Build That Wall

by Thomas de Monchaux

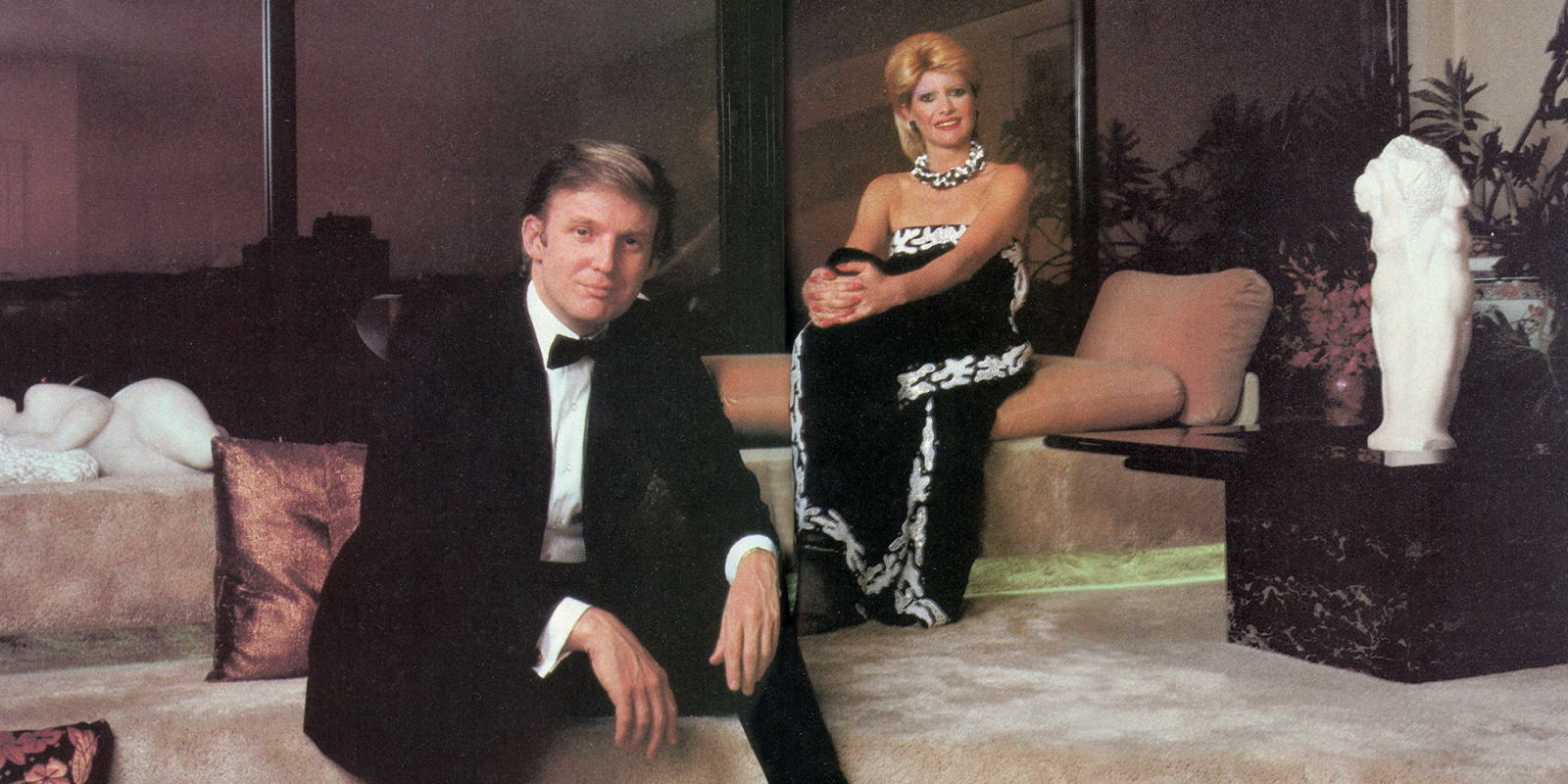

Donald and Ivana Trump in their apartment, designed by Angelo Donghia. Initially published in Town & Country, fall 1983. Photo: Arnold Newman.

This article appears in Even no. 5, published in fall 2016.

“He knows exactly who he is, and what he wants. He has very quick judgment and a very definite attitude about what he likes. With Donald, you don’t spend a lot of time wondering whether something is right or wrong — it’s (a) or it’s (b) and that’s that. And everything you do for him has to be done great.” That’s the interior designer Angelo Donghia speaking to Town & Country in 1983 about his most famous client, the then-37-year-old Donald J. Trump, for whom he decorated the well-publicized penthouse of the developer’s eponymous Fifth Avenue tower. While the low-ceilinged, three-level apartment continues the peachy-brassy, marble-and-metal look of Trump Tower’s public atrium, it adds a lining of gilded neoclassicism to the tasteful postwar modernism of the skyscraper itself.

For a specific boldfaced cross-section of New York — a clientele including Ralph Lauren, Diana Ross, Mary Tyler Moore, Woody Allen, Steve Martin, Halston, Liza Minnelli, and Barbara Walters — Donghia produced work that contained multitudes. Trump might have wanted (a) or (b), but Donghia often went for all of the above. To study photos of these luminaries’ Carter and Reagan-era apartments is to find our preconceptions of the styles of the late 70s and early 80s upended and mashed up — into decor that wasn’t especially decorous, and that complicated finesse with flash.

Sure, for Ralph Lauren he produced something that confirms our default impression of the “Me” Decade: a modernish uptown loft, all white walls and low, boxy custom sectional sofas under potted fiddle-leaf fig trees on pale herringbone floors. And sure, for his own New York residence he piled on patterns and textures with Louis-the-Whatever gold chairs in a way that satisfies our recollection of the go-go 80s’ pseudohistoricist excess. Yet in much of Donghia’s work, these two seemingly irreconcilable sensibilities, the minimalist and the maximalist, the futuristic and the elegiac, converge seamlessly in the same rooms. For his 1981 installation at the Kips Bay Showhouse, retro club chairs upholstered in metallic fabrics veer towards science fiction, but a breezy assortment of overstuffed ottomans and loungers are somehow rendered serene beneath a signature Donghia detail: a luminously reflective ceiling in tea paper, foil, or silver leaf.

Design history has never been a neat procession of styles. The juxtapositions of a transitional figure like Donghia — a man-about-town, a Parsons-educated tailor’s son given to the bold fabrics still produced under his brand — remind us that the story is always more complex. All the more so because, well before he found aesthetic synthesis in his designs, his life was cut short. Donghia died in 1985, aged 50, of AIDS-related pneumonia.

It’s poignant, given Donghia’s abbreviated body of work, that the images now most Google-algorithmically associated with the designer — present-day interiors of Trump’s residence — are only residually, if at all, his work. The background of Town & Country’s Arnold Newman photograph of Trump and then-wife Ivana does have that Donghia look: carpets turning corners, oversized cushions, metallic fabrics, unlikely stone artifacts, insouciant touches of both minimal and maximal. But just a few years later, a New York Times article about penthouse living identifies a Ross Malcolm MacTaggart as “a designer who worked on Mr. Trump’s triplex.” (The article goes on to quote MacTaggart’s lament that Trump’s “living room is blocked by the General Motors Building.”) Another intervening influence, in the traditional way, may have been the inclination of Trump’s successive wives to remove domestic traces of their predecessors.

Today’s incarnation of the Trump triplex — with its Rococo of pedantic pilasters and overhead frescoes, its involute topology of coves and coffers — seems too academic for Donghia. The easy conclusion is that, from the reflective ceilings to the gilded Corinthian capitals, a would-be Sun King eventually built himself a hall of mirrors, a pocket Versailles. Closer to the truth may be that a restless eye sought for itself a home that, detail upon detail, eye-catcher upon eye-catcher, provides constant diversion. The current Trump penthouse is a place for a short span of attention, a place without threat of stillness, a place where you don’t spend a lot of time wondering whether something is right or wrong. Ironically, the task of making such a place is not a matter of quick judgment and definite attitude, but is methodical, belabored, and slow — uncharacteristic of Donghia’s designs, whose studied nonchalance acknowledged that interior decoration, like that Of the Deal, is a fleeting Art.