Kissed by Magic

by Ben Eastham

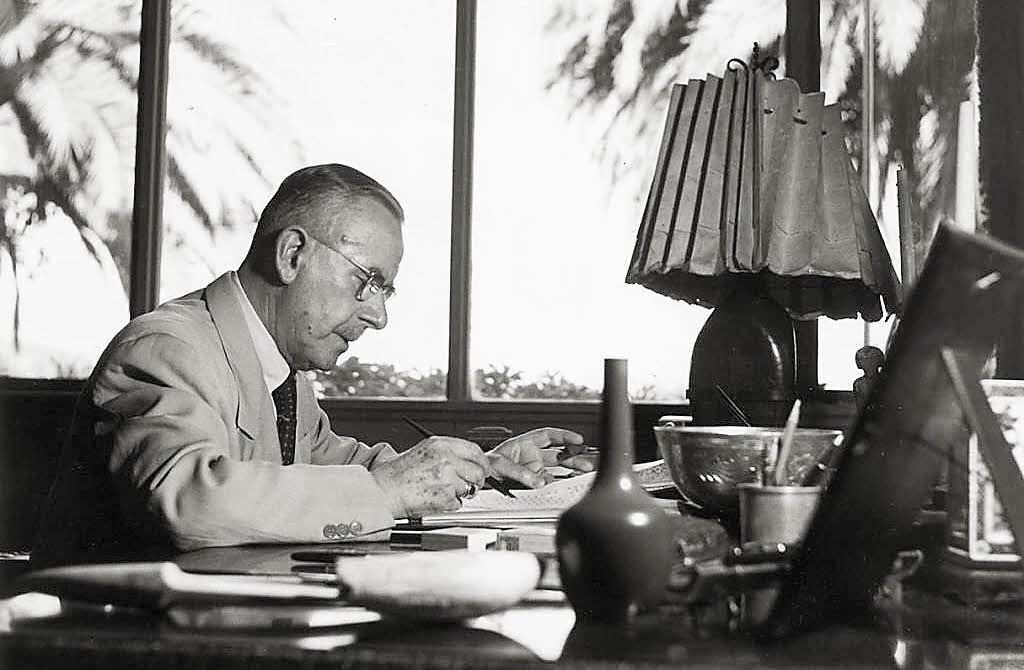

The Thomas Mann House in Pacific Palisades, after a recent renovation.

This article appears in Even no. 5, published in fall 2016.

I am finally disabused of the idea that the spirit of an artist leaves an indelible stamp upon the place of his work when, in Los Angeles this summer, a realtor encourages me to renovate the rooftop terrace overlooking the swimming pool beside which Thomas Mann wrote Doctor Faustus. It would make, he suggests, a spectacular outdoor gym. We strain to catch a glimpse of the ocean through the eucalyptus trees that border the property, which squats low upon a leafy plot on San Remo Drive. We have moved through a series of empty rooms, which show little sign of refurbishment in the 74 years since the installation of the Mann family. The lounge is a wide, high-ceilinged space leading through a set of French windows to a tiled patio; at the rear of the ground floor is a library lined with bookshelves, which does at least go some way to evoking the writer’s ghost. From our elevated vantage I gaze back at the pool, gleaming under the Pacific Palisades sun, and I am visited by a vision of Theodor Adorno batting a beach ball across the pool to Mann as they lament the corruption of the German soul. Schoenberg sulks beneath a sunshade.

I made an appointment to see this house, a Bauhaus-ish two-story curio built for the Nobel Prize-winning exile in 1942, knowing more about German literature (examples of which I can afford) than about LA property (which I emphatically cannot). The realtor, via a series of polite inquiries about my country club memberships and preferred ski destinations, may have figured that out. Perhaps out of suspicion towards my intentions, perhaps so as not to discourage tearing down this relatively modest building on an obscenely valuable plot of land, the realtor has not mentioned that the house we’re viewing — designed by the architect J.R. Davidson, another German emigrant, and now on the market for $15 million — is is a historic record of that strange period when Germany’s interwar avant-garde played out a sun-kissed exile in California. Discretion can be discounted as an explanation for the omission: he let slip before we walked through the door (after the disclaimer that he didn’t like to drop names) that Goldie Hawn and Tom Hanks would be my neighbors.

Back in the 1940s, Mann’s neighbors included Lion Feuchtwanger, the author of Jud Süß, while the novelist Alfred Döblin, the composer Hanns Eisler, and the philosopher Max Horkheimer were elsewhere in the city. Schoenberg consolidated his radical break from the history of European music in nearby Brentwood, now home to John Travolta. Down in seaside Santa Monica, just a few minutes’ walk from what is now Muscle Beach, Bertolt Brecht lived in a charming clapboard beach house and composed his Hollywood Elegies:

…In these parts

They have come to the conclusion that God

Requiring a heaven and a hell, didn’t need to

Plan two establishments but

Just the one: heaven. It

Serves the unprosperous, unsuccessful

As hell.

Like those Europeans who refuse to tip bar staff as some kind of obscure protest against American attitudes to the provision of labor, Brecht doesn’t seem to have entered into the spirit of the place.

These Germans’ and Austrians’ collective exile stands as a curious anomaly in the history of transatlantic intellectual exchange. Their legacy on American culture is apparent in film noir (Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder were exiles who remained on the west coast), experimental music, and the adoption of the Frankfurt School as a keystone of critical theory, though the New World doesn’t, in the case of Mann or Brecht, seem to have had any noticeable effect on their own work. (Contrast that with exiles on the other coast: Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie is a jubilant paean to New York markedly different from his European compositions.) Visiting for the first time, it’s tempting to speculate that the displacement of Mitteleuropa to California had other consequences: in the development of west coast surf culture (the celebrated Malibu surfer Miki Dora, for instance, was born in Budapest in 1934), or in hippiedom and the Californian cult of physique, both of which might appear as rather more benign offshoots of the mystical, communitarian strain of body-obsessed Nazism.

Ironic that these victims of fascism were in turn forced out of the land of the free by a homegrown brand of ideological hysteria. In 1947, Brecht testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee and went back to Europe the next day; disgusted by the rise of McCarthyism, Mann left too. He and his Nobel went to Switzerland in 1952; the hideaway in Pacific Palisades passed into American hands, and now its frayed wall-to-wall carpets and his-and-hers sinks just barely hint at the tastes of the initial occupant. My own departure from Mann’s house is only slightly less fraught. Shaking the realtor’s hand by the gate, I realize that I have only the time it takes him to return to lock up the doors to conceal the fact that I have neither a driver nor a luxury car at hand. Carlessness in Los Angeles is tantamount to a crime, and absolutely irreconcilable with the illusion of wealth I have been laboring to project. (Laboring without much success: novice Brit that I am, I thought Sunday real estate viewings required a blazer.) Once his back is turned I break into a frantic, heaving run across the asphalt, and hide behind the street’s only available cover, Goldie Hawn’s bush. I pray to the god of gutter journalism that no local resident is calling the armed private security company prominently advertised on every lawn. My Uber is seven minutes away, on Sunset Boulevard.