Out of Practice

Ten Issues of Even, 2015–18

In fall 2018 Even published Out of Practice, our 300-page anthology of our first ten issues. With writing from Seoul to Cape Town, Istanbul to Rio, this first book from Even collects more than 30 of the best essays on the cultural themes that define our time.

Out of Practice is now available for purchase worldwide. Here is the introduction to the new anthology, written by our editor Jason Farago.

Even, Stripped Bare

Jason Farago

The diagnosis was the easy part; the harder part was the cure. In 2014, when Rebecca Ann Siegel and I convinced each other (and, with more difficulty, convinced ourselves) that we should found a print magazine of contemporary art and culture, we knew the odds were long. The decade’s great fragmentation of attention was well underway, and it had already grown severe enough that the writing we admired had been rechristened with a cutesy neologism: “longform,” they called it now, when it could fit on a quarter-page of newsprint. But we saw that certain niche media titles were succeeding amid the mass-market buckle, and we knew something else: that a culture remains vital thanks in part to systematic analysis, from writers not climbing career ladders and not beholden to sponsors. Art had grown more publicly visible than ever before, yet somehow it was understood worse — and between the tenure-track obscurity of a few publications and the vodka-sponsored vacuity of the rest, a vast center remained unoccupied. We asked around. We did our research. Readers were eager to join in the experiment, if they could find us, and writers were ready to fill the gap, if we could pay them.

We couldn’t name the thing for almost a year. In the initial production stages we’d chosen the meaningless codename Admiralty, out of the not wholly absurd conviction that liftoff, in an algorithmic age, would come more easily if we had a title beginning with the letter A. I spent countless days in libraries, combing art historical resources for inspiration, and all my ideas were bad. (For a solid week I was convinced the magazine should be called Alinhamento — “alignment,” in Portuguese — for no reason I can now recall.) I was so lost that my dumb idea to name the magazine with a string of random numbers was starting to seem not so dumb. At last my friend and colleague Zachary Woolfe, over improvised pasta one night, had the good sense to force me and Rebecca to rattle off as many essential works of modern art as we could name, and after passing over luncheons on the grass and damsels in Avignon, I spat out the signal artwork of the early 20th century: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, Marcel Duchamp’s enigmatic painting on glass, left “definitively unfinished” in 1923 and now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

That was the name, Zack proposed: just call it Even. Certainly it had resonance beyond the invocation of Marcel, my enduring Franco-American hero and art’s ultimate punster: it suggests evenhandedness, or an even tone; and there was the idea of getting even with, or at least evening out, a discourse we found stale. Yet the word “even,” or “même” in Duchamp’s original, introduces a bumpiness to the title both in English and French; the adverb can serve to modify either “bachelors” or “stripped,” but both in a slightly ungrammatical, imbalanced way. (There is also a theory that “même” is a pun on “m’aime,” or “[the bride] loves me,” but I don’t buy it.) Duchamp said in one interview that it had no strict meaning, and the word “even,” in this sense, is ironic. Grammatically, “even” should be clarifying the actions of bride and bachelors we see on the glass; in fact, it is the word that unhooks modern art from strict representation and lets it float in a realm of its own.

Crucially, Duchamp put the word “even” after a comma. The comma, that little dramatic/ironic pause, became our unofficial logo thanks to the design agency Common Name, whose principals Yoonjai Choi and Ken Meier we approached at the end of 2014. They had a brief to produce a magazine that was resolutely contemporary and yet not deaf to history, in a soft, handheld format whose dimensions were closer to a paperback than a glossy mag. Perhaps I should apologize to them here for the fanatical, self-contradictory mood board I made for them. (Me at my most neurotically unproductive: forgotten 70s literary journals, posters of unknown German regional theaters, close ups of individual letters of the logo of Barneys. The only concrete instruction I could offer was negative: “Not a Brooklyn food or foraging magazine!”) Somehow Ken and Yoonjai cut through the fog, and they designed us a magazine, and later a website, that deployed several old-fashioned elements — including the 17th-century Dutch serif typeface that serves as our body text — within uneven margins, in larger-than-expected sizes, and in bold, sometimes baffling colors. And they placed Duchamp’s half-absurd, ungrammatical comma smack on the cover: a punctuation mark that functions as a yield sign, a statement of intent. (To this day some readers hesitantly call the magazine “Comma Even” in speech. Really, no need to worry so much! We aren’t dogmatic; leave the overfussy punctuation to the architectural firms.)

Editing the first issue was...a learning experience? At the very least it was a bumpy ride, with false starts and beginner’s mistakes, many of them made at Rebecca’s kitchen table. My first planned cover story fell apart just a few weeks before deadline. The one we eventually published was fine, but I had to translate it from the writer’s native French. Our first major interview, with Luc Tuymans, almost didn’t happen at all; my train to Antwerp broke down between stations, I had to walk the tracks through the grimmest of Belgian industrial zones, and I made it to his studio with just minutes to spare.

I didn’t sleep much, but Even no. 1, its cover lime green, came together in time for the 2015 Venice Biennale, at which Rebecca and I trudged through the Giardini with hopelessly overloaded tote bags. The later issues grew more refined, and the production process got less (marginally less) hectic, but that first issue did contain the germs of an approach that became, over the nine issues to come, more like declarations of faith. One was a confidence that readers would stick with a review over eight pages, or an interview over sixteen, if they were written well enough, and if the magazine itself was designed handsomely enough, to justify the attention. Related was an insistence that good writing and serious thinking were not at odds: we wanted first-person narration, for example, to buttress historical knowledge and critical judgment, and not just serve as a get-out-of-expertise-free card. A third was a promise not to get distracted by the glossy surfaces of 21st-century high-tech, even as we also rejected the antimodern revanchism of “slow media,” back-to-nature hippiedom, and pour-over coffee. (As I said: not a Brooklyn food or foraging magazine!) We also trusted in writers with different kinds of expertise, many of whom, in later issues, would come from beyond the precincts of the self-defined “art world”: novelists, philosophers, ecologists, and in one case a sommelier.

The key commitment of that first issue was to think at global scale about contemporary culture, and to use the magazine to plot a more detailed, more accurate map of the world of art. That happened above all through our exhibition reviews — which were the part of art magazines Rebecca and I always found the most useless, a hangover from a lapsed time of exclusionary aesthetic judgment and slower media circulation. Nobody reads past the headlines of those 500-word reviews in the back of most art magazines. I used to write them and even I didn’t read them! We therefore, as we put that first issue together, asked a quartet of writers (in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and the US) to think about three or more shows in tandem, and to write something that would introduce readers to the larger stakes of culture at a certain place and time. We felt that the duty of criticism could only be fulfilled, this late in the game, by placing the exhibitions of the day within a much larger network of images, objects, and ideas.

One advantage of these omnibus reviews — beyond the bare fact that, years later, you might still want to read them — was that they allowed writers outside the art world’s more visible capitals to write for our proudly New York magazine on equal terms, and not have to humiliate themselves through the dreaded “city report.” (You know these if you spend any time on the art world’s lower-margin, click-hungry websites: “Why City X is the new Berlin”; “The 5 hottest galleries in City Y”; “Where to eat during the City Z Beanie Babies Triennial.”) Athens, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Delhi, the list goes on — and if I’m proud of one thing above all over these ten issues, it’s the geographical breadth Even brought to an artistic discourse that purports to be “global,” but too often betrays the laziest of frequent-flyer habits. When we devoted the lead story of our sixth issue to underground hip-hop in Luanda, Angola, it was neither willful esotericism nor the election of a next-big-thing. It was a statement of intent: if a writer as knowledgeable and as stylish as Chloé Buire could tempt you into the beachfront nightclubs of the most expensive city on earth, you would find contemporary culture with as much weight and urgency as anything in your hometown.

The 32 essays collected in this reader offer just a fragrance of Even’s ten issues. The extended interviews and artists’ portfolios are absent; the previews we published under the rubric Even More are absent too. But this book comes as close as I can to defining in miniature what Even stood for, and what we saw as culturally urgent in years of greater upheaval than we could ever have foreseen when we slogged through Venice in May 2015. Here we’ve thrown out chronology and geography both, and regrouped the magazine under half a dozen themes, from the shifting strategies of art institutions to the digital recasting of painting and, not least, the rise of rightwing populism in the US and abroad. These four years were momentous, hideously so in fact, and from a distance (who can say yet?), Even may endure less as a vehicle of critical judgment and more as a record of days of abandonment. Either way, we felt we had to say something, and to say it frankly. Critics don’t build monuments; we build time capsules, and that has to be enough.

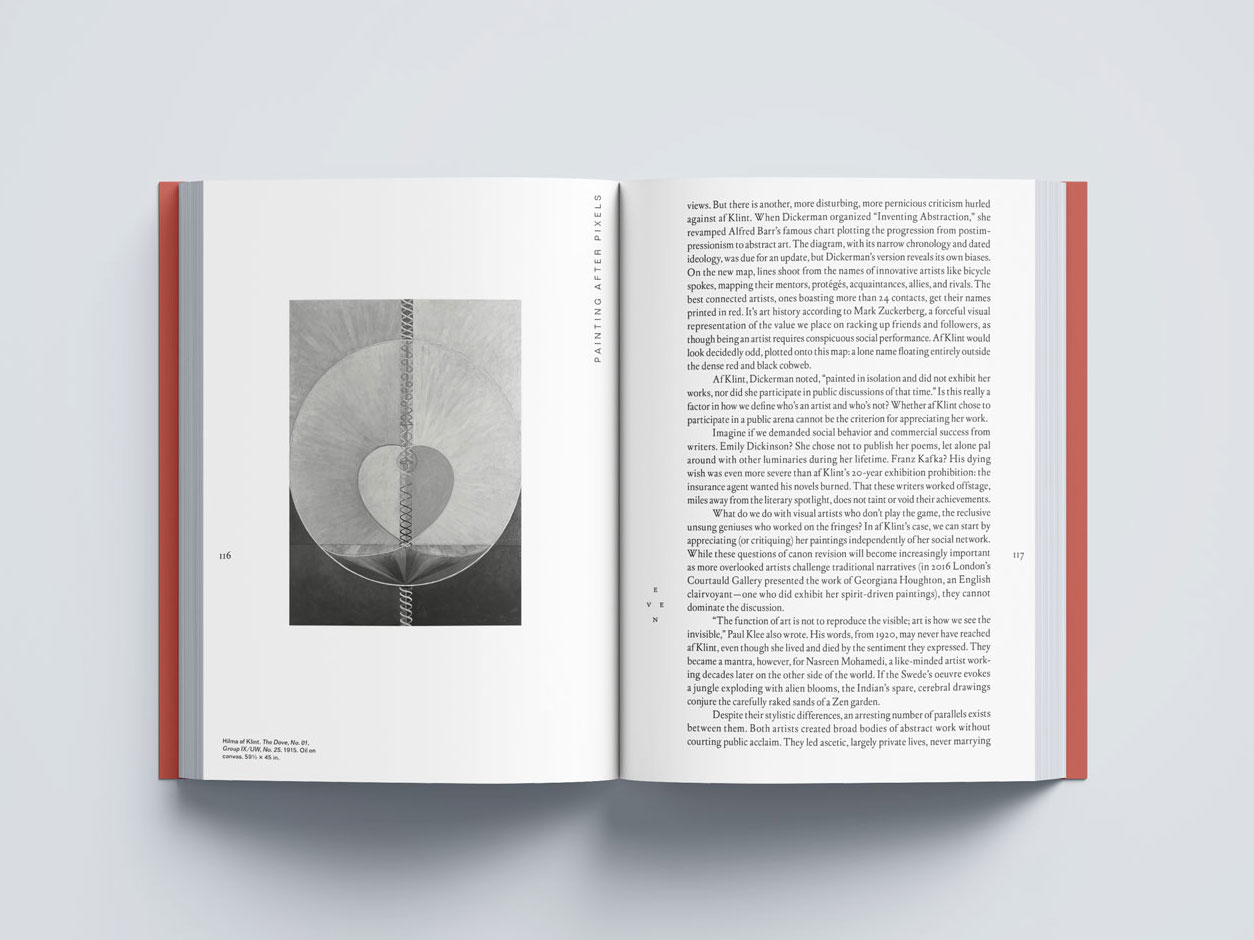

There can be no “Even generation,” as a little magazine might have mustered around its editorial line a century ago. We are too young, and have been on too many planes, to fool ourselves that a single avant-garde could form that way this century. But the writers whose work we’ve collected here shared with me Even’s gem-hard conviction that history was a material and not a limitation, and that we are not condemned, as the first issue’s editor’s letter had it, to prefix everything with re- and post-. They share that conviction with the younger artists I interviewed for the magazine or invited to produce portfolios — among them Camille Henrot, Ian Cheng, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Neïl Beloufa, Aslı Çavuşoğlu, and Lucy McKenzie — none of whom can be pinned down to a single style or even a single continent, but all of whom work in the historically minded present tense that Even was so avid to defend.

At last a magazine, especially one this size, is a collection of believers: people who stand by a project in fair weather and foul, and who convince themselves, against their better judgment, to undertake a journey that only goes uphill. First among our believers is Abby Sandler, Even’s indispensable majordomo and employee No. 1, who made sure every issue got out on time and later launched our podcast, Hidden Noise. Lynette Lee joined us as we completed issue 2; she went on to become associate editor and assigned several of the most powerful essays in this book, including an urgent report on architecture and urbanism in ruined Aleppo, Syria. Rachel Poser, our editor-at-large, had an eye for everything from Parisian fashion to Nepalese cave painting. At Common Name, Min Hee Lee became the coxswain of Even’s design team; much of the later issues’ good looks are hers. Several contributors to this book, strangers when I cold-emailed them, have become good friends, especially Thomas Chatterton Williams and James McAuley, in Paris, and Silas Martí, in São Paulo. My partner, Charles Aubin, had to play sounding board, proofreader, and amateur psychologist over the last four years; I owe him for more good turns than just these. And Rebecca Ann Siegel, the finest publisher any editor could ask for, is the author of this magazine’s adventure as much as me. More so, actually: she could do 90% of my job (and sometimes had to) while I could only do a shred of hers, and as she shuttled from boardroom to mailroom and back in the course of a day, she exhibited an acuity, a resolve, and a grace under pressure that any cultural institution would envy. One thing we writers often forget is how much better things can be if you trust someone else: if you get out from behind your desk, if you build something, even.