, get it?) He had gotten away with far more than Liu, partly because his proposals were less serious, but soon his number came up too. The kompromat of Ai’s tangled personal life and messy finances became the excuses the state used to come down: he was detained for nearly three months, then accused of both tax evasion and bigamy. Xu had told the New Yorker earlier that “not everyone can be like Ai Weiwei, because then China wouldn’t be able to develop, right? But if China doesn’t permit a man like Ai Weiwei, well, then it has a problem.” It no longer permits Ai Weiwei, who now lives in Berlin.

And Mo Yan? It had been expected that the Chinese government would be enraged when he won the Nobel, as it had been for Liu Xiaobo. After all, Mo hadn’t written a single book that was complimentary to the regime as such; he’d exposed scandals on both the micro and macro level, and he’d helped to create a literature outside of the state — his earthy jokes being the antecedent to the internet slang and memes of today. Instead the Party treated him as a world-conquering hero, not least when he gave a shrewd no-comment to a journalist who asked about the Peace Prize laureate languishing in prison up north. (He later said he hoped Liu “can achieve freedom as soon as possible.”) When the state decided to like him, western critics immediately decided they disliked him, and Mo watched with a detachment that recalled his depersonalized “Mo Yan” character of two decades before. “The real target,” he observed, “was a person who had nothing to do with me. Like someone watching a play in a theater, I observed the performances around me.”

Right: Mo Yan receives the Nobel Literature Prize from the king of Sweden. 2012.

Meanwhile, apartments were built and torn down, millions of jobs lost, millions created. Protests flourished around the country; some, bourgeois in origin, got lots of attention and others, of workers against capital, got none. We now know that in the beginning of the 2010s, the top brass of the Politburo had urgent private discussions about what they saw as the impending collapse of the Communist Party, which could only be staved off by addressing corruption root and branch. Xi Jinping, who ascended to the top spot of the central committee in 2012, has since imposed extraordinary discipline, and he has brought down his rivals in a series of intrigues that has rivaled Shakespeare. Much like our artists, who claimed to speak for the people more authentically than the party-state could, Xi has used “the people” and their perceived benefit as the premise to eviscerate the state. (“Transforming the bones while retaining the carcass,” as the Chinese saying goes.) Xi too used a fantasy image of the west, the consumerist democracies whose model had proved so alluring to China, but Xi’s was a weaponized, demonized west: of wailing Hong Kongers denying Chinese babies milk, of arrogant and callow Americans, of decadent Europeans and of vile Japanese. That stance has been repaid a hundredfold, and he now rules the country with more personal authority than any leader since Deng Xiaoping. For Xi, the louche Beijing of the 2000s was corrupt; the champagne was corrupt, the parties were corrupt, and the notions of human rights and democracy were also corrupt. What was it being corrupted from, deviating from? The totalizing goal of transforming Chinese society, from which everything else is just a distraction. Xi and Mao have this in common: for them any art not in service of the people is not even really art.

This past June Liu Xiaobo was diagnosed with liver cancer. Though the authorities paroled him to a hospital, they denied him international medical treatment, perhaps because he could have received his Nobel from a German or American hospital bed. Calls for amnesty went unanswered, and when he died on July 13 the government supercharged the Great Firewall and forced his widow Liu Xia — the love of his life and addressee of his aching prison poetry, who has been subject to house arrest since the Nobel ceremony — to scatter his ashes at sea. (Ai Weiwei, tweeting from Berlin: “Inhuman, insult, shameful, disgusting....”) The American media, who by now thought that the real threat to their country was not in Beijing but Washington, did not make such a big deal out of Liu’s death; few of those who did were mature enough to pay Liu the tribute of respecting the Chinese people as much as he had. While the politics of elite power struggles and macho grandstanding consumed Liu’s youth, towards the end of his life he reached calm, humility, realism about the fate of ordinary citizens, and a deep, beautiful love. How do you think we should honor his name? Like the fanatic senator “Lyin’” Ted Cruz wants — by renaming the street outside China’s DC embassy Liu Xiaobo Plaza? Liu’s work cannot be made into a weapon against the Chinese people, or for violence. He had no enemies, after all.

V.

The first generation of modern Chinese intellectuals, from Xiao Hong to Lu Xun to Mao Dun, found it extremely difficult to reconcile the Chinese cultural tradition — essentially a gentry tradition, understood and consumed by just 1% of the population — with Enlightenment notions of social equality. The intellectuals who would be heir to Chinese civilization’s patrimony are heir to perhaps the greatest of all human traditions, but also to a history of violence, and, as Mao said, “a society which treats 97% of humans as livestock.” As children of intelligentsia families living in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen, Liu, Ai, and Xu are something like the children of Holocaust survivors — that is, if those children were tasked with reinventing a national culture when hundreds of millions of people, even many of the victims, didn’t think the dark years were all that bad. This may be why the only categories of Chinese people who drink heavily are government officials, artists, and peasants.

All four of these men represent different ways of coping with the opposition between China’s state and China’s people, between structures of power on one hand and the land and traditions they control on the other. Liu Xiaobo said everything, and for his trouble almost no one in China heard him. Ai Weiwei said almost as much, though later he spoke principally to audiences beyond China’s borders; Xu Bing pushed the limits of China’s classical tradition, but not so far that they snapped. Mo Yan chose to be silent on certain topics, even while fiercely voicing the life of the people decade after decade. (Even his pen name is an act of reticence: mo yan, in Mandarin, means “don’t speak.”) He put the true experience of postwar China, which includes Maoism, the Cultural Revolution, pettiness, violence, and sex, before the political tasks of the moment — for which he netted both a Nobel of his own and immense western condemnation.

Lust, caution. Is it better to be part of the system? Is it legitimate to collude with a system that commits human rights abuses, even in an attempt to improve it? If not, what are writers and artists doing in the United States, or for that matter operating within the capitalist system at all? I myself made the choice to live and work in China, cognizant of the imperfect nature of the government whose strictures I would have to obey. I don’t quite grasp why this is so appalling to some people, while moving to the United States, a state that also commits abuses against nationals and foreigners at a vast rate, is somehow OK. But perhaps I am also hypocritical, in ways that I cannot understand. Perhaps the Chinese artists forced into compromises that appear unsavory to the outside world also did so inadvertently, walking down the path of good intentions.

Not long ago I traveled to Yan’an, the birthplace of Mao’s revolution, far from the lights of Beijing and Shanghai. The place is desperately poor. There’s no high speed rail station, and the nearest Starbucks is 300 kilometers away. Here, in the spring of 1942, Mao Zedong declared that art must serve the people — a principle that became a grenade during the Cultural Revolution, that Deng Xiaoping would afterwards renounce, and that Xi Jinping has lately brought back into currency.

“In the last analysis, what is the source of all literature and art?” asked Mao at Yan’an. “The life of the people is always a mine of the raw materials for literature and art, materials in their natural form, materials that are crude, but most vital, rich and fundamental. They make all literature and art seem pallid by comparison. They provide literature and art with an inexhaustible source, their only source. They are the only source, for there can be no other.”

To be an artist or writer of the greatest prominence in China today, it would seem that you must accept this old Maoist principle, or at least pay lip service to it. Mo Yan certainly has. But Liu Xiaobo too, in his essays and poems and Charter 08, also mined the life of the people — above all, the people who died in Tiananmen Square in 1989, whom he eulogized from a labor camp as “that bone-devouring memory / best expressed / by refusal.” Mao thought art could serve the people only in a single prescribed fashion, but you can serve the people thousands of ways, through fiction or polemic, by dropping urns or writing calligraphy, by railing against the state or making peace with it. You can serve with a clean heart, locked in a cell, or with an infected one, soaking in corruption and compromises. But somehow you must find your way through the muck of the state, past the ghost of the self, and all the way to the people. Their lives are the only source of your work, and there can be no other.