The People’s Choice

by Zoë Lescaze

One hundred years ago, the Russian revolution sent art history charging down a new track — but who now commemorates it? Three exhibitions in three cities reveal the art of a Soviet century, and the long journey from the Finland Station to Trump Tower

Left: El Lissitsky. Record. 1926. Gelatin silver print. 10½ × 8¾ in. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Right: Gustav Klutsis. Memorial to Foreign Leaders. 1927. Book cover with lithographed photomontage. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In the years following the Russian Revolution, no object was too small, domestic, or banal to serve as an agent of radical influence. When the Bolsheviks seized control of the Imperial Porcelain Factory in 1917, they hung onto the fine china intended for the tsar. Instead of smashing the whiteware to bits in a rousing denunciation of bourgeois extravagance — sic semper saucers — they saw an opportunity, a chance to scrap the boundaries between art and everyday life. They invited leading abstract painters who fervently believed their work could galvanize the masses to emblazon the blank vessels with bold new designs. Theirs would be a world in which ideology infiltrated physical reality, where utopian philosophy found concrete form. The proletariat was to be inspired, directly, by crockery.

A century later, the ideological zeal of the avant-garde feels profoundly alien and, given the fate of communism, tragically deluded. The Museum of Modern Art in New York recently mounted an exhibition that plunged viewers into this heady period of invention and ill-fated idealism — which, for many westerners, is essentially where Russian art history ends. Radical innovation, however, did not disappear when Stalin stomped his jackboot on abstraction in 1934, as affirmed by two other exhibitions this year marking the centennial of the Russian Revolution. The Centre Pompidou in Paris showcased underground practices that proliferated at the margins of later Soviet society, undercutting the state-sanctioned paintings of gung-ho steelworkers and noble state officials we all know and loathe. Meanwhile, in Moscow, the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art launched the first Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art, shining a light on a diverse group of artists from across this giant country.

These exhibitions came at a crucial moment. Western views of Russia have hardened since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and, especially since the election of Donald Trump, Russia has resumed its status as the United States’s number one bogeyman. “Sinister” is the word many Americans use to describe the rival nation. And Russia is sinister. Civil rights and free speech are violently suppressed; distinctions between church and state are rapidly dissolving, to the detriment of minority groups. Domestic violence was recently decriminalized. Gay rights are nonexistent. In Moscow, Stalin impersonators busking in the shadow of the Kremlin testify to an incomprehensible but pervasive nostalgia for the harshest years of the Soviet era. It’s an unsettling spectacle — imagine seeing Hitler doppelgängers hanging around Alexanderplatz — that evinces a pernicious cultural amnesia. But the exhibitions in Paris and Moscow revealed other currents of the Soviet century, and revealed too the changing role of artists in a nation where culture has always had an immediate relationship to power.

At MoMA, “A Revolutionary Impulse” explored the artistic activity that flourished between the early 1910s and 1934 through 250 works from all of its stubbornly cloistered departments. The show united iconic paintings by Kazimir Malevich, films, photographs, ads, architectural models, children’s books, and socialist swag, such as the enamel pins Aleksandr Rodchenko designed for the first Soviet airline. And, of course, those teacups, branded with red rectangles and black squares.

These relics of the Russian avant-garde radiated a heady self-confidence and infectiously fierce conviction. The artists working in the aftermath of the revolution had a mission, and they operated with an entirely different concept of success than critical approval or market profitability. If some objects — the airline pins or porcelain, for instance — sound silly or naively self-important, they assumed a defiant dignity when surrounded by masterworks forged in the same ideological fire. Their self-assurance was at once magnetic and wholly foreign.

In this new schema, the artist would not merely depict the world as it was, but be “a builder of a new world of forms, a new world of objects,” according to El Lissitzky, a prolific draftsman, painter, and printmaker prominently featured in the exhibition. His triumphant, handwritten manifesto accompanied a rare set of lithographs from 1920 that reflect both his architectural training and revolutionary temper. Rectangular beams, fine lines, arcs, and planes soar diagonally through space, converging in restless compositions that evoke assembly guides for unbuildable, utopian structures.

And yet, even as Lissitzky and his fellow artists were dreaming up a new world, Lenin was taking brutal steps to strangle its infant idealistic ethos. Lenin purged rural populations and waged a bloody civil war that left more than seven million people dead. The devastation, of course, only worsened under Stalin. The poignancy of these masterpieces and minor artifacts of the Russian avant-garde is indelibly tied to this disconnect between art and atrocity. Their power, however, transcends tragic irony; they are moving because we no longer believe in the radical potential of abstract prints and paintings, let alone teacups. In our politically fractured world, this conviction would be a comfort.

Non-Russians have the luxury of gazing at these objects through a wistful scrim, but artists who directly experienced the aftermath of the revolution have a less nostalgic view. Long before the Kremlin lowered the red flag in 1991, underground Soviet artists were examining the ideological zeal of their forebears with varying degrees of arch humor, mockery, and mordant disdain as they struggled to work amid censorship and persecution. These so-called “unofficial” practices were the focus of “Kollektsia!,” a shambolic but edifying exhibition at the Pompidou. The show, which featured several hundred recent gifts from Russian collections, both shaded the celebratory presentations of the early avant-garde and offered a vital corrective to widespread western ignorance of the Soviet underground. For many of the artists on display, mining the revolutionary past was a means of critiquing and coming to terms with the present.

The 1970s and 1980s yielded particularly caustic reflections on socialist ideology. With A Catalog of Superobjects: Supercomfort for Superpeople (1976–77) a brilliantly sardonic set of 35 photographs and texts, the conceptual duo Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid satirized western consumerism (the whole project is modeled on a Sears Roebuck catalog), but they really were skewering socialist efforts to draft ho-hum household objects into their revolutionary crusade. In one photograph, a woman stares brightly off into space, modeling what looks like a metal oven rack on her head. The device is guaranteed to “protect the purity of your thoughts” and prevent “mass hypnosis.”

Other Soviet artists responded with less subtlety to the optimism of the revolutionaries and bleak realities of the Stagnation Period, the barren years between the reign of Khrushchev and the start of perestroika. The Last Supper (1989), an installation by Andrei Filippov, consisted of a long table, draped in red cloth and set with 13 plates, each flanked by a hammer and sickle instead of cutlery. (Judy Chicago for the bitter Soviet set.) Above the table, a sculpture by Leonid Sokov entitled Glasses for Every Soviet Citizen (1976) hung from the ceiling. A colossal pair of wooden spectacles with stars cut in the red lenses, the piece made its point almost as heavy-handedly as the propaganda it challenged.

The most nuanced projects in the exhibition were often the easiest to miss. Small black-and-white photographs — documentation of the happenings that Andrei Monastyrski and other members of the Collective Actions group enacted in the late 1970s — hung quietly in one corner. The pictures of people standing around barren, nondescript fields do not scream for attention, and that’s kind of the point. While Khrushchev is known for ending the purges and relaxing social policies, he maintained his predecessor’s ban on abstract art. It was difficult for “unofficial” artists to buy art supplies and illegal for them to exhibit their work. Retribution was swift, and sometimes brutal, for those who defied the censors. Various “Kollektsia!” artists were exiled or drafted into military service. Others died under mysterious circumstances. In response, the Moscow Conceptualists created coded images and ephemeral, inconspicuous projects. Monastyrski and his collaborators would invite small groups of friends to meet them at appointed times in rural locations. Simple inscrutable actions — the artists walking across a field — would unfold. Everyone would go home and record their impressions. These seemingly spare occurrences offered a discreet but vital alternative to official public life in Moscow, as the art historian Claire Bishop has noted, by encouraging free thinking and subjective interpretation. Given the deliberately cryptic nature of these and other works, the Pompidou curators could have done more to illuminate their content. For non-Russians, the most legible projects were those that directly engaged socialist iconography.

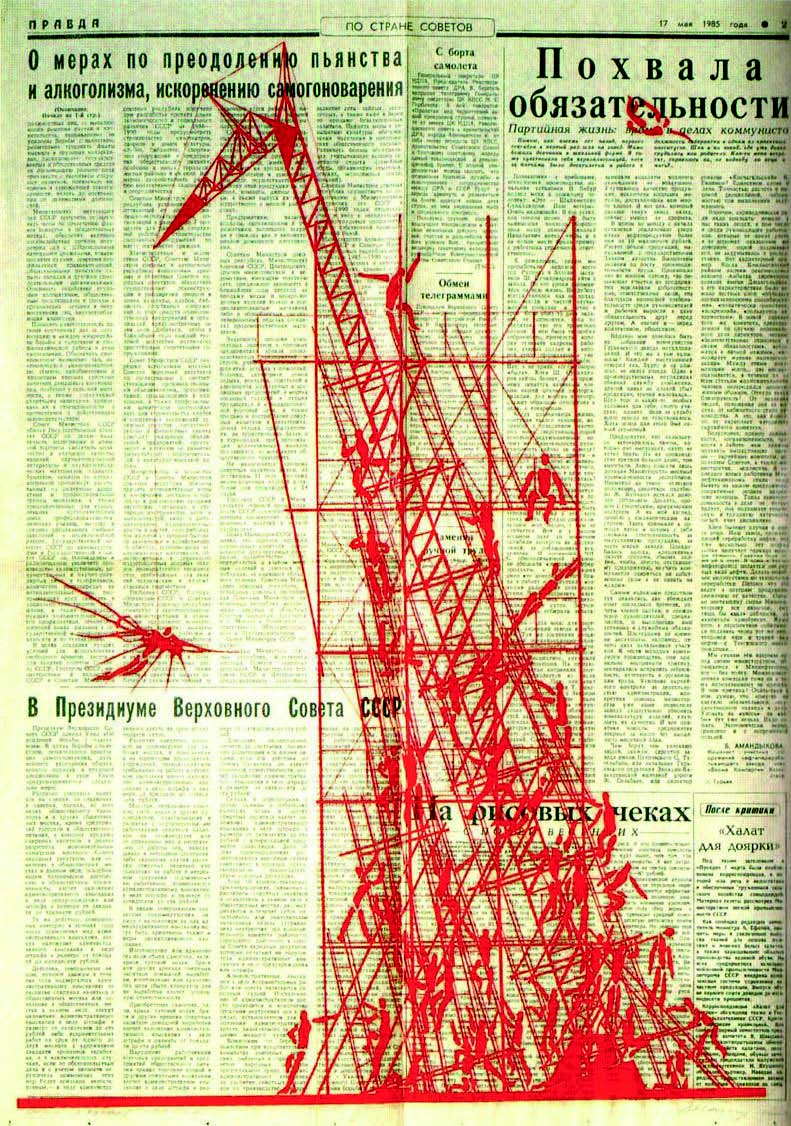

Red Tower (Homage to Vladimir Tatlin), a print by Yuri Avvakumov from 1986/89, riffed on one of the most potent symbols of the revolution: Tatlin’s Tower. The structure, formally entitled Monument to the Third International, was designed to house the global headquarters of Communism in 1919. It was a wildly ambitious project: glass geometric shapes, each containing different state departments, that would spin at different speeds within a vertiginous steel exoskeleton. Never built, needless to add. The structure became an emblem of the revolutionary period and its utopian ideals precisely because it was not realized.

In Avvakumov’s Homage, red figures scramble madly up a rickety jumble of ladders resembling the Tower. One winged figure glides to the left of the listing structure — an allusion to Tatlin’s subsequent designs for flying machines — while another plummets toward the earth, hammering home the Icarian overtones of Tatlin’s work and the whole communist project. Avvakumov provides a deadpan caption for the image, presenting the print as though it were a serious architectural proposal:“an installation of scaffolding and fire escapes for risk-free testing of manned flying devices [in] Gorky Park.”

Recently, that same park was the site of a different kind of experiment — one that could easily have fallen flat, given its own unwieldy ambitions. The first Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art was a dizzyingly eclectic exhibition of 68 artists from major cities and minuscule towns. The Garage curators chose not to impose a theme on the exhibition, which resulted in a bewildering assortment of work; navigating the museum felt a little like being inside an opera house in which every member of the orchestra was independently sawing away at his instrument while every diva belted out her favorite aria. But for international visitors who came to Moscow with a carry-on bag full of contemporary Russian stereotypes, the wide array was a remedial course in the country’s diversity and cultural sophistication. The works at Garage did not reflect caviar-guzzling oligarchs, businessmen flaunting a Rolex on one wrist and pneumatic blonde on the other (although more than a few of those characters were at the vernissage, chatting with the museum’s billionaire founders Dasha Zhukova and Roman Abramovich). Instead, the projects on view attested to the many other faces of the country, fittingly gathered in a city whose local art scene is exceptionally warm and welcoming to outsiders.

A preoccupation with Russia’s tumultuous history united a striking number of works. Artists offered up somber allusions to the traumas of the Soviet period, playful jabs at its more absurd elements, and elliptical considerations of collective memory and its mutability. Sasha Pirogova choreographed a video around Soviet bread lines; Anastasia Bogomolova photographed the forbidding site of a former gulag. Certain works made such specific references to Soviet culture that they were incomprehensible to foreigners like me. One painting by Damir Muratov, for instance, played on the lyrics of a Soviet song (“Hope, my earthly compass”) with the line “Hope is our earthly complex.” That the phrase was also a pun on “Oedipus complex” suggests a certain love-hate relationship with the past and with Soviet nostalgia. No shortage of other projects — especially those involving found objects and ephemera — simply alluded to the past, or offered up its flotsam without probing it.

It isn’t surprising that, in a society that has undergone two wholesale reinventions within a century, artists are fixated on this fraught history. Access Point (2016), a meditative installation by Dmitry Bulatov, was one of the most compelling works in this vein. A cylindrical mirror jutted from a hexagonal platform, along with patches of living grass, and a strange web of branching gray plastic resembling a reef of sci-fi coral. Reflected in the mirror, the skewed skeletal lattice resolved into Tatlin’s Tower, distortions corrected by the curvature. Nearby, Bulatov projected a digital rendering of the Tower as it would look in modern-day Saint Petersburg. Its quality was connected to the grass via sensors; if the museum neglected the plants, the image would disintegrate. Our view of history, Bulatov suggests, changes depending on our vantage point and on how conscientiously we work to maintain clarity, to correct distortions.

Bulatov’s installation on memory and its mutations comes at a moment when history has begun to repeat itself. Censorship abounds in Russia. Journalists and dissidents disappear, politicians are shot in broad daylight, and certain artists, most famously the women of Pussy Riot, have been imprisoned. In this climate, the Triennial curators made an admirable decision to devote a section of the exhibition to progressive, explicitly political works addressing gender equality and homophobia, among other issues. Urbanfeminism, a project by Uliana Bychenkova and Alexandra Talavera concerning Russian women and people with nontraditional sexual and gender identities, consisted of pink and purple zines visitors could take home. Because the distribution of so-called LGBT “propaganda” to minors is illegal, the area was off limits to viewers under 18.

That the “Art in Action” section existed at all was significant for local audiences — work like this is rarely found in the country’s major museums — and for international viewers disturbed by the real and imagined specters of Russia. For them, political projects like these offer reassuring evidence that the country is not one big Putin fan club. The irony is that Americans, who may benefit most seeing contemporary Russian art, rarely encounter it. Russian censors prevent certain works (ones with gay content, for instance) from leaving the country, and a mutual embargo on loans between US and Russian museums means that major works and exhibitions cannot travel. One piece in the Triennial spoke eloquently to this dilemma; fittingly, it was not inside the museum. Kirill Lebedev opted to paint a mural on the Garage curatorial offices, reading, in big, bright letters: “Thank you for your attention and your attempts at comprehension.” The artwork seemed intended to speak for the curators inside — a message to the art world jetset as much as the Moscow public. Tellingly, the mural did not thank viewers for understanding. It thanked them for making the effort at all.