Bagatelles

from Even No. 3, published spring 2016

Last summer, I spent a few hours talking to Ellsworth Kelly about his time in Paris: golden years, from 1948 to 1954, when the young artist rethought what a painting could be. He’d been in France during the war, but the Louvre was closed. He obtained an army scholarship to study at Beaux-Arts, but he never went to class; he worked for a time as a janitor in the office of the Marshall Plan, toured Byzantine churches, and painted. “It was the best time of my life, I guess,” Kelly told me. Everything that came after, the reliefs and the spectra, had been born under Paris’s gray skies.

Kelly’s was the last generation of Americans who saw Paris as capital of the arts; we appropriated that title soon enough. But in 2015 Paris became a new kind of world capital, for much grimmer reasons. The heinous murders of the staff of Charlie Hebdo, and the deficient, monolingual debates on freedom of expression that followed, were not the worst of it; come November, with an unfathomable assault on concertgoers and café patrons, Paris had become ground zero (a word we New Yorkers use advisedly) of a European and indeed global showdown around citizenship, freedom, and coexistence. Not a golden year; a year of cinders, a year of rust. But 2015 clarified something: Paris, too often misread as yesterday’s city, still plays its own giant part in shaping the future.

Even’s third issue revisits the birthplace of modern art, to see how Paris and its artists work in an anxious age. In the days after the attacks, during a UN climate conference we can fairly call historic, Thomas Chatterton Williams watched the city push forward, uneasy but unrelenting. The curator Guillaume Kientz got lost in the suddenly empty galleries of the Louvre; a refuge, it turns out, is not the same thing as an escape. Two young artists, Neïl Beloufa and Mathieu K. Abonnenc, take very different approaches to video and sculpture, yet both are obsessed with how France’s colonial history troubles its tripartite motto.

This issue also continues Even’s engagement with the place of music alongside visual art. Enough of Instagram; the real upheaval comes from Spotify, the latest in what Deirdre Loughridge shows is a centuries-long history of music technology entwining man and machine. And Daniel Fairfax, in an extensive monograph, places the artist Anri Sala in a media-spanning continuum in which first film, then music offer a method for art’s renewal. Sala left Albania for France in 1996; the art students come from elsewhere now, but they’re still coming, and the city has a grand curriculum. At Christmas I went to the Palais de Tokyo, passed through the metal detectors, and gazed through the tall window that Kelly, in the winter of 1950, translated into the most important work of his career. I mourned him and many others in Paris this year, but the city’s still here, the Paris Ellsworth made.

—Jason Farago, editor

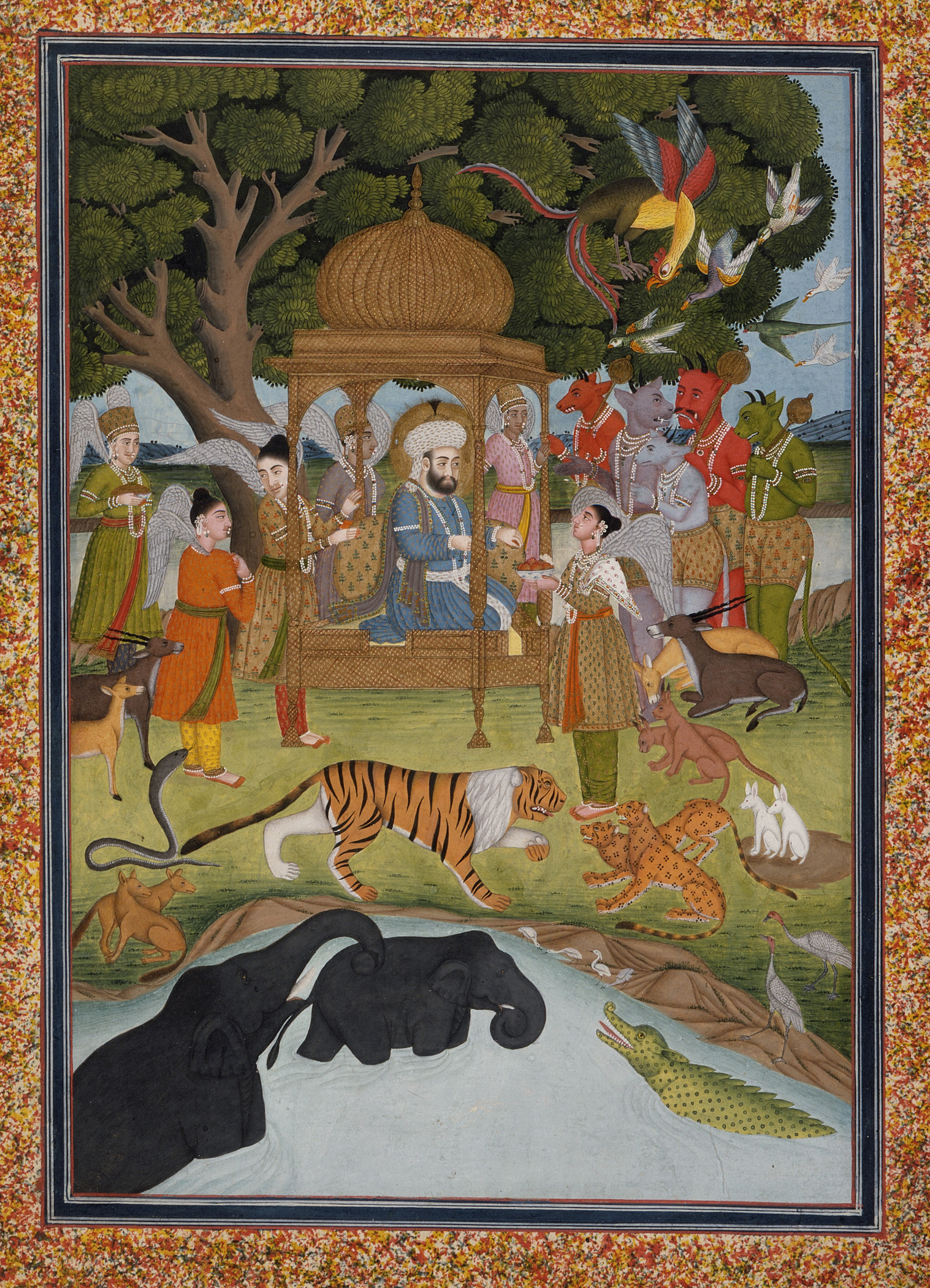

They’ve all come out to say good morning: rabbits and ibexes, birds scything through the branches, bathing elephants raising their trunks in homage. And on either side of the onion-domed litter, in which a turbaned monarch sits in virasana, are emissaries from far beyond Lucknow. Angels in red booties have arrived; so has a quintet of demons, outfitted for the day in floral swim trunks. The world is bounteous, but there are other worlds worth mentioning.

A king of Israel in a Mughal miniature, Solomon (or Sulayman) appears here as boss of three overlapping realms: the earth with its beasts and birds, the underworld home of the monsters at right, and the heavens too. He must have made a good model for an Indo-Islamic potentate. An epitome of justice, he also sits high enough on the leaderboard that any analogy must take the form of a partial disavowal. Leave to the Jewish king the two worlds above and below; the Mughal ruler can settle for this one.