Loudspeakers

by Daniel Fairfax

Anri Sala. No Barragán No Cry. 2002.

This is an excerpt from Even no. 3, published in spring 2016.

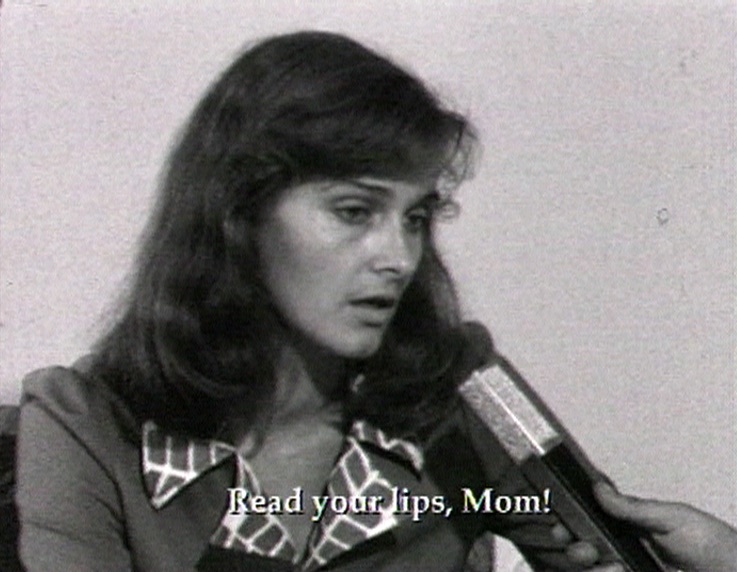

She’s captivating: a young woman with long, flowing hair, filmed in black-and-white, speaks with confidence into a microphone. The way she dresses, in a boxy pantsuit with a floral collar, along with the visual quality of the 16mm film stock, suggest that the footage has been taken sometime in the late 1970s. While holding forth for the interviewer she beams with pride — and with good reason. As the viewer of Anri Sala’s 27-minute experimental documentary Intervista (1998) has just seen, the woman has participated in one of her country’s major political events, the Congress of the Labour Youth Union of Albania. She has even had the rare privilege of standing shoulder to shoulder with Enver Hoxha, the Supreme Comrade, with the congress hall breaking out into one of the prolonged bouts of metronomic applause that were a regular feature of life under Stalinist regimes.

The woman in the footage is Anri Sala’s mother, Valdet. The soundtrack accompanying these images, however, is missing. Two decades after they were captured for Albanian state television, Sala transferred the 16mm reels to videotape. He screens them for his mother, who watches her 32-year-old self: a woman whose voice is muted, whose lips move but emit no sound. Transfixed by the images, anxiously laughing at what she sees, Valdet can only say in response, “Too bad the sound is lost.”

From this point, Intervista takes the form of a detective story. Sala is determined to locate the missing sound tapes. In succession, he telephones the journalist who questioned his mother, meets with the elderly former Central Committee member Todi Lubonja — expelled from the Party and imprisoned for 16 years after a falling out with Hoxha — and even tracks down the sound engineer for the interview. The sound engineer is now a taxi driver, and he relates that, at the time, sound and image were recorded and stored separately. The sought-after soundtrack for the footage of Sala’s mother has, most probably, been destroyed. All three figures attest to the paranoia and fear that impregnated Hoxha’s Albania. The reporter gruffly contends that “my questions were set in advance, as were the answers,” and even the lowly sound recorder was terrified of a technical incident occurring when party heavyweights were on camera.

Undeterred by the irrecoverable absence of the soundtrack, Sala hits upon a novel solution to his impasse: he visits a local school for the deaf, and he enlists lip-readers to “translate” the movements of his mother’s mouth into spoken language, which are then rendered as subtitles on the footage. Predictably enough, her interview turns out to have consisted of textbook phrases of Stalinist political jargon, a long stream of what semiotic theory would call empty signifiers: “This meeting was held,” the young Valdet explains, “to clearly express the political situation in the country in terms of the struggle against imperialism, revisionism, and the two superpowers, which is only possible with the Marxist-Leninist Party. And only if youth unites its efforts under the auspices of the Marxist-Leninist Party...”

The tape is paused. Having earlier been spellbound by the footage, the Valdet of 1998 is now in disbelief: “It’s absurd! I just can’t believe it! It’s just spouting words. There’s no sense to it. I know how to express myself.” Crucially, it is not the political content to which Valdet objects. It is the syntax of her discourse that truly disturbs her, the senseless cobbling together of set phrases into a near-indecipherable gibberish that she struggles to accept came from her own mouth.

An exploration of Albania’s political history, an interrogation of the roles of image, sound, and language in audiovisual media, and a touching sketch of the relationship between a mother and her son, Sala’s Intervista gained considerable renown for the first-time filmmaker, then aged 24. The film’s success — scooping up several festival awards and bringing Sala to the attention of critics across Europe — opened up the possibility for the artist to join the burgeoning field of documentary filmmaking. But while this foundational work established a reputation for what art historian Paolo Magagnoli calls Sala’s “enigmatic realism,” his subsequent output has proved to be of a particularly protean nature: initially concentrated in film and video art, Sala’s repertoire has expanded to incorporate sculpture, photography, and musical performance. Increasingly, too, the conditions of spectatorship have become integral to the Albanian artist’s œuvre, with his most recent works conceived specifically for multi-screen installations in the gallery space. Christine Macel, the curator for Sala’s 2012 show at the Centre Pompidou and 2013 presentation at the Venice Biennale, has referred to his “symphonic” juxtaposition of multiple video works in a single viewing environment, and this quality will surely come to the fore again in “Answer Me,” a retrospective at New York’s New Museum, which for the first time offers North American audiences an overview of the artist’s growing body of work.

Sala emerged in the European art scene of the late 1990s, at a time when a number of artists, from Pierre Huyghe and Stan Douglas to Doug Aitken and Douglas Gordon, were importing cinema into the white cube. Yet while his colleagues utilized cinema (often Hollywood cinema) as raw material for new works — a phenomenon the curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud baptized “postproduction” — Sala has shown no special interest in the cultural heritage of Hollywood, nor has he treated the media of celluloid and video as visual elements to be remixed or repurposed. Like peers such as Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Albert Serra, he is, strictly speaking, neither a filmmaker-cum-artist nor an artist-cum-filmmaker. Rather, Sala is equally at home in both spheres, to the point of liquidating any hard boundaries between the two. And while his more recent work has been shown exclusively in gallery settings — earning Sala the approbation of art historians and theorists such as Michael Fried, Jacques Rancière, and Boris Groys — a more specific concern for cinematic questions such as editing, mise-en-scène, and the sound-image nexus remains central to Sala’s art.

The intersection of cinema and visual art practices in Sala’s work can be traced back to his educational background. Trained at Tirana’s Academy of Fine Arts as a fresco painter soon after the end of Communist rule, Sala enrolled in the video department at France’s Le Fresnoy art school — almost by accident, as the artist himself tells it — and immersed himself in the work of auteur filmmakers such as Andrei Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, and Ingmar Bergman. It was in Paris that he made the acquaintance of Edi Rama, a fellow artist and expatriate Albanian. The two lived together for a time, but soon after Sala completed Intervista his friend returned to Albania and turned to politics, becoming mayor of Tirana in 2000. Rama’s signature policy was an urban regeneration program centered on painting the capital’s buildings in a panoply of bold colors. The result is a polychromatic cityscape that unwinds the cliché of the drab Eastern bloc metropolis, and instead resembles the Boca district of Buenos Aires, or even the red-saturated apartment in Godard’s La Chinoise (1967). In contrast to the stately charm of the Argentine capital or Haussmannian Paris, however, most of the edifices daubed under Rama’s administration are crumbling Brutalist monoliths connected by pothole-studded dirt roads, attesting to Tirana’s status as the capital of one of Europe’s poorest countries.

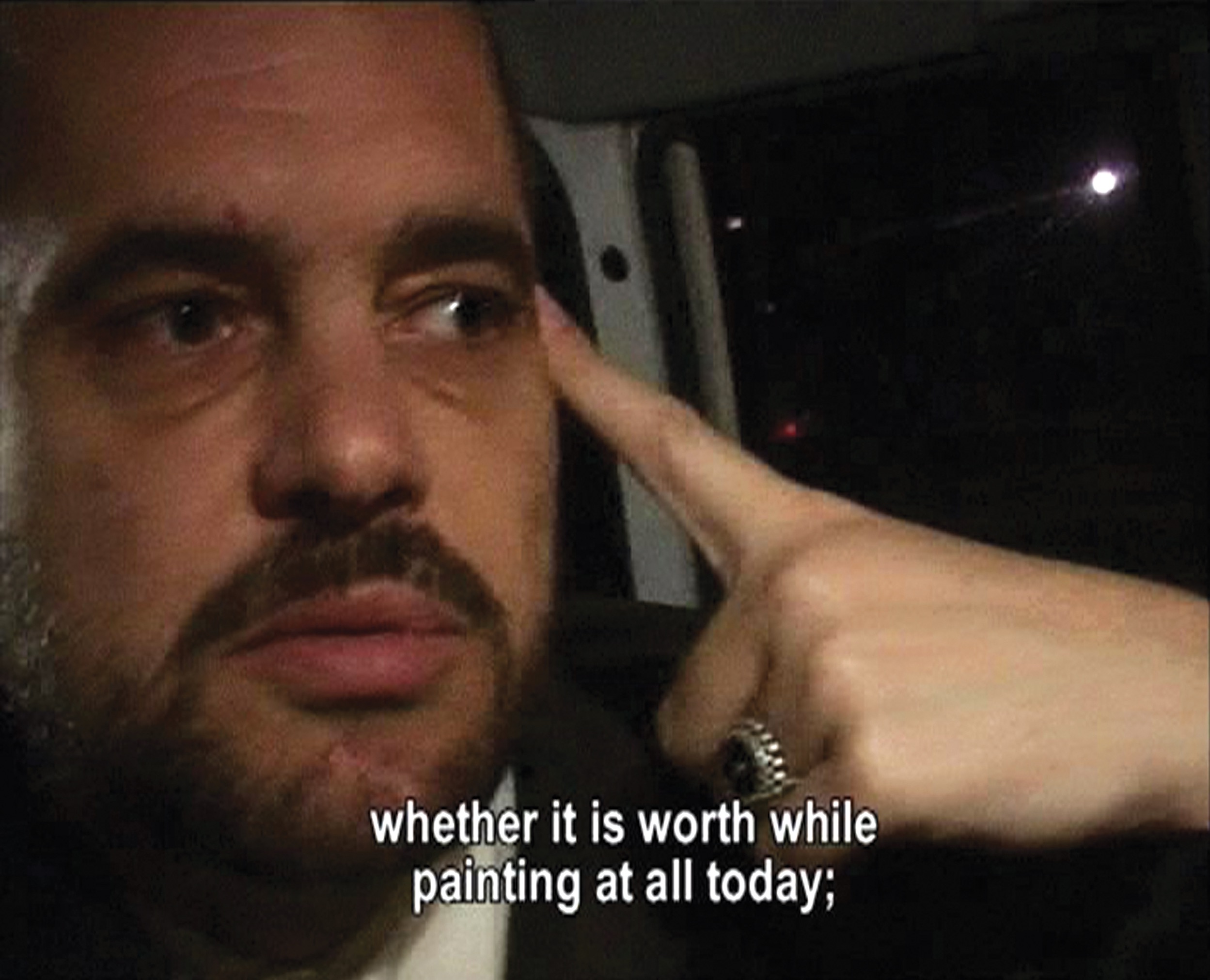

In Dammi i colori (2003), Sala’s camera prowls around these neighborhoods as they are transformed by municipal workers into the panels of a vast, abstract fresco. Long, nocturnal traveling shots taken from behind a car windshield show the brightly colored buildings illuminated by automobile headlights. In a dreamy voiceover accompanying the images, Rama muses, “Here, colors replace the organs, they are not part of the dress,” and insists that the colors displayed even have an impact on the breathing rhythms of city residents. The mayor observes that, as a result of his beautification project, “I do not think there is any other country in Europe where people discuss so passionately and collectively about colors.” Indeed, Rama’s transformation of the capital was hotly debated both within and beyond Albania: seen in some quarters as a quick and inexpensive way for decaying urban spaces to aesthetically remake themselves, it has been criticized in equal measure as a frivolous diversion from the city’s more pressing needs for social services and new infrastructure. Certainly, Sala does not flinch from contrasting the freshly painted walls of the apartment buildings with the squalor and decrepitude of modern-day Tirana. The residents that appear on camera, far from being enchanted by Rama’s paint job, just go about their daily business, blithely indifferent to the visual spectacle unfurling around them.

And yet the ebullient optimism of Rama’s vision does not leave us unmoved. Faced with these kaleidoscopic images of an otherwise nondescript city, the viewer will likely share the dazed incredulity of fellow artist Liam Gillick, who, according to the title card that opens the film, implored Sala: “Anri, tell me the truth. Tell me that this city does not exist. Please tell me that you do not have an artist-mayor friend.” Ostensibly, with the communist project’s political millenarianism eviscerated, only a modernist faith in abstract painting is left to provide a happier, more beautiful future. Indeed, whether consciously or not, the mayor of Tirana adopts a distinctly Leninist language when discussing the popularity of his aesthetic measures. The focus on spending a substantial portion of the municipal budget on a cosmetic makeover of the city is, he admits, “not an outcome of democratization, but more an avant-garde of democratization.” The choice and disposition of colors is a decision made from above, because, in Rama’s view, if such decisions were left to local residents the resulting “golden mean” would be nothing but a homogeneous gray. Rama even compares the relationship between a mayor and his electorate to that between artist and viewer — a statement that assumes a certain degree of passivity on the part of both the political citizenry and the artistic public.

Even with the political responsibilities of his position, Rama’s artistic sensibility is evidently irrepressible: late in the film he takes delight in the visual effect of the car’s red brake light set off against the blackness of the night. In pursuing an idiosyncratic dialogue between art and politics, Dammi i colori — the Italian title, which translates as “Give me the colors” is drawn from a line in Puccini’s Tosca, airs of which waft through the background of the film’s soundtrack — also demolishes stereotypes about the supposed backwardness of Albanian society. After the turmoil of the 1990s, the Balkan nation has largely avoided the authoritarian drift of many of its post-Communist neighbors. Instead, its populace elects a forward-thinking painter as mayor. A decade on from its release, Sala’s film has gained a fresh political context: Rama, the artist’s old Paris flatmate, is now prime minister of Albania, having been elected in 2013 on a platform promising progressive taxation, universal healthcare, and legal equality for gays and lesbians. Meanwhile, Rama’s artistic past has not been forgotten: the entrance to the prime ministerial office has a light-up awning by Philippe Parreno, and he gives press conferences in front of a Thomas Demand photograph.