April 2016

Hello! Welcome! It’s a beautiful show, isn’t it? You can always expect a nice greeting from the art of Andrea Fraser, which interrogates the details and distinctions of the art world with a beaming smile — before going in for the kill. Fraser is the ardent successor of a generation of artists whose querying of museums and their procedures came to be known as “institutional critique”: Hans Haacke, say, who polled visitors to MoMA about their income and political views, or Daniel Buren, whose unvarying stripes exposed how the museum directs attention and turns mere pictures into works of art. Fraser, in turn, examined not art’s spaces but its languages, and probed the discourses that museums — not to mention art magazines! — use to legitimate art, and themselves. In Official Welcome (2001), she mercilessly parroted the prattle of gallerists, donors, and taciturn artists, all giving the same toasts on the art world’s never-ending cocktail party circuit. (“He may be obsessed with death,” says Fraser, channeling some dumb dealer, “but only because he has such an incredible passion for life.”) Performances were followed by videos, in which art and politics got mixed up with sex. In Little Frank and His Carp (2001), Fraser listens to the Guggenheim Bilbao’s ludicrous audio guide and becomes uncontrollably turned on. Then came Untitled (2003), which dramatized the workings of the market in a peculiar way: she fucked a collector on camera, and sold the video in an edition of five.

Andrea Fraser. Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk. 1989. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne.

Andrea Fraser: L'1%, C'est Moi

Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona

Opens April 21

Hello! Welcome! It’s a beautiful show, isn’t it? You can always expect a nice greeting from the art of Andrea Fraser, which interrogates the details and distinctions of the art world with a beaming smile — before going in for the kill. Fraser is the ardent successor of a generation of artists whose querying of museums and their procedures came to be known as “institutional critique”: Hans Haacke, say, who polled visitors to MoMA about their income and political views, or Daniel Buren, whose unvarying stripes exposed how the museum directs attention and turns mere pictures into works of art. Fraser, in turn, examined not art’s spaces but its languages, and probed the discourses that museums — not to mention art magazines! — use to legitimate art, and themselves. In Official Welcome (2001), she mercilessly parroted the prattle of gallerists, donors, and taciturn artists, all giving the same toasts on the art world’s never-ending cocktail party circuit. (“He may be obsessed with death,” says Fraser, channeling some dumb dealer, “but only because he has such an incredible passion for life.”) Performances were followed by videos, in which art and politics got mixed up with sex. In Little Frank and His Carp (2001), Fraser listens to the Guggenheim Bilbao’s ludicrous audio guide and becomes uncontrollably turned on. Then came Untitled (2003), which dramatized the workings of the market in a peculiar way: she fucked a collector on camera, and sold the video in an edition of five.

The allegedly free terrain of contemporary art, Fraser insisted, in fact has rigid rules. The putatively transgressive avant-gardes in fact posed no risk at all to the governing order. Fraser is now 50, though, and not only have her soundings of the art world won total approbation by the institutions she critiques, but the very concept of critique no longer seems newsworthy — this winter, Walid Raad lambasted whole swaths of the art market right in the MoMA atrium, to no great scandal. In the past, Fraser seems to have understood that such absorption was inevitable, and could be spun for good or ill. “It’s not a question of being against the institution,” she wrote in 2005 (she is, rare among artists, a truly great writer). “We are the institution. It’s a question of what kind of institution we are, what kind of values we institutionalize, what forms of practice we reward.” But recently Fraser has exhibited far less, demoralized, she freely admits, by the enduring divide between the art world’s haves and have-nots. A brief appearance at the Whitney in New York, in which the gallery was left empty and occupied only by carceral sound recordings, is the closest she has come in recent years to a major new work.

It’s not child’s play to organize a Fraser exhibition, both because of her art’s bite and its site-specificity. Last year’s outing in Salzburg was well received, but the stakes of this show in Barcelona are higher. For last March, MACBA abruptly cancelled the opening of its exhibition “The Beast and the Sovereign” after the museum’s director objected to the inclusion of a sculpture by the Austrian artist Ines Doujak, which depicted the former king of Spain being — no point sugarcoating this — sodomized on a bed of SS helmets. After huge outcry the show eventually opened, with the sculpture included, and the director resigned. MACBA thus offers a rare opportunity for Fraser to capitalize on her latterly anxieties about art and its public. Participation, she has shown us for years, does not mean accepting all of an institution’s premises, and Fraser may well reclaim for critique the urgency it still demands.

Yasumasa Morimura

National Gallery of Art, Osaka

Opens April 5

This is the first hometown institutional retrospective for Morimura, the self-described “conceptual son” of Warhol, whose jesting self-portraits feature the gender-fluid chameleon as various icons within canonical artworks. But while his drag acts can seem dimly crowd-pleasing at first, the real virtue of Morimura's art is its dismantling of the pieties that still attend western art history, and its insistence that European art is the whole world's inheritance to reboot as it wishes.

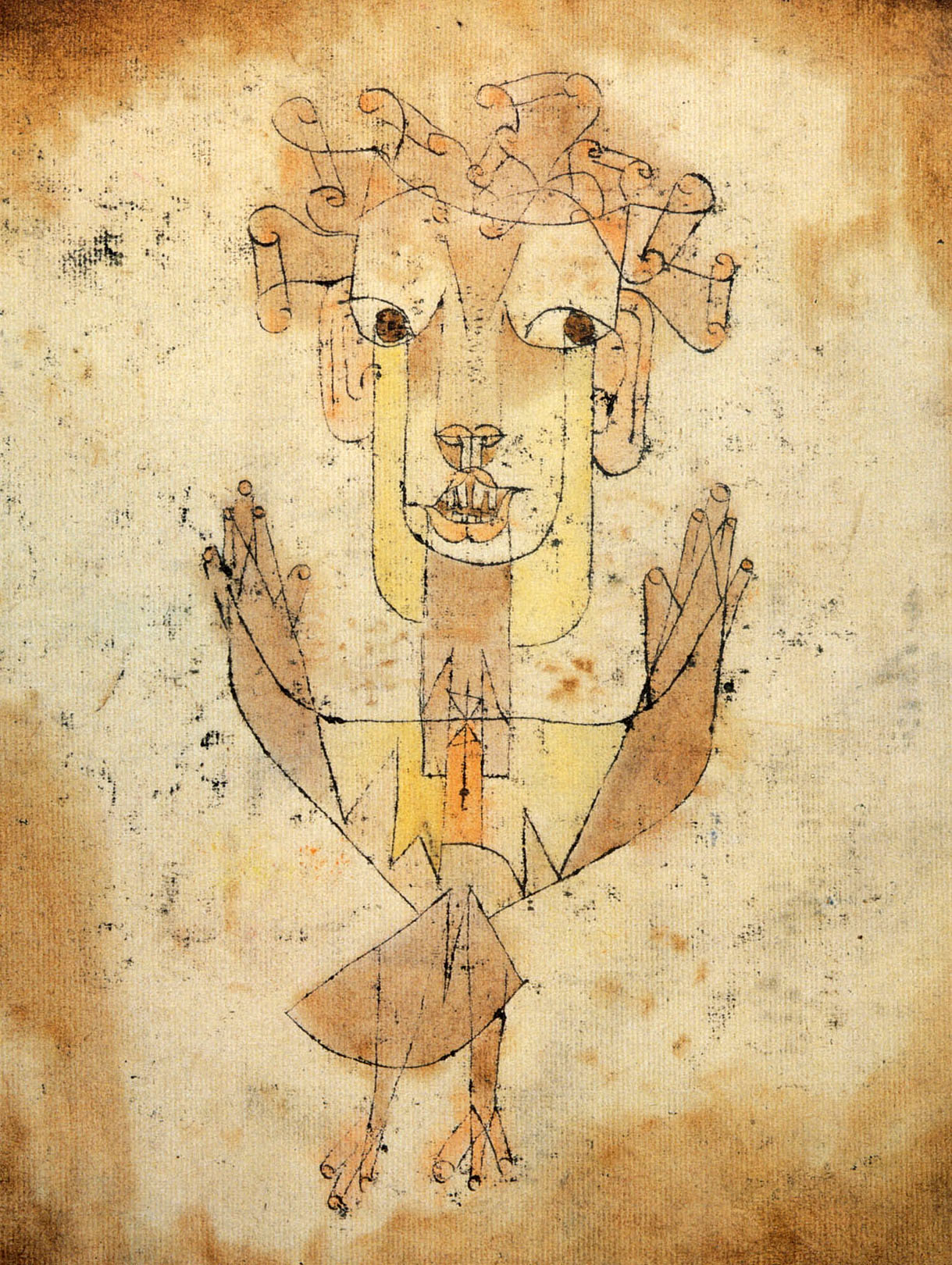

Paul Klee: Irony at Work

Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Opens April 6

It hasn’t even been three years since the Tate’s massive Klee retrospective, and we’re not exactly sure why this one is happening, but the Pompidou’s showcase of the Bauhaus veteran includes one of the rare artworks we can properly call mythical. Many of the 250 works are coming from the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, but the biggest prize of all has been loaned from the Israel Museum: Angelus Novus (1920), his meandering oil transfer drawing of a floppy-mouthed, curly-haired angel, envisioned by its previous owner Walter Benjamin as the angel of history.

Glasgow International

Tramway, Gallery of Modern Art, and elsewhere, Glasgow

Opens April 8

This reliably strong biennial is the last edition helmed by the formidable Sarah McCrory, and offers the perfect excuse to head up to what remains (sorry, Peckhamites) Britain's most important city for contemporary art. Among the highlights this year: a showcase by Cosima von Bonin of sculptures and videos featuring only creatures of the sea, and a typically color-saturated exhibition by the prodigiously inventive fiber artist Sheila Hicks.

High Society: The Portraits of Franz X. Winterhalter

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Opens April 17

German-born and Paris-based, Franz Xaver Winterhalter was the Annie Leibovitz of two centuries ago, painting flattering portraits of 19th-century European nobility in poised revelry. So popular was he that academic circles shunned him, even while his favor grew in the heady days of the Second Empire. In a very Houston move, this show presents Winterhalter’s glamorous subjects alongside the period’s dramatic haute couture — think satin, crinoline, the works.

Liu Xiaodong

Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

Opens April 22

As indebted to Courbet and 19th-century French realism as to the Chinese tradition of xiesheng, or “painting from life,” Liu paints at his travels, living among his subjects for months at a time. Liu spent much of the last year in Italy, not only in Florence but in the Sienese countryside, and the new paintings here portray the everyday lives of Chinese immigrants in the half-light of one of Europe’s tourist meccas.

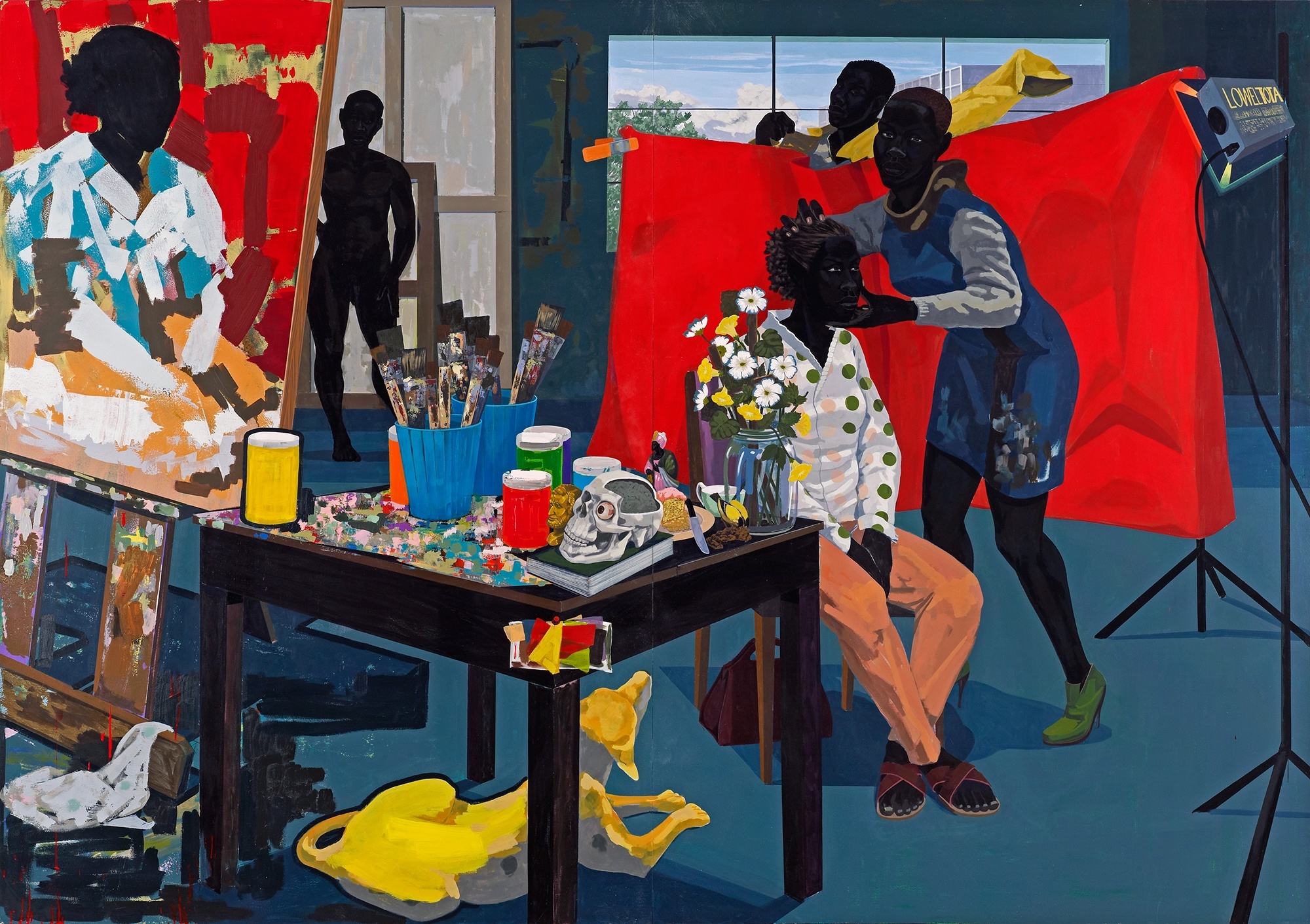

Kerry James Marshall

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

Opens April 23

His imposing figurative tableaux, with black Americans unapologetically foregrounded and uniformly dark-skinned, revive and re-circuit a long tradition of history painting left for dead in the 20th century. But Marshall has always been engaged with more than just the past: his masterful abstract Blots were some of the finest paintings in Venice last year. This major survey starts in Marshall’s hometown, then tours in October to the Met’s new outpost in the Whitney’s old Marcel Breuer building, and finishes at MOCA in LA.

Avery Singer

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Opens April 23

Just six years out from Cooper Union, this native New Yorker has made waves with institutional solos at Kunsthalle Zürich and the Hammer Museum, as well as a much-lauded installation at Art Basel last year. At the Stedelijk, Singer will be presenting four years worth of her monochrome assemblages of geometric figures and objects. In these seemingly simple works, process is key — each piece is modeled with software and digitally manipulated before she applies layers and layers of paint.

Cally Spooner

New Museum, New York

Opens April 27

The young British artist is an ironist of sound, crafting recordings and performances whose librettos intermesh PR babble, celebrity schmaltz, and the effluvia of online comment sections. After her operatic occupations of the Tate and the Stedelijk, this performance will riffs on the corporate character of the New Museum’s glass-walled lobby gallery, rather easily imagined as the break room of a mid-tier insurance company. We’re told Spooner is planning to pump up the heat as well, turning the white cube into a pressure cooker.

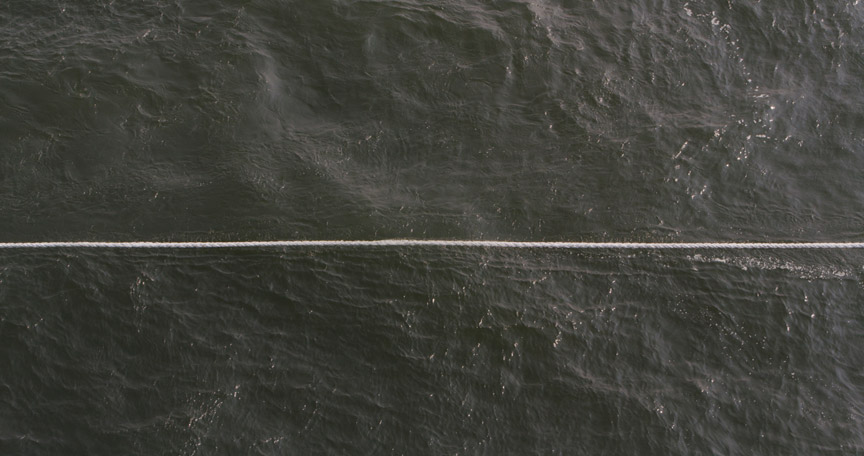

Charles Lim: Sea State

NTU Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore

Opens April 30

Lim represented Singapore at last year’s Venice Biennale, but he has been at grander international events than that: he’s a former Olympic sailor, and the water around his home has served as both metaphor and backdrop for his investigations of nation-building and economic history. This final phase of a decade-long project, comprising a super-hi-def film and documentary materials, looks at climate change and land reclamations in a city-state that takes social engineering to extremes.