October 2016

Mantua (robe and petticoat). British. 1748– 1750. Courtesy Fashion Museum, Bath.

The Vulgar

Barbican Art Gallery, London

Opens October 13

For three or four centuries after the fall of Rome, scholars and theologians in their drafty studies kept writing in a language that they did not speak — and that their neighbors and servants found impenetrable. In the scriptorium, the lingua franca was still Classical Latin, with its myriad case endings and unrestricted word order. The street, from Seville to Sicily and Tunisia to Constantinople, used an unwritten, less inflected language, the language of the vulgus: the mob. Thumb through the writings of early Christian academics and you’ll find endless apologies for Vulgar Latin, and grumpy complaints that its plodding style and infelicitous new words were gumming up the holy texts. But who could read them? The mob would win the day, as their language branched into French, Italian, and half the other tongues of Europe. To be vulgar was to be useful.

Vulgarity is an easy slur to lob from up high, but the people know what they like, and there has always been a market for spangles and crinoline, gold lamé and jeggings. Yet “The Vulgar” — spanning five centuries of western fashion history, and curated by the fashion scholar Judith Clark and the author and child psychologist Adam Phillips — will be one of the first substantial exhibitions to look at the history of uncouthness, and to investigate just when and how bad taste becomes good. (Irksomely, it opens the week after Frieze Art Fair, which has been moved forward this year.) Manuscripts, textiles, and historical costumes, such as an 18th-century dress whose eight-foot overskirt could be confused for a card table, will be interwoven with newer forays into vulgarity. Contemporary designers are also in the mix, among them Vivienne Westwood, Viktor & Rolf, the milliner Philip Treacy, and above all Walter van Beirendonck: the brashest of the Belgian fashion designers known as the Antwerp Six, who sends emaciated boys down the runway wearing skirts made of bubble wrap and ivy-festooned trucker hats. But vulgarity can be its own sort of elegance. For decades, Fratelli Prada was a discreet, moderately profitable Milanese leather goods specialist. It was a nylon bag, designed in 1985 by Prada’s Ph.D.-holding granddaughter, that made the world take notice.

Is vulgarity, and for that matter sophistication, just a matter of taste? In higher mathematics, it’s not enough just to prove a theorem; you have to prove it elegantly, that is, in a succinct and surprising way rather than via brute force. Art today relies on a similar know-it-when-you-see-it definition, but we are far more hesitant to proclaim as much; depending on the day, the vulgar might be held in higher esteem than the exquisite. (A few years ago, New York witnessed a mercifully lapsed vogue for something called “retarded painting.” We hope you didn’t buy any.) An age in which sales or clicks are the highest form of approval is by definition a vulgar one, but even elite art discourse struggles today to agree on whether anything, besides popularity, might make the merely pretty into something great. In that light, “The Vulgar” promises to be more than a fashion show, but a negotiation of the peskiest tripwire of contemporary culture: whether we all still share any principles of aesthetic judgment.

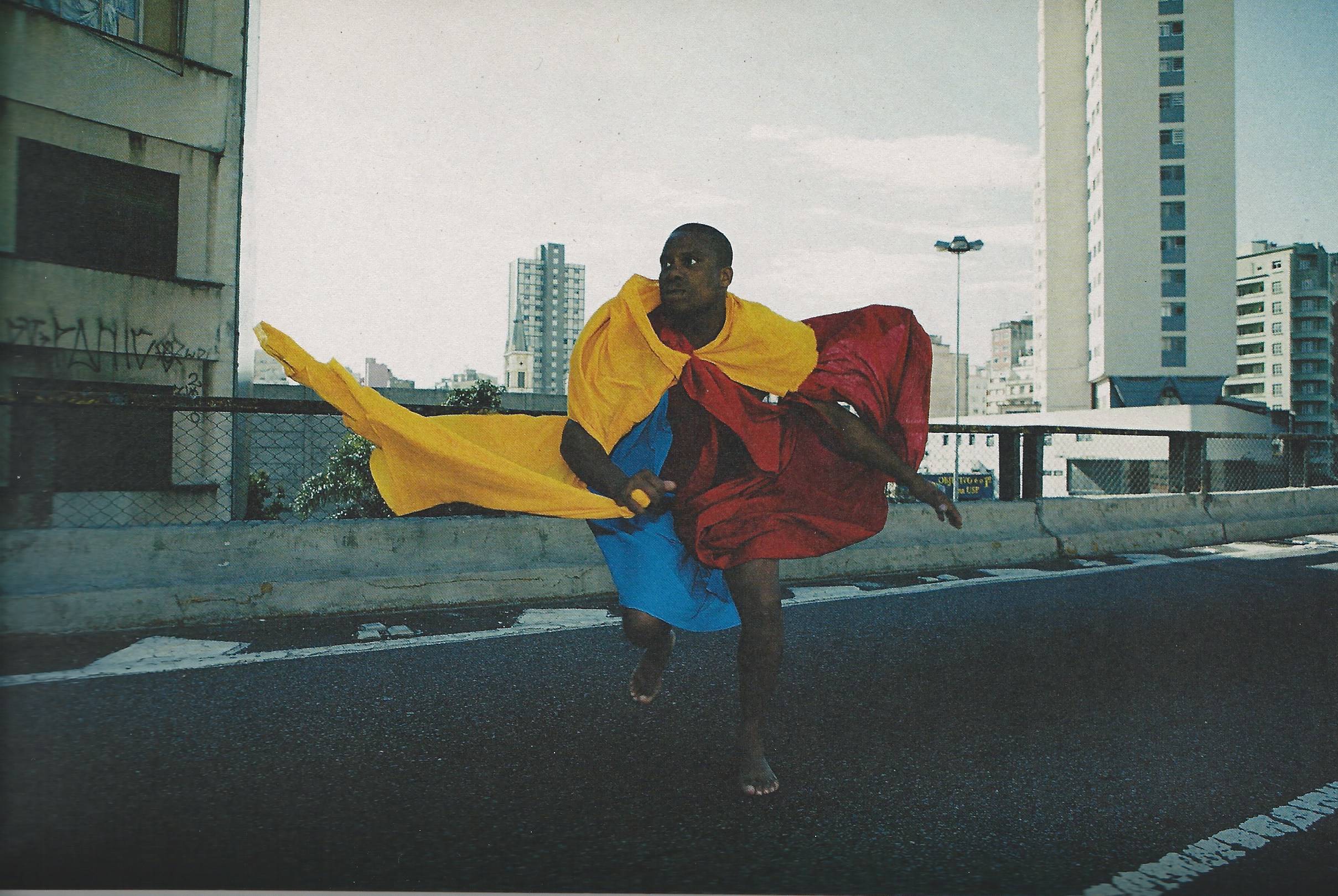

Hélio Oiticica

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Opens October 1

A very big deal: this is the first full-dress retrospective in the United States for the artist who best mapped Brazil’s tyranny and hedonism. After the hot-colored, geometric compositions of his concretist phase, Oiticica in the 60s embraced the counterculture through the ornery, wearable capes he called parangolés, not to mention dictatorship-denouncing flags and drawings made with cocaine. Travels to the Whitney and the Art Institute of Chicago next year.

Picasso/Giacometti

Musée Picasso, Paris

Opens October 4

The Spanish hothead, in later life, respected very few artists, but one was a Swiss sculptor two decades his junior, whose extruded humanoids are as severe as his are boisterous. Where Picasso favored confrontation and virtuosity, Giacometti was all about silent presence — which should make an interesting contrast in this two-hander, a promising successor to MoMA’s blowout “Picasso Sculpture” of last fall.

The City in Art, Art in the City

National Museum of Korea, Seoul

Opens October 5

Earlier this year Kim Young-na, the esteemed director of one of the world’s largest museums, was unexpectedly fired — allegedly for balking at a touring exhibition of commercial French fashion supported by the president’s office. This show, looking at depictions of urbanization and at Seoul’s progress from backwater to megacity, is one of the first major openings since at an institution keen to get back to proper art history.

Krzysztof Wodiczko and Jarosław Kozakiewicz

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw

Opens October 6

The two Polish artists and veterans of the country's Venice pavilion — one of the art biennale, the other of the architecture event — reimagine the future of disarmament in their proposed Józef Rotblat Institute, named after the physicist who vacated the Manhattan Project on moral grounds. In their critique of contemporary war culture, Wodiczko and Kozakiewicz will also set out propositions for the construction of an anti-war monument.

Carlos Motta

Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

Opens October 14

The multidisciplinary Colombian artist, fresh off a bondage-and-religion performance earlier this summer in Vorno, Italy, looks at theological testimony on gender and sexuality. Of particular interest is liberation theology, a doctrine focused on the religious experience of the poor (and embraced by Pope Francis), but here Motta applies a sexual, rather than social reading.

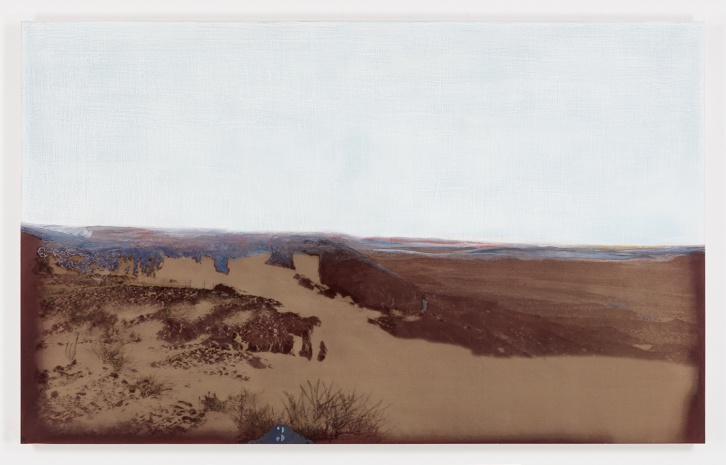

R.H. Quaytman

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Opens October 16

In an era emphasizing the personal and the noncontextual, Quaytman’s paintings are displayed in contextually referenced “chapters”, so that pieces are site-specific and bodies of work are successive and connected. At MOCA this month is her first institutional survey, which forms the 30th chapter of the project she began 15 years ago.

Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910–1950

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Opens October 25

Mexico’s growing pains during its modern and revolutionary years are countenanced in these colorful, vividly rendered paintings, and the famed murals of los tres grandes — David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco — are digitally transported to museum walls. This is the most comprehensive stateside exhibition of Mexican Modernism in memory; see it before it travels next year to Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in the DF.

Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Opens October 28

Chrissie Iles’s high-stakes exhibition examines a century’s worth of envious glances between art and cinema, and the transformed presentation of moving images in the white cube. Along with Pierre Huyghe, Liam Gillick, and other artists who reintroduced cinema to the gallery in the 1990s, the show will feature a major work from Ian Cheng, interviewed in Even no. 4.