January 2017

“Pictures,” Douglas Crimp’s 1977 exhibition at the New York nonprofit Artists Space, featured the work of only five artists. But soon a whole Pictures Generation had emerged: Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Sherrie Levine, and a dozen others, whose deconstructive photography veered from straight representation of the world to appropriated images of mass culture. James Welling was among that generation, and early on he shot close-ups of crumpled aluminum foil or velvet drapes in a photography studio: pictures that asked to be read as conceptual images, highlighting the rhetoric of photography itself more than whatever was in front of his lens.

James Welling. 0158. 2006. Digital inkjet print. 33¾ × 45 in. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London.

James Welling

SMAK, Ghent

Opens January 28

“Pictures,” Douglas Crimp’s 1977 exhibition at the New York nonprofit Artists Space, featured the work of only five artists. But soon a whole Pictures Generation had emerged: Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Sherrie Levine, and a dozen others, whose deconstructive photography veered from straight representation of the world to appropriated images of mass culture. James Welling was among that generation, and early on he shot close-ups of crumpled aluminum foil or velvet drapes in a photography studio: pictures that asked to be read as conceptual images, highlighting the rhetoric of photography itself more than whatever was in front of his lens. Then something shifted. He made similarly conceptual works, lush gradients of pure color, developed without a camera by exposing light-sensitive paper — but he also started shooting freight trains and railroad tracks, in a cool black-and-white that seemed straight out of the American documentary tradition. It turned out that the opposition between traditional representation and conceptualism was overdrawn. A photographer could critique modernism and follow in its path at the same time.

Welling, born in Hartford in 1951, had a youthful stint as a watercolorist; Andrew Wyeth, he of the grandly sentimental Christina’s World, was an early hero. Even at CalArts, where he studied under John Baldessari, he never trained as a photographer and had to master the formal elements of camerawork on the go. Maybe that helps to explain the double character of Welling’s photography, which always asks to be understood with both the head and the heart. Look, for example, at his Light Sources series of the 1990s: high-contrast photos in which lamps or neons flare to pure white. By design, they’re colder and more staid than the photography of an earlier American generation. Yet when you aggregate the photographs, you see in them not only a theoretical argument about light and image-making, but also a thoughtful gaze that’s emotional and all too human.

Welling’s most important insight was that conceptual sophistication did not negate, but rather reinforced, a photographer’s mastery, ingenuity, or good eye. Indeed, as affirmed by this extensive European retrospective (which tours to Vienna in spring), he has only grown more interested in technics, and his dozens of series of photographs make use of a similarly wide range of film, from crisp 35mm to large-format Polaroids. Though he does not shy from digital means — a recent show at Regen Projects featured groovy Photoshop overlays of dance photography and landscapes — it is via the simplest, most analog of technologies that he achieves the greatest power. At Philip Johnson’s Glass House, in Connecticut, Welling held before his camera a number of color filters: milky yellow, reedy cyan, and saturated red, turning the modernist house into an oneiric, even supernatural environment. In several, the sparkle of the sun through the filters produces spectra of red, green, and blue that appear like a gash over the image. That evidence of process, that evocation of the fundamental nature of light, would be an error by other, straighter photographers. For him it’s the whole point.

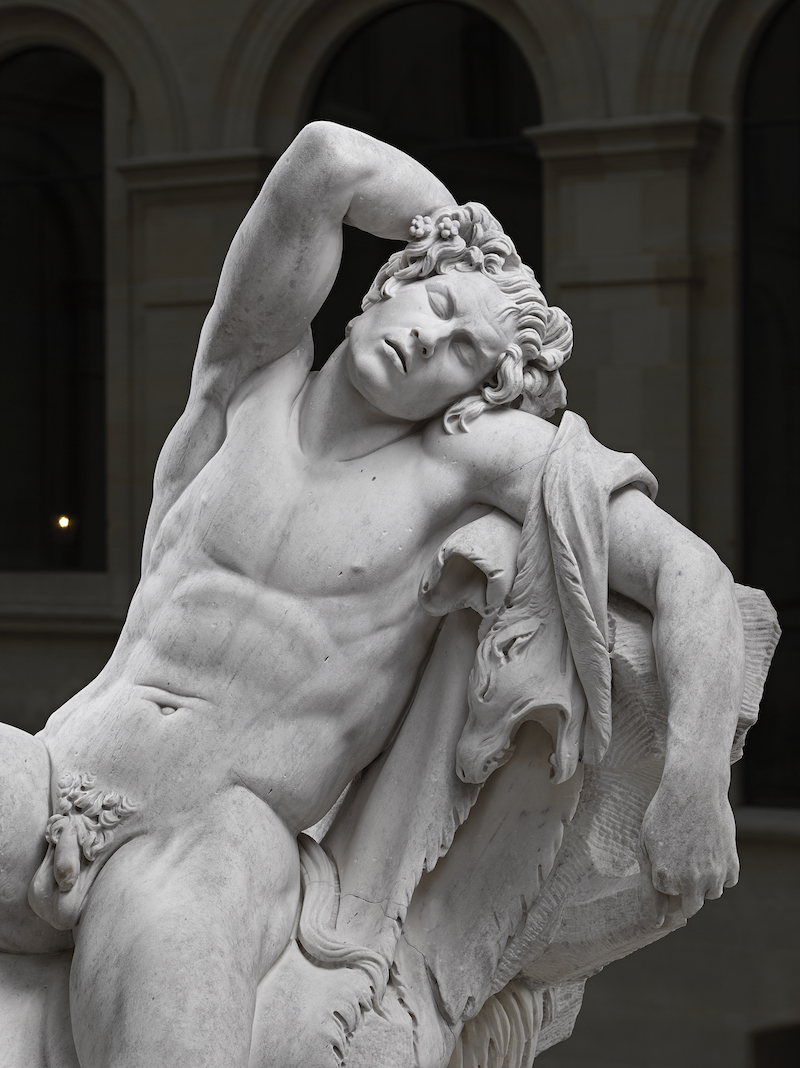

Bouchardon

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Opens January 10

Among his colleagues he was esteemed as one of the greatest artists of 18th-century France, but his sculptures — too neoclassical for the age's rococo tastes — found lackluster support in the court of Louis XV. The virtuosity of his pieces is undeniable (though his grand equestrian vision of that king was destroyed in the revolution), though his chalk drawings in striking deep carmine are as striking as his marble gods and heroes. Includes major loans from the Louvre and a Virgin Mary temporarily removed from Paris’s St. Sulpice Church.

Elizabeth Peyton

Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

Opens January 21

In the last couple of years, the New Yorker’s paintings on paper have become less delicate and drippier, and her excellent recent series of opera heroines have a Romantic disorder far exceeding her early fangirl pictures. This exhibition promises a full survey of paintings and drawings whose greatest virtue is their immediacy.

Opening of Museum Barberini

Potsdam, Germany

Opens January 23

A ho-hum impressionism show will inaugurate this heavily promoted new museum, which will house the collection of Hasso Plattner, the software billionaire. (He co-founded SAP, if you’re curious.) The bigger draw is the building, a reconstructed palace outside Berlin, and the permanent collection, which has a special focus in art from former East Germany.

Marisa Merz

Met Breuer, New York

Opens January 24

The only female artist to emerge out of Arte Povera has somehow gone unheralded for the last five decades; now at 90, she debuts her first US retrospective. Though Merz is still as private as ever, preferring art over people in her native Turin, here’s hoping she’ll no longer be overshadowed by her more famous husband Mario. Travels to LA in June.

Wade Guyton

Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Opens January 28

Did he birth a new age of digital painting, or did he just capitalize on his inkjet printer's propensity for paper jams? Guyton's saturated, computer-generated canvases have divided critical opinion, and now his Bowery studio has churned out new images and videos in the form cellphone snaps and screengrabs inscribed with his signature Xs, Us, and stripes.

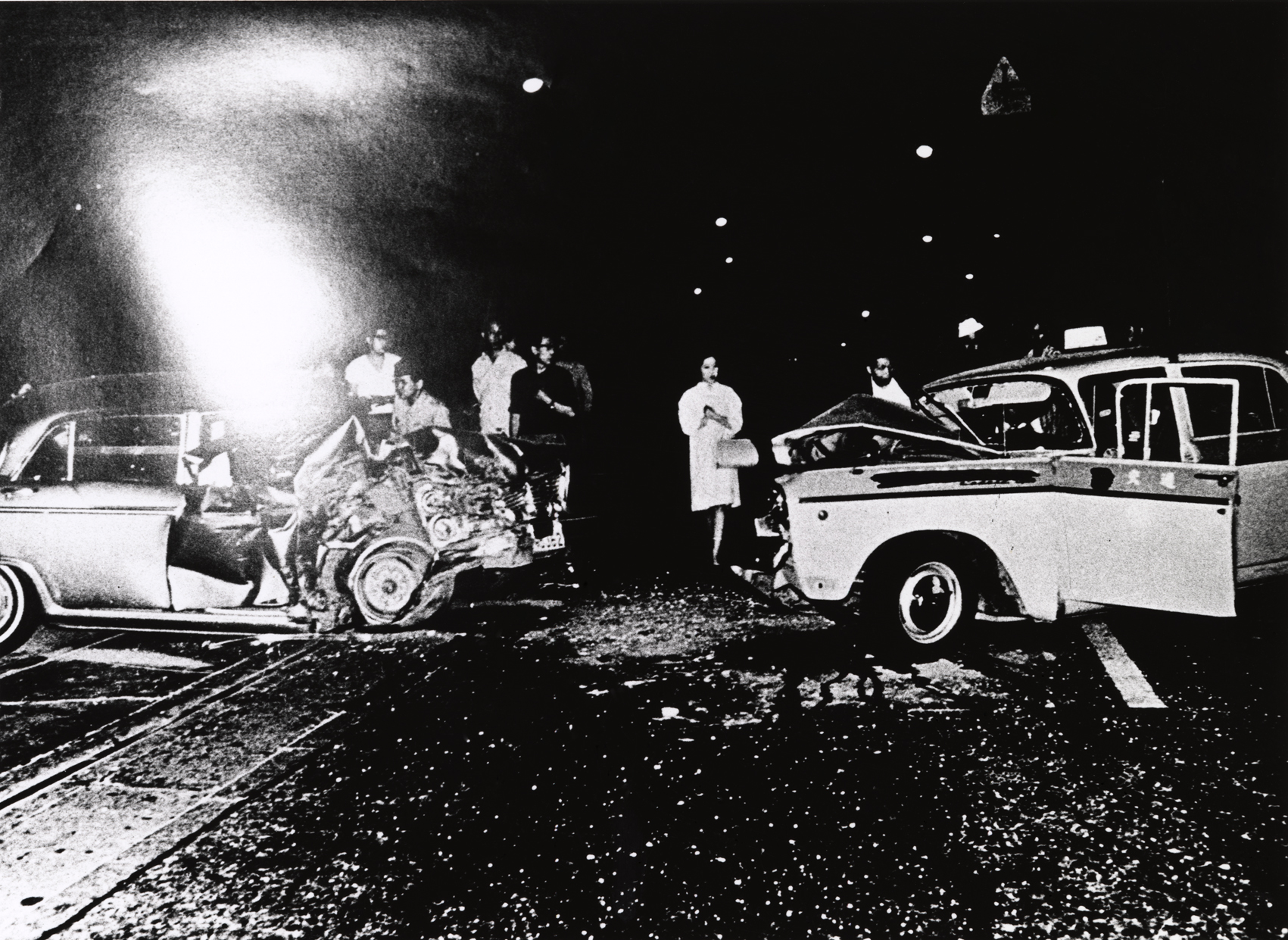

Provoke: Photography in Japan between Protest and Performance, 1960–75

Art Institute of Chicago

Opens January 28

First seen at three European museums — we saw it at Le Bal, the hip photography gallery in north Paris — this is the final stop for an epochal exhibition of Japanese photography, which looks at the work of Daido Moriyama, Shomei Tomatsu, and others in the orbit of a profoundly influential and shortlived magazine from the late 1960s. Provoke’s contributors favored a style called are-bure-boke — “rough, blurred, out of focus” — ideal for their shots of protesters, prostitutes, and Tokyo at night. If you miss it, there's always a 700-page catalogue.

Kapwani Kiwanga

Power Plant, Toronto

Opens January 28

Though she’s lived in Paris for a decade, Kiwanga is Canadian — and much of her art, including a trenchant documentary about gift-giving and international diplomacy, reflects her early training as an anthropologist. This show of new work builds on the young artist’s lecture-performances, collectively titled Afrogalactica, in which she portrays a scholar from the future who knows more about the present than we do.

Los Carpinteros

Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Belo Horizonte

Opens January 31

We've only just begun. But these Carpenters are no musical act; the Cuban collective make geometric and architectural wonders of wood-based objects (including traditional guitars) from their homeland. On view in this touring exhibition are 70 works from the last decade and a half, including new site-specific pieces.