II. New York

by Erin Sheehy

Despite the real terror behind these images, they look no more dramatic than those of our own era. The police wear short sleeves. They smoke cigarettes, lean against parked cars, idly check their rifles.

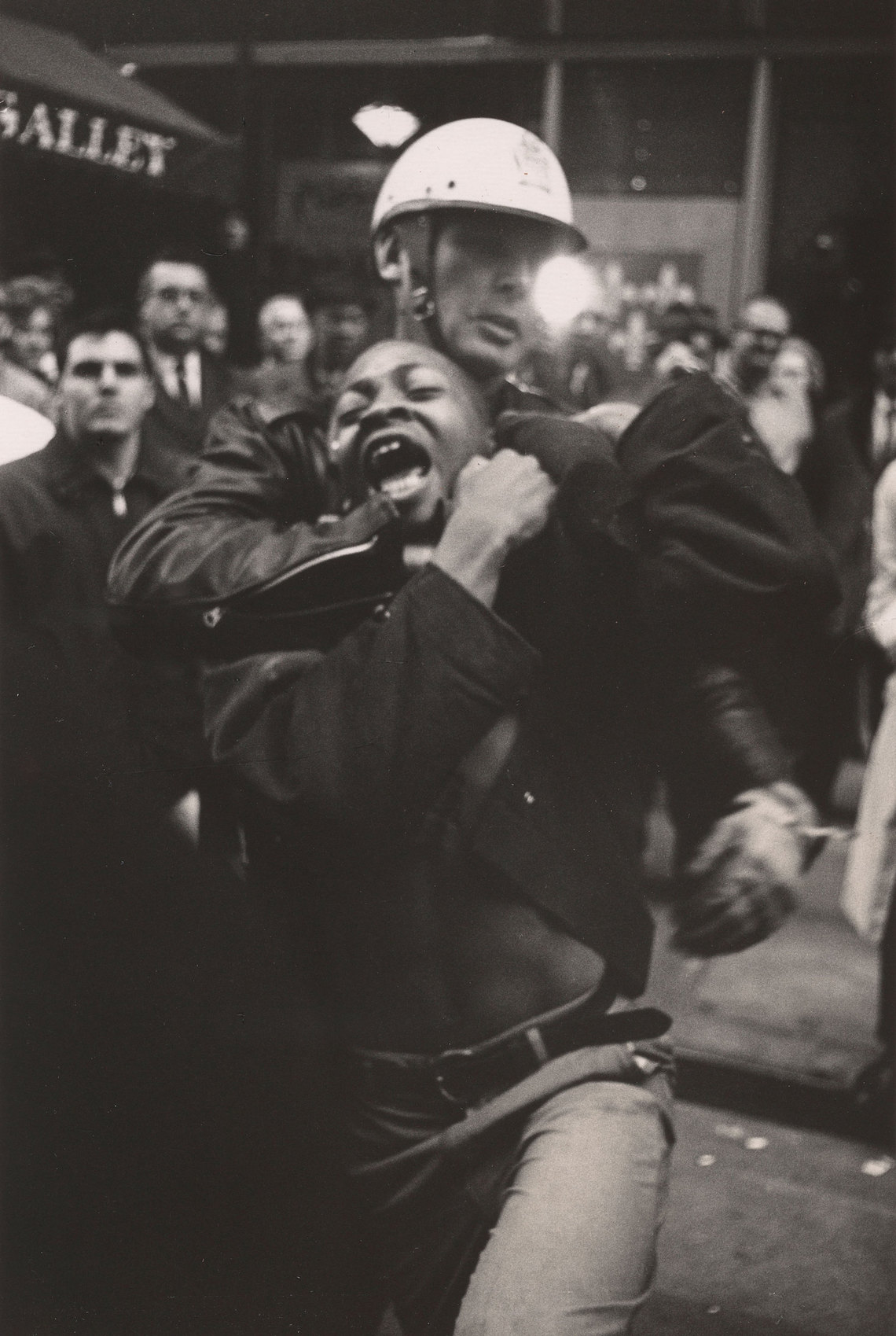

Danny Lyon. Arrest of Taylor Washington, Atlanta. 1963. Vintage gelatin silver print. 9½ × 6¼ in. © Danny Lyon. Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

Danny Lyon: Message to the Future

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

June 17 – September 25, 2016

Diane Arbus: In the Beginning

Met Breuer, New York

July 12 – November 27, 2016

Last summer the young artist Yulan Grant posted to Instagram a video montage set to the song “Mama Said,” an old girl group classic. The opening vocals ring out shrill as sirens while a camera pans across fires burning roadside. Protestors hang the pan-African flag from scaffolding; demonstrators carry signs that bear the names of women murdered by police; a cop grapples with a crowd while a large black man with a worried brow mouths the word “stop”; a policeman in a Texas subdivision draws his gun on a group of black teenagers in bathing suits, then grabs a girl in an orange bikini by the neck and shoves her face into a patch of lawn.

That same summer Ta-Nehisi Coates had published Between the World and Me, a book-length letter to his son, in which he painted the United States as a nation of inexorable racial violence. When the Shirelles sang “Mama said there’ll be days like this” decades earlier, generations of parents had been preparing their children for a world that didn’t see them the way they saw themselves. More than fifty years later, Coates’s widely acclaimed book did the same. And so by setting contemporary images to a 60s song, in a format — a montage of violence overlaid with pop music — that we’ve come to associate with documentaries about that decade, Grant didn’t just reiterate how little has changed since then. She also gave these images historical ballast, an importance on par with the civil rights movement. The video seemed to say: no matter who you are or what you believe, if you live in America today, this is the B-roll footage to your life.

These things were on my mind when I went to see “Message to the Future,” a sprawling retrospective at the Whitney of the photographs of Danny Lyon. Lyon has spent his life documenting society’s outlaws and outcasts — protestors, bike gangs, prison inmates, Native Americans, immigrants. He developed a New Journalism approach to photography: subjective, anti-authoritarian, and enmeshed in the lives of the people he chronicled. In 1962, when he was just a 20-year-old student at the University of Chicago, Lyon hitchhiked to Georgia to photograph the civil rights demonstrations there. He befriended John Lewis and was enlisted by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to be its first official photographer. For the next two years, he was on the front line at sit-ins and marches, and his photos were used for many SNCC pamphlets and posters, some of which were on display in this show. (The exhibition was organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; it opens at the de Young Museum there in November.)

Lyon’s photos from that era are at once familiar and shocking. Stokely Carmichael, alone and wide-eyed at the center of a crowd, faces the Maryland National Guard moments before they attack him with a chemical gas that will leave him unconscious until the following morning. National Guardsmen in gas masks and riot helmets pull at the leg, arm, and shirt of another SNCC photographer, while Carmichael grabs at his other leg; the photographer is suspended in midair, legs splayed, one hand still gripping the pavement. Onlookers watch the funeral procession for the four girls who were killed when the Ku Klux Klan bombed their church in Birmingham, Alabama. We see not the procession but the crowd, faces tense and furrowed. A woman touches her cheek lightly. An old man folds his arms around himself. Behind him, disembodied hands clutch a tissue.

In the summer of 1963, Lyon snuck into a cinder block stockade outside of Leesburg, Georgia, to photograph a group of girls, aged 13 to 15, who had been held there without charges for more than a month. They were fed undercooked hamburger meat and slept on the cement floor. In a photo on display at the Whitney, the girls stare at Lyon through a broken window; some of them smile. There is debris all over their cell. They had been arrested for protesting a segregated movie theater, and their parents had had no idea where they were.

Despite the real terror behind these images, they look no more dramatic than those of our own era. The police wear short sleeves. They smoke cigarettes, lean against parked cars, idly check their rifles. In a shot of police resting in a shady driveway in Clarksdale, Mississippi, one cop flips off the camera while another grabs his crotch. They don’t look menacing so much as apathetic. Of course, apathy can be deadly, and what’s the difference between a smirk and a scowl when both are followed by a swing of the billy club? But the absence of the outlandishly militarized cops we see today is a reminder that we’ve grown accustomed to being policed by people who look like they’re in war.

In 1967, Lyon applied for — and, shockingly, was granted — access to Texas’s state prisons. He shot there for 14 months. The most astounding photos from this series are from the prison work farms. Inmates in white uniforms and white sun hats hunch over, straight-legged, picking cotton; the full sacks they drag behind them are as large and long as bodies. In one photo, a man with heat exhaustion lies collapsed in the bed of a pickup truck, with ice cubes melting on his chest and down his unzipped pants. Naked black men, their clothes in heaps on the ground, line up to be inspected by white guards in cowboy hats. This looks, frankly, like slavery. The series is a stark reminder of programs in the American south, in place until the early 20th century, in which work crews of convicts were leased out to private companies; of Angola Prison, which was once a slave plantation, where prisoners still spend their days picking cotton; of the uninterrupted use of penal labor in America.

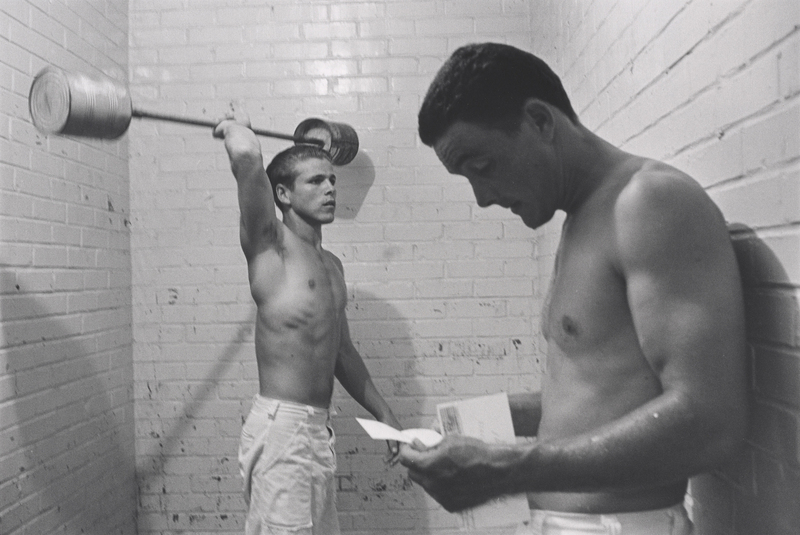

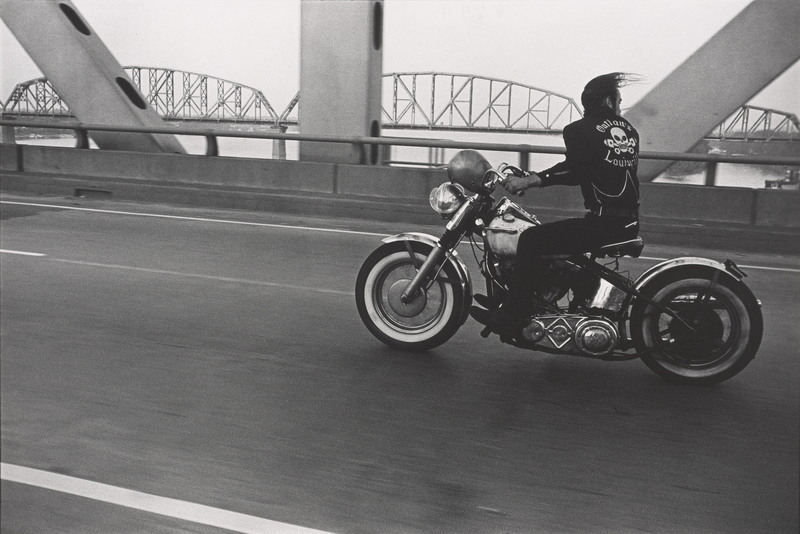

The open road, expanses of dry dirt and grass, and glaring gray sky are recurring motifs in Lyon’s photos — he saw himself as a follower of Kerouac, and highway America as a landscape of freedom. He often shot in the bright light of day. One of his most defining photographs is of the Chicago Outlaws biker gang (he was a member in the late ’60s), shot from behind as they crest a hill, their black jackets filled with wind so that they look like swollen ticks. It’s not clear what lies ahead of them, just power lines and a bright stretch of sky. There’s a visual echo — an inverse — of this shot in Lyon’s photos of the work farms and the prison yard, in which convicts appear as crisp white flecks in a dusty expanse. From the gun tower we see a row of men below, running in from the field like insects: though imprisoned, they are pictured in the wide open space that is Lyon’s emblem of possibility.

Compared to Lyon’s work, the photos in “Diane Arbus: In the Beginning,” seen this summer at the Met Breuer, feel claustrophobic. Arbus’s is a realm of isolation, closely cropped and hemmed in. Darkness creeps in from the edge of the frame, threatening to swallow her subjects. The photos in this exhibition were taken between 1956 and 1962, after Arbus decided to leave her career in commercial fashion photography. She took most of these early photos using a 35mm Leica and only available light, before switching to the medium-format Rolleiflex and flash she would become known for. These small, grainy pictures give the impression of fog, damp air, impending rain. We see rows of bleary streetlamps, long columns of misty fluorescent light in pool halls and snack bars. From TV screens to movie projection booths, from bare bulbs in hotel rooms to display lamps in shop windows, Arbus depicts a New York of perpetual obscurity dotted with beacons of light.

Not organized by theme or date — Jeff Rosenheim, the Met’s photography chief and this show’s curator, hung the show’s hundred-odd images on freestanding panels in a single gallery — the photos reflect the wanderings of a photographer finding her tone. Arbus prowled places like Times Square and Coney Island, magnets for the nocturnal, the restless, and the strange. But as she works her way to the intimate, confrontational portraits that would become her signature, we also get shots of passersby on the street, the insides of movie theaters, storefront windows, a stray newspaper caught in a breeze.

10 × 6½ in. © The estate of Diane Arbus, LLC. All rights reserved.

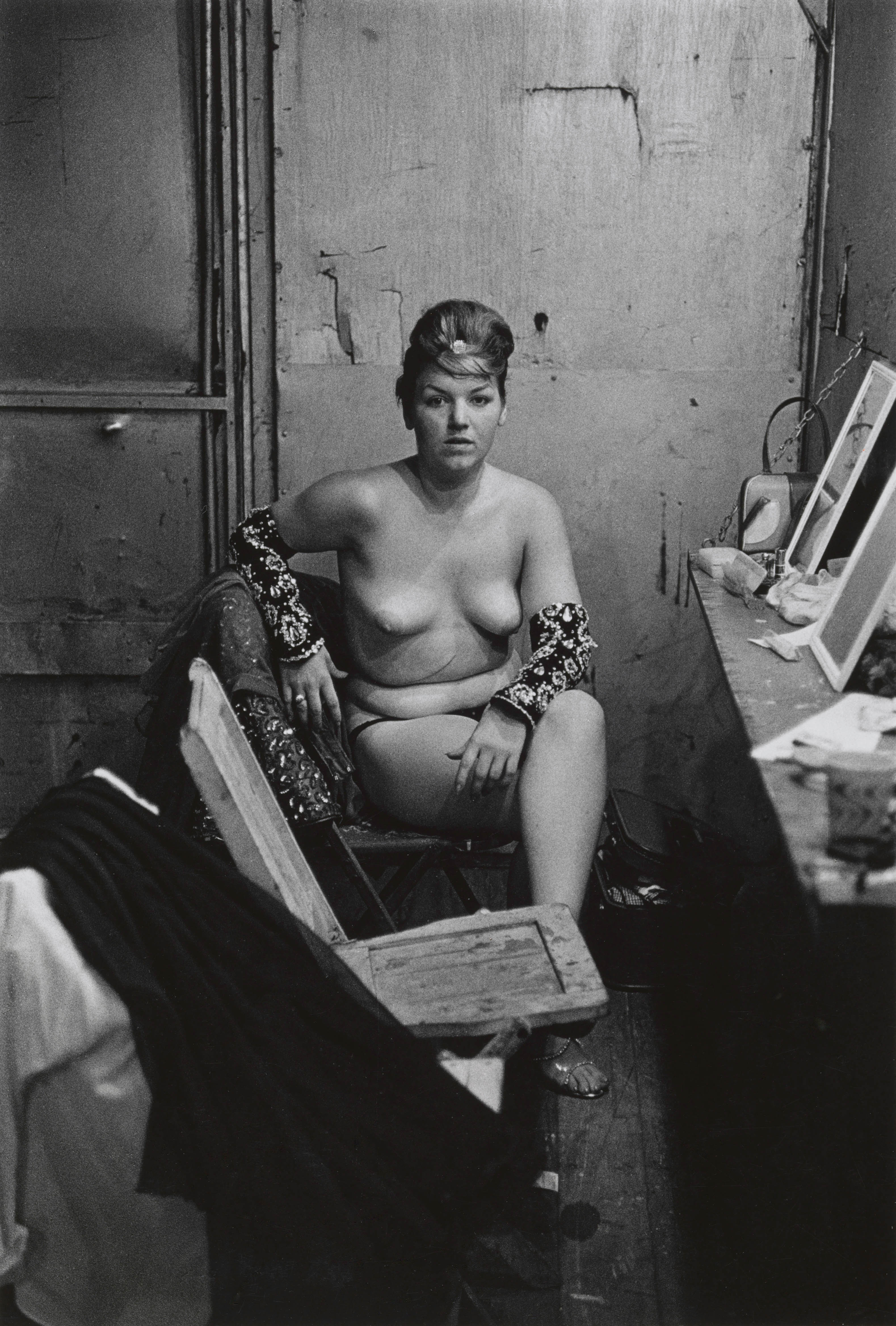

She would later famously document giants and dwarves in their kitchens, beds, and parents’ homes, but here she shoots sideshow performers from the audience, a few rows back. Her subjects are surrounded by the blurred heads of onlookers. A female contortionist is curled into a ball in front of a crowd of men at a dime museum; a child in a straw boater holds his lapels out like suspenders, his mouth in an exaggerated O, performing impressions for a room full of dreary, broad-shouldered men. A pair of cha-cha girls in sequined leotards dances for two bemused ladies and a stern-faced gentleman who grips his knees, a gesture, perhaps, of suppressed pleasure. While some of this seems purely practical — she had not yet gotten close to her subjects — it also puts spectatorship at the forefront: freaks on display for the judging classes.

Arbus sometimes photographed her subjects from just outside a doorway, like the woman she captures reclining on her narrow bed in a cluttered hotel room, or an old lady in a swim cap showering at a Coney Island public bathroom. Others she shot through windowpanes; sometimes you can see her reflection in them. Where Arbus was often looking in on her subjects, Lyon tends to look out at his, especially in his biker series, where he shoots them from behind a fence, through an upstairs window, or while trailing them in a car, while they race, ride, or stand around admiring bikes. There is motion in his photos. His subjects are often out in the world doing things. Lyon deals with groups, marginalized by society but not isolated. Arbus’s photos are still and solitary, her subjects pinned like butterflies.

The young Arbus and Lyon were experience junkies. Both middle-class Jews from New York, they used their cameras to strain against the boundaries of safety and propriety, stalking the margins of society for a sense of adventure, danger, and excitement. “I grew up feeling immune and exempt from circumstance,” Arbus once said. “One of the things I suffered from was that I never felt adversity. I was confirmed in a sense of unreality.” Their adventures took classically gendered forms: Lyon out on the road, his lens trained on “big issues,” each project taking him further afield; Arbus boring deeper and deeper into interior worlds, going home with her subjects, getting them to disrobe, to reveal themselves more fully.

They were both deeply entangled in their subjects’ lives: while working for the SNCC, Lyon spent so much time with executive secretary James Forman that Forman liked to joke he had a white chauffeur. (Lyon played along, driving him to events and opening his door for him.) Arbus stripped with the nudists she photographed and had orgies with her subjects. The giant she famously photographed at home with his parents said she “came on” to him.

Lyon’s work has often been awarded a sort of moral certainty, while Arbus’s work has always been complicated by moral ambiguity. “I am not ghoulish, am I?” she wrote to a friend after photographing a woman sprawled out on the ground, waiting for an ambulance. She sometimes pretended to be a fumbling amateur so that her subjects would be more at ease; other times she wore people down with marathon photo sessions so that she could get a moment of turmoil or distress. She didn’t like the people she photographed to see her finished portraits.

The photos at the Met Breuer are less filled with circus freaks and more with society ladies, “normal” people, which makes apparent Arbus’s interest in revealing the grotesque in each of us. Burly matrons wear pearls and queen-for-a-day furs so grimly they look like they’re government-issued. Through Arbus’s lens, a little girl is rendered so savvy and world-weary that her pom-pom headband seems ridiculous. Clothes never sit quite right. There is a cruelty in Arbus’s reveal, though the soft focus of these Leica shots is kinder and gentler than those of the later Rolleiflex, which made visible the stubble of a female impersonator’s shaved eyebrows or a dwarf’s profuse nipple hair.

The photos that seem like the greatest collaboration between photographer and subject are Arbus’s shots of female impersonators, who are already radical in their self-definition, hyper-attuned to the landscape of others’ perception of them. Often set in dressing rooms, with costumes behind them, looking in mirrors, in various states of undress, their photos feel more like a striptease than a pulling back of the curtain.

Wayne Koestenbaum once asked whether Arbus humiliates her subjects or her viewers. Are we uncomfortable with her imagination, or our own? Arbus played in the gap between how we present ourselves to the world and the way we are perceived. For many, this gap is shameful and uncomfortable to think about.

But when I look at Arbus’s photos alongside Lyon’s I remember that for some, this perceptual gap can actually be deadly. Though Arbus’s work doesn’t engage directly with politics, her imaginative landscape has implications for the world we live in today. When he testified before a grand jury in September 2014, the Ferguson, Missouri police officer Darren Wilson referred to Michael Brown, the black teenager he shot to death, as a “demon” with “Hulk Hogan” strength. “It looked like he was almost bulking up to run through the shots,” he explained about shooting at Brown a dozen times, “like it was making him mad that I’m shooting at him.” (Wilson was not indicted.) During the Rodney King beating trial, an officer called King a “monster-like figure akin to a Tasmanian devil.” He too was suggested to have “Hulk-like strength.” These descriptions are reinforcements of the longstanding stereotypes of black brutes and superpredators that have lived in the American imagination for centuries. Society contorts ordinary people into freaks and monsters all the time, with deadly results.

Extreme fear or stress can give a person tunnel vision — it’s a widely recognized issue among police officers involved in shootings. When a person experiences tunnel vision, the periphery fades, the edges blur, and he is only able to focus on the object of his fear. His vision becomes close-cropped, hemmed in. Darkness creeps in from the edge of the frame. If Lyon’s photos show how little has changed in the structures that constrict our lives, Arbus’s are perhaps more terrifying, showing that the imagination may be just as intractable.