House of Treasures

by Max Nelson

Julianne Moore’s perfect housewife, Kate Winslet’s striving entrepreneur, Cate Blanchett’s mannerly mondaine: the heroines of Todd Haynes’s movies are curators of domestic space, their homes on permanent view. Now Wonderstruck, his kid-friendly new movie, takes place in an actual museum: New York’s Museum of Natural History, which offers a home of another kind to three lost children. For Haynes, today’s greatest exponent of American melodrama, everything hinges on the rules of display.

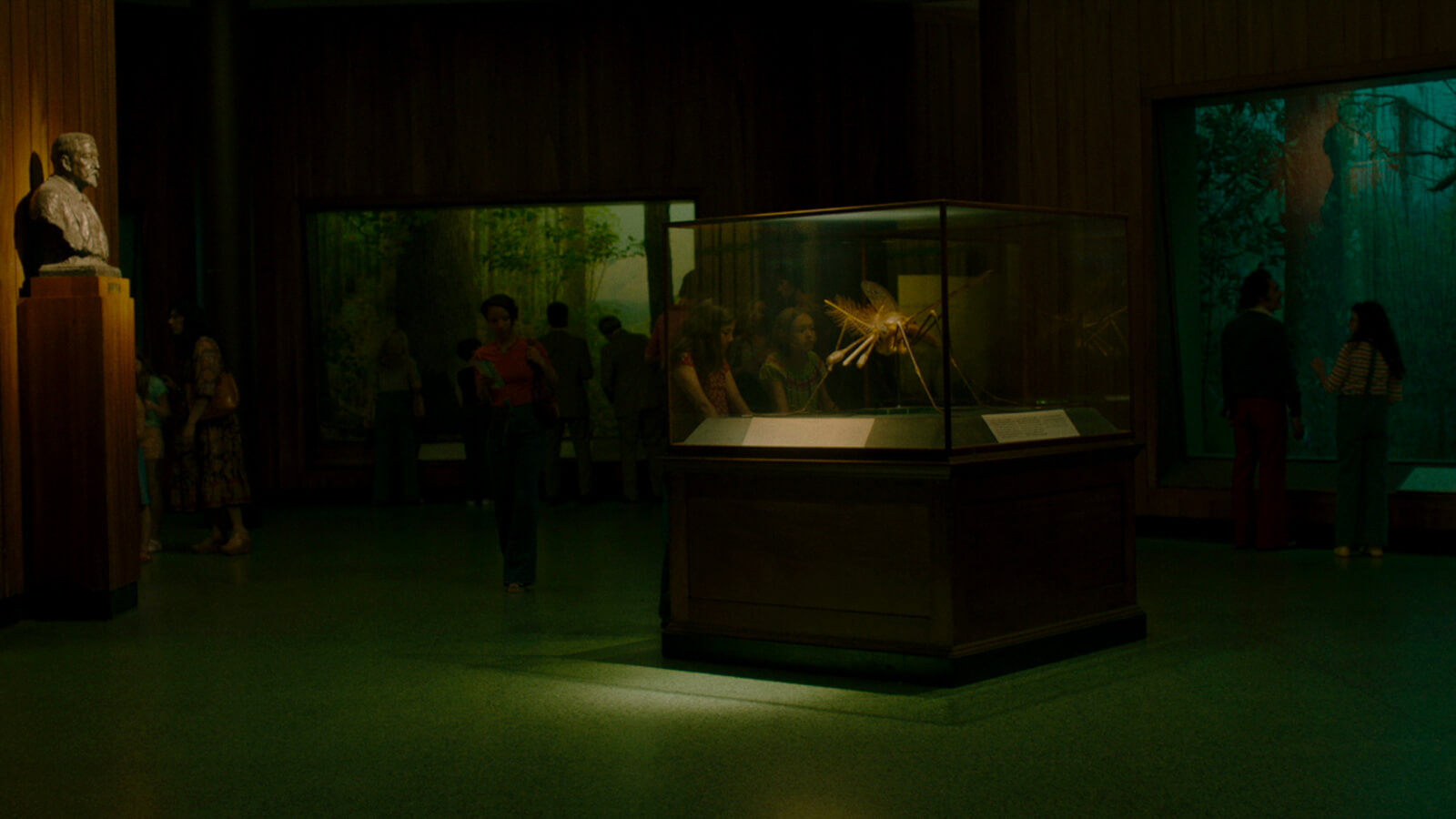

Todd Haynes. Wonderstruck. 2017. Feature film. 115 minutes. Photo: Mary Cybulski. Courtesy Amazon Studios and Roadside Attractions.

I.

Late in Mildred Pierce, the miniseries Todd Haynes adapted in 2011 from James M. Cain’s novel about several tragic years in the life of a Depression-era businesswoman, the heroine’s rakish new husband Monty sits her down for what he calls a “lesson in interior decorating.” The couple — played in the series by Kate Winslet and Guy Pearce — have just moved into an enormous Pasadena mansion that had belonged to Monty’s family: a financially ruinous attempt on Mildred’s part to win the approval of her scornful, class-conscious daughter. “A home isn’t meant to be a museum,” Monty tells her as he shows her through a room he’s decorated with paraphernalia from her restaurant business," filled with Picasso paintings or Oriental rugs like this place used to be. It’s meant to be furnished with things that actually matter.” In the novel, his speech goes on: “If they’re just phonies, bought in a hurry to fill up, it’ll look like that living room over there, or the way this lawn looked when my father got through showing how much money he had.”

By this point in the series, we know not to take such pleas for authenticity at face value. Mildred, we’ve realized, is using her new husband’s charm and society credentials to lure her daughter back; he meanwhile relies on her for money and trusts that she’ll get him, too, closer to her daughter, on whom he has his own designs. Monty’s speech might seem a sincere repudiation of “phony,” reputation-conscious home design, but in fact it’s something of a fake itself — a move in a complex game of feints and ironic concealments. What, then, is a real home? What is a phony one? What does it look like to furnish one’s house with “things that actually matter,” rather than, say, with things “showing how much money” you have? What is it that goes wrong once a house becomes a museum?

Much of Haynes’s new film Wonderstruck, which premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and opens in the United States this October, takes place in an actual museum: the American Museum of Natural History in New York, through which the children at the center of the movie wander looking for a home. The business of separating real homes from ones on display has preoccupied Haynes — an ingenious contriver of melodramas, domestic tragedies, and movies about the ironies of show business — since the start of his career. He was born in 1961 and raised in Los Angeles. His maternal grandfather had been the head of set construction at Warner Brothers, where, as Haynes once reported, “he was a union organizer and close to many of the blacklisted figures in mid-century Hollywood.” The same grandfather would later help fund Haynes’s first feature, Poison (1991), a triptych of Jean Genet-inspired stories whose frank studies of sex among male prison inmates made it the subject of a foolish but heated national controversy and put it at the center of what would become known a year later as the New Queer Cinema.

By that point, Haynes had won a reputation not only for prodigious talent but also for a certain de ance. He had made his first short, a psychodrama about a disaffected young boy called The Suicide (1978), in his second year of high school; straight out of Brown, he co-founded Apparatus Films, an influential production company, and served as an original member of Gran Fury, the AIDS activism artist collective that worked in tandem with ACT UP. Soon thereafter he circulated, in violation of a legal order, his grim Karen Carpenter portrait Superstar (1988), in which Barbie figurines reenacted the singer’s decline into anorexia from the inside of a dollhouse that eerily resembles the standardized mansions we find in later Haynes films like Safe (1995) and Far From Heaven (2002).

The films Haynes has made since that early start — four shorts and mid-length movies, the miniseries Mildred Pierce, and seven features — almost all turn on how people organize their living spaces to condition what they want or keep themselves from wanting what they think they shouldn’t. Carol (Julianne Moore), the self-identified “homemaker” at the center of Safe, rejects a black sofa set for the living room she’s decorating because it “doesn’t go with anything”; soon she develops a violent allergy to her home, as if it’s been rendered so impeccable that she no longer goes with it herself. Cathy, the married woman Moore plays in Haynes’s lush 1950s period piece Far From Heaven, finds herself estranged from the trimmed perfection of her suburban home by her love for one of the figures she’s hired to maintain it: her African-American gardener Ray (Dennis Haysbert). Similar limits affect the two women at the center of Carol (2015), one of whom lives in her estranged husband’s New Jersey mansion; they only act on their love in anonymous rented rooms. In these films, as in Mildred Pierce and now in Wonderstruck, curtains, chairs, beds, and wall hangings are forms of control, making themselves felt for their power to set the tone and boundaries of a space.

Such homes put checks on what people can hope for. Their forbidding décor warns their inhabitants against any moves that might make a mess of one’s reputation or prospects. Those warnings tend to fall with particular force on women and on children with unruly or unwelcome desires. The preteen boys who populate Haynes’s earlier movies respond to “phony” living situations with still deeper excursions into fantasy or unreality. One, in Dottie Gets Spanked (1993), retreats from his bland, conventional suburban home by obsessively drawing the childlike woman at the center of a TV show modeled after I Love Lucy. We first see the hero of Velvet Goldmine (1998), who eventually rises to fame as an androgynous glam-rock star, as a young boy surreptitiously putting on lipstick.

No two films of Haynes’s look quite alike. The vivid colors and frenzied cutting of The Suicide evolved into the glorious clutter of Poison, which fits back and forth between the styles of a black-and-white 50s monster movie, a TV docudrama, and an opulent erotic fantasy. The tense precision of Safe bloomed into the rich, Technicolor stylization of Far From Heaven; the David Bowie tribute Velvet Goldmine and the fractured Bob Dylan biopic I’m Not There (2007), with their nervy editing and swaggering atmospheres, gave way to the handsome, immersive textures of Mildred Pierce and Carol. What Haynes’s films have always shared, however, is an animating tension between the elements that stabilize a given movie — meticulous set design, judicious compositions — and those that shake it up: a cut that falls off-beat; an actor who moves out of step; a musical cue that breaks in unexpectedly. Just as the women and children in these films can’t take to the manicured settings they inhabit, so the movies themselves seem to rebel against the styles they’ve been assigned.

Velvet Goldmine opens with a prologue, set in 1860s Dublin, of the young Oscar Wilde in school. (His teacher asks him what he wants to be when he grows up. “A pop idol,” he says.) Wonderstruck too begins with a tribute to Wilde. In its first minutes we see that Ben (Oakes Fegley), the 12-year-old boy who emerges as the movie’s central character, has a quote from Lady Windermere’s Fan pinned to the wall of his Midwestern bedroom: “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” He got the line from his mother (Michelle Williams), and it becomes something like a slogan for the film he moves through.

That the film deploys Wilde’s epigram more or less literally — as an aspirational motto urging Ben to solve the mystery of his absent father’s identity and make a better life for himself — is in keeping with its overall tone. This is a mellow movie in which layers of suggestion, atmosphere, and period texture overlap like curtains over screens, enveloping the action in a mood of missed satisfactions and melancholic hopes. (Wonderstruck is the first of Haynes’s movies that could plausibly not be lost on child viewers; it was adapted from Brian Selznick’s bestselling “novel in words and pictures,” to borrow the book’s subtitle.) It leaves little room for irony and rarely permits the tensions that animated and complicated Haynes’s earlier films. You would never know from watching Wonderstruck that when Lord Darlington delivers that line in Lady Windermere’s Fan, his addressee gives a wry exclamation and tells him that he’s being “very romantic to-night.”

II.

Wonderstruck has two parallel plots, set — initially — 50 years apart. Both introduce us to deaf preadolescent children living in inhospitable homes. In 1927, a girl named Rose (Millicent Simmonds, a deaf child actor appearing in her first movie) grows up in a Hoboken mansion under the watch of a sullen male guardian who commits her to an equally joyless sign language instructor. She spends her days in her bedroom and uses folded paper to make an intricate replica of New York, where her mother, a famous actress in silent films, lives a life from which Rose has been blocked out. Intercut with her story — which plays out in black-and-white and without spoken dialogue — is that of Ben, who we find in 1977, living with his aunt in Gun int, Minnesota, shortly after his mother’s sudden death in a car crash. Ben obsesses over the identity of his father, and fills his room with artifacts and ephemera. “You really do live in a museum,” we see his mother tell him admiringly in one of the flashbacks that fill the film’s first act.

After a freak accident in which he is struck by lightning, Ben, too, becomes deaf. To search for their lost parents, Ben and Rose both escape to New York, where their stories converge across time at the American Museum of Natural History. It’s there that Rose meets her estranged brother Walter (Cory Michael Smith) and acquires the catalogue to an exhibit of “cabinets of wonder,” which by 1977 has found its way (we only slowly learn how) into Ben’s hands. The walk-in cabinet at the center of that 1920s exhibition has, in Ben’s era, been relegated to an attic within the museum, where his new acquaintance Jamie (Jaden Michael) — the young son of a museum employee — has made it into a kind of private hideaway.

Never in Haynes’s films have any of his characters more literally tried to make a museum into a home. This effort doesn’t go disastrously wrong. Ben, Jamie, and Rose end up with more freedom than any of Haynes’s previous characters, and they use it to assemble comfortable living spaces in which everything — in the terms Haynes invoked in Mildred Pierce — “actually matters.” Nothing could be further than Jamie’s enveloping, cozy attic room from the mausoleum-like suburban houses that populated such movies as Far From Heaven and Safe.

Photo: Wilson Webb. Courtesy The Weinstein Company.

We’ve been carried far, too, from the hushed, shimmering, and recessive vision of 50s New York that Haynes and his regular cinematographer Ed Lachman evoked in Carol. The city Rose sneaks into to see a rare stage performance by her mother Lillian (played, in her fourth appearance in a Haynes picture, by Julianne Moore) is all movement and commotion. The New York in which Ben arrives, 50 years later, is a racially diverse paradise where pedestrians move down the street in slow motion to Esther Phillips’s funky “All The Way Down.” This dreamy vision of the city is as much cinematic pastiche as it is historical recreation; it riffs on the 70s New York of, say, Dog Day Afternoon much like Far From Heaven riffed on the suburbia of Douglas Sirk. But it puts fewer checks on its characters’ movements or desires than any setting Haynes has previously imagined.

And yet the children in Wonderstruck aren’t much happier than the children in Haynes’s earlier films, for all the relative freedom they enjoy. Jamie is lonely and friendless, Ben and Rose both obsessed with their missing parents. Haynes’s earlier movies drove at pathos; for all their irony and allusion, they were meant to cut their viewers to the quick. (“If it doesn’t touch you in some way,” Haynes told an interviewer about Poison in 1992, “if it ultimately doesn’t overcome its structure, its intelligence, its cleverness, I would be unhappy.”)

Wonderstruck, in contrast, doesn’t move towards a tragic denouement so much as float along in a mood of sadness and loss. The houses and buildings these characters inhabit — Jamie’s retreat; Walter’s spacious home; Ben’s cluttered bedroom in Minnesota; the used bookstore he visits (the uptown institution Westsider Books) — console them rather than subject them to pressure or threats, but they don’t quite give consolation enough. The closest communion Rose will enjoy with her mother, we gather, will be going to see her in such imagined Griffith-like movies as Daughter of the Storm, which we see the girl watch in a New Jersey movie house in one of Wonderstruck’s loveliest, saddest scenes. Ben, whose absent father we learn was a wildlife researcher, will keep having nightmares about being chased by wolves like the disorienting, feverishly cut dream sequence that opens the film. Both kids will go on seeing the world from the remove their deafness imposes on them. And the family reunion Ben does have in New York will be bittersweet, an encounter with the one relative who can tell him how much he’s lost.

Photo: Mary Cybulski. Courtesy Amazon Studios and Roadside Attractions.

III.

Wonderstruck is, in some senses, a natural next step for Haynes. With Mildred Pierce and Carol he had already migrated away from the intricate conceptual gambits, biting social ironies, and pastiche-like visual textures that defined his earlier work, from Poison and Dottie Gets Spanked to the exacting Sirk emulation of Far From Heaven and the six different Dylan tributes, starring six different actors, that collided in I’m Not There. Mildred Pierce and Carol were more somber than their predecessors. The rhythms at which they moved were smoother and less disjunctive, their color palettes not as bright.

But Haynes’s new film still does seem to mark a shift in his thinking. It’s the first film he’s made in which the business of fitting out domestic spaces like Jamie’s attic or Ben’s bedroom — designing them, dressing them, decorating them — proceeds smoothly, without devolving into an occasion for anyone to be stigmatized, excluded, or caught in a social transgression. The threat of such exposure has always been an important source of energy in Haynes’s movies: it pushed his Dylan and Bowie figures into more extreme forms of self-reinvention and drove the wives and mothers in Safe, Far From Heaven, and Carol to similar extremes of heartbreak or desperation. No comparable source of drama emerges in Wonderstruck to take its place. And so for the first time we have a Haynes film in which no one seems to desire anything terribly off-limits.

Haynes’s earlier movies proceeded from the premise that, as he said in 1991, “children are often in control of situations that they seem to be victims in, that they are full of desire — sexual desire,” which also makes them “the objects of rituals of severe humiliation.” Steven’s dark obsession in Dottie Gets Spanked with seeing the TV star he idolizes get punished and humiliated was the kind of forbidden lust Haynes often used to assign his young protagonists. These were kids shamed and isolated by their queerness, sexual precocity, or deviance from convention. (The closeted adults in Haynes’s later films — Dennis Quaid’s breadwinner in Far From Heaven and Cate Blanchett’s housewife in Carol — find themselves estranged from their own children before the movies’ ends.) Such estrangement seems not to have occurred to Ben or Rose, who never want much more than the comfortable family lives they’ve been denied. If the spaces they inhabit don’t seem to restrict the scope of their desires, it’s perhaps because they don’t have desires complicated or unwholesome enough to restrict.

Some moments in Wonderstruck do give us glimpses of the wild territory on which Haynes’s previous movies about childhood unfolded. When Ben finds his slightly older cousin smoking and wearing his late mother’s clothes, the film opens onto intriguingly unstable ground; but we leave the cousin behind as soon as Ben decamps to New York. The film’s great sequence isn’t between these two but between Ben and Jamie. They’ve just chased each other through much of the Natural History Museum in a game of dodges and teases and arrived in the secluded room Jamie has fashioned out of his cabinet of wonder. Ben hasn’t realized that Jamie knows the address of the bookstore he wants to find — the one his father used to frequent — but has withheld it to keep Ben from running off.

They communicate back and forth using a pad of paper, codify their friendship with a dance to one of Jamie’s LPs (Ben listens via the vibrations of the record player), and eventually pull back the curtains on the dusty, half-obscured cabinet itself. Haynes lets the sequence sprawl as the two boys warm to each other and relax in the space, into which the camera too seems to settle as it gets deeper into the scene. Only after some hours does Jamie admit that he knows the bookshop’s whereabouts after all. Ben is furious. “Why did you wait until now?” he asks. “Because I don’t have any friends,” Jamie answers.

This extended drama of seduction — in which one of the boys strings the other along to ease his own loneliness — suggests a complicated mixture of guilelessness, hunger, and burgeoning sexuality that the rest of the movie rarely takes up. Soon we go back on the hunt and the film resettles into a more familiar key. It has some pleasures still to come, including a stirring late appearance from Moore, the actor with whom Haynes has always seemed to have his most privileged, intimate rapport. But that long interlude between Ben and Jamie is something more alive and less predictable than anything else in Wonderstruck. As the kids move through this museum they’ve fitted out as a kind of domestic haven, we see them realize that their desires might range more widely and into more destabilizing territory than they’d thought.

Like Therese (Rooney Mara), the young woman who falls for Carol during one of her shifts in the toy section of a department store, or Cathy in Far From Heaven, who only lets herself acknowledge her love for Ray near the end of that film, they seem to have been caught at the very moment at which the structure of their feelings starts to shift. It’s as if they suddenly no longer know whether it’s just parents and friendship that they need, and they keep being pushed further into this uncertainty by the space — half-home; half-museum — through which they move. The scene they share suggests that Haynes is at his best when the rooms in his movies are redolent with unspoken desires and the people whose stories he’s telling want more than they can say.