Paris When It Sizzles

by Thomas Chatterton Williams

Olafur Eliasson. Ice Watch. 2015. Place du Panthéon, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo.

This is an excerpt from Even no. 3, published in spring 2016.

During the last two months of 2015, two very different visions of apocalypse — perhaps always latent in the globalized, hyperconnected background — gathered and crystallized in Paris. If only temporarily, they proved impossible to ignore. There were of course the horrific, coordinated attacks of November 13, which left 130 dead and even more wounded at café tables and in a popular concert hall. Appalling as it was, the atrocity was at least intelligible, the latest awful act in what Pope Francis has called “a piecemeal World War III,” skirmishes of which have since broken out in San Bernardino, Brussels, and Philadelphia, not to mention Beirut and Baghdad and Jakarta. But there was something else, too: the stubborn, unnerving intimation of a greater menace that with each passing season becomes harder to deny.

Paris, in late 2015, was also a hotbed of environmental anxiety, as the city geared up to host the most anticipated climate conference in years. This past year was the hottest in recorded history, and the 19th in a row whose temperatures exceeded the last century’s average. There have been enormous rains and floods in India, Britain, and the US, not to mention forest fires and tornadoes, landslides and hurricanes, in too many places to name. Temperatures have been so unseasonably high this year that the North Pole rose above freezing in December for only the third time since 1948. My family spent Christmas in New York, and on the 25th of December the city hit 75 degrees Fahrenheit. When I asked the owner of the wine shop near my brother’s apartment why she had so many bottles of rosé on prominent display, she shook her head and told me they were selling as if it were the 4th of July.

And yet the mind proves its resilience. For better or worse, it is impossible to remain on high alert, and the world insists on feeling like a comfortable place to live. Almost immediately after the attacks, the café terraces filled again and, despite a definite lingering edge, the fear could not help but fade away. My wife and I live in the next arrondissement from Le Carillon and Le Petit Cambodge, and as I waited the 20-minute eternity for her phone call to let me know she was all right, I was held in the contours of my own personal apocalypse. Yet such an intensity of feeling or even awareness cannot hold. I remember the courageous normalcy of neighbors and merchants in the bakery the following morning, and then the stroll home from a friend’s house later that evening, through desolate streets. What I remember most was the unsettling feeling of working up a sweat that November night. It was, like Christmas in New York, unseasonably warm.

Olafur Eliasson, the Danish-Icelandic artist whose large-scale projects often make use of elemental materials, has spent his career challenging us to rethink the ways we see and interpret weather. On December 3, on the circular plaza just in front of the Panthéon, he oversaw the installation of Ice Watch, a sculptural collaboration with the geologist Minik Rosing. The artwork comprised a dozen large blocks of ice formed from thousands-of-years-old snow, which had calved off glaciers near Nuuk Harbor, in the waters off Greenland. Taken together, the blocks weighed nearly 100 tons, and formed a circle 65 feet in circumference. The weight of the ice itself was a statement: it is the same amount that now melts worldwide every hundredth of a second. The circular formation, in case the message still wasn’t clear, represented the face of a ticking clock. (Ice Watch was meant to be installed at Place de la République, the giant square just up the road from the Bataclan; after the attacks the project was relocated to the left bank.)

To call it “art” is generous. Ice Watch was advocacy, a visual pamphlet able to be summarized and hashtagged without sacrificing any ambiguity or meaning. The world’s glaciers are shriveling right in front of us; time is running out; even our best minds look passively on. This is not an entirely new idea for Eliasson. Already presented in Copenhagen last year, it’s a more visible and better-looking rehash of his 2013 MoMA PS1 installation Your waste of time, which brought huge hunks of ice from Iceland’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull, to Queens (though unlike with Ice Watch, the galleries of PS1 were refrigerated to keep them from melting). The ice in the PS1 show originated sometime around AD 1200; younger than the glaciers brought to Paris, but still so old as to exceed understanding.

We simply don’t live long enough to form meaningful firsthand perspectives on matters as monumental as climate change — or, at least, we haven’t yet. If anything, Ice Watch (and, to a lesser degree, Your waste of time before it) amounts to a brutally effective advertisement of our impotence. Because it invites and even demands our interaction, it cannot help but reveal who we really are, what we value, how we cope with unbearable truths. And how we cope with such truths, it certainly seemed on the afternoon I stopped by, is to try to pretend they’re not there. I witnessed so many families innocently play with the glacial ice, touching it to measure the chill. I saw children laugh and climb on top of the slick, wet blocks as their parents amusedly snapped photos. The end of the world, I left convinced, will at least look pretty on screen, set in Slumber or X-Pro II, with adequate fades and vignettes, then beamed into each of our pockets.

Aux grands hommes, la patrie reconnaissante, reads the rather pompous inscription on the frieze of the Panthéon: for great men, a grateful nation. When it was completed in 1790, in the early stages of the French Revolution, that motto was a promise for eternity. But today such promises — of the perpetuity of France, of the perpetuity of the planet — sound a little more dissonant. Like all those brilliant dead men and women entombed in the Panthéon, we watch helplessly as the ice leaks onto the cobblestoned street, and, somewhere far away, floods into the acidifying ocean. Of course, the grands hommes of our own time were in fact busying themselves this December with the COP21 climate conference, with which Ice Watch coincided and which ended with a binding international agreement intended to keep global temperature increases below two degrees Celsius. The Paris agreement, ratified a month after the attacks, is a landmark of diplomacy at least. But as the environmentalist Bill McKibben observed afterward, “In the hot, sodden mess that is our planet as 2015 drags to a close, the pact reached in Paris feels, in a lot of ways, like an ambitious agreement designed for about 1995, when the first conference of parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change took place in Berlin.”

Paris’s twin visions of apocalypse were on my mind when I stopped by the Louvre on a Sunday night before closing time. The usual hordes in front of the Mona Lisa were absent; museum attendance has been down since November 13. Downstairs, in the Hall Napoléon, was the wonderful and timely exhibition “A Brief History of the Future.” Inspired by a bestseller of the same name by Jacques Attali — a prolific writer, former adviser to François Mitterrand, and now big-ticket consultant — the show was a multidisciplinary juxtaposition of antiquities and artifacts, from the Louvre’s collection and elsewhere, with contributions from such contemporary artists as Wael Shawky, Camille Henrot, Ugo Rondinone, and Chéri Samba. The curators, Dominique de Font-Réaulx of the Louvre and Jean de Loisy of the Palais de Tokyo, laid out these works in fluid and open-ended fashion, though they coalesced around four themes: how the world is mapped and ordered, the rise and fall of empires, the history of exploration, and the “polycentric” world of today.

One of the achievements of “A Brief History of the Future” was to highlight the succession of historical moments of expansion and withdrawal—the permanence of our precariousness—and at this the show was deeply affecting. Early on, the mood was set by the Louvre’s copy of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1568 painting The Blind Leading the Blind, a depiction of the biblical parable. Six frightened figures, each with a different eye affliction, tilt their heads aloft and desperately hold on to each other as they fall in progression, like lemmings, into a ditch. Suspended against the darkened opposite wall were two of Tomás Saraceno’s transparent boxes containing enormous, gorgeous spider webs. If these intricate and massive constructions don’t resemble any we might encounter in nature, it’s because Saraceno periodically rotates the cube as the spiders work, altering their gravitational orientation in the process and creating something new and artificial. I struggled to understand the inclusion of these beautiful pieces until a bit of text further on noted that paradise, in the original sense of the word, simply meant “walled enclosure.” Which is the tragic and noble thread that ran through the show: we have never been able to resign ourselves to cease creating these paradises, no matter the cost.

All this evidence of our utter transience, as well as our tremendous and universal efforts to defy it, filled me somehow with an improbable hope. The sheer beauty of a strange and seemingly random collection of weapons, armor, helmets, and masks from Persian, Roman, and European empires felt both out of place and exactly right: the lengths we will go to defend our paradises cannot be discounted. Just beyond the arms and armor was Thomas Cole’s Course of Empire series, painted between 1833 and 1836, and far more shattering here than in its usual home at the New York Historical Society. Five large-scale paintings depict the growth and fall of an imaginary city, situated on the lower end of a river valley, where it meets an open bay. The valley is drastically altered but always identifiable in each of the canvases. Despite man’s fragility, the earth endures. Cole’s work draws directly from Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

’Tis but the same rehearsal of the past.

First Freedom, and then Glory — when that fails,

Wealth, vice, corruption — barbarism at last.

And History, with all her volumes vast,

Hath but one page...

Much further on, I paused in front of Martin Parr’s Ocean Dome (1996),a sobering depiction of mass recreation, which brings us all the way into the present. There is a crowd of sunbathers on an indoor artificial beach in Japan — the “summer” equivalent of fake ski resorts in Dubai. Somewhere deep down, there is the terrifying realization that such manmade beaches may soon be the only ones we have left, as the degradation of our real oceans and shorelines advances. It made me think of the soul-crushing images of men and women in Beijing last year, scurrying around in masks to protect themselves from the acrid air, watching the sunrise — invisible through the thick gray smog outside — on giant, government-supplied LED screens. The future is already here.

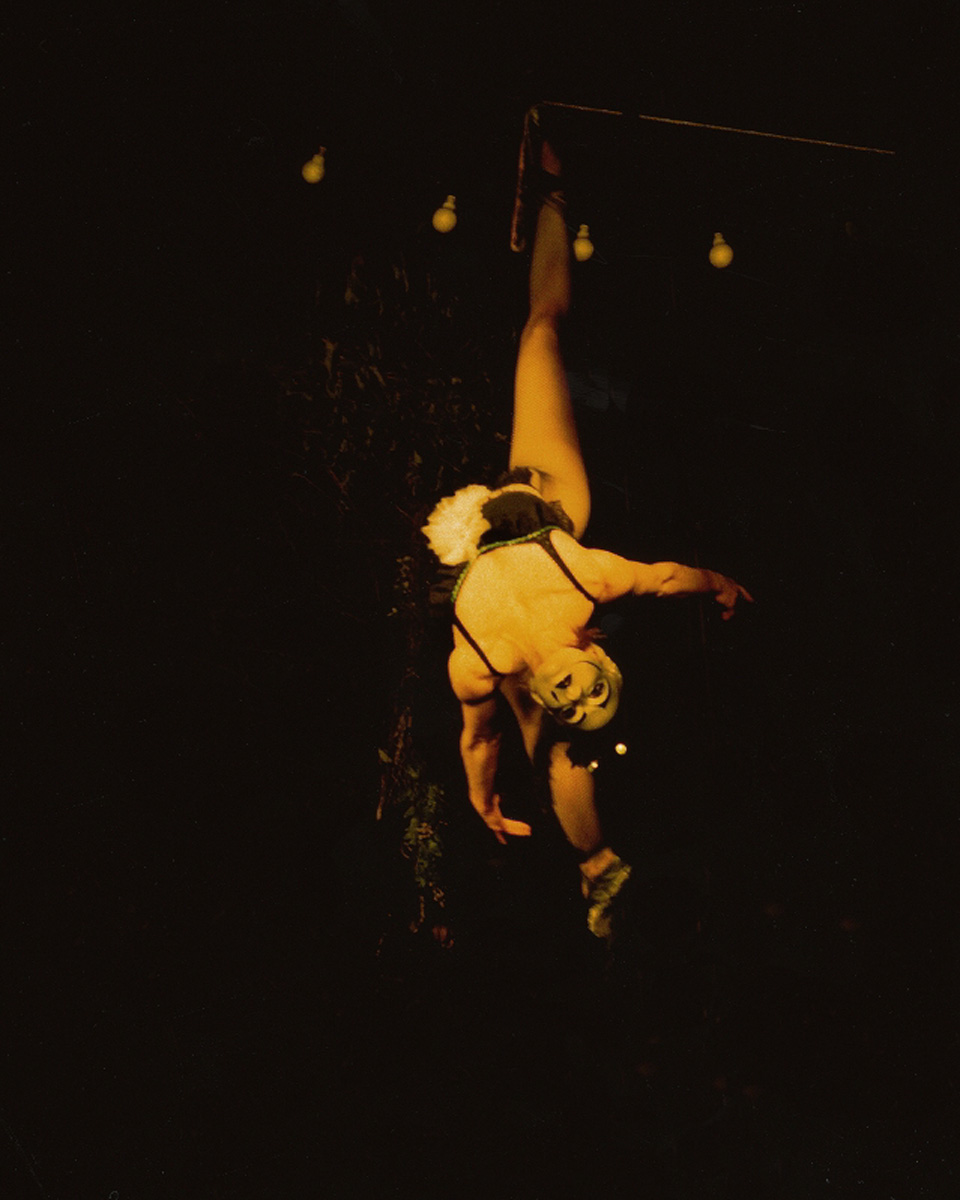

The show ramped up in its final phase, where one encountered a new work by Beijing’s own Ai Weiwei: Foundation, a grid of ground-down pillars constructed from centuries-old foundation stones. In the present context it served as a modern agora, as well as theater seating for a projection of a hyperactive film commissioned by the Louvre and drawing on Attali’s predictions of the future, complete with images of the collapsing World Trade Center. Indeed the destruction of the Twin Towers was literally manifest in the gallery, in the form of a twisted fragment of a Rodin bronze recovered from Ground Zero in the winter of 2001: a literal relic of terror and collapse. Ai’s work here is subtler, simultaneously evoking a lost empire and gesturing toward a new world to be built on top of existing foundations. And the show’s final image could hardly be more powerful in its ambivalence: Rhona Bitner’s miniscule photograph of an enigmatic acrobat, dangling upside-down by one sleek foot. She is, like all of us, in only partial control of her fate.

On the walk home, I scrolled through Instagram and noticed a friend’s three-year-old son perched on one of Ai’s smooth pillars, smiling at his mother, oblivious to the ruin around him. I must have just passed him. I found myself wondering how this boy, and how my own child, will grow up to think about the way we’ve acquitted ourselves in these tumultuous times. I would like to believe such works as I encountered in “A Brief History of the Future” will form part of their inheritance, but I am not sure. The day before I arrived back in Paris from Christmas in New York, a man had burst into the police headquarters not far from my home. He was wielding a knife, screaming “Allahu akbar,” and wearing what appeared to be a suicide vest (later revealed to be a phony). The police shot him dead.

My wife told me the news as soon as I got in. “That’s crazy,” I replied, but it was more of a reflex than a statement of genuine concern. The attacks feel so far away. Besides, I needed to go get groceries. The men with guns and hard faces guarding the synagogue on the street next to mine scrutinized me as I shuffled by, but I had already accustomed myself to their presence and went about my business.