Bad Education

by M. Neelika Jayawardane

Rhodes falls. University of Cape Town. 2015. Photo: Desmond Bowles.

This article appears in Even no. 5, published in fall 2016.

I.

Before he became prime minister of South Africa in 1958, Hendrik Verwoerd headed up the ministry of native affairs, where he was in charge of “native” education. His ministerial portfolio included drafting the Bantu Education Act, to “train and fit” black South Africans to play their designated role in apartheid society, that of “hewers of wood and drawers of water.” In 1953, he bluntly elucidated the National Party’s markedly different education policies for black and white South Africans: “There is no place for [the Bantu] in the European community above the level of certain forms of labor.… What is the use of teaching the Bantu child mathematics when it cannot use it in practice? That is quite absurd. Education must train people in accordance with their opportunities in life, according to the sphere in which they live.”

Verwoerd was also responsible for the displacement of tens of thousands of black South Africans to largely unarable parts of the country, which were designated as “homelands” for black people. Where black labor was indispensible, such as in the Johannesburg mines, and in the households of whites, black South Africans were forcibly moved to designated areas outside the perimeters of white cities. On June 16, 1976, in the South Western Townships of Johannesburg, more than 10,000 students began a peaceful protest of a new language policy mandating that the language of instruction in all schools would be Afrikaans. Though their mother tongues were a variety of South Africa’s many “local” languages, the students’ choice was to be taught in English, which was the language that state-aided mission schools had instituted, and was the language in which Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, Winnie Mandela and those of earlier generations of black South Africans had been educated. The decision to make Afrikaans the compulsory medium of instruction for crucial subjects, including mathematics and social studies, would inevitably disenfranchise a generation: teachers were to begin instruction of those subjects in Afrikaans, although they had little to no knowledge of the language. The outcome of the 1976 Soweto Uprising is well known: an estimated 176 students were killed by police in Soweto alone, and over 700 students were shot dead around the country. Widespread repression followed, as well as international condemnation of the apartheid state.

Kemang Wa Lehulere’s exhibition “The knife eats at home,” which took place at the Stevenson gallery in Johannesburg this southern winter, explored the ways in which South Africa’s education system continues to exert a legacy of violence, long after the end of apartheid. His work, which often involves skilled carpentry, almost winks at Verwoerd’s curriculum for black students, where “practical subjects,” including wood and metalwork, were meant to train them to remain in servitude to whites. Yet beyond the inherent humor is a thread of pain. His sculpture, paintings, and drawings demonstrate that though violence in democratic South Africa may not be as visible as it was when gun-wielding, sjambok-toting racist policemen enforced Verwoerd’s policies, today’s education system — barely decolonized from yesteryear — exerts everyday, quiet exclusions that culminate in an all too familiar picture. And the tactics used by educational institutions to suppress dissent — the public order police and private security firms, the teargas and rubber bullets — remind those who lived through the 70s and 80s that there are too many historical motifs mirrored in the now.

Carefully articulated syllables of an elocution lesson, and a large wooden dollhouse-like structure suspended from the ceiling, greet visitors as they walk through Stevenson’s secured glass doors. We hear a recording: a female instructor is speaking words slowly, in an American accent. The cassettes that play the American English elocution lessons (which Wa Lehulere found in Bangkok in 2014) sit in front of the suspended wooden “house.” A taxidermied African grey parrot sits in the house, facing a music stand. Upon closer inspection we see that the house is built from slats of dismantled school desks, and casual scrawls of students — accumulated over many years — brand the wood. African greys are renowned for their ability to mimic sounds, including human languages, and here, Wa Lehulere introduces audiences to the processes by which we become culturally colonized, and by which we continue the colonizing processes. We parrot what we believe is correct, sounding out words that mimic those we want to emulate. By repurposing school desks on which students attempted to leave behind a reminder of their individuality, Wa Lehulere reveals that the hours spent at these desks may have simply disciplined them into forms a still colonized world would accept. However, there are opportunities for subversion; the artist acquired a live African grey and kept it in the studio, but it never learned to parrot any words. As he laughingly told me, the parrot “resisted.”

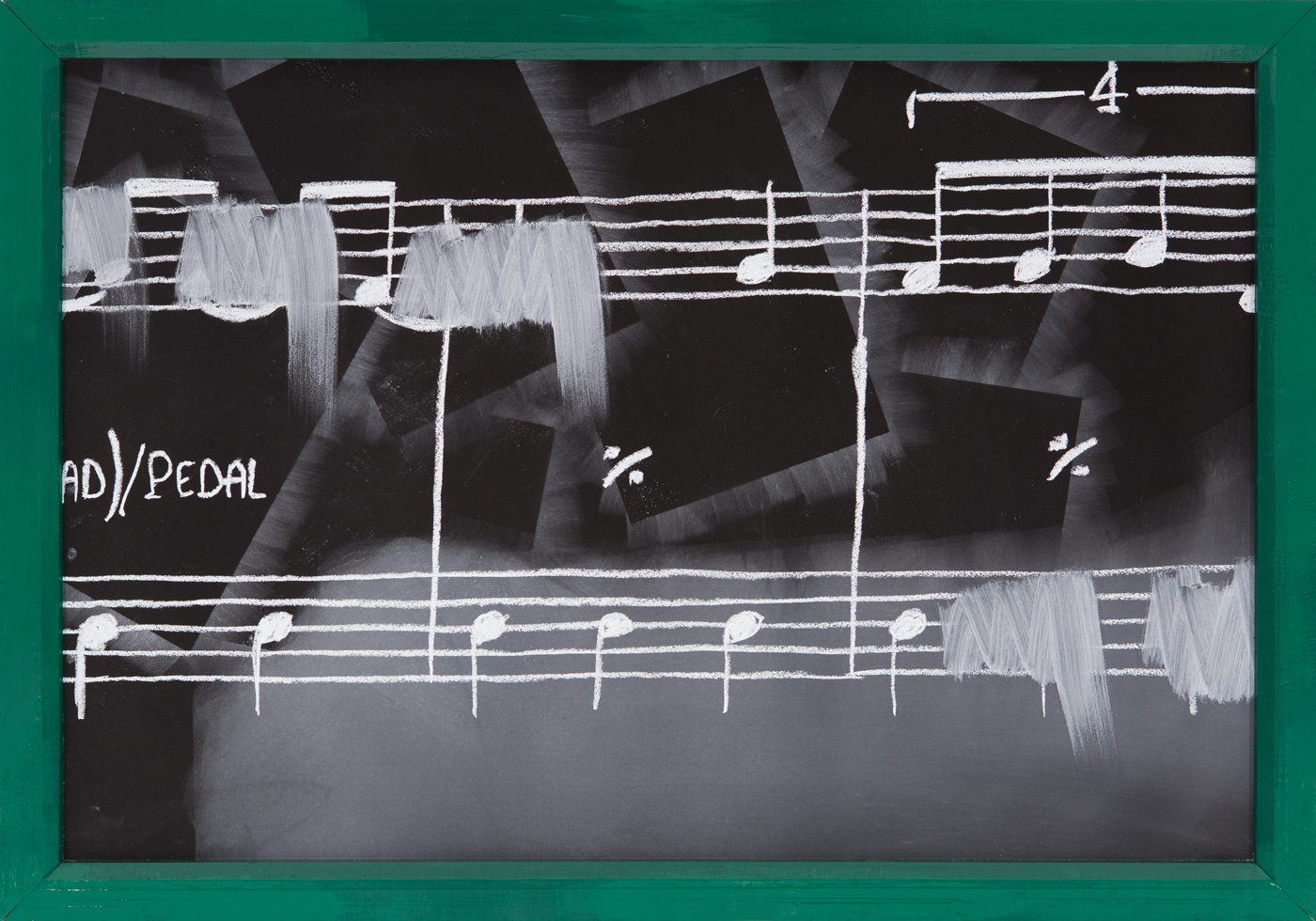

In the inner rooms of the gallery, Wa Lehulere has arranged eight beautiful ceramic Alsatians, a recurring motif in his art, on wooden stands again made from dismantled school desks. Surrounding them is a wall of blackboards with chalk diagrams and partially erased material. Elsewhere another grouping of Alsatians sit around a collection of tires, each of which has two crutches (again, fashioned out of school desks) inserted into them. They could be playthings — it’s a common game for children to use sticks to push tires down roads. But these tires have an alternate meaning: those of us who lived through the 1980s remember the men trapped in petrol-doused tires and set alight, a cruel punishment called “necklacing” for those suspected of being apartheid spies. We also recall conflagrations of tires doused with petrol, used as roadblocks against police. As Wa Lehulere notes, “In Gugulethu, where I come from, there was just one entrance and exit. They” — he means people with burning tire blockades — “would shut down a township or neighborhood when the police were coming.” On the wall next to this display of innocence and latent rage are large boards containing something recognizable: Broken Light (Feya Faku) 3 features a jazz score with certain notes erased, leaving chalk traces where the notes used to be.

The artist's obsession with school desks, he says, comes from “many hours” spent in detention for being “one of the most ungovernable students.” In South Africa, the word ungovernable has a particular connotation. In the 1980s, opposition to the apartheid government took on new urgency, and the African National Congress began to channel energy towards garnering support from thousands of youth in the townships. Radio Freedom was a favorite channel; from there, Thabo Mbeki called on youth to “make the townships ungovernable.” Wa Lehulere is from a younger generation, but the phrase penetrated his vocabulary. One of the punishments for his own singular “ungovernability” was “to erase the marks that students left” on the wooden surfaces. Now, erasure has become one of the artist’s principal techniques — especially in his drawings on chalkboards, whose collections of dogs, musical stands, and crosshatched abstractions only become more inscrutable when partially effaced.

Wa Lehulere’s downbeat, sometimes perplexing art has recently gained an international following. This October his first American museum exhibition, "In All My Wildest Dreams," opens at the Art Institute of Chicago, and he is this year’s recipient of the Deutsche Bank prize. (He also produced a portfolio for the inaugural issue of this magazine.) But that commitment to a certain opacity, so essential to Wa Lehulere’s practice, has a resonance in postcolonial contexts that may not be evident to those who only see his art, or the art of many other South African artists, in Chicago or Berlin. The state, and those powerful few who benefit from the privileges handed out by the state, expect the native, the other, the colonized to subject themselves to X-ray-like revelation machinery, exposing the most sacred parts of their private and collective selves. The refusal to reveal, the decision not play the friendly, appeasing native, is a refusal to submit to the colonial and apartheid methodologies of information collection and control. “The knife eats at home,” the show’s title, is a Sotho parable, but the artist made no effort to relate that fable or to clarify its meaning. Only those who speak Sesotho well enough, and are familiar enough with Sotho culture to know its stories, will fully understand.

II.

As recently as the 1980s, the apartheid government allocated nearly ten times the funds per capita for a white child in public education as it did for a black child. Although there have been significant efforts to transform primary, secondary, and tertiary education since the ANC came to power in 1994, there have been few real changes in the structures, institutions, policies, and practices of South African education. One recent study estimated that 65% of school leavers are functionally illiterate. A full 80% of those who meet university entrance requirements come from only 20% of secondary schools, most of which were previously reserved for white students.

In 2015, almost 40 years after the Soweto student uprising, South Africa saw nationwide student protests that decried systematic exclusion and racism, curricula that did not reflect the fact that the universities were located in an African country, and proposed fee rises that would make it impossible for a majority of black students to continue their education. They had enough political education, and had read enough Frantz Fanon, to identify structural racism and to identify the ways in which the current ANC government simply reproduced apartheid violence. Many also noted instances of unquestioned, everyday racism by white students, staff, and faculty that left them deeply unsettled. If a black student or faculty member called out a white student or faculty member, they would say in defense that they “did not see race.” How does one begin to “respond to that level of crazy?” one black student at the University of Cape Town asked me.

To enter such benignly hostile spaces, every day, required an emotional and psychological labor that left a group of students unable to face their studies. Together, black students at UCT — many from middle-class families that could very well absorb the fee increases — embraced what the activist and academic Steven Salaita calls “the beauty of disrepute.” They put aside expectations of a degree, job, income, and house in the leafy suburbs (in formerly whites-only areas) in order to bring attention to power imbalances and gross inequalities that those in power would rather not address. Protests had already begun in January 2015, at university campuses across Kwazulu-Natal and at Tshwane University of Technology, both of which have larger than average percentages of students from poorer backgrounds, when hundreds of students were unable to register for classes because of outstanding tuition fees they could not pay. Students were ordered to leave campus as the protests became violent; clashes with police and campus security guards left several students hospitalized.

Yet there was an unlikely accelerant of the nationwide student protests that rocked South Africa in 2015 and 2016: the public art and monuments erected on these educational institutions’ grounds and in their buildings. Massive statues of Cecil Rhodes, the industrialist and all-around colonial bastard, as well as such apartheid leaders as Verwoerd and D.F. Malan, remain omnipresent in South Africa and are especially prominent on campuses, visually representing what a “university” is meant to be. Cumulatively, these visual remainders of apartheid remind black students that these institutions were built to exclude them; they were not, until very recently, meant to partake in the exploration, instruction, and self-fashioning that higher education promises. These everyday visual reminders — along with policies, practices, curricula, and syllabi that continue to instruct South Africans of the glory of Europe and the successes of conquest, and the administration’s amiable and PR-honed methodologies of resistance towards change — speak to black students of their continued otherness, despite the fact that blacks form 80% of the population. Together, they control, reduce, and confine their dreams of transcending apartheid’s violent exclusions.

It was a singular act by one student that focused the country’s attention on the monumental Rhodes statue on the campus of UCT. Chumani Maxwele, who had a scholarship to study political science, commuted to the university from Khayelitsha, one of Cape Town’s poorest townships. The trip takes 20 minutes by car, but up to an hour and a half on public transport; there is no direct route to the university, so students must first travel to the city center and then backtrack to campus on a different bus. (Transport, too, retains the shape of apartheid.) The student was used to seeing Khayelitsha residents forced to collect their bodily waste in a bucket, and leave it on the roadside for waste disposal pickup. Maxwele notes, in many interviews, that his decision to pick up one of those buckets of shit, transport it to UCT’s Upper Campus, and douse the Rhodes statue on March 9, 2015, was not an instinctual act but a calculated decision, made after speaking with professors. But the sense of being alien on UCT’s campus, and the sense that the alienation had a well-designed architecture: those were not new. He shouted, “Where are our heroes and ancestors?” as a crowd gathered, before he flung the shit on Rhodes.

The resulting movement, calling for the removal of the statue, quickly amalgamated around the hashtag #RhodesMustFall. This particular Rhodes statue — designed by Marion Walgate and erected in 1934 — was prominently located at the bottom of the steps leading up to the picturesque Georgian buildings of the UCT Upper Campus, itself built on a portion of Devil’s Peak estates formerly appropriated, owned, and then donated by Rhodes. In Walgate’s depiction, Rhodes is seated in the style of Rodin’s Thinker. But where Rodin’s philosopher gazes downward, Rhodes is looking slightly up, gazing presumably towards Cairo, the city to which he infamously hoped his empire would stretch. Ironically, however, Rhodes’s immediate view was of the windswept marshes of the Cape Flats, where tens of thousands of non-white South Africans were forcibly moved during apartheid.

By April 2015, UCT’s council, under enormous public scrutiny and international attention, voted unanimously to remove the Rhodes statue from its plinth. On the day that Rhodes was displaced, the performance artist Sethembile Msezane stood on the site with feathers on her arms. She was an embodiment of the Great Zimbabwe bird: a soapstone statue taken from the ancient city, later owned by Rhodes, and still in the collection of Groote Schuur, his former estate. At 2:15 p.m. on April 9, 2015, Msezane balanced herself on her own makeshift plinth, steps above the statue, and raised her winged arms. The sky was pale blue, flecked with clouds that signal, to coastal fishermen, that a change in weather is coming. She faced Devil’s Peak, so she could not see Rhodes, but she looked at “people’s phones and sunglasses, trying to see the reflection of the statue coming down.” When she saw the shadow move, she lifted her wings and performed the Great Zimbabwe bird for four hours, until the statue had fallen.

A lecturer told me this July that he tailed the vehicle that carted the statue away; there were no real plans for where to keep it once it was removed, he explained, so it was unceremoniously dumped in a UCT parking garage. According to the lecturer, it remains there still.

III.

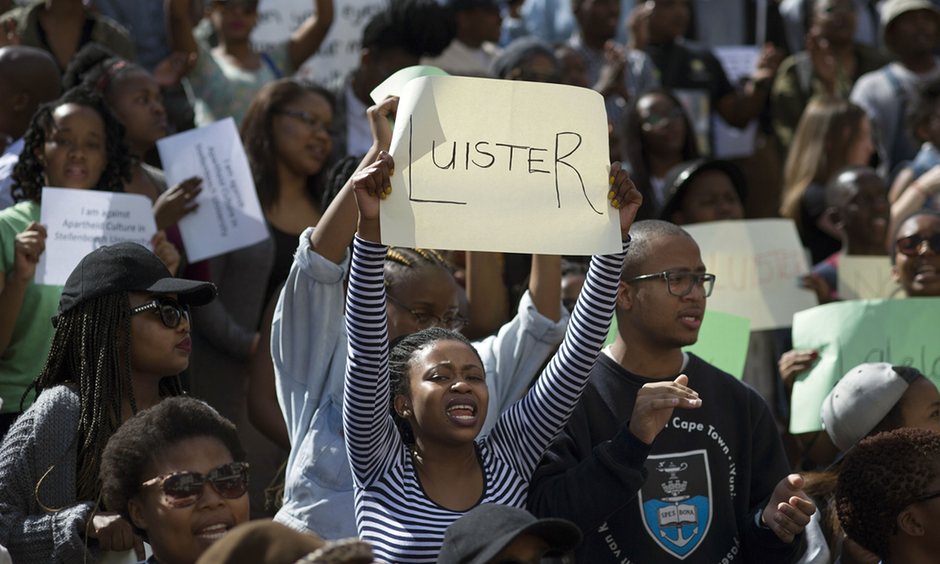

The day the statue of Rhodes as Thinker — much maligned, much shat upon by birds, clambered upon and defiled by drunken students — was dismantled from its plinth was a monumental episode in the history of South Africa, if not the entire former Commonwealth. But was it all just symbolism and iconoclasm? Following the initial success of the #RhodesMustFall movement, students across the country organized again to protest proposed tuition increases. At Stellenbosch University, a predominantly Afrikaans-language institution that continues to resist transformation, the Open Stellenbosch student movement was galvanized by the release of a film, made by a white student, Dan Corder. Luister (Listen), a 35-minute documentary released in August, documented black students’ responses to structural and everyday racism on campus, as well as the use of Afrikaans as a tool to exclude black students. By October, students in Johannesburg and Pretoria took to the streets en masse to protest proposed tuition hikes of between 10% and 12% — high enough to eliminate poor black students who were the first in their families to attend university. Demonstrations spread to at least ten other institutions; each began as a peaceful protest but ended in violence, with police firing rubber bullets and throwing smoke bombs.

Students in Cape Town, too, joined the tuition protests, which, like their iconoclastic predecessor, had an associated hashtag: #FeesMustFall. But the university also remained preoccupied by questions about art, and whether the statues and paintings that dot the university campus reinforced the inequalities that had brought protests to a head. By September 2015, UCT Council had set up an Artworks Task Team to determine which statues, photographs, and plaques were offensive or controversial. (It consisted solely of white faculty, and mostly white men.) A master’s program in curation began an “experiment,” titled Does This Offend You?, which aimed to offer “a platform for people to express their opinions regarding some of UCT’s recent decisions about public artworks on campus, while also contextualizing opinions expressed in the media.”

Earlier this year, students erected a shack on a landing immediately above the former site of the Rhodes statue. This shack, mirroring the makeshift housing of black citizens in the Cape Flats, was meant to protest a dearth of on-campus residences for poorer black students at UCT, leaving some without access to accommodation or food. When administrators announced that “Shackville” would be forcibly dismantled, students dispersed into one of the university residences and served themselves dinner at the cafeteria — this, after reportedly not having had access to food all day. One student reportedly looked up at the walls and realized that portrait after portrait depicted white patriarchs. They began hauling artworks out, making a pyre, and setting them alight, in an attempt to “decolonize” the university’s visual culture. In the mayhem, at least one artwork created by a black struggle-era artist was burnt: Keresemose Richard Baholo’s painting Extinguished Torch of Academic Freedom. The office of the university’s vice-chancellor, Max Price, was also petrol-bombed.

Unlike the fall of the Rhodes statue, which elicited a range of sympathetic and oppositional responses, the burning of artworks was almost universally decried by prominent faculty and artists, most of whom were white. Soon after, UCT dismantled Shackville and carted away 75 “vulnerable” artworks, which were placed in storage. Among the works removed are pieces by William Kentridge, Zwelethu Mthethwa, and Willie Bester, as well as a painting by Breyten Breytenbach, better known as a poet. Artworks on loan from wealthy patrons were also withdrawn. Just how UCT’s art committee decided on “vulnerability” remains murky. The removals are provisional for now; Price told one local paper, “It is our belief that the artworks will all ultimately be on display once curatorial policies have been developed.”

Like many things here, opinions on whether certain artworks’ legitimacy on a public university campus should be questioned, and why students might be driven to destructive acts, were divided by both class and race. An older generation saw the combination of student iconoclasm and subsequent administrative attempts to do damage control as censorship. (First among them was Breytenbach, who spent seven years in prison during apartheid, and who went as far as accusing the university of acting like Boko Haram and ISIS.) The inability to be in charge of symbols’ meaning exaggerated fears, among one section of the intelligentsia at least, that the nation may “go the way of Africa”: that is, lose its hard-won democratic and constitutional ideals. Yet for the students protesting the visual culture of their campuses, South Africa had not yet become a democracy robust enough to protect their right to basic human dignity in public centers of higher education.

To the shocked and scandalized responses by her fellow academics and artists, Sharlene Khan had the following response: “We must be as wary of those who destroy culture as of those who make it and promote it. In a choice between an object of humanity and humanity itself, may our choices always be each other. May you never accept any discourse that says history and products are more important than you are.” As Khan understood, art serves various social, cultural, economic and power networks at various times. You can be sickened by the destruction of art and still have the courage to ask: how did things get so bad that students of an elite university would go so far?

IV.

After a time of iconoclasm, this southern winter has been suited to painful reflection. Wa Lehulere’s work is ostensibly about unquestioned obedience, about the learned inability to speak or act against a system that is not intended to give one intellectual freedom. It speaks to the ways in which the classroom lessons that provide us with the tools to excel also confine and control us. We endure this training much like Wa Lehulere’s well-disciplined Alsatians, and accept the pressure to limit our ambitions — so much so that the education we receive only highlights our resulting disabilities.

But his art is also steeped in the value of resistance. It is about the importance of fashioning a space for yourself to think and create, to reach back into the hidden archives of memory — as he does with his aunt and fellow artist, Sophia Lehulere — even when the state has attempted to violate, silence and destabilize another generation.

One of the most powerful and prolific collectives to emerge from the generation after Wa Lehulere’s is iQhiya, which consists of 11 women aged between 22 and 32: Thuli Gamedze, Lungiswa Gqunta, Bonolo Kavula, Bronwyn Katz, Mathlogonolo Kelapile, Pinky Mayeng, Thandiwe Msebenzi, Sethembile Msezane, Sisipho Ngodwana, Asemahle Ntlonti and Buhlebezwe Siwani. The women met while studying at UCT’s art school, and they had an agenda: to counter the under-representation of black female artists, as well as the erasure of the black female body in art — whether on campus or in South Africa as a whole. A further motivation was the lack of respect they met from male student leaders in the #FeesMustFall and coterminous groups, as well as from the larger art world.

Members of iQhiya have enjoyed individual success, but some of their most powerful work has been as a collective. In The Portrait, first performed this February, each member was dressed immaculately in white. On cue, they stood on glass Coke bottles in bright red crates, balancing their body weight in an accusatory metaphor for the ways in which we fetishize black women’s pain, speaking in awe about how they are able to withstand so much. At one point, the artists also stuffed the bottles with headwraps — iqhiya, in Xhosa — transforming something decorative, or even something indicating subservience to men, into the wick of a Molotov cocktail. These students, artists, and activists, galvanized by the hashtag movements of 2015, are not the happy-go-lucky “Born Frees” that older South Africans both envied for their perceived privileges and derided for their lack of political conviction. But they are proving to be more politically astute than they were given credit for, and, at times, more ungovernable than their elders would like.