Exit Ghost

by Laura McLean-Ferris

To describe the art world’s prevailing reaction to Britain’s vote to leave the European Union, you need to step out of the language of party politics and into the language of grief. Because true politics deals in emotions, after all: a theater of hope, fear, love, and anger.

Sutton Hoo helmet. Anglo-Saxon, early 7th century. Iron and tinned copper alloy.

12½ × 10 × 8½ in. British Museum, London.

This article appears in Even no. 5, published in fall 2016.

To describe the art world’s prevailing reaction to Britain’s vote to leave the European Union, you need to step out of the language of party politics and into the language of grief. Because true politics deals in emotions, after all: a theater of hope, fear, love, and anger. Even before the referendum of June 23, I found myself in horror-struck tears at the xenophobic language of the Leave campaign, which all too inevitably fed into the murder — in broad daylight — of Jo Cox, the Labour MP who campaigned for Remain. A few days after the vote, having traveled through at least three of the five stages of grief, I went out following a New York gallery opening and found myself drinking with real purpose. I had entered a phase of self-questioning and criticism, queasy from the misunderstanding and condemnation of Leave voters. At drinks I’m talking with a few artists and curators about the inequality that bolsters the art world in London, which has become ever more detached from the rest of Britain — and in the referendum, while every English region voted to leave, London (like Scotland and Northern Ireland) voted overwhelmingly to remain. I know the argument coming out of my mouth sounds terrible. I can’t actually say cosmopolitanism because I am slurring my words. And yet something sticks; something feels wrong, unfair, an expression not of conviction but of mourning.

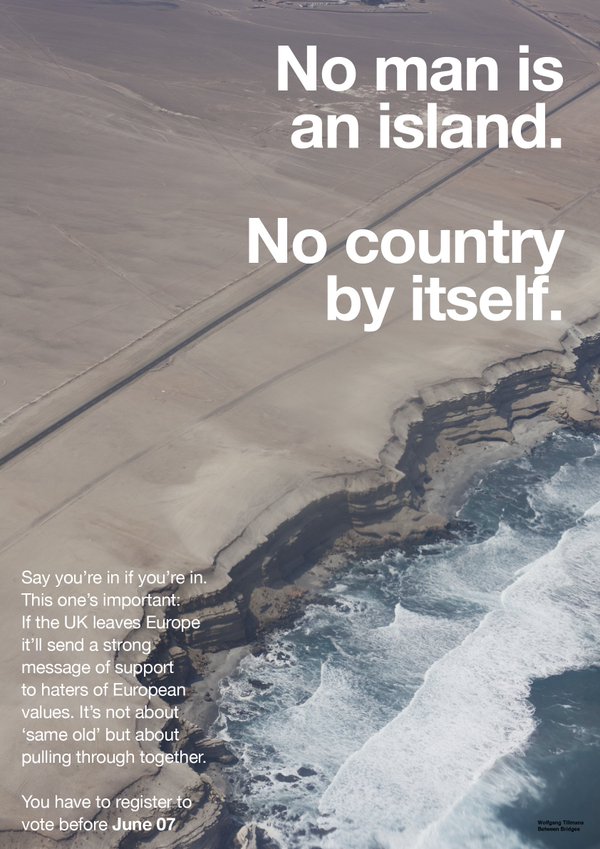

In the immediate aftermath of Brexit, reactions from writers and curators were uncharacteristically impetuous and emotive. Those of us who have to negotiate the complex terrain of art world relationships often shy away from alienating absolutes. But a storm of rage passed over, in which individuals berated each other for thinking the wrong thing. (Here’s the artist Ryan Gander, writing a day after the vote: “The majority of the British public do not have enough of a grasp of economics, politics and social mobility to be trusted to decide the future of the country.… I am ashamed to be British.”) As the markets tanked and the country’s leadership became a diabolical shambles, there were other, more sober, art world contributions. The artist Liam Gillick wrote in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on the subject of Brexit. He berated the “cultural mainstream” for failing to come up with anything better than “I ♥ EU,” “Better Together,” and a collection of Damien Hirst pro-unity butterflies. (Wolfgang Tillmans, whom Gillick called “heroic,” did attempt to fill that gap: his free posters for Remain, one of which was captioned “What is lost is lost forever,” were distributed widely online.) The curator Sohrab Mohebbi, responding to Gillick, zeroed in on the art world’s more frequent style of political gesture: a self-awareness that dramatizes, rather than contests, our implication within a toxic system of production, wealth, globalization, exploitation, gentrification, and so on. He doesn’t name any artists, but maybe let’s say that this could include everything from Andrea Fraser’s important 2011 essay “L’1%, C’est Moi” to this year’s Berlin Biennial, curated by the cheery capitalist-realists DIS. This is a form of reflexivity, Mohebbi writes, which “has become the basin where artists and institutions merely wash their hands clean and walk to the vernissage dinner self-content.”

Underpinning both of these responses is an inability for artists and art spaces to come up with anything particularly affirmative in the face of a no-alternative economy and the rightwing demagoguery that delivered a win for the Brexiteers. Empty glass investment towers in London have blossomed, while the north and Wales sink deeper into poverty; both of those regions actually received significant European funding, and will find themselves even more defenseless against the austerity budgets of the new May government. We may be reaching a rhetorical and emotional breaking point as the country claws at itself, and handouts don’t beget gratitude. The xenophobia of Leave voters has a counterpart in those who objectify and minimize the people who disagreed with them: it’s the white working class, it’s the chummy middle class, the racists, the undereducated, those workers who were betrayed by Labour. It’s a cry of pain, it’s a howl in the dark.

One of best arguments for therapy, I believe, is that you can’t see the walls of your own mind because they’ve been built for you by other people. This would seem to apply somewhat to your sense of national identity, too. The Britain I thought I knew was never comfortable with nationalism, but I must have had a sense of nationhood, or I wouldn’t have felt such grief when it wasn’t what I thought it was. In my mind, one of the things that “Britain” named was a certain openness and weirdness — a workaday sort of diversity, an ecology in which queerness and eccentricity had flourished in certain good moments. And these attributes, combined with a market, have created an important, internationally appreciated generation of British artists.

On my most recent visit to London, in town to curate a project for the ICA, I arranged to meet my family at the British Museum. I was looking for England, I think, as my family is Scottish, and my connection to England suddenly seemed very weak. I stopped in Room 41, refurbished and reopened in 2014, which displays the Sutton Hoo burial — an enormous, regal Anglo-Saxon ship dating to around AD 600. It’s one of the greatest archaeological discoveries in Britain, partly because, when it was unearthed in Suffolk during World War II, so little was known about the so-called Dark Ages. The boat was filled with finely crafted treasure: silver brooches, cut glass, necklaces. A sword was etched with patterns resembling moving water or a circuit board. There were snake designs on a gold belt buckle; a maplewood lyre; a purse covered with wolves, their eyes marked with garnets. On that day, in a country I once knew, I was struck by the artifacts of a people who had been radically misunderstood by history, relieved of the label “barbarians” when a ghost ship was dug out of the ground. For us now to see one another as more than philistines will take another, no less necessary sort of archaeology, a dig deep into the quarries of our divided selves.