Money Changes Everything

by Silas Martí

A conservator at Museu Oscar Niemeyer, Curitiba, unpacks artworks handed over by the Brazilian federal police. Photo: Kraw Penas. Courtesy Secretariat of Culture of the State of Paraná.

This is an excerpt from Even no. 3, published in spring 2016.

The Brazilian police investigation codenamed Operação Lava Jato (“Operation Car Wash”) began in 2014 as a probe into money laundering. They were going after black-market currency dealers; one woman was arrested with €200,000 in her underwear. But soon the investigation ballooned, and Lava Jato has since uncovered the biggest graft scandal in Brazilian history. An estimated $3 billion was diverted from Petrobras, the state-owned oil company, to the pockets of politicians from numerous parties. The chief of staff to former president Lula has been arrested. Police recently raided the home of the speaker of the lower house of Congress, who was found to have multiple Swiss bank accounts. The feds have seized weapons, jewelry, Ferraris, apartment buildings — and about 260 works of art. When the third and last cache of artworks repossessed from top executives and politicians arrived last year at the Oscar Niemeyer Museum in Curitiba, the hustle of armed policemen, television cameras, and blaring sirens underscored the unveiling of one painting or sculpture after another.

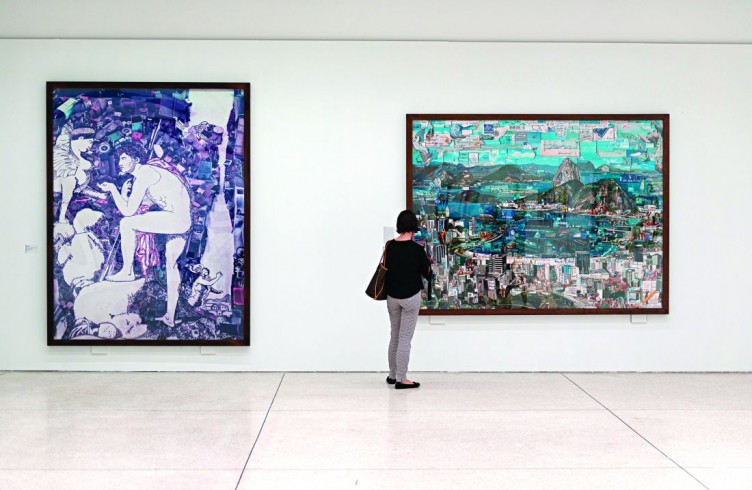

Corruption has become a sexy extravaganza in Brazil: live news broadcasts scour suspects’ every move, and the stock exchange tumbles downwards in real time with each new revelation. So perhaps it is understandable that this museum, off the beaten path for most Brazilian art lovers, drew nearly 200,000 visitors last year to “Works Under Guard,” which displayed 48 artworks confiscated from the living rooms of former directors of a public company. Gawking at modernist works by Cícero Dias, Di Cavalcanti, and Iberê Camargo, plus contemporary art by such market headliners as Vik Muniz and Miguel Rio Branco, museumgoers could ponder the works as twisted illustrations of the crumbling state of Brazilian affairs. For in the wake of the crisis, the real has lost over half its value against the dollar, unemployment has spiked, and Brazil’s president, Dilma Rousseff, now faces impeachment proceedings as the nation prepares itself to host this year’s Olympic Games in a mood far from festive.

I went to see the impounded artworks when I traveled to Curitiba this January. (Looking to linger in the spotlight a bit longer, the Niemeyer decided to restage last year’s presentation and also include several newly seized pieces, such as a Miró work on paper that caused a media uproar last year.) From a critical point of view, the juxtaposition of many B-list figurative painters, outsider art both good and mediocre, and gaudy contemporary fare — not to mention lesser pieces by Anna Maria Maiolino, Nelson Leirner, and Antonio Dias — seems rather random. Because it is. Maybe it’s best to think of it as yet another private collection show, of the sort proliferating in these times of hard-wired ostentation. “Works Under Guard” offers an uncompromising look at the taste, or lack of it, displayed by the country’s corrupt elite, and for good reasons and bad it is nothing short of spectacular.

The naïve depiction of a woman being courted by two musicians in Heitor dos Prazeres’s painting Roda de Samba, or Di Cavalcanti’s angular, cubist, and wildly colorful vision of what appears to be a Carnival ball, gains unexpected significance when seen in these circumstances. Below their cheerful surface, they are both works that hint at the very Brazilian tradition of drowning our sorrows in song and dance, and never looking a problem straight in the eye when things get ugly. If you saw the cover of the Economist’s first issue this year, you’ll know what I mean: it featured a grim portrait of the president staring downwards, foreseeing a disastrous 2016 for the nation.

What this exhibition of seized art reveals about Brazil seems to be the country’s natural talent for disguising mayhem, passing it off as a desirable and sultry combination of full-fledged hedonism and impulsiveness. In that regard, Vik Muniz’s photographic collage Rio de Janeiro — Cartão Postal seems to drive this point the furthest. It offers a clichéd vision of the now Olympic city’s dazzling Guanabara Bay made up of postcard cutouts, with nearly naked bodies sizzling on the sand and glimpses of dollar bills peeking from every crevice in the composition. I can only imagine some former director of Petrobras heading home from his office in downtown Rio and staring at this picture on the wall, its superficial beauty masking unreadable messages on the backs of those postcards sent abroad. Were all those travelers as infatuated with bling as these alleged criminals seem to have been?

It’s rather interesting that three of the seized works came from the great Brazilian modernist Cícero Dias. Before moving to Paris, the artist illustrated anthropologist Gilberto Freyre’s classic The Masters and the Slaves, which was published in 1933 and has since acquired cult status. It describes the atmosphere of “sexual intoxication” and “social plasticity” that marked the establishment of Brazil as a colony of Portugal in the 16th century, and it attempts to explain its modern-day propensity for corruption and wrongdoing, especially amongst the highest echelons of its power structure. Dias’s paintings in the show boast the same exuberance in color as his designs for Freyre’s book. They strike the same note as the works from Di Cavalcanti and Heitor dos Prazeres, for whom ignorance was utter bliss.

In a more subdued palette, mainly blacks and whites, a canvas by Daniel Senise that depicts an empty gallery sets off another alarm. Made with dust scraped off the floor of his studio, the artist’s highly praised paintings have always questioned the strange alchemy of the art world, whereby a piece of cloth may sometimes instantly acquire a six- to eight-digit price tag. Framed by this narrative of corruption and money laundering, this very painting that was used in a scheme of embezzlement sheds light on the complicity of the art market with the now not-so-secretive proceedings of the most powerful people in Brazil. Easier to trace than long-sold modernist pieces, the contemporary works on display here add an extra varnish of embarrassment and discomfort to an already very charged ordeal.

Postscript: On March 4, 2016, police officers in São Paulo raided the home of Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, the former president of Brazil, as part of Operação Lava Jato. He was released after three hours and was not charged with a crime.